Before you read the report

Test your science knowledge by taking the interactive quiz. The short quiz tests your knowledge of questions recently asked in a national poll. After completing the quiz, you can compare your score with the general public and with people like yourself.

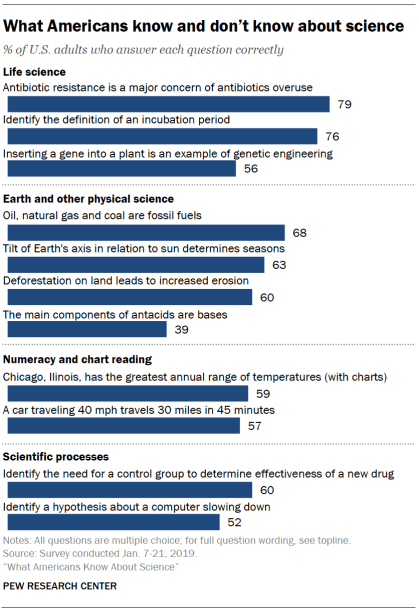

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that many Americans can answer at least some questions about science concepts – most can correctly answer a question about antibiotics overuse or the definition of an “incubation period,” for example. But other concepts are more challenging; fewer Americans can recognize a hypothesis or identify that bases are the main components of antacids.

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that many Americans can answer at least some questions about science concepts – most can correctly answer a question about antibiotics overuse or the definition of an “incubation period,” for example. But other concepts are more challenging; fewer Americans can recognize a hypothesis or identify that bases are the main components of antacids.

The survey, conducted Jan. 7 to 21, 2019, takes stock of the degree to which the public shares a common understanding of science facts and processes in an era of easy access to information and sometimes-intense debate over what information is true and false.

Americans’ knowledge of specific facts connected with life sciences and earth and other physical sciences varies, of course. About eight-in-ten (79%) correctly identify that antibiotic resistance is a major concern about the overuse of antibiotics. A similar share (76%) know an incubation period is the time during which someone has an infection but is not showing symptoms.

The most challenging question in the set: What are the main components of antacids that help relieve an overly acidic stomach? About four-in-ten correctly answer bases (39%).

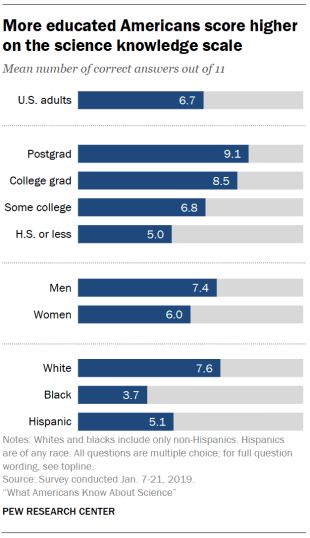

Americans give more correct than incorrect answers to the 11 questions. The mean number of correct answers is 6.7, while the median is 7. About four-in-ten Americans (39%) get between nine and 11 correct answers, classified as having high science knowledge on the 11-item scale or index. Roughly one-third (32%) are classified as having medium science knowledge (five to eight correct answers) and about three-in-ten (29%) are in the low science knowledge group (zero to four correct answers).

Science covers numerous fields and encompasses a vast amount of information, and the index of science knowledge can cover only a small slice of this information. However, the rationale for the scale stems from the fact people who happen to know more from this set of questions are also likely to know more about the vast array of science information, generally.

One goal for a useful scale or index of this sort is that it differentiates between individuals at each level of knowledge, particularly between those with a high level of knowledge and those with medium or low knowledge.1 Item-response modeling suggests that the scale generally performs well in this regard.2 See the Methodology for details.

More-educated Americans score highest on science knowledge; whites generally score higher than blacks and Hispanics

There are striking differences in levels of science knowledge by education as well as by racial and ethnic group. Men tend to score higher than women on the science knowledge scale, but gender differences are not consistent across questions in the scale. And political party groups are roughly similar in their overall levels of science knowledge, although conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats tend to score higher on the scale than do their more moderate counterparts.

There are wide educational differences on science knowledge

Americans with a postgraduate degree get about four more questions correct, on average, than those with a high school degree or less education (9.1 of 11 questions vs. 5 of 11). Roughly seven-in-ten (71%) Americans with a postgraduate degree are classified as high in science knowledge, answering at least nine of 11 items correctly. By contrast, about two-in-ten (19%) of those with a high school degree or less perform as well on the scale.

And on each of the 11 questions, those with a postgraduate degree are at least 27 percentage points more likely to choose the correct answer than those with a high school degree or less.

And on each of the 11 questions, those with a postgraduate degree are at least 27 percentage points more likely to choose the correct answer than those with a high school degree or less.

These large education differences are consistent with past Center surveys on science knowledge and with the National Science Board’s index of factual science knowledge.3

Wide differences in science knowledge on education may reflect greater exposure to science training at higher levels of schooling. People may also encounter science information informally by going to museums or zoos or through participation in science-related activities. A 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that 62% of U.S. adults had encountered science through one of these informal institutions or events in the past year: a national, state or county park (47%); a zoo or aquarium (30%); a science and technology center or museum (18%); a natural history museum (16%); or a science lecture (10%). Those with more education were also more likely to have participated in any of these informal science activities.

News media can also inform people about science and new scientific developments. Most Americans (71%) reported they were at least somewhat interested in science news in the same 2017 Center survey, though 68% of Americans said they were more likely to get science news because they happen to come across it, while 30% said they seek it out. Americans with more education were more likely than those with a high school degree or less education to report that they seek out science news.

There are substantial differences in levels of science knowledge by race and ethnicity

Whites are more likely than Hispanics or blacks to score higher on the index. Whites get an average of 7.6 correct out of 11 questions, while Hispanics average 5.1 correct answers and blacks 3.7 correct answers.4 Roughly half of whites (48%) are classified as having high science knowledge on the scale, answering at least nine questions correctly, compared with 23% of Hispanics and 9% of blacks.

Differences by race and ethnicity on science knowledge could be tied to several factors such as educational attainment and access to science information. However, differences between the racial/ethnic groups on science knowledge hold even after controlling for education levels in a regression model.

Previous Pew Research Center surveys have also found differences between whites, blacks and Hispanics on science knowledge questions. Similarly, Center analysis of the factual science knowledge questions from the General Social Surveys (GSS) conducted between 2006 and 2016 found that, on average, whites got 6.1 out of 9 correct answers, while blacks got 4.4 correct answers and Hispanics got 4.8 correct answers.5 Among those with a college degree or more, on average, whites had 1.6 more correct answers than blacks and 0.8 more correct answers than Hispanics. These differences are consistent with findings from Nick Allum and colleagues who used a regression analysis with additional controls for socioeconomic status.6

Black and Hispanic students also tend to score lower on standardized tests on science at the elementary and high school levels, even as these achievement gaps have narrowed over time. And a Pew Research Center analysis of the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress found whites were more likely than blacks and Hispanics to express interest in science in high school.

Men tend to score higher than women on science knowledge, but the differences vary across questions

The survey also finds men generally score higher than women on the science knowledge scale. On average, men answer 7.4 questions correctly, while women average 6.0. About half of men (49%) score high on the scale, compared with 30% of women. But gender differences are not consistent across questions.

Science and Engineering Indicators reports over the past several years have suggested that men tend to do better on knowledge of physical science facts while men and women perform about equally on facts related to the life sciences.7 The Center survey includes only a handful of questions in each domain. Men are more likely than women to answer the four questions related to earth and other physical sciences correctly. Two of the three questions related to life sciences in the survey find men and women are about equally likely to know the correct response. For example, 80% of men and 77% of women correctly say that antibiotic resistance is a major concern of overuse of antibiotics.

Republicans and Democrats hold similar levels of science knowledge

Republicans and Democrats have similar levels of understanding about science, in contrast to the wide differences by education and racial and ethnic group. Republicans and independents who lean to the Republican Party average seven correct answers, while Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party average 6.6.

Republicans and Democrats have similar levels of understanding about science, in contrast to the wide differences by education and racial and ethnic group. Republicans and independents who lean to the Republican Party average seven correct answers, while Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party average 6.6.

Those at the ends of the political spectrum – liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans – score higher than those in the middle, however. On average, liberal Democrats get 7.8 correct answers and conservative Republicans score 7.4. In comparison, moderate and liberal Republicans get an average of 6.5 correct answers, while moderate and conservative Democrats get an average of 5.6.

These findings are consistent with a 2016 Center survey that used a different science knowledge scale and also found partisans to hold similar levels of science knowledge. That study found a tendency for liberal Democrats and, to a lesser extent, conservative Republicans to score higher on the scale than those in the middle of the political spectrum.

Older and younger Americans have roughly similar scores on the science knowledge index

Science knowledge levels are similar by age, although there are some differences across questions on the scale. On average, those ages 65 and older get 7.1 out of 11 questions correct and those ages 18 to 29 get 6.6 correct. In statistical models predicting science knowledge and controlling for gender, race/ethnicity and education, there are no significant differences by age (see Appendix for more details). Past Center surveys also found age patterns in science knowledge tended to vary across questions.

Details on education, race and ethnicity, gender, and political party differences are shown in the Appendix.

Public understanding of the scientific method also connects with education levels

People’s understanding of scientific processes and how scientific knowledge accumulates may help them navigate ongoing debates over science connected with issues such as climate change, childhood vaccines and genetically modified foods.

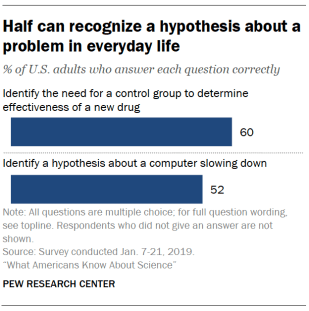

The survey includes two questions designed to test understanding of scientific processes. Six-in-ten Americans (60%) can identify that adding a control group is the best of four options to use to test whether an ear infection medication is effective. And 52% correctly identify a scientific hypothesis about a computer slowing down.

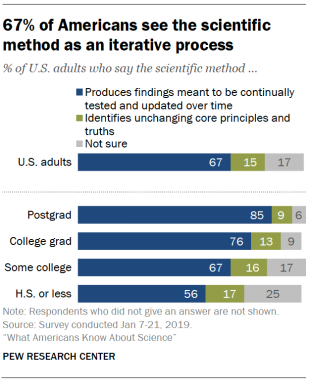

One other question, not included as part of the scale, asked survey respondents which of two statements best describes the scientific method: That it produces findings meant to be continually tested and updated over time, or that it identifies unchanging core principles and truths. Two-thirds of Americans (67%) say the scientific method is designed to be iterative, producing findings that are continually tested and updated, while 15% say the method produces unchanging core principles and truths, and 17% say they are not sure.

Americans with higher levels of education are more inclined to see the scientific method as producing results that are meant to be continually tested and updated over time. Three-quarters or more of those with a postgraduate (85%) or college degree (76%) say this, compared with 56% among those with a high school education or less.

Science knowledge is often hailed as important for society, but its role in public attitudes can be nuanced

Higher levels of science knowledge are often seen as important characteristics for individuals, communities and the citizenry as a whole.8

As a practical matter, science knowledge can help individuals navigate a variety of everyday situations, such as making health care decisions or deciding what to eat. Communities can benefit from higher levels of science knowledge, particularly as they make sense of potential health hazards in their environment. And, as science continues to advance and new scientific debates emerge on issues such as climate change and gene editing, a more informed citizenry is seen as better able to make sense of this information and engage in civic discourse around these topics.

Many in the scientific community have looked to public knowledge and understanding about science as a potential driver of support for specific positions that align with scientific consensus in areas of “settled science.” But a long history of research in pursuit of what is often called a “deficit model” of public attitudes finds little support for the idea. A meta-analysis of past research has shown a modest positive relationship between science knowledge and people’s general support for science or scientific research.9 However, levels of science knowledge do not typically have a direct relationship with positions on specific issues, such as whether to mandate the vaccine for measles, mumps and rubella for children who attend public schools.

And on some issues, science knowledge can have a more complicated, indirect role. When it comes to public views about climate and energy issues, partisanship appears to serve as an anchoring point in how people apply their knowledge.10 For example, a 2016 Pew Research Center survey found that 93% of Democrats with a high level of knowledge about science said climate change is mostly due to human activity, compared with about half (49%) of Democrats with low science knowledge who said this. By contrast, Republicans with a high level of science knowledge were no more likely than those with a low level of knowledge to think climate change is mostly due to human activity. The same pattern was found for people’s beliefs about energy issues.

Science Knowledge Quiz

Science Knowledge Quiz