Former Chongqing Communist Party boss Bo Xilai was given a life sentence yesterday, ending China’s most high profile political trial in decades. With plot lines involving bribery, adultery, and murder, the courtroom drama drew considerable attention in China and around the world. The Financial Times called it “the OJ Simpson trial and the life of Paris Hilton rolled into one.”

Former Chongqing Communist Party boss Bo Xilai was given a life sentence yesterday, ending China’s most high profile political trial in decades. With plot lines involving bribery, adultery, and murder, the courtroom drama drew considerable attention in China and around the world. The Financial Times called it “the OJ Simpson trial and the life of Paris Hilton rolled into one.”

The case of Bo Xilai highlights an increasing central issue in Chinese politics: political corruption.

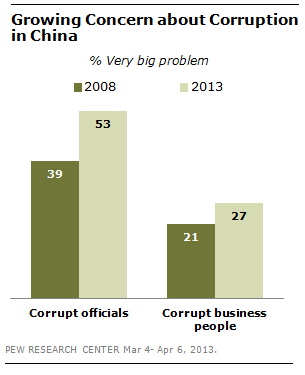

Since taking office earlier this year, Chinese President Xi Jinping has emphasized the need to crackdown on corruption, promising to pursue both high-level and low-level officials (“tigers” and “flies”). Among the country’s average citizens, corruption is a growing concern. Fully 84% described political corruption as a big problem in a spring 2013 Pew Research Center survey of China. More than half (53%) said it was a very big problem, up from 39% five years ago. Among the 17 issues included on the survey, only inflation (59% very big problem) was rated as a bigger concern.

Many of the charges facing Bo revolved around the close financial ties between his family and elements of the business community – ties that the Bo clan used to support a lavish lifestyle. He may have gained notoriety for promoting socialist themed “red songs” (“Love of the Red Flag” was apparently a favorite) and populist rhetoric, but Bo’s tastes were not especially proletarian. For example, his family acquired a $3.2 million French villa with some financial help from Chinese plastics mogul Xu Ming.

Increasingly, the Chinese public sees corruption in the business world, as well as the political realm. Roughly seven-in-ten (71%) said corrupt business people are a big problem, with 27% saying they are a very big problem, up slightly from 21% in 2008.

China has experienced extraordinary economic growth in recent years, and the Chinese are more satisfied with the direction their country than most other publics we’ve surveyed around the world, but as our polling also illustrates, the Chinese public is growing frustrated with both its political and business elites, many of whom, like Bo, are enjoying more than their share of the country’s newfound riches.