Are men losing interest in work?

Male labor force participation rates in the United States have been in steady decline since at least 1950 while women’s labor market participation steadily rose before leveling off about a decade ago. Two recent analyses of U.S. Census data document this trend and offer some unexpected reasons why this shift is occurring.

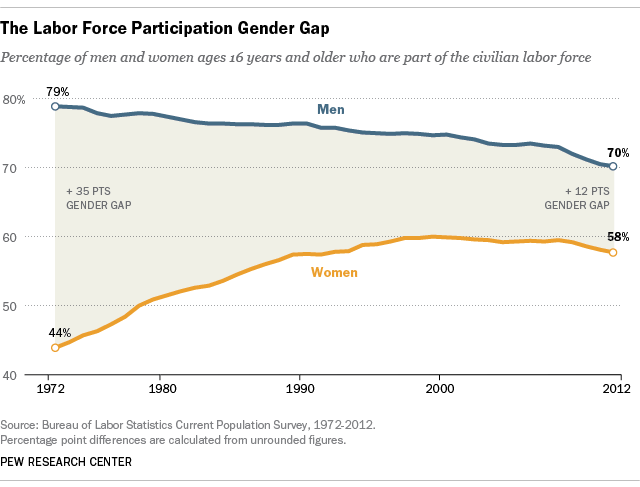

Economists Stefania Albanesi and Ayşegül Şahin of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York analyzed U.S. Census data extending back four decades. They found the labor force participation gap between men and women has closed dramatically since 1970 when only 43% of women but 80% of men 16 years and older were employed or looking for work.

The gap stood at about 12 percentage points (57.7% vs. 70.2%) in 2012 and is projected to narrow slightly over the next few decades as participation rates for both sexes slowly decline.

“Women have become less likely to leave employment for nonparticipation—a sign of increased labor force attachment—while men have become more likely to leave the labor force from unemployment and less likely to re-enter the labor force once they leave it—a sign of decreased labor force attachment,” Albanesi and Şahin wrote in a recently released working paper.

Translation: Women are less likely than they were in the past to leave a job and drop out of the labor force to raise a family, take care of aging parents or family members, or for other reasons. Men, on the other hand, are increasingly more likely to quit, be laid off or fired, or otherwise leave a job and opt not to look for another.

But why are men having an increasingly hard time entering or staying in the labor market–and why are some dropping out entirely?

MIT economists David Autor and Melanie Wasserman think they know one of the reasons why. In a recent study for the Third Way think tank they found that men are falling behind women in acquiring necessary job skills—primarily high school and college degrees—and it’s showing in the inferior kinds of work they get, the lower wages they are paid and in their diminished chances of finding and keeping a job. Little wonder guys are discouraged.

“Over the last three decades the labor market trajectory of males in the U.S. has turned downward along four dimensions: skills acquisition; employment rates; occupational stature; and real wage levels,” Autor and Wasserman write.

These researchers acknowledge that scholars don’t yet know all of the causes of these changes. They suggest globalization, the diminishing power of labor unions and the dizzying pace of technological change all may pose barriers to stable employment and raise frustration levels, particularly among men. Other scholars have cited institutional changes that have made it easier for mothers to work. Changes in family structure, immigration and the aging of the Baby Boom generation also may contribute to these trends. Add to that the simple fact that men—particularly those with a working wife—don’t need to work as long or as hard these days to support a family, or to even work at all.

To this long and growing list Autor and Wasserman add another intriguing possibility: Absentee dads.

Sifting through Census data, they find a significant share of this shift in employment outcomes is largely occurring in one group: men born into single-parent households, most of which are headed by women. As a group, these boys are significantly less likely to graduate from high school or go to college than other children, they found.

Even girls raised by a single parent fare better in later life than a boy who grew up in similar circumstances, even though both suffered from lower incomes, less advantageous school and neighborhood environments and higher stress levels than other children.

But they add that “boys in single female-headed families are particularly at risk for adverse outcomes across many domains, including high school dropout, criminality and violence,” also noting that “male parental absence may appear to differentially disadvantage boys because boys are more sensitive than girls to either male role models or these other forces.”