Millions of Americans counted in the 2000 census changed their race or Hispanic-origin categories when they filled out their 2010 census forms, according to new research presented at the annual Population Association of America meeting last week. Hispanics, Americans of mixed race, American Indians and Pacific Islanders were among those most likely to check different boxes from one census to the next.

Millions of Americans counted in the 2000 census changed their race or Hispanic-origin categories when they filled out their 2010 census forms, according to new research presented at the annual Population Association of America meeting last week. Hispanics, Americans of mixed race, American Indians and Pacific Islanders were among those most likely to check different boxes from one census to the next.

The researchers, who included university and government population scientists, analyzed census forms for 168 million Americans, and found that more than 10 million of them checked different race or Hispanic-origin boxes in the 2010 census than they had in the 2000 count. Smaller-scale studies have shown that people sometimes change the way they describe their race or Hispanic identity, but the new research is the first to use data from the census of all Americans to look at how these selections may vary on a wide scale.

“Do Americans change their race? Yes, millions do,” said study co-author Carolyn A. Liebler, a University of Minnesota sociologist who worked with Census Bureau researchers. “And this varies by group.”

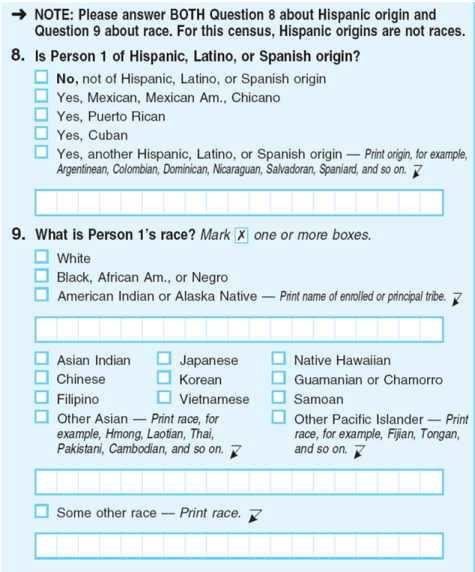

Why? There are many possibilities, although the researchers did not present any hard conclusions. By some measures, the data provide more evidence of Americans’ puzzlement about how the census asks separately about race and ethnicity. (The Census Bureau is considering revising its race and ethnicity questions for the next census, in 2020, in hopes of matching better how Americans think about this topic.) But there could be other reasons, too, such as evolving self-identity or benefits associated with being identified with some groups.

The Census Bureau granted the researchers restricted access to confidential data in return for a legally binding promise that they would not reveal details of any individual responses, and they produced their estimates by matching 2000 and 2010 census forms for the same people. Though they were able to analyze data for more than half the U.S population (and most of the 281 million counted in 2000), the amount of category-changing might be even higher in the total population, they said.

People of every race or ethnicity group altered their categories on the census form, but some groups had more turnover than others. Relatively few people who called themselves non-Hispanic white, black or Asian in 2000 changed their category in 2010, Liebler said. Responses by Hispanics dominated the total change, she said, but there was major turnover within some smaller race groups as well.

The largest number of those who changed their race/ethnicity category were 2.5 million Americans who said they were Hispanic and “some other race” in 2000, but a decade later, told the census they were Hispanic and white, preliminary data showed. Another 1.3 million people made the switch in the other direction. Other large groups of category-changers were more than a million Americans who switched from non-Hispanic white to Hispanic white, or the other way around.

Hispanics account for most of the growing number and share of Americans who check “some other race” on the census form. Many do not identify with a specific racial group or think of Hispanic as a race, even though it is an ethnicity in the federal statistical system. Census officials added new instructions on the 2010 census form stating that Hispanic ethnicity is not a race in an attempt to persuade people to choose a specific group. (That change, as well as other wording edits in the instructions to respondents between 2000 and 2010 may be one reason some people switched. The order of the questions and the offered categories did not change.) The Census Bureau is also testing a new race and Hispanic question that combines all the options in one place, rather than asking separately about race and Hispanic origin.

More than 775,000 switched in one direction or the other between white and American Indian or only white, according to preliminary data. A separate paper presented at the conference reported “remarkable turnover” from 2000 to 2010 among those describing themselves as American Indian. Ever since 1960, the number of American Indians has risen more rapidly than could be accounted for by births or immigration.

There also was considerable change within a decade’s time among some smaller race groups. For example, only one-third of Americans who checked more than one race in 2000 kept the same categories in 2010, according to preliminary data. Only two-thirds of non-Hispanic single-race Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders kept the same categories.

Previous research on people’s racial self-identification has found that they may change categories for many reasons, said demographer Sharon Lee of the University of Victoria in Canada, at the population conference. The question mode—whether people are asked in person, on a paper form, on the phone or online—makes a difference. Some people may change their category after they find out they had an ancestor of a different race, she said. Or they may decide there are benefits (such as priority in college admissions) to including themselves in a certain group.

Some category-changers were children in 2000 whose race was filled in by their parents, but by 2010 were old enough to choose for themselves, which may account for some of the change. Children in some groups in 2000—for example, white and black—were especially likely to be recorded in a different category in 2010, Liebler said. (Although she did not mention President Barack Obama, he chose to check only “black” on his 2010 census form, even though his mother was white and father black.)

Lee and Liebler said researchers need to account for the amount of change in people’s racial and Hispanic self-description in their work, but Lee cautioned that they should not overreact. “There is not a trivial amount of change,” she said, “but it’s not across every group.”

The analysis was done under a Census Bureau program to allow limited access to its confidential data for specific studies of important issues by outside researchers who agree not to reveal any personally identifying information about individuals. In this case, researchers did not have access to individual names, dates of birth or other personal information, because each person’s linked 2000 and 2010 forms were identified by a numerical code called a “personal identification key.”

The researchers only included in their analysis people living in households where someone in the family filled in their race or Hispanic origin. They excluded people whose details were supplied by neighbors or imputed by the Census Bureau, and those living in group quarters, such as college dormitories or prisons. They also dropped anyone who checked “some other race” and an additional race in 2000, because that category had an unusual amount of processing error. The researchers said the people they matched were not nationally representative.