Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans are continuing to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 12,648 U.S. adults from Nov. 18 to 29, 2020.

Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

See here to read more about the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.

As vaccines for the coronavirus enter review for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the share of Americans who say they plan to get vaccinated has increased as the public has grown more confident that the development process will deliver a safe and effective vaccine. Still, the U.S. public is far from uniform in views about a vaccine. A majority says they would be uncomfortable being among the first to take it, and a sizable minority appear certain to pass on getting vaccinated.

As vaccines for the coronavirus enter review for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the share of Americans who say they plan to get vaccinated has increased as the public has grown more confident that the development process will deliver a safe and effective vaccine. Still, the U.S. public is far from uniform in views about a vaccine. A majority says they would be uncomfortable being among the first to take it, and a sizable minority appear certain to pass on getting vaccinated.

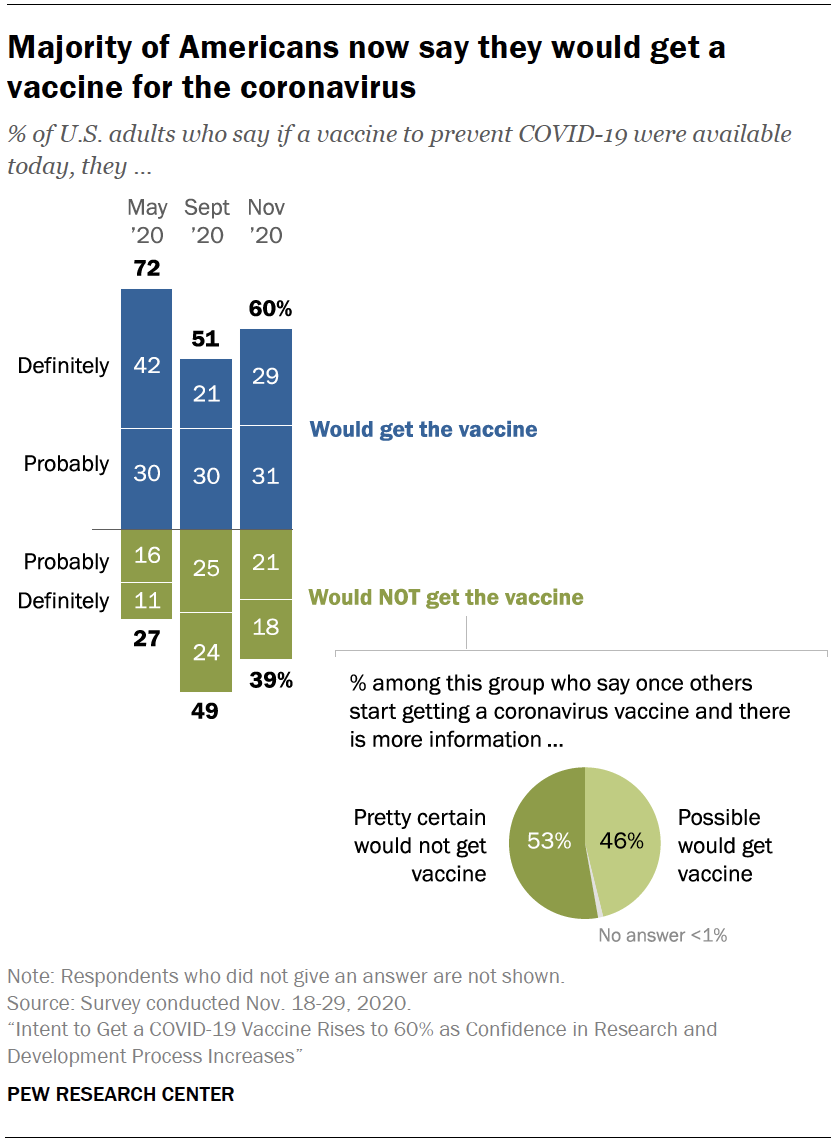

Overall, 60% of Americans say they would definitely or probably get a vaccine for the coronavirus, if one were available today, up from 51% who said this in September. About four-in-ten (39%) say they definitely or probably would not get a coronavirus vaccine, though about half of this group – or 18% of U.S. adults – says it’s possible they would decide to get vaccinated once people start getting a vaccine and more information becomes available.

Yet, 21% of U.S. adults do not intend to get vaccinated and are “pretty certain” more information will not change their mind.

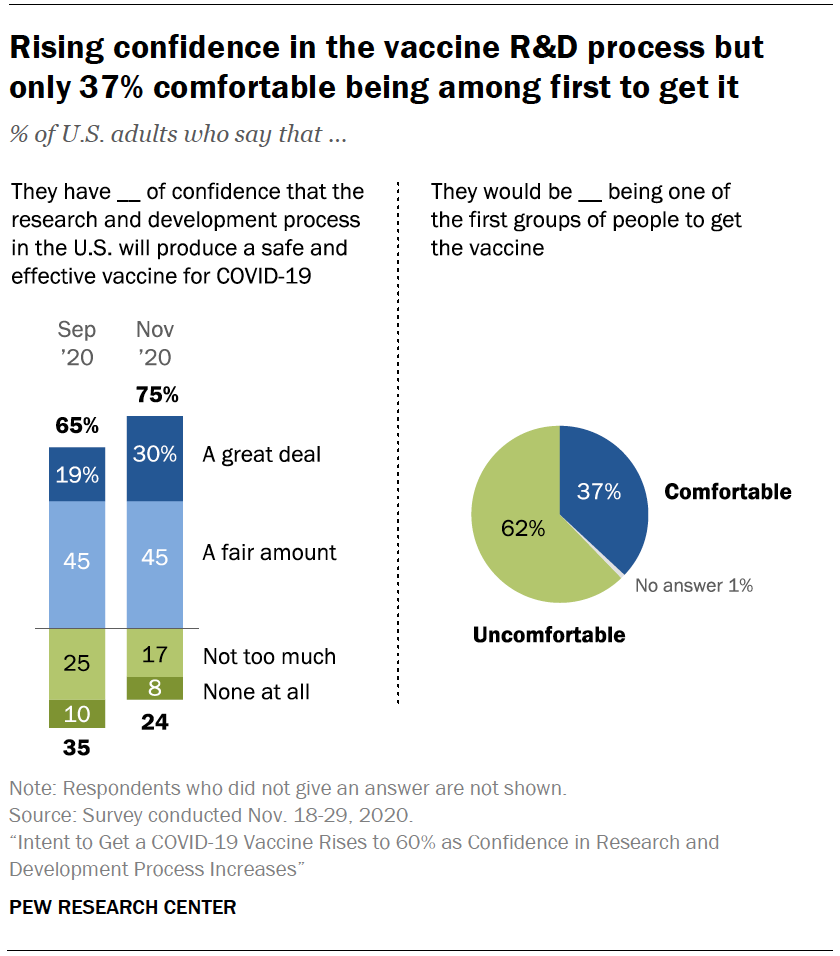

Public confidence has grown that the research and development process will yield a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19: 75% have at least a fair amount of confidence in the development process today, compared with 65% who said this in September.

Public confidence has grown that the research and development process will yield a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19: 75% have at least a fair amount of confidence in the development process today, compared with 65% who said this in September.

These findings come on the heels of preliminary analysis from two separate clinical trials that have produced vaccines that are over 90% effective; the FDA is expected to issue decisions about the emergency authorization of these vaccines in the coming weeks.

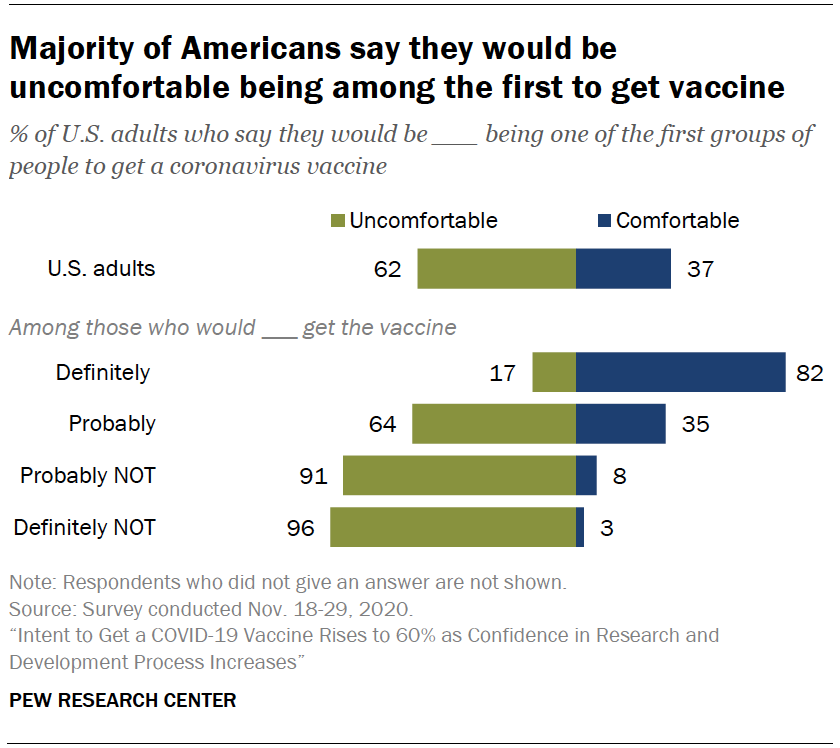

While public intent to get a vaccine and confidence in the vaccine development process are up, there’s considerable wariness about being among the first to get a vaccine: 62% of the public says they would be uncomfortable doing this. Just 37% would be comfortable.

The new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted Nov. 18 to 29 among 12,648 U.S. adults, finds that amid a rising number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S., the public’s outlook for the country has darkened: 71% say they think the worst of the outbreak is still to come, up from 59% who said this in June.

The new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted Nov. 18 to 29 among 12,648 U.S. adults, finds that amid a rising number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S., the public’s outlook for the country has darkened: 71% say they think the worst of the outbreak is still to come, up from 59% who said this in June.

And while the public continues to give hospitals and medical centers high marks for how they’ve responded to the outbreak, about half of Americans (52%) think hospitals in their area will struggle to handle the number of people seeking treatment for the coronavirus in the coming months; slightly fewer (47%) think their local medical providers will be able to handle the number of patients.

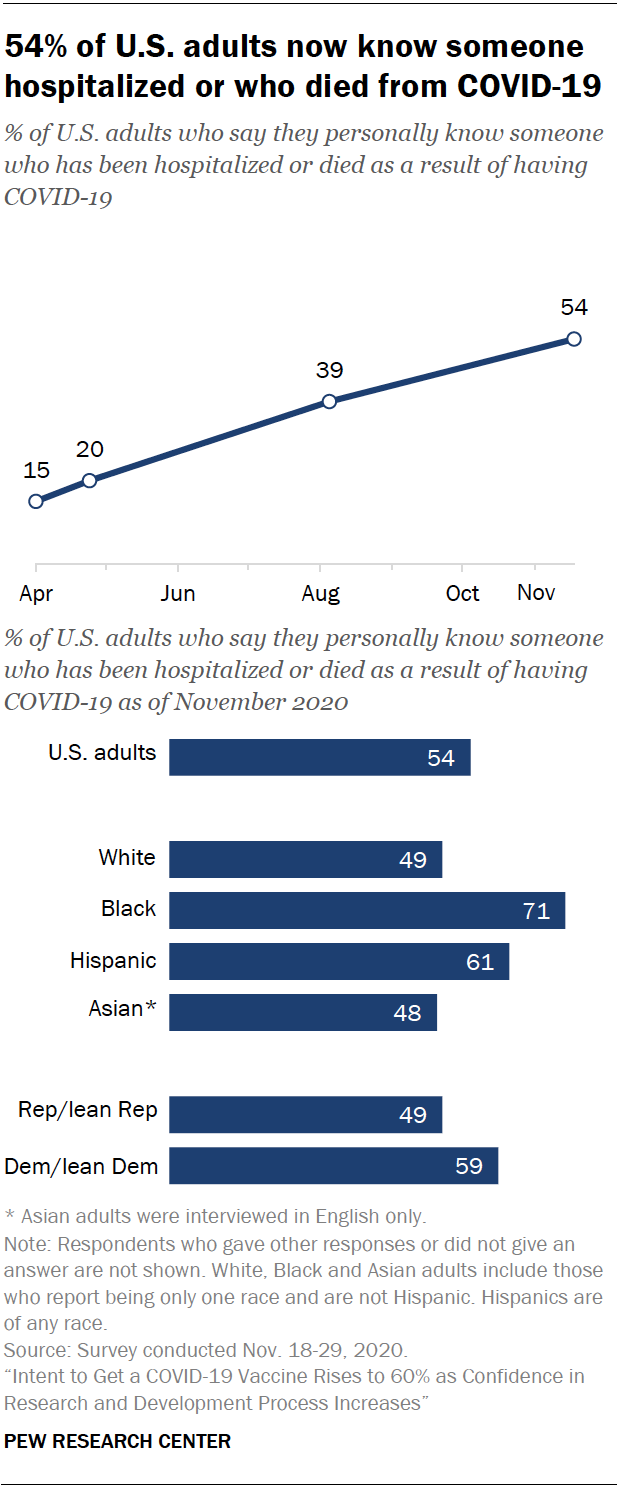

The toll of the pandemic is starkly illustrated by the 54% of Americans who say they know someone personally who has been hospitalized or died due to the coronavirus. Among Black Americans, 71% know someone who has been hospitalized or died because of COVID-19.

The survey sheds light on the complex and interrelated factors that shape intent to get a vaccine for COVID-19, chief among them are:

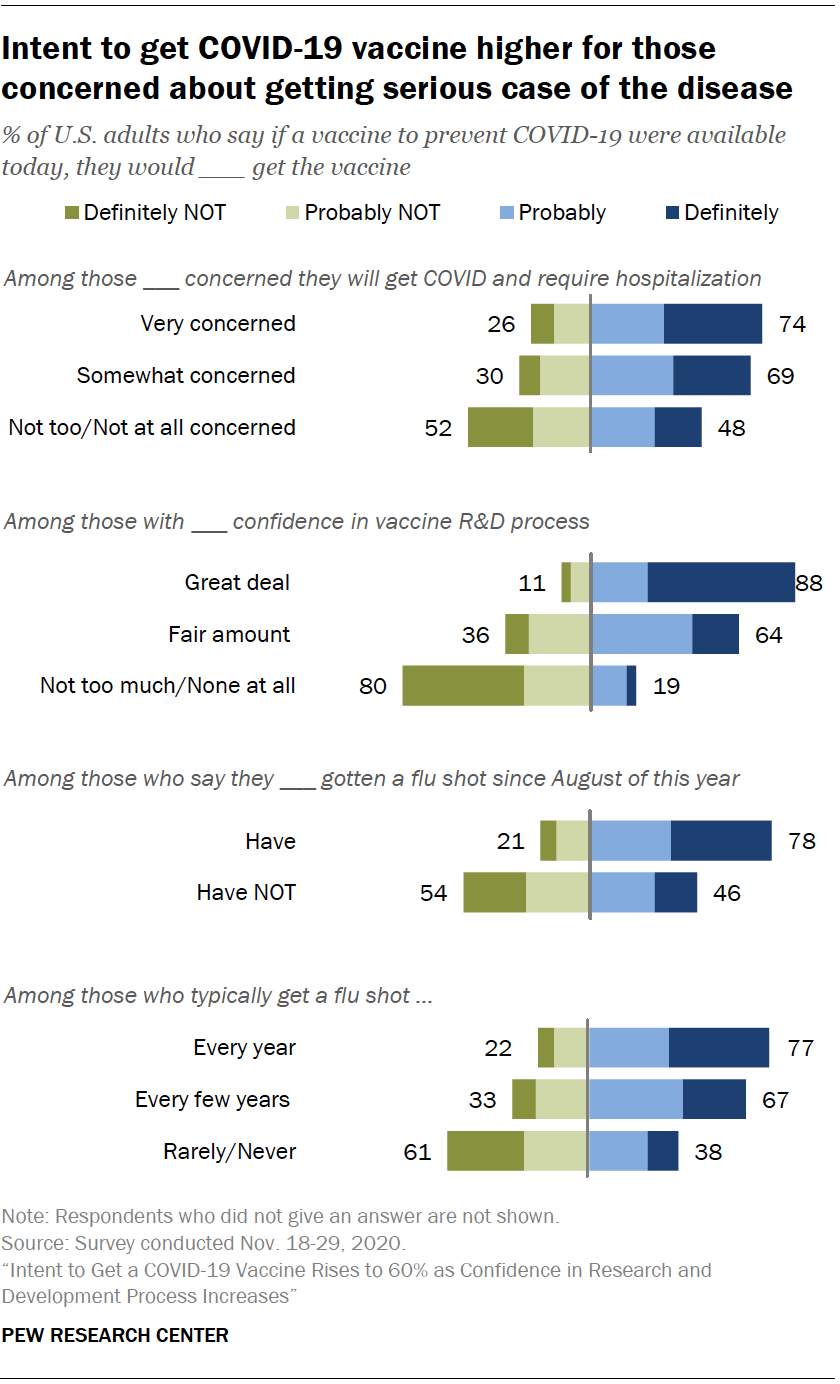

- Personal concern about getting a case of COVID-19 that would require hospitalization. Those most concerned about getting a serious case of the coronavirus indicate a higher likelihood of getting a vaccine. Those who see little personal need by this metric are closely divided over whether they would get vaccinated.

- Trust in the vaccine development process. Expressing confidence that the research and development process will yield a safe and effective vaccine is tied to higher levels of intent to get vaccinated.

- Personal practices when it comes to other vaccines. Those who say they get a flu shot yearly are much more likely than those who rarely or never do so to say they would get a vaccine for the coronavirus if one were available.

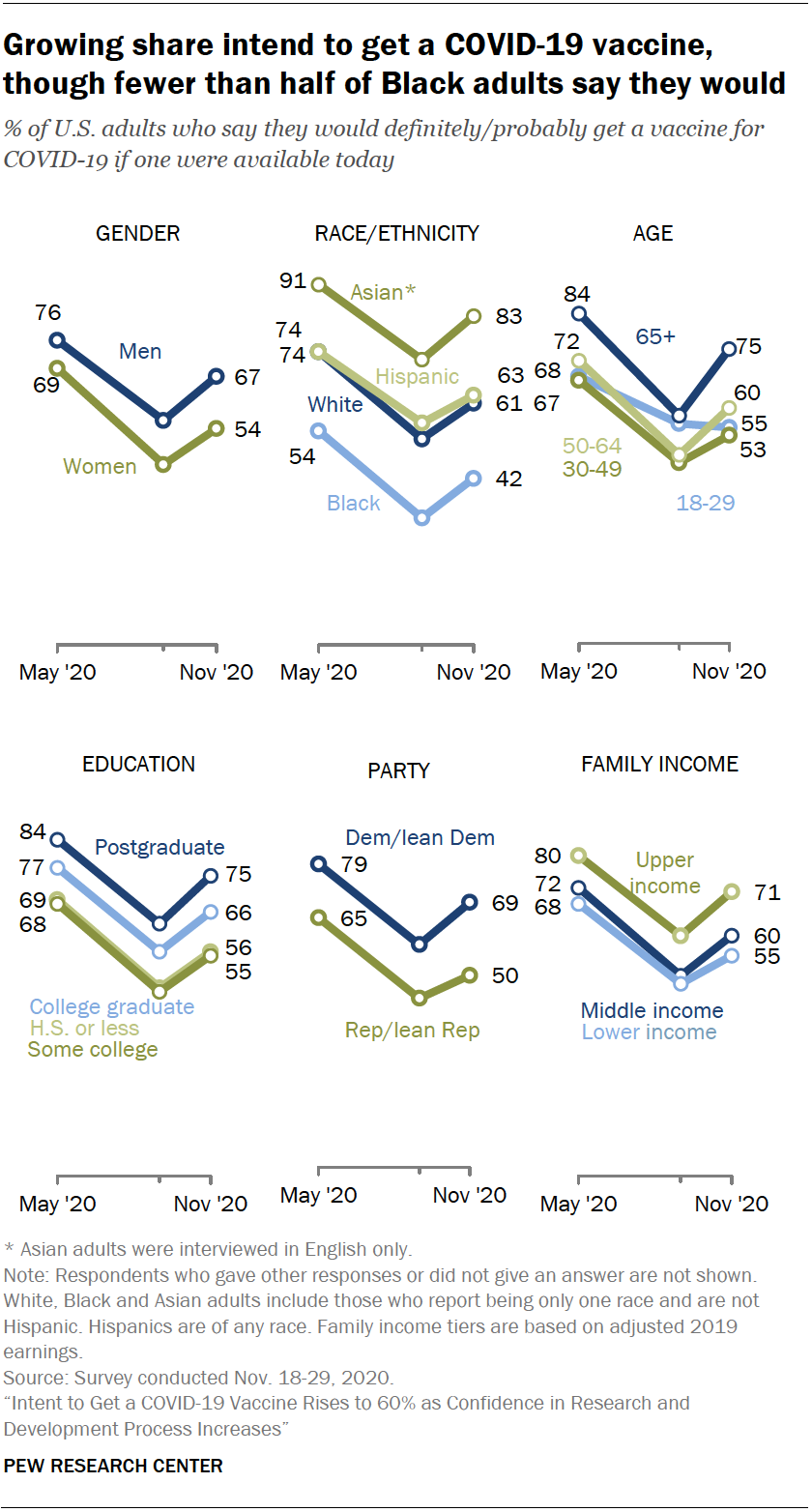

Partisanship plays a role in many of these beliefs and practices. Overall, there’s a 19-point gap between the shares of Democrats and those who lean to the Democratic Party (69%) and Republicans and Republican leaners (50%) who currently say they would get vaccinated for the coronavirus.

These are among the principal findings from the Pew Research Center’s latest report on the coronavirus outbreak and Americans’ views of a COVID-19 vaccine. The survey also finds:

Most are ‘bothered’ when people around them in public do not wear masks; few are bothered by stores that require face-coverings. About seven-in-ten (72%) say it bothers them a lot or some when people around them in public do not wear masks. Far fewer (28%) say it bothers them at least some when stores require customers to wear a mask for service.

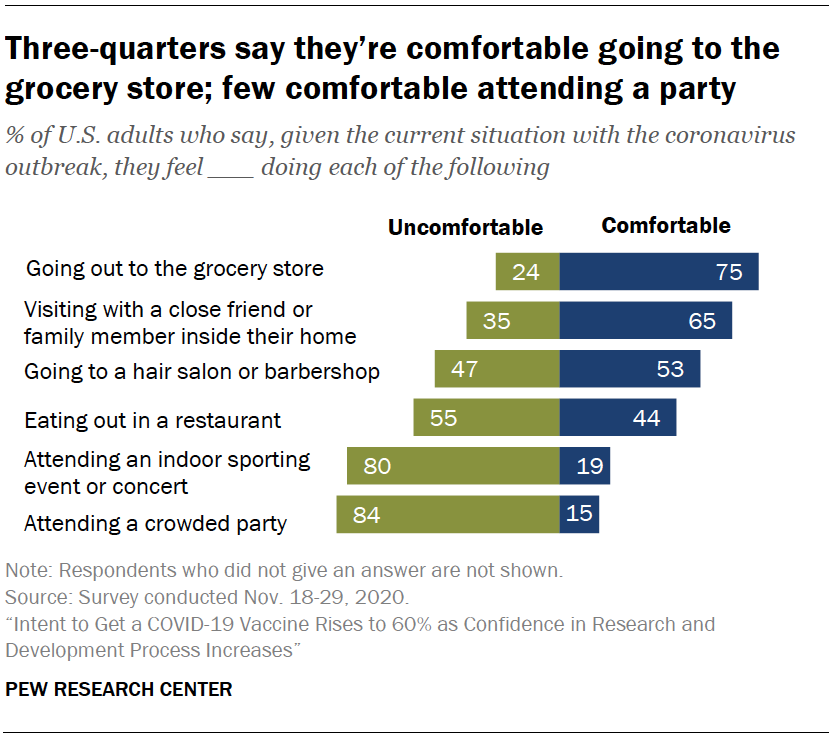

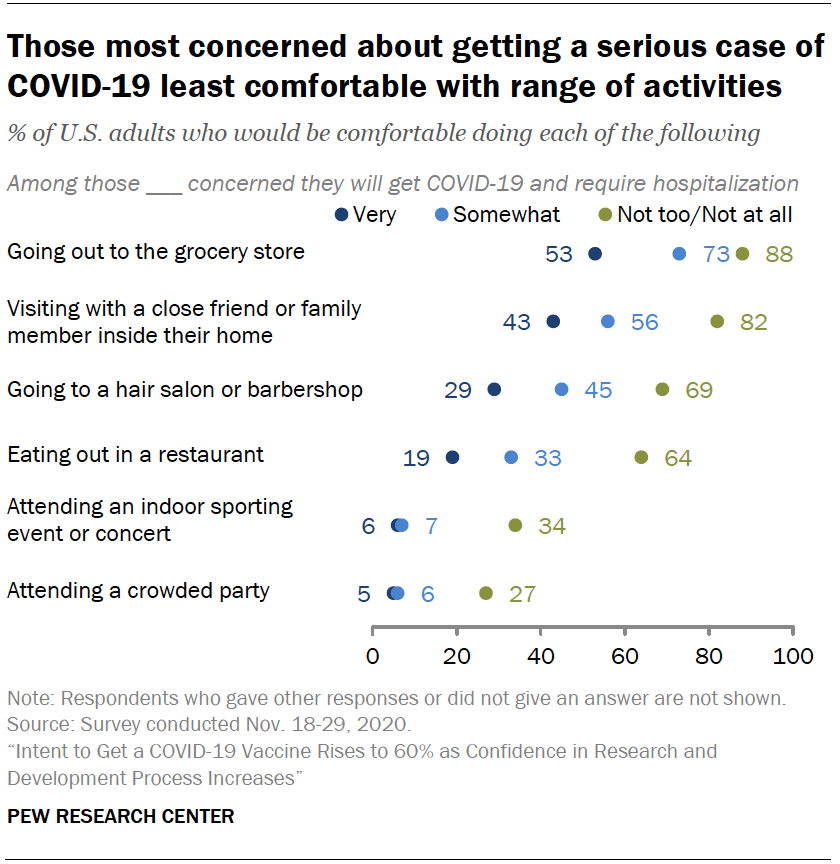

Americans comfortable going to the grocery but not a crowded party. Three-quarters of adults say they’re comfortable going to the grocery store given the current situation with the coronavirus, but views are more mixed when it comes to a restaurant or hair salon, and most would be uncomfortable attending a crowded party. One key factor tied to people’s comfort level is a personal concern with contracting a serious case of COVID-19: Those most concerned are the least comfortable going out.

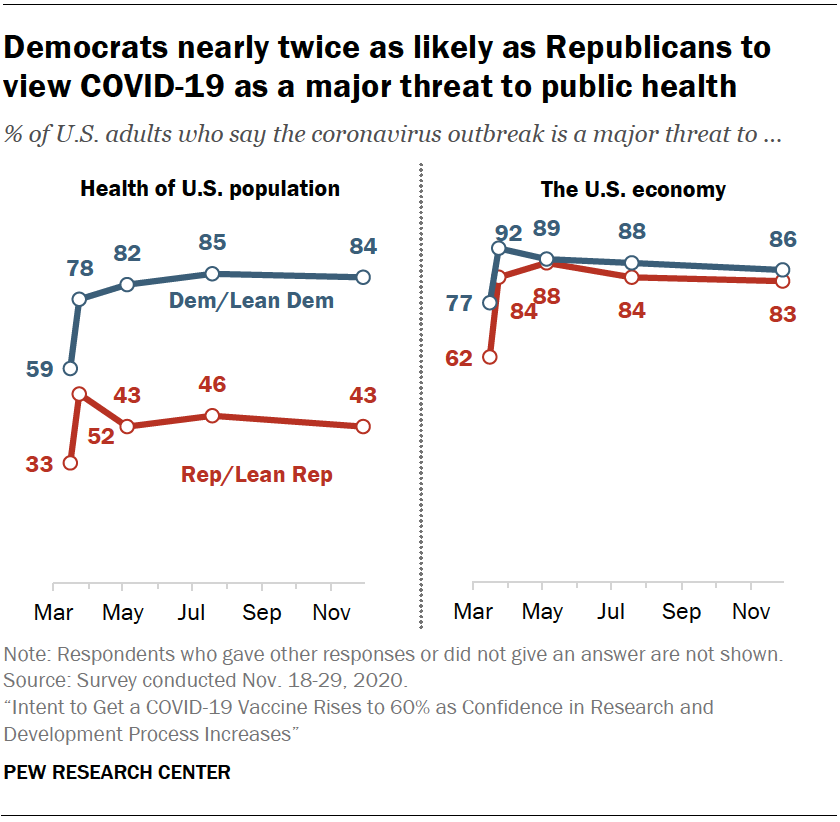

Republicans remain less likely than Democrats to see outbreak as major threat to public health. Overall, 84% of Democrats and 43% of Republicans say the coronavirus outbreak is a major threat to the U.S. population as a whole. The partisan gap on this measure remains about as wide as at any point during the outbreak and stands in contrast to the large shares of both Republicans (83%) and Democrats (86%) who say the outbreak is a major threat to the U.S. economy.

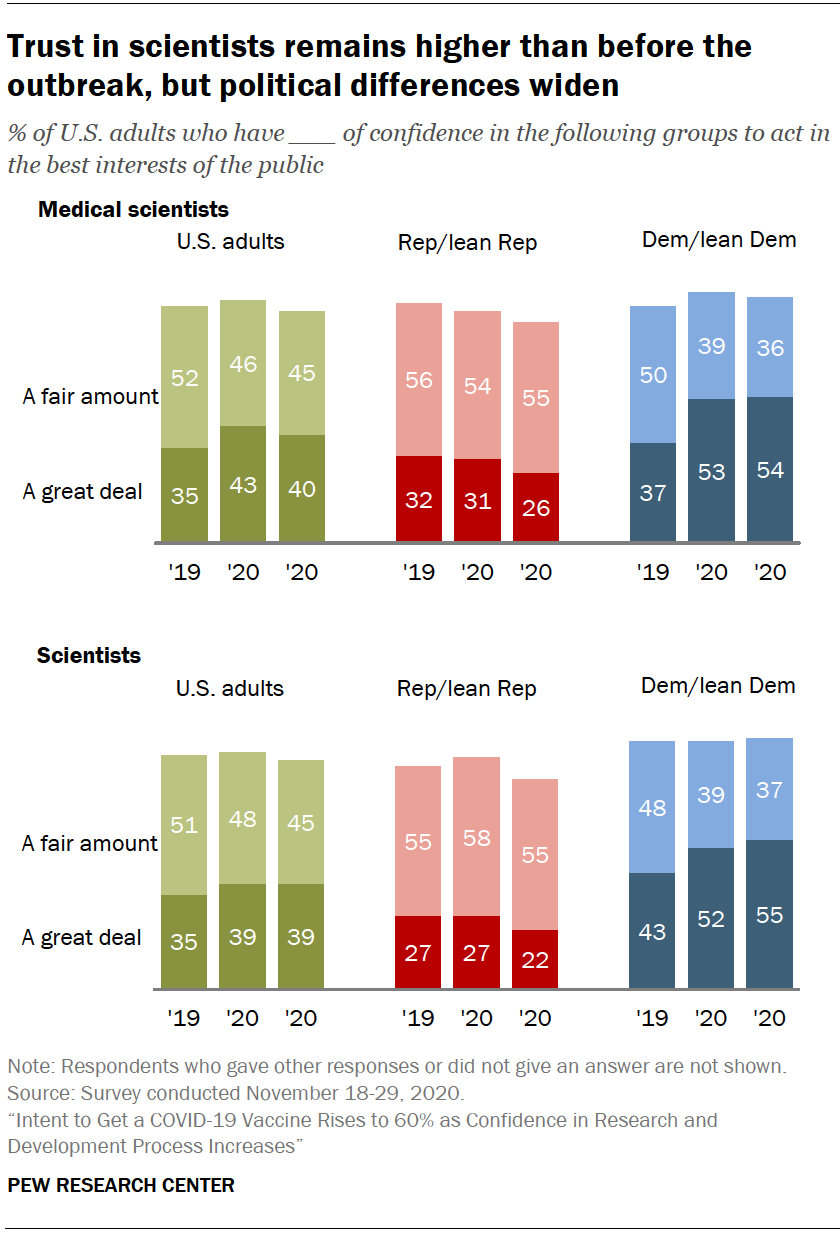

Confidence in scientists remains slightly higher than before the pandemic. With scientists and their work in the spotlight, 39% of Americans say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest, an uptick from 35% who said this before the pandemic took hold. Most Americans have at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists. However, ratings of scientists are now more partisan than at any point since Pew Research Center first asked this question in 2016: 55% of Democrats now say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists, compared with just 22% of Republicans who say the same.

Intention to be vaccinated for COVID-19 rises across the board

Six-in-ten Americans say they would definitely or probably get a coronavirus vaccine if it were available today, up 9 percentage points from 51% in September.

Six-in-ten Americans say they would definitely or probably get a coronavirus vaccine if it were available today, up 9 percentage points from 51% in September.

While the uptick in intent to get a vaccine for COVID-19 has been broad based, there remain sizable differences among key demographic groups.

Black Americans continue to stand out as less inclined to get vaccinated than other racial and ethnic groups: 42% would do so, compared with 63% of Hispanic and 61% of White adults. English-speaking Asian Americans are even more likely to say they would definitely or probably get vaccinated (83%).

The coronavirus is thought to be a particular health risk for older adults, who are more likely to have complicating preexisting conditions and weaker immune systems to combat the disease. Three-quarters of adults ages 65 and older say they would definitely or probably get vaccinated, compared with 55% of those under age 30.

Those with higher family incomes, adjusted for cost of living and household size, are more likely than those with middle or lower incomes to say they would get immunized. (See the Appendix for more on these and other groups’ intentions to get a coronavirus vaccine.)

Those with higher family incomes, adjusted for cost of living and household size, are more likely than those with middle or lower incomes to say they would get immunized. (See the Appendix for more on these and other groups’ intentions to get a coronavirus vaccine.)

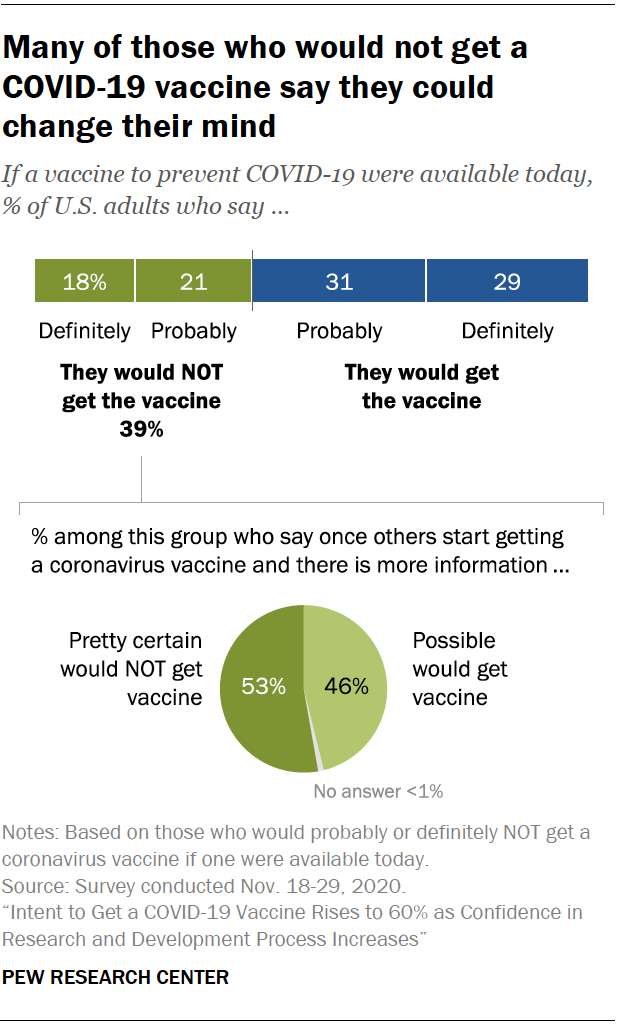

People’s views on getting a coronavirus vaccine that is not yet available to the general public remain fluid. Among the roughly four-in-ten Americans who say they would not get the vaccine today, 46% says it’s possible they would do so once others start getting vaccinated and more information becomes available. Still, 53% of those not currently planning to get vaccinated (21% of all Americans) say they are pretty certain that they won’t get a vaccine even with more information.

Regardless of people’s intention to get vaccinated, 62% of Americans report they would be uncomfortable being among the first to do so. Roughly two-thirds of those who say they would “probably” be vaccinated are uncomfortable being among the first as are nearly all of those who say they would not be vaccinated if a vaccine were available today. The exception comes from the roughly three-in-ten U.S. adults (29%) who say they would definitely be vaccinated; 82% of this group say they would be comfortable being in the first groups to be immunized against coronavirus.

Regardless of people’s intention to get vaccinated, 62% of Americans report they would be uncomfortable being among the first to do so. Roughly two-thirds of those who say they would “probably” be vaccinated are uncomfortable being among the first as are nearly all of those who say they would not be vaccinated if a vaccine were available today. The exception comes from the roughly three-in-ten U.S. adults (29%) who say they would definitely be vaccinated; 82% of this group say they would be comfortable being in the first groups to be immunized against coronavirus.

Those who would not get a coronavirus vaccine are skeptical of the vaccine R&D process and have less personal concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19

A key question for public health going forward is whether enough Americans will be immunized against the coronavirus to bring collective health benefits known as herd immunity. As of now, it is unclear what threshold will be needed to slow the spread of the coronavirus. The threshold of immunization is specific to each disease, ranging between roughly 70% and 90% of the population.

A key question for public health going forward is whether enough Americans will be immunized against the coronavirus to bring collective health benefits known as herd immunity. As of now, it is unclear what threshold will be needed to slow the spread of the coronavirus. The threshold of immunization is specific to each disease, ranging between roughly 70% and 90% of the population.

About four-in-ten Americans (39%) say they would likely opt out of a coronavirus vaccine.

One factor in people’s intention to be vaccinated is their assessment of their own need for the vaccine. About half of Americans who see themselves as being at little or no risk of getting a case of COVID-19 that would require hospitalization say they would not get vaccinated (52%).

Public confidence in the vaccine development process also plays a role in people’s intention to be vaccinated. The share of Americans with a great deal of confidence in the research and development process for a coronavirus vaccine has gone up in tandem with the share of those who say they would be vaccinated. In the latest Center survey, three-in-ten (30%) have a great deal of confidence in the R&D process, up from 19% in September; three-quarters of Americans now have at least a fair amount of confidence in the process.

But the roughly quarter of Americans with little or no confidence in this process are disinclined to be vaccinated against COVID-19. In this group, 19% say they would get vaccinated, while 80% would not.

People’s habits and practices related to the seasonal flu vaccine also link with their intention to be vaccinated against the coronavirus. Nearly eight-in-ten Americans (78%) who have received a flu shot so far this season, say they would get a coronavirus vaccine, as do most of those who say they typically get a flu shot each year (77%). By contrast, 61% of Americans who report that they rarely or never get the seasonal flu vaccine say they would pass on a coronavirus vaccine if it were available today.

Divide over mask wearing, comfort with activities align with people’s degree of concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19

Level of concern over getting a serious case of the coronavirus is tied to a range of other views about the outbreak, including attitudes about others not wearing masks in public and comfort with a variety of activities, such as eating out at a restaurant.

Level of concern over getting a serious case of the coronavirus is tied to a range of other views about the outbreak, including attitudes about others not wearing masks in public and comfort with a variety of activities, such as eating out at a restaurant.

Overall, slightly more than half of Americans say they are very (23%) or somewhat (30%) concerned that they will get the coronavirus and require hospitalization; 47% say they are not too or not at all concerned about this.

Personal concern about getting a serious case of COVID-19 is lower among White adults than those in other racial and ethnic groups. Personal concern is also lower among adults ages 18 to 29 than those in older age groups.

Three-in-ten of those with lower family incomes say they are very concerned about getting a case of COVID-19 that would require hospitalization. People with lower family incomes are more worried about getting a serious case of COVID-19 than those in middle- or upper-income tiers.

Personal concern about getting the coronavirus also is linked with partisanship. A majority (66%) of Democrats say they are very (30%) or somewhat (36%) concerned about getting a serious case of COVID-19. Some 37% of Republicans say they are very or somewhat concerned about getting the coronavirus and requiring hospitalization, while 62% say they are not too or not at all concerned about this.

Wearing a mask or face covering is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is one of the most visible steps people have taken to limit the spread of the disease.

Wearing a mask or face covering is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is one of the most visible steps people have taken to limit the spread of the disease.

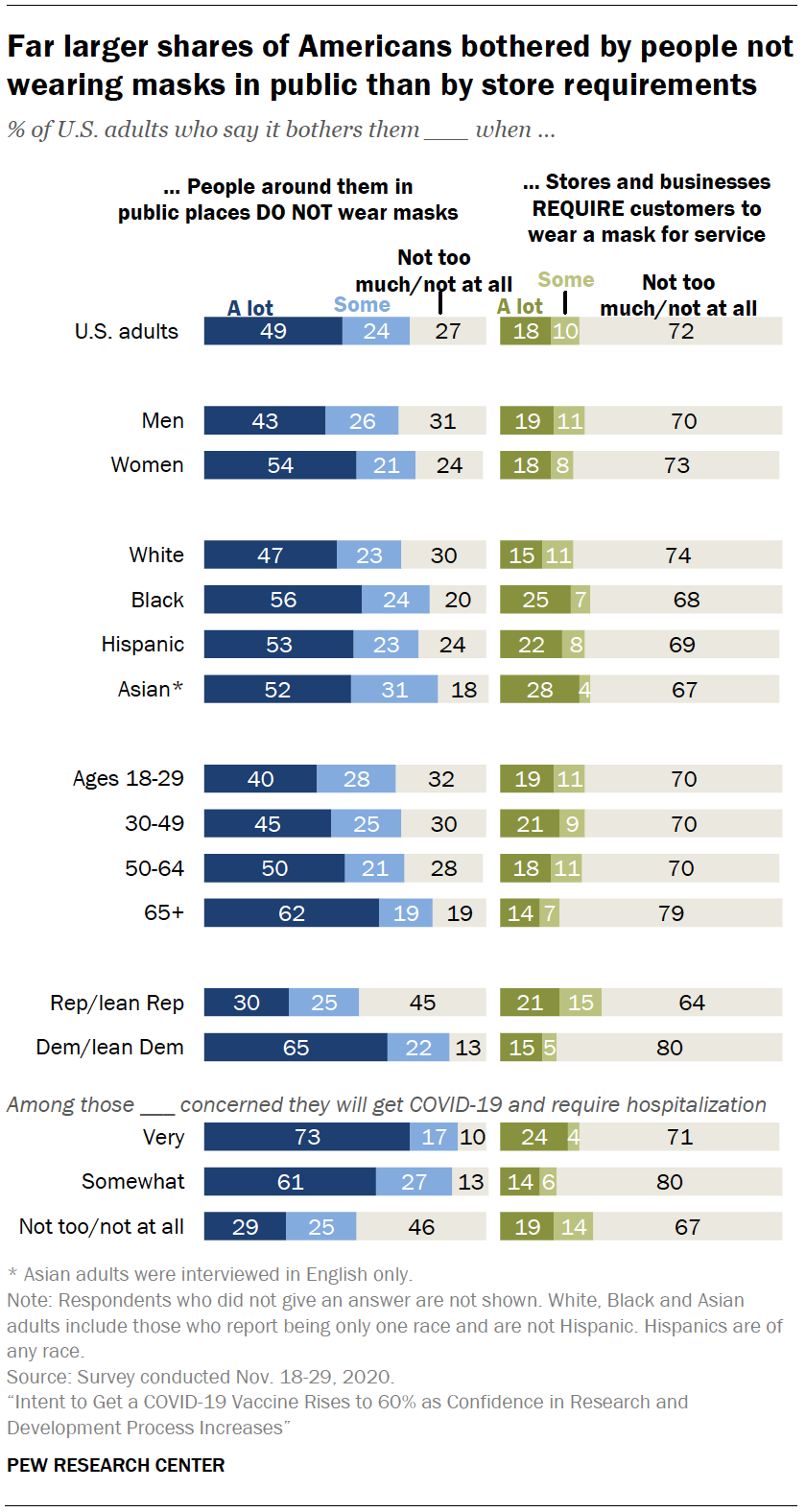

Americans are much more likely to say they are bothered by people not wearing masks in public than by stores and businesses requiring masks for service.

About seven-in-ten Americans (72%) say they are bothered a lot (49%) or some (24%) when they are around people in public places who are not wearing masks. By contrast, just 28% say they are bothered at least some by stores and businesses that require customers to wear a mask. Far more (72%) say such a requirement does not bother them much or at all.

Those who are very (73%) or somewhat (61%) concerned about getting a serious case of COVID-19 are far more likely to say it bothers them a lot when people around them do not wear masks than those who are not too or not at all concerned about getting the coronavirus (29%).

Similarly, adults ages 65 and older (62%) along with Democrats (65%) are more likely to say they are bothered a lot when people around them do not wear masks in public.

Similarly, adults ages 65 and older (62%) along with Democrats (65%) are more likely to say they are bothered a lot when people around them do not wear masks in public.

Majorities across all major demographic groups say they are not too or not at all bothered by stores and businesses requiring a face-covering. Republicans are relatively more likely to say they are bothered by this than Democrats. Still, just 36% of Republicans are bothered a lot or some by such requirements, compared with 64% who say the requirements don’t bother them much or at all.

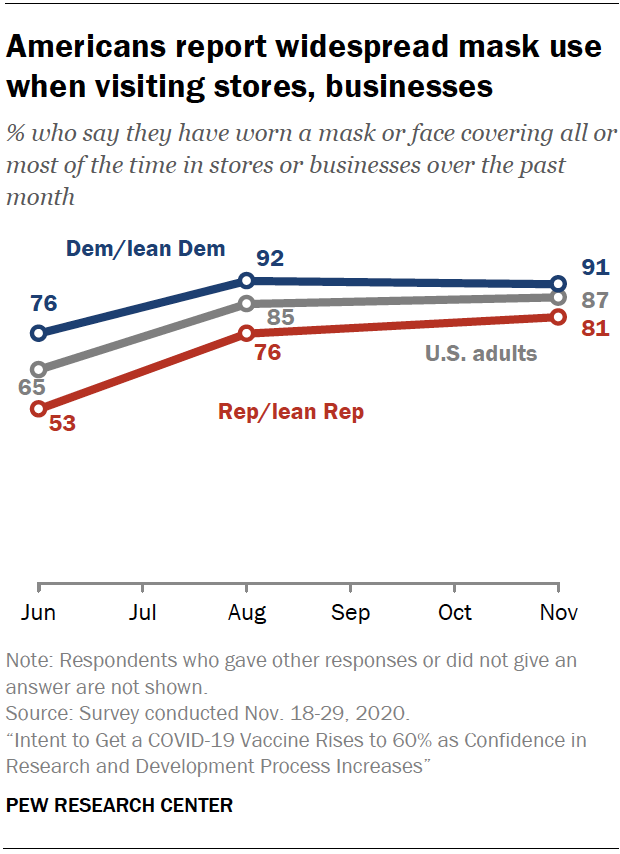

Large shares of Americans across groups report wearing a mask when out in public. Nearly nine-in-ten (87%) adults say they have worn a mask or face covering all or most of the time when in stores and businesses over the past month, including 91% of Democrats and 81% of Republicans. While a slightly larger majority of Democrats than Republicans reports wearing a mask in stores, the partisan gap is much smaller than it was in June (23 points).

Americans draw clear distinctions between the activities they feel comfortable and uncomfortable doing during the outbreak.

Americans draw clear distinctions between the activities they feel comfortable and uncomfortable doing during the outbreak.

A majority (75%) says they feel comfortable going to the grocery store given the current situation with the coronavirus outbreak, and about two-thirds (65%) say they are comfortable visiting with a close friend or family member inside their home. Just over half (53%) are comfortable going to a hair salon or barbershop.

By contrast, more say they would be uncomfortable eating in a restaurant than say they would be comfortable (55% vs. 44%), and large majorities would be uncomfortable attending an indoor sporting event or concert (80%) or attending a crowded party (84%).

People’s degree of personal concern over getting a serious case of COVID-19 is strongly linked with their comfort level with a range of activities.

People’s degree of personal concern over getting a serious case of COVID-19 is strongly linked with their comfort level with a range of activities.

For instance, 53% of those who are very concerned about getting a serious case of the coronavirus say they are comfortable going to the grocery store compared with far larger shares of those who are somewhat concerned (73%) or not too or not at all concerned about getting a serious case of the coronavirus (88%).

Other activities illustrate a similar pattern, including visiting with a close friend or family member in their home and going to a hair salon or barbershop.

Other activities illustrate a similar pattern, including visiting with a close friend or family member in their home and going to a hair salon or barbershop.

Reflecting the mounting toll the coronavirus has had on the country, just over half of Americans (54%) now say they personally know someone who has been hospitalized or has died as a result of having COVID-19. The share who say this has risen in each Pew Research Center survey conducted since April.

Black Americans are especially likely to say they know someone who has been hospitalized or died as a result of having the coronavirus: 71% say this, compared with smaller shares of Hispanic (61%), White (49%) and Asian American (48%) adults.

Republicans and Democrats differ over outbreak’s threat to public health

A large majority of Americans (84%) continue to view the coronavirus outbreak as a major threat to the U.S economy, and about two-thirds (65%) view it as a major threat to the health of the U.S. population as a whole. Public concern about the outbreak’s impact on the economy and public health have held steady in surveys conducted since late March.

A large majority of Americans (84%) continue to view the coronavirus outbreak as a major threat to the U.S economy, and about two-thirds (65%) view it as a major threat to the health of the U.S. population as a whole. Public concern about the outbreak’s impact on the economy and public health have held steady in surveys conducted since late March.

Democrats remain far more likely than Republicans to say the outbreak is a major threat to public health: 84% of Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party say this, compared with 43% of Republicans and Republican leaners. The partisan gap on this question remains about as wide as it has been at any point during the outbreak.

By contrast, large shares of both Democrats (86%) and Republicans (83%) say the outbreak is a major threat to the U.S. economy, consistent with Center surveys conducted over the past seven months.

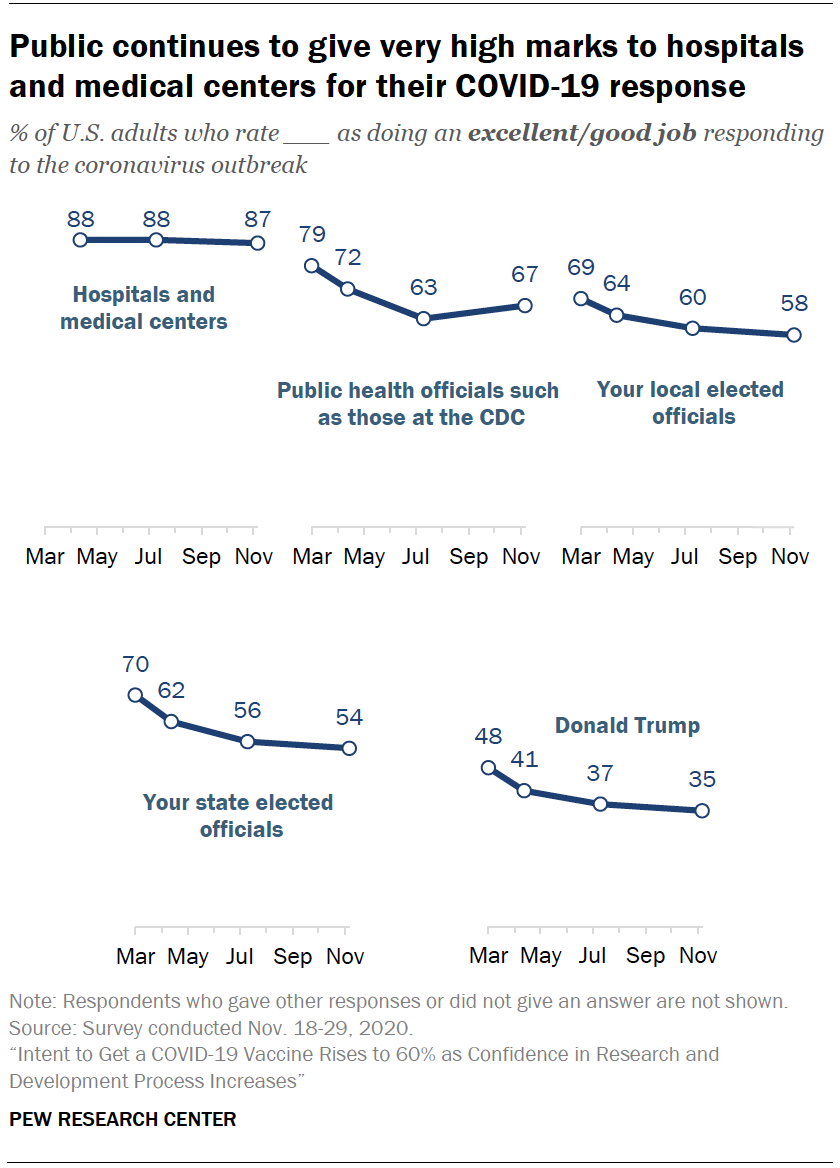

When it comes to how key groups and officials have responded to the outbreak, the public continues to rate the job done by hospitals and medical centers very highly. Nearly nine-in-ten (87%) say they have done an excellent or good job responding to the outbreak.

When it comes to how key groups and officials have responded to the outbreak, the public continues to rate the job done by hospitals and medical centers very highly. Nearly nine-in-ten (87%) say they have done an excellent or good job responding to the outbreak.

About two-thirds (67%) say public health officials, such as those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have done an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak. This rating is slightly higher than last assessed in July. Narrow majorities rate the responses by local (58%) and state elected officials (54%) positively; both groups have seen their ratings decline since the early stages of the outbreak in the U.S.

The public is largely critical of how President Donald Trump has responded. More say Trump has done an only fair or poor job than say he has done an excellent or good job (65% vs. 36%) responding to the outbreak. Ratings of Trump are similar to those from July.

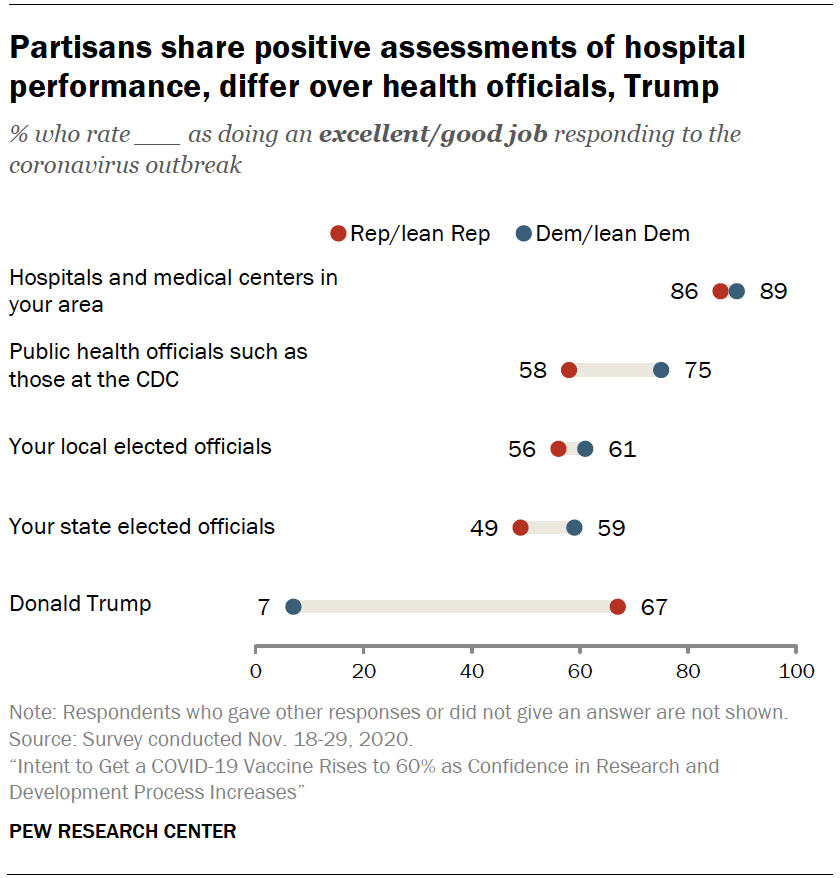

Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say Trump has done an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak (67% vs. 7%). Still, Trump’s ratings among Republicans have moved lower over the course of the outbreak: 83% rated his performance positively in late March and 73% said the same in late July.

Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say Trump has done an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak (67% vs. 7%). Still, Trump’s ratings among Republicans have moved lower over the course of the outbreak: 83% rated his performance positively in late March and 73% said the same in late July.

A larger majority of Democrats (75%) than Republicans (58%) say public health officials have done an excellent or good job responding to coronavirus outbreak. Democrats’ ratings of health officials have been consistently high in surveys since March, while Republicans’ ratings have been lower in comparison.

Partisans are aligned in their highly positive ratings of the response by hospitals and medical centers: 89% of Democrats and 86% of Republicans say they have done an excellent or good job responding to the outbreak.

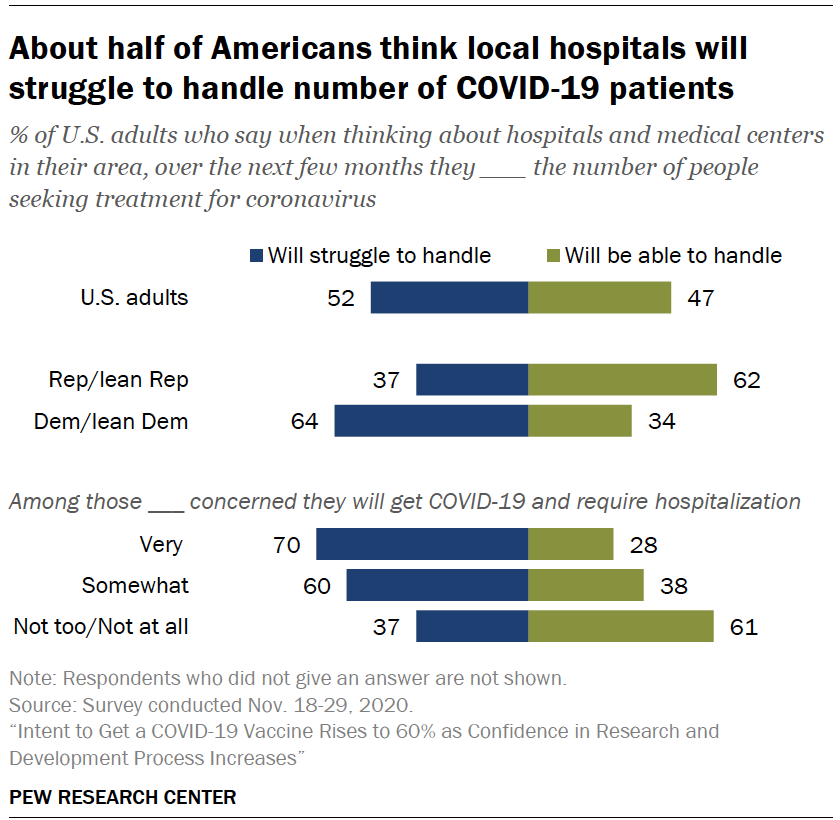

Though most give positive marks to hospitals and medical centers for their handling of the outbreak, 52% of U.S. adults think the hospitals in their area will struggle to handle the number of people seeking treatment for the coronavirus over the next few months; 47% think they will be able to handle the number of patients.

Though most give positive marks to hospitals and medical centers for their handling of the outbreak, 52% of U.S. adults think the hospitals in their area will struggle to handle the number of people seeking treatment for the coronavirus over the next few months; 47% think they will be able to handle the number of patients.

Republicans are less concerned than Democrats that hospitals will struggle to handle coronavirus caseloads, a finding in keeping with wide political differences over the degree to which the coronavirus poses a major threat to public health.

Seven-in-ten of those who are very concerned about getting a case of COVID-19 that would require hospitalization believe hospitals in their area will struggle to handle patient needs over the next few months.

Seven-in-ten of those who are very concerned about getting a case of COVID-19 that would require hospitalization believe hospitals in their area will struggle to handle patient needs over the next few months.

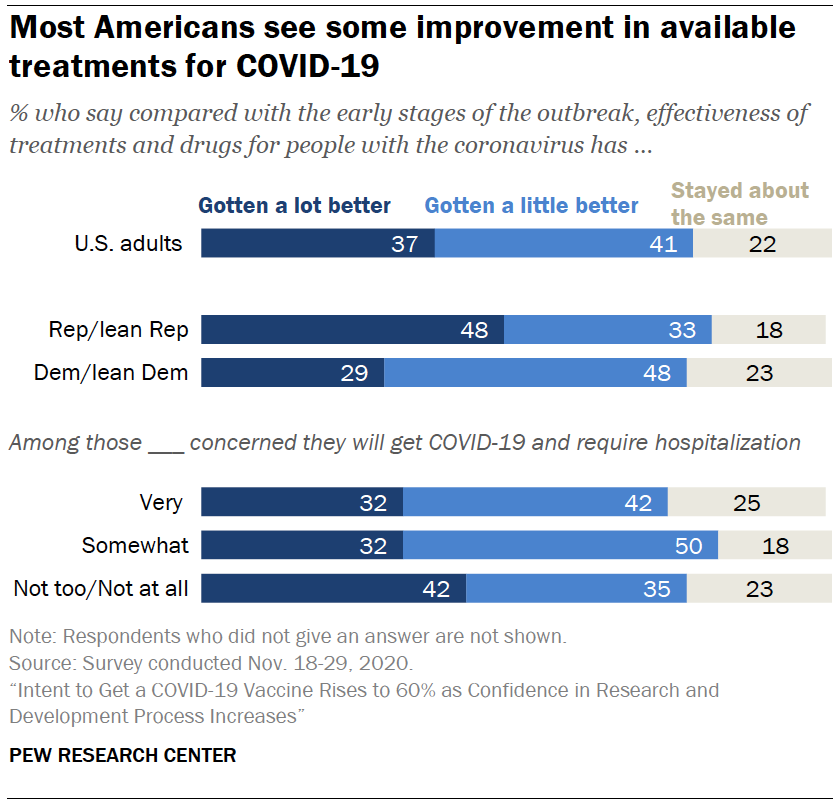

Americans think the effectiveness of treatments for the coronavirus have improved since the early stages of the outbreak: Nearly eight-in-ten (78%) say treatments and drugs for people with COVID-19 have gotten a lot (37%) or a little (41%) better.

There are growing political divides over trust in scientists since the start of the coronavirus outbreak

Amid a global crisis that puts scientists and their work in a central role advising government leaders on measures to address the spread of the coronavirus and leading efforts to develop new treatments and a vaccine to prevent it, the Center finds public confidence in scientists stable since last measured in April and thus modestly higher than before the outbreak fully took hold.

About four-in-ten (39%) U.S. adults say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest, the same as in April and up from 35% in January 2019.

About four-in-ten (39%) U.S. adults say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest, the same as in April and up from 35% in January 2019.

Similarly, four-in-ten U.S. adults (40%) say they have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interest, compared with 35% who said this before the pandemic and roughly the same as in April 2020. (Half of survey respondents were randomly assigned to rate their confidence in medical scientists and half to rate their confidence in scientists).

Large shares of the U.S. public have at least a fair amount of confidence in both groups to act in the best interests of the public. Very few say they have not too much or no confidence at all in scientists or medical scientists (15% and 14%, respectively).

But these generally positive overall levels of trust in scientists are not universally shared among Americans. Democrats’ trust in scientists has risen since January 2019 while that of Republicans has dropped modestly over the same time period. As a result, political differences over this assessment have widened.

In the new survey, 55% of Democrats and those who lean to the Democratic Party say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists, roughly the same as in April and up from 43% in January 2019. The share of Republicans with this strongest level of confidence in scientists to act in the public interest has gone down over the same time period, from 27% in January 2019 and April 2020 to 22% in the new survey. Democrats are now 33 percentage points more likely than Republicans to say they have a great deal of confidence in scientists, a partisan gap that is much larger than it was in January of 2019 (16 points). When the Center first measured public confidence in scientists in June 2016, Democrats were 11 points more likely than Republicans to express a great deal of confidence in scientists.

There is now a similarly large partisan divide in confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interest, in contrast with public assessments before the coronavirus outbreak. In the new survey, 54% of Democrats including leaners have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the best interests of the public, about the same as in April (53%) and up from 37% in January 2019. Among Republicans and Republican leaners, 26% have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists, down slightly since April, when 31% said this. The partisan gap in this assessment is now 28 percentage points, up from a statistically nonsignificant 5 percentage points before the coronavirus outbreak spread widely in the U.S.

There are also long-standing differences across racial and ethnic groups when it comes to trust in scientists and medical scientists to act in the best interests of the public. For example, White Americans (43%) are more likely than either Black (33%) or Hispanic (30%) Americans to say they have a great deal of confidence in medical scientists. (See Appendix for details.)

Public trust in scientists and medical scientists is roughly on par with trust in the military. About four-in-ten U.S. adults (39%) have a great deal of confidence in the military to act in the public interest, 44% have a fair amount of confidence in the military and just 17% have not too much or no confidence in the military at all. Republicans remain more likely than Democrats to hold a high level of trust in the military (51% vs. 28%).

Public trust in scientists and medical scientists is roughly on par with trust in the military. About four-in-ten U.S. adults (39%) have a great deal of confidence in the military to act in the public interest, 44% have a fair amount of confidence in the military and just 17% have not too much or no confidence in the military at all. Republicans remain more likely than Democrats to hold a high level of trust in the military (51% vs. 28%).

Public confidence in other groups is far lower. About two-in-ten U.S. adults (21%) have a great deal of confidence in K-12 public school principals, down from 28% in April but on par with January 2019.

The uptick in public confidence for scientists (as well as for medical scientists) since January 2019 is not seen in ratings of other groups and institutions. For instance, the shares with the strongest level of confidence in the military and religious leaders has stayed about the same since January of 2019, and strong confidence in elected officials remains mired in the single digits. The public is less likely to say they have a great deal of confidence in journalists today than they were in December 2018 (9% vs. 15%) and assessments are the same now as they were in April.