While the Senate appears to have reached a deal on executive-branch appointments that heads off a showdown over filibuster rules, the fact that the confrontation went as far as it did points up the increasingly polarized state of Congress. From immigration reform to food stamps to student loans, it almost seems as if congressional Republicans and Democrats inhabit different worlds.

In a way, they do. Not only are Republicans and Democrats elected from very different districts with distinct voter bases, but Congress reflects an America that has been growing further and further apart ideologically for decades.

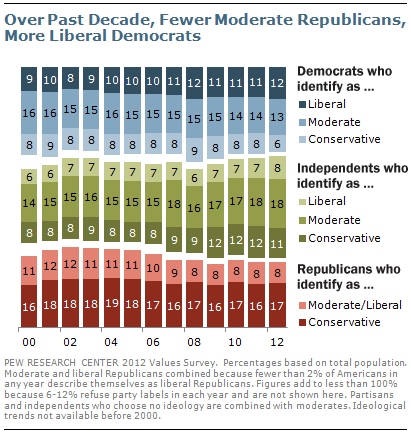

Start with the voters. For years the Pew Research Center has asked people which party, if any, they identify with and whether they describe their political views as conservative, moderate or liberal. Put those results together and you get a portrait of polarization; it clearly shows that self-described conservatives make up a greater share of Republicans in 2012 (68%) than they did in 2000 (59%), while self-described liberals account for a greater share of Democrats (27% in 2000, 39% in 2012). (There are considerably more independents — 37% of respondents picked that label in 2012 versus 28% in 2000 — but the proportions of liberals, moderates and conservatives within the independent group have stayed roughly the same.)

Start with the voters. For years the Pew Research Center has asked people which party, if any, they identify with and whether they describe their political views as conservative, moderate or liberal. Put those results together and you get a portrait of polarization; it clearly shows that self-described conservatives make up a greater share of Republicans in 2012 (68%) than they did in 2000 (59%), while self-described liberals account for a greater share of Democrats (27% in 2000, 39% in 2012). (There are considerably more independents — 37% of respondents picked that label in 2012 versus 28% in 2000 — but the proportions of liberals, moderates and conservatives within the independent group have stayed roughly the same.)

Those self-identifications reflect real and deepening divisions on a host of issues, the Pew Research report concluded: “Across 48 different questions covering values about government, foreign policy, social and economic issues and other realms, the average difference between the opinions of Republicans and Democrats now stands at 18 percentage points…nearly twice the size of the gap in surveys conducted from 1987-2002.”

In addition, as The New York Times illustrated recently, red and blue America have very different racial and ethnic makeups. House districts represented by Democrats are collectively just over half white, 16% black and nearly a quarter (22.5%) Hispanic; Republican-represented districts are nearly three-quarters white, 8.5% black and 11.1% Hispanic.

That’s in part because most House districts have been carefully drawn to be as “safe” for Republicans or Democrats as legally possible. Last year, 30 out of 435 House elections were decided by less than 5 percentage points, while 69 percent of incumbents running for re-election won with more than 60% of the vote. The Rothenberg Political Report currently lists just 47 House seats as “in play” for next year’s election; exclude the races where Democrats or Republicans are favored to win, and you’re down to 29.

The overall result: Most representatives are elected from districts dominated by a single party, whose adherents have themselves grown less moderate over time. Given that, it’s hardly surprising that the congressional parties are growing further and further apart ideologically, as depicted in the two charts to the right. They’re derived from data in the newly released “Vital Statistics on Congress” compendium, a joint effort between two longtime and well-respected scholars of Congress, Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute and Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution. (If you want to know how many Jewish Republicans there were in the House in 1967 or when the first Hispanic was elected to the Senate, this is the place to go.)

Given that, it’s hardly surprising that the congressional parties are growing further and further apart ideologically, as depicted in the two charts to the right. They’re derived from data in the newly released “Vital Statistics on Congress” compendium, a joint effort between two longtime and well-respected scholars of Congress, Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute and Thomas Mann of the Brookings Institution. (If you want to know how many Jewish Republicans there were in the House in 1967 or when the first Hispanic was elected to the Senate, this is the place to go.)

Ornstein and Mann list the average ideological positions of House and Senate Republicans and Democrats in each Congress since the end of World War II, adopting a scoring procedure developed some three decades ago by Keith Poole of the University of Georgia and Howard Rosenthal of NYU. The Poole-Rosenthal scale, based on members’ voting records, runs from -1 (most liberal) to +1 (most conservative).

Poole himself, in an article in UGA Research magazine (pages 34-35) discusses their methodology (including breakouts of Southern and non-Southern Democrats, not shown here) and draws some rather grim conclusions: “With almost no true moderates left in the House of Representatives, and just a handful remaining in the Senate, bipartisan agreements to fix the budgetary problems of the country are now almost impossible to reach. [And] given that trends in polarization have continued unabated for decades and appear to be related to underlying structural economic and social factors…it is unlikely that this deadlock will be broken anytime soon.”