By nature, Americans are an optimistic lot. Despite their resolutely negative opinion of economic conditions, majorities have consistently said that next year things will get better. Indeed, a Pew Research Center in-depth analysis in 2013 for the Council on Foreign Relations’ Renewing America initiative concluded that “despite the American people’s struggles with this extended period of economic difficulty, their core values and beliefs about economic opportunity, and the nation’s economic outlook, remain largely optimistic.”

By nature, Americans are an optimistic lot. Despite their resolutely negative opinion of economic conditions, majorities have consistently said that next year things will get better. Indeed, a Pew Research Center in-depth analysis in 2013 for the Council on Foreign Relations’ Renewing America initiative concluded that “despite the American people’s struggles with this extended period of economic difficulty, their core values and beliefs about economic opportunity, and the nation’s economic outlook, remain largely optimistic.”

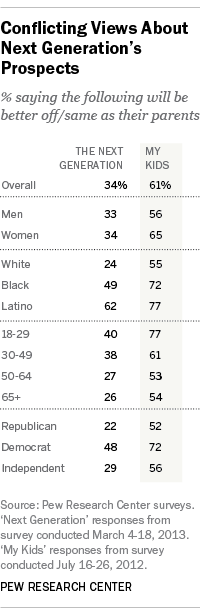

Yet, the public has somewhat conflicted views about the economic prospects for the next generation. When asked about the future prospects of “children today,” Americans generally said that when today’s kids grow up, they would be worse off financially than their parents. Nearly two-in-three respondents expressed that view in a Pew Research Center survey conducted in spring 2013. It is an opinion that was shared by rich and poor, young and old, men and women. Similar if not greater pessimism was also apparent in 10 of 13 advanced nations polled by Pew Research’s Global Attitudes Project.

While this is a pretty glum judgment about what lies ahead for today’s children, Americans’ optimism resurfaces when people are asked about their own kids. In 2012, despite the hard times of recent years, a plurality (42%) said that their own children will be better off, and an additional 19% say their children will be at least as well off as they are. Just 28% percent thought their own children will be worse off than they are when they reach adulthood. Less affluent segments of the public, including women, the less well-educated, Latinos and African Americans were particularly more likely to think that their children will be better off financially than they have been. There is a partisan divide as well, with more Democrats than Republicans, and in particular, Tea Party members, expecting their children to be better off than they have been.

However, when predictions about one’s children’s futures are compared with what people say about their own experiences, there are some indications of pessimism. As many as 58% say they are better off than were their parents at their age. But just about half of this group (30%) say their own children will match them in doing better than their parents, while about as many (28%) do not say their own children will top them.

Young Americans, blacks, Latinos and Democrats more often than their demographic counterparts say both that they are better off than their parents and that their own children will be even better off. Whites, Republicans and especially members of the Tea Party say less often than average that they are better off than their parents and that their own children will top them.

On balance it seems that the closer one gets to home, the more positive people are about their children’s prospects. The country’s kids will not do so well, but my own kids will at least match me or do better. One qualifier is that a sizable number of Americans, who have done better than their own parents, don’t see their own children topping them.

Somewhat muted optimism about one’s children’s prospects, and all out pessimism about the “next generation” more generally, may be explained in part by the fact that people in advanced nations, such as the U.S., Germany and Great Britain, are less likely to see prospects for economic growth than the publics of emerging economies such as China, Brazil, Chile and Malaysia, where there is great optimism about the next generation.