Gene editing giving babies much reduced risk of serious disease

Respondents to the Pew Research Center survey read the following statement: “New developments in genetics and gene-editing techniques are making it possible to treat some diseases and conditions by modifying a person’s genes. In the future, gene-editing techniques could be used for any newborn, by changing the DNA of the embryo before it is born, and giving that baby a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions over his or her lifetime. Any changes to a baby’s genetic makeup could be passed on to future generations if they later have children, and over the long term this could change the genetic characteristics of the population.”

The potential genetic modification of humans and its ramifications have long been debated, but a recent scientific breakthrough in gene editing – a technique known as CRISPR – has raised the urgency of this conversation. In March and April of 2015, two separate groups of scientists published essays urging the scientific community to impose limits on genomic engineering, and the National Academies of Sciences, working in cooperation with the United Kingdom’s Royal Society and the Chinese Academy of Sciences, convened an international summit to discuss the science and policy of human gene editing. (For more details on these developments, see “Human Enhancement: The Scientific and Ethical Dimensions of Striving for Perfection.”)

The Pew Research Center survey gauged, in broad terms, what the public thinks about the potential use of gene editing to enhance people’s health, in this case by reducing the probability of disease over a person’s lifetime.11 Survey respondents were asked to consider a potential future scenario, republished in the accompanying sidebar, in which gene editing would be used to give healthy babies a much reduced risk of developing serious diseases. Gene-editing techniques are not currently being used in this way.

While many Americans say they would want to use such a technology for their own children, there is also considerable wariness when it comes to gene editing, especially among parents of minor children. Highly religious Americans are much more likely than those who are less religious to say they would not want to use gene-editing technology in their families. And, when asked about the possibility of using human embryos in the development of gene-editing techniques, a majority of adults – and two-thirds of those with high religious commitment– say this would make gene editing less acceptable to them.

This chapter focuses on these patterns and several others involving public attitudes about gene editing.

Despite some enthusiasm, the American public is largely wary about gene editing for babies

Americans have mixed emotional reactions to the possibility of using gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of serious diseases, although more people express concern rather than enthusiasm. Fully two-thirds of U.S. adults (68%) say the prospect makes them either “very” or “somewhat” worried, while roughly half (49%) say they are “very” or “somewhat” enthusiastic about this technology. Three-in-ten adults are both enthusiastic and worried.

Americans have mixed emotional reactions to the possibility of using gene editing to reduce a baby’s risk of serious diseases, although more people express concern rather than enthusiasm. Fully two-thirds of U.S. adults (68%) say the prospect makes them either “very” or “somewhat” worried, while roughly half (49%) say they are “very” or “somewhat” enthusiastic about this technology. Three-in-ten adults are both enthusiastic and worried.

Asked to consider whether they would want this kind of gene editing for their own baby, Americans are split, with 48% saying they would want to use this technology for their child and a nearly identical share saying they would not. Parents who currently have a child under age 18 are less inclined than others to say they would want this kind of gene editing for their own baby; a clear majority of these parents (59%) would not want to use gene editing for their child.

Asked to consider whether they would want this kind of gene editing for their own baby, Americans are split, with 48% saying they would want to use this technology for their child and a nearly identical share saying they would not. Parents who currently have a child under age 18 are less inclined than others to say they would want this kind of gene editing for their own baby; a clear majority of these parents (59%) would not want to use gene editing for their child.

Respondents also were asked whether they think “most people” would want to use gene-editing technology. Overall, a slim majority of Americans (55%) expect most people would want this kind of gene editing for their baby, while 42% say most people would not want this.

Those familiar with gene editing more inclined to want it for their own baby

Those familiar with gene editing more inclined to want it for their own baby

Ideas about genetic modification and the potential for “designer babies” have been discussed among scientists, bioethicists and the broader public for some time.

When asked about their familiarity with gene editing, most Americans say they have heard either a little (48%) or a lot (9%) about this idea before, although a substantial minority (42%) had not heard anything about the possibility of gene editing before taking the survey.

When asked about their familiarity with gene editing, most Americans say they have heard either a little (48%) or a lot (9%) about this idea before, although a substantial minority (42%) had not heard anything about the possibility of gene editing before taking the survey.

Those who are at least somewhat familiar with the idea of gene editing are more inclined to say it is something they would want for their baby to reduce the child’s lifelong risk of certain serious diseases and conditions. Among those who have heard or read “a lot” or “a little” about gene-editing technology, 57% say they would want it for their child. But among those who had heard nothing at all prior to the survey, only 37% feel the same way.12

Strong religious divides in preferences about gene editing

Personal preferences about gene editing are strongly tied to differences in religious commitment and affiliation.

Respondents were classified into high, medium and low levels of religious commitment based on the self-described importance of religion in their lives, frequency of worship service attendance and frequency of prayer. A person who says religion is very important in their life and who says they attend religious services at least weekly and pray at least daily is considered to have a “high” level of religious commitment, while a person who says religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their life and who seldom or never attends religious services or prays is placed in the “low” commitment category. All others are classified as having “medium” commitment.

Respondents were classified into high, medium and low levels of religious commitment based on the self-described importance of religion in their lives, frequency of worship service attendance and frequency of prayer. A person who says religion is very important in their life and who says they attend religious services at least weekly and pray at least daily is considered to have a “high” level of religious commitment, while a person who says religion is “not too” or “not at all” important in their life and who seldom or never attends religious services or prays is placed in the “low” commitment category. All others are classified as having “medium” commitment.

A majority of people with high religious commitment (64%) say they would not want gene editing for their own baby. By contrast, a nearly identical share of Americans with low religious commitment say they would want to use the technology for their child. Americans with a medium level of religious commitment are closely divided, with 48% saying they would want gene editing for their baby and 50% saying they would not.

A majority of people with high religious commitment (64%) say they would not want gene editing for their own baby. By contrast, a nearly identical share of Americans with low religious commitment say they would want to use the technology for their child. Americans with a medium level of religious commitment are closely divided, with 48% saying they would want gene editing for their baby and 50% saying they would not.

There also are wide differences in feelings about gene editing by religious affiliation. White evangelical Protestants, who tend to be highly religious compared with other groups, are among the least likely to want their baby to have gene editing to reduce the risk of certain serious diseases (61% would not want it).

By contrast, majorities of atheists (75%) and agnostics (67%) would want to use gene editing for this purpose. Those who say their religion is “nothing in particular” are closely divided on this question, as are Catholics (both white and Hispanic) and white mainline Protestants.

Americans closely split on whether gene editing crosses a line that should not be crossed

The survey asked respondents whether the idea of editing genes to give healthy babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions is in keeping with other ways that humans have always tried to better themselves or whether “this idea is meddling with nature and crosses a line we should not cross.” Americans’ judgments on this question are closely divided, with 51% saying this idea is no different than other ways humans try to better themselves and 46% saying this idea crosses a line.

The survey asked respondents whether the idea of editing genes to give healthy babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions is in keeping with other ways that humans have always tried to better themselves or whether “this idea is meddling with nature and crosses a line we should not cross.” Americans’ judgments on this question are closely divided, with 51% saying this idea is no different than other ways humans try to better themselves and 46% saying this idea crosses a line.

As with personal preferences for gene editing, there are wide differences on this issue by religious commitment. Fully 64% of those with a high level religious commitment say the idea of gene editing for healthy babies goes too far and is meddling with nature. By contrast, seven-in-ten of those with low religious commitment say this technology is no different from other things humans do to better themselves.

As with personal preferences for gene editing, there are wide differences on this issue by religious commitment. Fully 64% of those with a high level religious commitment say the idea of gene editing for healthy babies goes too far and is meddling with nature. By contrast, seven-in-ten of those with low religious commitment say this technology is no different from other things humans do to better themselves.

A majority of white evangelical Protestants (61%) consider the idea of gene editing for healthy babies to be crossing a line that should not be crossed. Black Protestants and Catholics are more divided over this question. Meanwhile, about eight-in-ten self-identified atheists (81%) and agnostics (80%) and roughly six-in-ten of those with no particular religious affiliation (58%) consider the idea of gene editing to be in keeping with other ways that humans try to better themselves.

Uncertainty, divisions over moral acceptability of gene editing

There is a large degree of uncertainty among Americans about whether gene editing is morally acceptable. A plurality of Americans (40%) say they are not sure whether it would be morally acceptable or not to edit a baby’s genes to give that child a reduced risk of developing serious diseases in their lifetime. Those who do express an opinion are evenly divided between those who consider gene editing for this purpose morally acceptable (28%) and those who consider it morally unacceptable (30%).

There is a large degree of uncertainty among Americans about whether gene editing is morally acceptable. A plurality of Americans (40%) say they are not sure whether it would be morally acceptable or not to edit a baby’s genes to give that child a reduced risk of developing serious diseases in their lifetime. Those who do express an opinion are evenly divided between those who consider gene editing for this purpose morally acceptable (28%) and those who consider it morally unacceptable (30%).

Among those with a view about this issue, there are wide differences by religious commitment. People with high religious commitment are more likely to say gene editing is morally unacceptable, while the balance of opinion leans in the opposite direction among those low in religious commitment.

‘Designer babies’ and views about genetic modification

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey asked people’s views about genetically modifying babies under two circumstances: in order to reduce a baby’s risk of serious diseases and conditions or to improve a baby’s intelligence. U.S. adults were closely split over whether it was “an appropriate use of medical advances” (46%) or “taking medical advances too far” (50%) to modify a baby’s genetic characteristics in order to reduce their risk of serious diseases. But, an overwhelming majority of adults (83%) said that modifying genetic characteristics to make a baby more intelligent was “taking medical advances too far.” Those who regularly attend worship services were more likely to consider genetic modifications for either purpose to be taking medical advances too far. Another 2014 Pew Research Center survey conducted with Smithsonian Magazine on public expectations for the future found two-thirds of Americans (66%) thought the possibility of parents being able to change the DNA of their children to produce smarter, healthier or more athletic offspring would be a change for the worse; 26% said this would be a change for the better.

Moral judgments about gene editing also vary by religious affiliation. Relatively few white evangelical Protestants and black Protestants say it is morally acceptable; just 16% and 15%, respectively. But a majority of atheists (60%) and half of agnostics (50%) say gene editing is morally acceptable.

Moral judgments about gene editing also vary by religious affiliation. Relatively few white evangelical Protestants and black Protestants say it is morally acceptable; just 16% and 15%, respectively. But a majority of atheists (60%) and half of agnostics (50%) say gene editing is morally acceptable.

Atheists and agnostics, meanwhile, are unlikely to call gene editing morally unacceptable; only about one-in-ten in each group say this is the case. By contrast, 43% of white evangelical Protestants say gene editing is morally unacceptable.

Still, substantial shares across all major religious groups – including roughly half of black Protestants and Hispanic Catholics – say they are not sure whether gene editing is morally acceptable.

To better understand people’s thinking about these issues, the Pew Research survey asked respondents to explain, in their own words, the reasons for their moral judgments about gene editing. The most common reasons mentioned by those with moral objections to gene editing referenced a belief that it would be altering “God’s plan” (34%) or that it would be going against nature or crossing a line we should not cross (26%), with some linking this idea to treating humans as a science experiment.

Other reasons Americans find gene editing to be morally unacceptable include the possibility of someone abusing the technology (9%); unintended consequences that may not be readily apparent until after implementation (8%); and the feeling that editing the genes of already-healthy people is unnatural or unnecessary (5%). Some 28% of those who say gene editing is morally unacceptable gave a different reason for feeling this way; an additional 27% did not give a reason.

Overall, 28% of U.S. adults say gene editing to give healthy babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions would be morally acceptable. The most common reasons for this point of view linked gene editing to other ways humans strive to improve themselves (32%), including some who framed this concept in terms of a moral responsibility for humans to use these tools if available and for parents to protect and improve a child’s health to the greatest extent possible. Another 21% mentioned improvements to society that would stem from gene editing, such as greater safety, health and productivity.

A plurality of adults –40% – is uncertain about the moral acceptability of gene editing for this purpose. While many of these respondents are simply unsure of their thinking or need more information on this issue, those who offered an explanation for their views were more likely to cite negative (53%) than positive (11%) effects of gene editing for society.

Public expects more negative than positive outcomes for society from gene editing

If gene editing is used to give healthy babies a reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions, Americans expect society to change. Nearly half of adults (46%) say such a development would change society “a great deal,” while 35% say it would change society “some” and just 17% say it would bring “not too much” or no change to society as whole.

If gene editing is used to give healthy babies a reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions, Americans expect society to change. Nearly half of adults (46%) say such a development would change society “a great deal,” while 35% say it would change society “some” and just 17% say it would bring “not too much” or no change to society as whole.

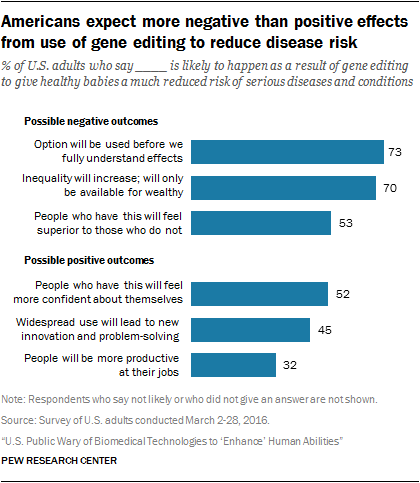

A majority of U.S. adults expect the advent of gene editing could lead to widespread negative consequences for society. About three-quarters of adults (73%) say this technology would likely be used before the health effects are fully understood, and seven-in-ten say inequality would be prone to increase because gene editing would only be available for the wealthy.

A majority of U.S. adults expect the advent of gene editing could lead to widespread negative consequences for society. About three-quarters of adults (73%) say this technology would likely be used before the health effects are fully understood, and seven-in-ten say inequality would be prone to increase because gene editing would only be available for the wealthy.

A sizeable share of the public also sees the potential for positive outcomes, too, including about half who see increases in confidence for recipients of gene editing.

Acceptance of gene editing slightly higher for health effects that are less extreme

The survey asked a number of questions to tease out the way different possible extents of gene-editing technology would affect public thinking about the issue. In a hypothetical scenario in which the health effects of gene editing would make a person far healthier than any human known to date, Americans are more likely to say it would be taking the technology too far (54%) than to say it would be an appropriate use of technology (42%).

The survey asked a number of questions to tease out the way different possible extents of gene-editing technology would affect public thinking about the issue. In a hypothetical scenario in which the health effects of gene editing would make a person far healthier than any human known to date, Americans are more likely to say it would be taking the technology too far (54%) than to say it would be an appropriate use of technology (42%).

By comparison, people are more positive about gene editing when it has less-extreme health effects. In alternate scenarios in which gene editing would make a person always equally healthy to the average person today or much healthier than the average person today, Americans are somewhat more likely to see this as an appropriate use of technology than to say it is taking technology too far.

Greater acceptance of gene editing if there is control of its effects

Americans are more inclined to see gene editing that would give healthy babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions as acceptable under conditions that give those undergoing such procedures more control. For example, 41% of U.S. adults say gene editing would be more acceptable to them if people could choose which diseases and conditions are affected by the genetic modifications. By the same token, if the effects of gene editing would be permanent and irreversible, 37% of adults say gene editing would be less acceptable.

Americans are more inclined to see gene editing that would give healthy babies a much reduced risk of serious diseases and conditions as acceptable under conditions that give those undergoing such procedures more control. For example, 41% of U.S. adults say gene editing would be more acceptable to them if people could choose which diseases and conditions are affected by the genetic modifications. By the same token, if the effects of gene editing would be permanent and irreversible, 37% of adults say gene editing would be less acceptable.

A key concern among bioethicists stems from the potential long-term implications of a type of gene editing that could change the human gene pool, known as germline editing. A person who undergoes germline editing would pass along their modified genes to any descendants; alternatively, gene editing done only in somatic cells would not be passed on to future offspring. Asked specifically about this possibility, people are more reluctant to embrace gene editing when it could affect future generations. Roughly half of adults (49%) say gene editing would be less acceptable to them if the effects “changed the genetic makeup of the whole population.” By contrast, about a third of Americans (34%) say they see an alternate scenario in which the effects of gene editing are limited to a single person as more acceptable.

A key concern among bioethicists stems from the potential long-term implications of a type of gene editing that could change the human gene pool, known as germline editing. A person who undergoes germline editing would pass along their modified genes to any descendants; alternatively, gene editing done only in somatic cells would not be passed on to future offspring. Asked specifically about this possibility, people are more reluctant to embrace gene editing when it could affect future generations. Roughly half of adults (49%) say gene editing would be less acceptable to them if the effects “changed the genetic makeup of the whole population.” By contrast, about a third of Americans (34%) say they see an alternate scenario in which the effects of gene editing are limited to a single person as more acceptable.

The details of how gene editing is accomplished and assessed for this purpose are complex. According to experts, gene editing – whether for therapeutic purposes or enhancement – is likely to involve testing on human embryos. Indeed, the first research using CRISPR on human embryos was approved in the UK as of February 2016. When survey respondents are asked to specifically consider the possibility that gene editing would involve testing on human embryos, most adults (54%) say this would make gene editing less acceptable to them.

The details of how gene editing is accomplished and assessed for this purpose are complex. According to experts, gene editing – whether for therapeutic purposes or enhancement – is likely to involve testing on human embryos. Indeed, the first research using CRISPR on human embryos was approved in the UK as of February 2016. When survey respondents are asked to specifically consider the possibility that gene editing would involve testing on human embryos, most adults (54%) say this would make gene editing less acceptable to them.

The more religious Americans are, the more likely they are to oppose testing of gene-editing technology on human embryos. Fully two-thirds of highly religious adults say having to test the technology on human embryos would make gene editing less acceptable to them, compared with 42% of Americans with a low level of religious commitment.

When it comes to members of different religious groups, majorities of Protestants – including two-thirds of white evangelicals – and Catholics say gene editing that involved testing on human embryos would be less acceptable to them. Half of those with no particular religious affiliation (50%) also say testing on human embryos would make gene editing less acceptable.

Would benefits of gene editing outweigh downsides?

Would benefits of gene editing outweigh downsides?

After answering a number of questions about personal reactions to this idea and the likely effects for society of gene editing for this purpose, respondents were asked for an overall take on the expected effects on society as a whole of gene editing to give healthy babies a reduced risk of serious diseases. Slightly more Americans expect the benefits for society would outnumber the downsides of gene editing (36%). But some 28% say the downsides would outpace benefits, and a third (33%) say the downsides and benefits would even out.

After answering a number of questions about personal reactions to this idea and the likely effects for society of gene editing for this purpose, respondents were asked for an overall take on the expected effects on society as a whole of gene editing to give healthy babies a reduced risk of serious diseases. Slightly more Americans expect the benefits for society would outnumber the downsides of gene editing (36%). But some 28% say the downsides would outpace benefits, and a third (33%) say the downsides and benefits would even out.

Those with a high level of religious commitment are more likely to say the downsides would outnumber the benefits to society than they are to say the benefits would be more numerous (38% vs. 23%). But the opposite is true of those in the low religious commitment category; 46% say the benefits would outnumber the downsides, while 18% say there would be more downsides.

About six-in-ten atheists (59%) and roughly half of agnostics (53%) say the benefits of gene editing for this purpose would outnumber the downsides for society overall, while relatively few in these groups say the downsides would be greater. People with other religious identities are more divided on this question.

Scientific and Ethical Debates

Scientific and Ethical Debates Perspectives on Human Enhancement

Perspectives on Human Enhancement The scientific and ethical elements of Human Enhancement

The scientific and ethical elements of Human Enhancement