The presidency may well be a “bully pulpit,” in Theodore Roosevelt’s original sense, a position that commands attention. But as President Barack Obama prepares to address the nation Tuesday in support of taking military action against Syria, there’s little evidence (at least in recent times) that presidential speeches are very effective at moving the needle on public opinion or rallying popular support against a balky Congress.

We searched a database of major presidential addresses maintained by the American Presidency Project at the University of California-Santa Barbara, picking out ones where the president talked about a specific issue pending before Congress and asked for the public’s support. Then, we searched through decades of survey research (our own and others’) to try to assess what impact, if any, the speeches had. That, frankly, was more difficult than we thought — it turns out news organizations and research organizations seldom asked about the same issue in exactly the same way over a relatively short time (roughly a month before and a month after the speech in question).

Still, we found enough cases to conclude that the speeches don’t seem to do much to move the needle on public opinion or push Congress in the president’s direction. President Ronald Reagan, for instance, was unable to convince even a plurality of Americans that the United States should provide military aid to the Contra rebels fighting Nicaragua’s Sandinista government, despite three Oval Office addresses on the issue between March 1986 and February 1988.

In October 1990, as Congress prepared to vote on a deficit-reduction deal reached between congressional leaders and President George H.W. Bush, he went on the air to defend the deal and urge its passage. A few weeks before the speech, only a third of people in an ABC News/Washington Post poll had supported the deal. Afterward, a Times Mirror survey found an almost identical percentage in favor of the plan, though 24% said they didn’t know or were undecided (versus 3% in the earlier poll).

More recently, in May 2006, President George W. Bush spoke to the nation urging passage of a plan that included a “path to citizenship” for unlawful immigrants, along with increased border enforcement. A Pew Research Center survey conducted a month later found 56% support for such a plan — almost exactly the percentage who said they supported a path to citizenship a month before the president’s speech.

Support for President Clinton’s economic-recovery plan was tepid both before and after his August 1993 televised address. Opinion did change somewhat before and after Clinton’s June 1995 speech on that year’s budget standoff with congressional Republicans, though perhaps not in the way he’d hoped: Before the speech, according to a Gallup/CNN/USA Today poll, support was about equally divided between Clinton’s plan and the GOP approach; afterward, a Time/CNN poll found 39% support for Clinton’s plan, 19% for the GOP plan, and 39% saying they didn’t like either.

George C. Edwards III, founding director of Texas A&M University’s Center for Presidential Studies, did a more systematic study along these lines several years back. His conclusion was pretty well summed up in the title of his 2006 book, “On Deaf Ears: The Limits of the Bully Pulpit“: Even “Great Communicator” presidents such as Reagan and FDR have been far less effective at changing people’s minds through rhetoric than we — and they — imagine.

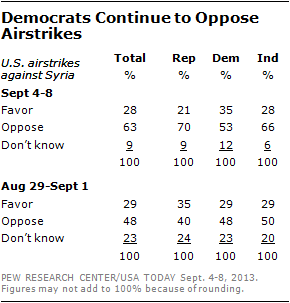

Indeed, as Ezra Klein wrote in The New Yorker last year, sometimes high-profile presidential speeches can actually impede governance, by turning an issue into a partisan test of strength. Obama may be experiencing that phenomenon now as regards Syria. Even before his speech, Pew Research’s latest survey found public support has been falling for the White House’s plan to take action against Syria. And Republican opposition in particular has surged from 40% to 70% in the space of a week.

Indeed, as Ezra Klein wrote in The New Yorker last year, sometimes high-profile presidential speeches can actually impede governance, by turning an issue into a partisan test of strength. Obama may be experiencing that phenomenon now as regards Syria. Even before his speech, Pew Research’s latest survey found public support has been falling for the White House’s plan to take action against Syria. And Republican opposition in particular has surged from 40% to 70% in the space of a week.