An important throughline in the Pew Research Center survey findings is the importance of representation and visibility for Hispanic Americans in science and allied fields.

At a big-picture level, many Hispanic Americans report that scientists as a group have limited openness to Hispanic people in the profession. Roughly a quarter of Hispanic Americans consider scientists as a group to be very welcoming to fellow Hispanic professionals in these roles. Similarly, fewer than half of Hispanic Americans consider science an area where Hispanic Americans have reached the highest levels of professional achievement. Ratings of scientists on each of these two metrics rank toward the bottom of a list of eight other professional groups.

There has been a rise in the share of Hispanic students attending and graduating from college as well as a rise in the share of Hispanic students earning a bachelor’s degree in a STEM field (up from 8% in 2010 to 12% in 2018, according to Center analysis of U.S. Department of Education data). Even so, Hispanic students remain underrepresented in STEM degree programs, relative to all college graduates.

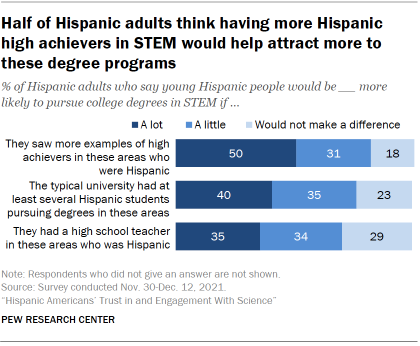

Asked to think about several possible ways to increase the number of young Hispanic people who pursue college degrees in STEM fields, most Hispanic Americans endorse the idea that more high achievers in STEM who are Hispanic would serve as a catalyst for more young Hispanic people to follow in their footsteps.

Among Hispanic college graduates working in a STEM occupation – a group likely to have completed high-level classes in STEM subjects – many recall a mix of positive and negative experiences in the classroom. Most say they had at least one of three positive experiences in their most recent STEM schooling, such as being encouraged to pursue more classes in these fields – as do most college-educated STEM workers in the general population. But a larger share of Hispanic college graduates working in STEM than in the general population of STEM workers say they experienced some form of mistreatment in their STEM schooling including being treated as if they couldn’t understand the subject matter, made to feel like they don’t belong or receiving repeated negative comments about their race.

Hispanic college graduates working in STEM include both U.S.-born and foreign-born Hispanic adults, some of whom may have completed STEM schooling in a foreign country. However, among college-educated Hispanic adults, there are hardly any differences between those born in the U.S. and those born in another country when it comes to the shares who have experienced these positive or negative STEM schooling experiences.

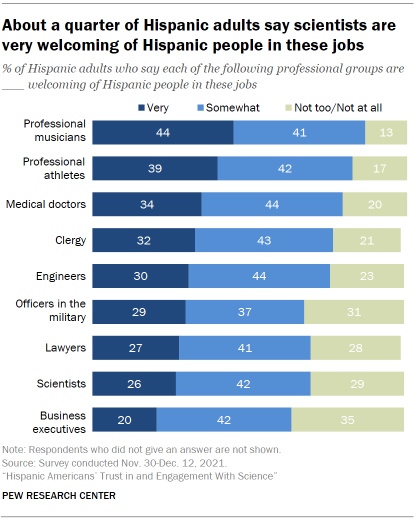

Fewer than half of Hispanic Americans see scientists as very welcoming to Hispanic professionals

Hispanic Americans continue to be underrepresented in the STEM workforce. According to Pew Research Center analysis of federal government data, Hispanic workers make up 17% of total employment across all occupations, but just 8% of all STEM workers. Hispanic workers are underrepresented across all STEM job types, including health-related jobs, life sciences, math, physical sciences, computer and engineering jobs.

Perceptions of STEM professions could play a role in these patterns. The Center survey asked Hispanic adults for their perceptions of scientists, engineers and a range of other professional groups.

When it comes to perceptions of openness to Hispanic professionals, scientists are rated near the bottom of the nine groups considered in the survey.

Professional musicians followed by professional athletes are seen as the most open; about four-in-ten or more Hispanic Americans rate each of these groups as very welcoming to Hispanic professionals in these roles.

About a third of Hispanic adults say medical doctors are very welcoming to Hispanic professionals (34%), while 44% say medical doctors are somewhat welcoming and two-in-ten consider medical doctors to be not too or not at all welcoming to Hispanic professionals in medicine.

Three-in-ten Hispanic Americans say that engineers, as a group, are very welcoming; 26% of Hispanic adults say scientists are very welcoming to Hispanic professionals in these occupations.

Business executives are rated the lowest of the nine professional groups: 20% of Hispanic Americans say business executives are very welcoming to Hispanic professionals in these positions, 42% say business executives are somewhat welcoming and 35% say business executives are not too or not at all welcoming to Hispanic people in these jobs.

Hispanic Americans hold roughly similar views of the openness of these three STEM professional groups to Hispanic professionals – scientists, engineers and medical doctors – across education, age and nativity. See Appendix for details.

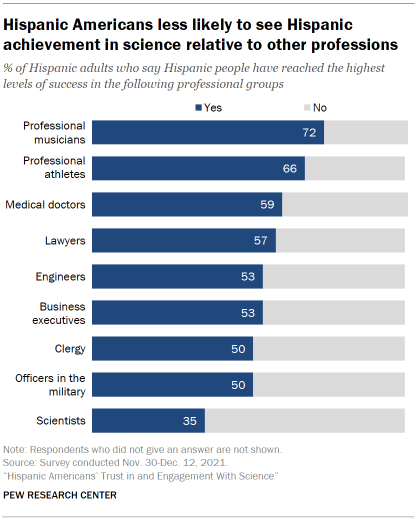

The survey also asked whether or not people saw prominent achievement for Hispanic people across a range of professional groups. (Half of the survey respondents rated how welcoming each professional group is and half rated whether or not Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success in each professional group.)

Here, too, the professions seen as most open to Hispanic people include professional musicians and professional athletes, while scientists rank at the bottom of the list.

About seven-in-ten (72%) Hispanic adults say that Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success as professional musicians, while two-thirds (66%) say this of professional athletes. Majorities of Hispanic adults say that Hispanic people have achieved at the highest levels as medical doctors (59%) and lawyers (57%).

Engineers are at the median of the nine professional groups, with 53% of Hispanic adults saying that Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success as engineers.

Scientists were least likely to be seen in this way; 35% of Hispanic adults say that Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success as scientists.

Perceptions of the three STEM professions asked about are broadly similar across demographic characteristics. However, foreign-born Hispanic adults are more inclined to say that Hispanic people have reached the highest levels of success as scientists, engineers and medical doctors; they are also more likely to see prominent Hispanic achievement for other professional groups, including lawyers and business executives.

Hispanic men are more likely than women to say Hispanic people have reached high levels of achievement as engineers (59% vs. 48%). Hispanic men are also more likely than women to rate engineers as very welcoming to Hispanic professionals. See Appendix for details.

Focus group participants spoke to the importance of visibility for Hispanic Americans in these professions when questioned about ways to build trust in scientists among Hispanic Americans. One participant said:

“I think we need to know more Latino scientists. I think … well, actually, I don’t know any Latino scientists that I would say, “Oh yes. That’s that scientist … So maybe if we knew some scientists that made a discovery that was Latino we would trust science more.” – Hispanic woman, age 25-39

Another talked about the importance of visible Hispanic achievements in science this way:

“If scientists are trying to get the attention of Latinos, yes, it is important that we see and relate to them in the health care world or anywhere that we see somebody relatable. I believe that if more knowledge or presence is known about scientists and what they discover and I don’t know, a small commercial, a spokesperson, somebody that everybody trusts in the Latino culture, artists, things that can vouch for them, I think that will bring awareness to it.” – Hispanic man, age 25-39

More Latino high-achievers in STEM seen as important for increasing Latino representation in degree programs

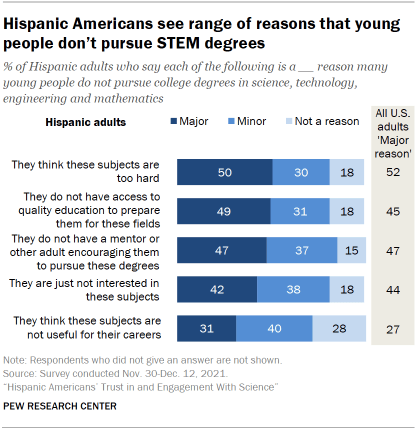

Latinos see a number of factors as influencing why some young people do not pursue STEM degrees including a belief that STEM subjects are too hard, limited access to high-quality education and lack of a mentor that encourages them to pursue these degrees.

Half of Latino adults say that a major reason young people choose not to pursue STEM in college is because they think these subjects are too hard, with another 30% saying this is a minor reason. (Note that these questions refer to young people, generally, without regard to a particular racial or ethnic group.)

Around half of Latinos also see lack of access to quality education to prepare for STEM fields (49%) or not having a mentor encouraging them to pursue a STEM degree (47%) as major reasons young people choose not to study STEM subjects in higher education.

About four-in-ten Latinos say a major reason that young people do not pursue STEM degrees is because they are just not interested in these subjects (42%). Somewhat smaller shares of Latinos (31%) say that young people do not pursue STEM degrees because they think these subjects are not useful for their careers.

The shares of Hispanic adults saying each of these is a major deterrent to young people pursuing STEM degrees are similar to the shares of U.S. adults overall who say this.

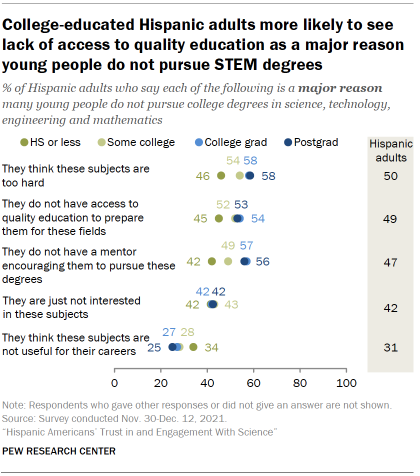

In thinking about reasons why more young people do not pursue STEM degrees, Hispanic adults with higher levels of education see some of these reasons as more important, especially the role of a mentor.

A majority of Hispanic adults with a postgraduate (56%) or college degree (57%) say not having mentors to encourage them is a major reason young people do not pursue STEM degrees. A smaller share (42%) of Hispanic adults with a high school degree or less education say this.

College-educated Hispanic Americans are also more inclined to think that seeing STEM subjects as too difficult is a major reason more young people do not pursue degrees in these fields; 58% say this is a major reason, compared with 46% of Hispanic adults with a high school degree or less education.

Those with higher levels of education are more likely than those with a high school degree or less education to see lack of access to quality education as a major reasons young people choose not to pursue STEM degrees.

A 2021 Pew Research Center analysis found increasing shares of Hispanics were enrolling in college and earning bachelor’s degrees in STEM fields prior to the pandemic. Even with the recent gains, Hispanic Americans were still underrepresented among STEM degree recipients in the most recent data available on this from the U.S. Department of Education. In 2018, 12% of Hispanic college graduates earned a degree in a STEM field, lower than the share of Hispanic graduates among all bachelor’s degree recipients (15%).

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, undergraduate enrollment declined in the U.S. Among Hispanic students, undergraduate enrollment declined by 7% from fall 2019 to fall 2021, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Overall undergraduate enrollment was down by a similar share (8%) over this two-year period.

An analysis of data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study found that in 2016, 44% of Hispanic college students had parents who did not attend college. In comparison, smaller shares of non-Hispanic Black students (34%), Asian (29%) and non-Hispanic White college students (22%) were first-generation college students.

Among the Hispanic adults with at least some college experience who say they are the first in their immediate family to attend college, a 56% majority say that not having a mentor is a major reason young people do not pursue college degrees in STEM. Among those with some college education who were not the first in their families to attend college, 49% see a lack of mentors as a major reason for young people not pursuing STEM studies.

When asked specifically about factors that would make young Hispanic people more likely to pursue STEM college degrees, majorities of Hispanic Americans say that more visible representation of Hispanic students in these programs would help.

Half of Hispanic Americans say that young Hispanic people would be a lot more likely to pursue a STEM degree if they saw examples of high achievers in this area who were Hispanic. Another 31% say this would make young Hispanic people at least a little more likely to pursue STEM degrees in college.

Sizable shares of Hispanic adults also say that more representation – that is, having at least several Hispanic students in STEM degree programs at the typical university – would help a lot (40%) to make young Hispanic people pursue college degrees in STEM. And 35% think that having a high school teacher in STEM subjects who was Hispanic would help a lot.

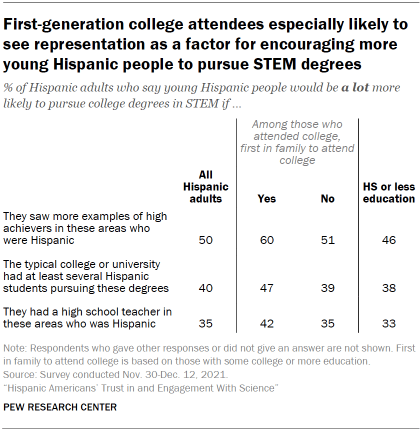

College-educated Hispanic adults are especially likely to see all three of these ideas as helpful for encouraging more young Hispanic people to pursue STEM in college. About six-in-ten of this group say that having more examples of high achievers in STEM who are Hispanic would help a lot to attract more young Hispanic adults to these degree programs. See the Appendix for details.

Among Hispanic adults who have attended college, those who were the first in their families to do so were more likely than other college attendees to say that each of these measures would make young Hispanic people more likely to pursue college degrees in STEM. For example, 60% of those who were the first in their families to attend college say that more examples of high achievers in these areas would make young Hispanic people a lot more likely to pursue STEM degrees, compared with 51% of those who were not the first in their family to attend college.

The importance of role models and representation was a common theme in focus groups discussions. Responding to a question about the importance of Hispanic STEM teachers in high school, one participant said:

“I also think that it would be good for the students to see that the Hispanic teachers are successful. And that they would be able to do the same thing.” – Hispanic woman, age 40-65

Another participant shared her personal experience with having a Hispanic STEM teacher in high school:

“I could speak from experience that in sixth grade I had an amazing teacher. She taught like a Mexican heritage club and she was also a science teacher. I really looked up to her and I could say that it was important. And now that I identified later in life as a woman, Hispanic, science teacher, I definitely think that that’s important for a young, Hispanic, girl to know. That math is an opportunity that she can go to the moon if she wants. But seeing a woman in science is going to help her, I believe. Or a young boy. But Hispanic in general, they’re going to appreciate that. Especially if they’re a person of position.” – Hispanic woman, age 20-39

Hispanic adults who predominantly speak Spanish are more likely than those who predominantly speak English to say that each of these factors would make young Hispanic people a lot more likely to pursue college degrees in STEM.2 For example, 47% of Hispanic adults who mainly speak Spanish say that the typical university having at least several Hispanic students in these degree programs would encourage more young Hispanic people to pursue STEM degrees, compared with 37% of Hispanic adults who mainly speak English. See the Appendix for details.

Hispanic STEM workers with a college degree are more likely to report positive encouragements, as well as mistreatment, in STEM schooling

Thinking back to their time in STEM education, Hispanic adults are, overall, more likely to report positive than negative experiences. Nearly all high school graduates in the U.S. are required to take at least some science, technology, engineering or math classes in order to graduate. The survey asked this group about their most recent experience with STEM classes. Among Hispanic adults with a high school degree or more education, 61% recall at least one positive experience in the STEM classroom. Still, nearly four-in-ten of this group (37%) say they had at least one of the following negative experiences: being treated as if they couldn’t understand the subject matter, made to feel like they don’t belong or receiving repeated negative comments about their race.

Around half of Hispanic adults with a high school degree or more education say that someone made them feel excited about their abilities, helped them see ways these subjects could be useful for their job or encouraged them to keep taking STEM classes (47% each).

Smaller, yet still sizable, shares of Hispanic adults with at least a high school degree recall mistreatment. Three-in-ten say that in their most recent STEM schooling, someone treated them as if they could not understand these subjects. A quarter say that someone made them feel like they did not belong in their most recent STEM schooling, and 14% of this group say that someone made repeated negative comments or slights about their race or ethnicity.

These recollections offer insight into Hispanic high school graduates’ lasting memories from STEM educational experiences, but they do not capture the full context of these experiences or the frequency – whether isolated or repeated in nature – of positive and negative experiences in STEM education.

A majority of U.S. adults (59%) who have graduated from high school report having had at least one of these positive experiences, and a third of U.S. adults report having had at least one of these negative experiences in their most recently STEM schooling. The share of high school graduates who report having had at least one negative experience in their STEM schooling is higher among Hispanic adults (37%) and all Black adults (39%) than it is among non-Hispanic White adults (30%).

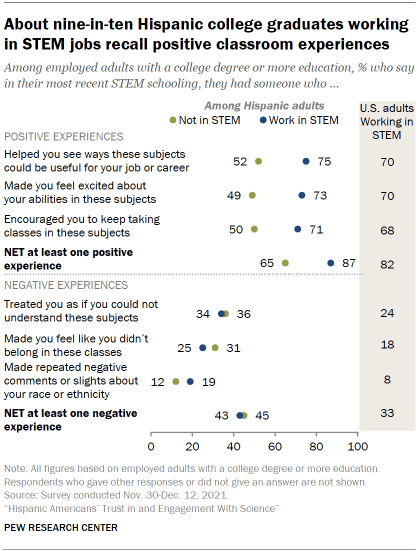

Hispanic college graduates working in STEM jobs – a group likely to have taken higher-level classes in STEM subjects – are especially likely to report positive experiences in their most recent STEM schooling.

Among this group, three-quarters say someone helped them see ways these subjects could be useful for their job or career and a similar share (73%) say someone made them feel excited about their abilities in these subjects. About seven-in-ten (71%) of this group say that someone encouraged them to keep taking classes in these subjects. In all, 87% of Hispanic college-educated STEM workers say they had at least one of these positive experiences.

Hispanic college graduates not working in STEM jobs today are much less likely to report any of these positive experiences in their most recent STEM schooling (65% say they experienced at least one). Among this group, half say they felt encouraged to keep taking classes in these subjects.

More than four-in-ten Hispanic college graduates working in STEM say that they experienced some form of mistreatment or microaggression in their most recent STEM schooling (43%). A similar share of Hispanic college graduates working in non-STEM jobs say they have had at least one of these negative experiences (45%).

Among all U.S. STEM workers with a college degree, 82% say they had at least one of these three positive experiences in their most recent STEM schooling. A third say they experienced at least one of these three forms of mistreatment in their past STEM schooling. However, there are sizable differences in experiences with the types of mistreatment by race and ethnicity. Among college-educated STEM workers, Hispanic (43%) and Black STEM workers (45%) are more likely than White STEM workers (30%) to have had one of these three negative experiences in their most recent STEM schooling.

Having had a Hispanic high school teacher in STEM subjects is associated with more positive experiences in STEM schooling overall, though this may not be a causal effect. About seven-in-ten (68%) of Hispanic high school graduates who had a Hispanic high school STEM teacher report having had at least one of these positive experiences in STEM, compared with 53% of those who did not have a Hispanic STEM teacher. Note, however, that the survey design cannot address whether or not having a Hispanic high school teacher in a STEM subject has a causal role in these experiences. See Appendix for details.