To most Americans, citizenship, like DNA, seems like something a parent passes to a child without thought or effort. And indeed, for fathers around the world, that’s almost universally true.

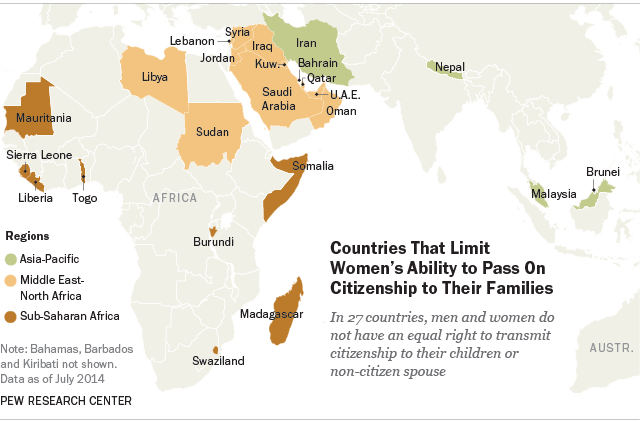

But one-in-seven countries currently have laws or policies prohibiting or limiting the rights of women to pass citizenship to a child or non-citizen spouse, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of data from the United Nations and the U.S. State Department. The U.N. data show these types of laws or policies were present in most countries around the world 60 years ago. In the past five years, multiple countries have taken steps to change these laws — including Kenya, Monaco, Yemen and Senegal. Just last month, Suriname changed its nationality laws to allow women to pass citizenship to spouses and children.

The United Nations tracks these laws as a part of its work to monitor stateless populations — particularly children who may become stateless if they cannot acquire nationality from either parent. Although in most situations a child can obtain nationality from his or her father, if the father is from a stateless population, the child may also be at risk to become stateless. As a result, these children and their stateless parent may be left without identity documents or access to education, health care or employment.

Some countries provide legal exceptions to allow children with stateless fathers to obtain citizenship from their mothers — including Jordan, Libya, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. However, some countries such as Qatar and Brunei do not have such policies in place.

Today there are 27 countries in which men and women do not have an equal right to pass citizenship to their children (or a non-citizen spouse). In contrast, men in these countries have virtually no barriers to pass citizenship to their non-citizen spouse and children. These restrictions are most prevalent in the Middle East and North Africa, where 12 out of 20 countries have such laws. In Jordan, for instance, the law prohibits women married to non-citizens from passing citizenship to their children.

In Jordan, 84,711 Jordanian women are married to non-citizens, and these families include about 338,000 children, according to a recent statement from the country’s Interior Ministry. In Saudi Arabia, women married to non-citizens are prohibited from transferring citizenship to their children, and, in addition, they are required to obtain government permission prior to marrying a non-citizen. Saudi men also require government permission if they want to marry a non-citizen from outside the Gulf Cooperation Council member states (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates).

Eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa include nationality laws or policies that limit women’s ability to pass citizenship to their children. While three of these countries — Burundi, Liberia and Togo — have “enshrined the principle of gender equality” in their constitutions, the pre-constitutional laws continue to be enforced, according to the U.N.

Five countries in the Asia-Pacific region and two in the Americas also have laws or policies limiting women in their ability to pass citizenship to their families. In the Bahamas, the law “makes it easier for men with foreign spouses than for women with foreign spouses to transmit citizenship to their children,” according to the State Department’s Human Rights Report. And in Kiribati — an island nation in the Pacific Ocean — non-citizen wives automatically are granted citizenship through their husbands, while I-Kiribati women who marry foreigners are not given that same benefit.

Sources for this data include the U.S. State Department’s annual report of Human Rights Practices, the United Nations’ annual background note on Gender Equality, Nationality Laws and Statelessness and through reference to official country-specific government websites. Download the data used in this analysis here.