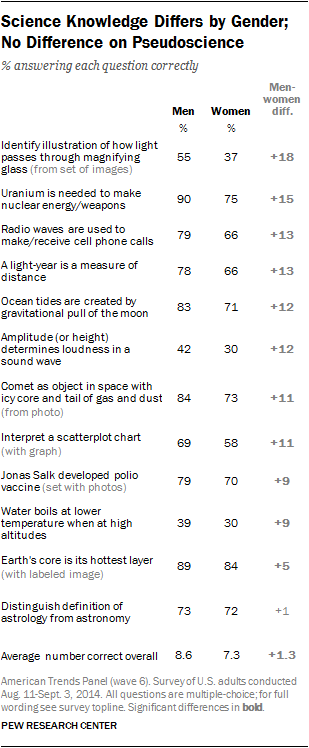

Men tend to answer more of these science knowledge questions correctly than do women, the new Pew Research Center survey found. Men score an average of 8.6 out of 12 correct answers, compared with women’s 7.3 correct answers.

Men tend to answer more of these science knowledge questions correctly than do women, the new Pew Research Center survey found. Men score an average of 8.6 out of 12 correct answers, compared with women’s 7.3 correct answers.

Some 24% of women answer 10 or more questions correctly, compared with 43% of men who did this. And 69% of men get at least eight of the questions right, compared with 51% of women.

The largest difference between men and women occurs on a question asking respondents to select from a set of four images that illustrate what happens to light when it passes through a magnifying glass. Some 55% of men and 37% of women identify the correct image showing the lines crossing after they pass through a magnifying glass, a difference of 18 percentage points. There was also a 15-point difference between the sexes on knowledge about one topic commonly discussed in world news and foreign policy: While three-quarters of women (75%) correctly identify uranium as an element needed to make nuclear energy and nuclear weapons, nine-in-ten men answer this correctly.

Men (73%) and women (72%) are equally likely to identify the definition of astrology from a set of four options, however. And on the question about which layer of the Earth is hottest, there are only modest differences, with 89% of men and 84% of women selecting the correct response.

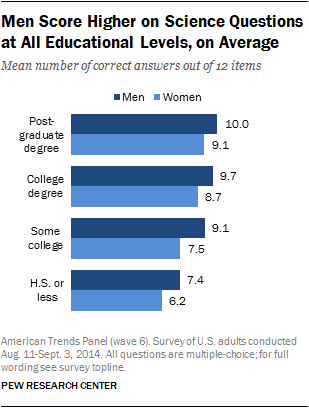

Education differences between men and women, particularly among older generations of adults, may explain some of these gendered patterns in science knowledge. For example, men and women who hold a postgraduate degree are about equally likely to correctly interpret a scatterplot chart and to know that ocean tides are influenced by the gravitational pull of the moon. But, on average, men tend to know more of the answers to these science questions than do women, even when controlling for each of four levels of education.

Education differences between men and women, particularly among older generations of adults, may explain some of these gendered patterns in science knowledge. For example, men and women who hold a postgraduate degree are about equally likely to correctly interpret a scatterplot chart and to know that ocean tides are influenced by the gravitational pull of the moon. But, on average, men tend to know more of the answers to these science questions than do women, even when controlling for each of four levels of education.

According to government research on issues of science knowledge, males and females tend to differ in their expressed interest in science topics and in their course selection at the high school, college and postgraduate levels. Men, on average, express greater interest in the physical sciences than women. This could in part explain the tendency for men to know the right answers to more of these questions, which focus mostly on the physical sciences, than women, even when controlling for educational level.13 The U.S. government’s Science and Engineering Indicators 2014 report shows that women and men tend to score about equally high on factual knowledge items in the biological sciences, while men tend to score higher on scales of factual knowledge in the physical sciences.14

Pew Research Center surveys have included only a handful of biological science knowledge questions over the years. As detailed in a later section, on four questions related to health and biomedical issues in the news, there were no differences or only modest differences between men and women. And, on two other questions that tie more closely to the kinds of knowledge taught in school, women (59%) were more likely than men (49%) to know that antibiotics will not kill viruses, according to a 2009 Pew Research survey. However, a 2014 Pew Research survey found men (80%) more likely than women (73%) to correctly identify the main function of red blood cells.

In addition, the questions on the Pew Research survey ask for knowledge or applications of scientific principles, such as the definition of a light-year or the principles underlying sound, rather than questions designed to measure understanding of scientific processes or methods used to test scientific theories. The Science and Engineering Indicators report found no difference between adult men and women on measures designed to tap understanding of probabilities, experiments, or a basic understanding of the scientific method.15 Previous Pew Research surveys have included only one question measuring understanding of scientific processes. On that question, women (78%) were slightly more likely than men (72%) to identify comparison groups as a better way to study the effectiveness of a drug treatment than a single treatment group.

Quiz: Test your science knowledge

Quiz: Test your science knowledge