For the most part, Black Americans express positive views of medical researchers. About eight-in-ten have at least a fair amount of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public’s interests. And, on balance, Black Americans express trust in medical researchers’ competence to do a good job.

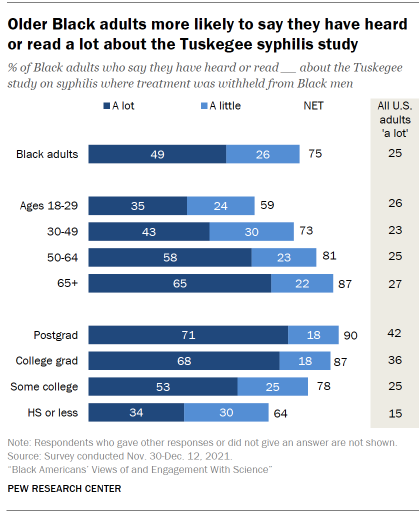

Still, there are ongoing concerns about the potential for research misconduct and accountability. Most Black Americans are familiar with the legacy of past research abuses. Three-quarters of Black Americans know at least a little about the Tuskegee syphilis study, a study conducted by the federal government in which treatment was withheld from Black men.

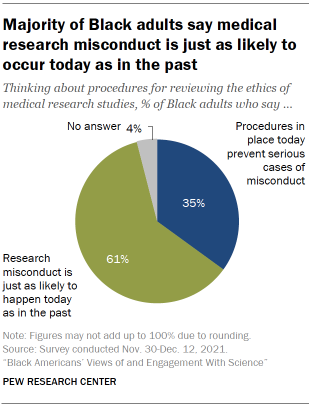

And a majority of Black adults (61%) say that research misconduct is just as likely to occur today as it was in the past; far fewer (35%) say there are procedures in place today that will prevent serious cases of misconduct.

Most Black Americans are also skeptical of medical researchers when it comes to issues of openness and accountability. Small shares say that medical researchers regularly face serious consequences for research misdeeds or admit and take responsibility for mistakes when they occur.

Familiarity with the work of medical researchers is a major factor shaping Black adults’ views of medical researchers: Those who say they know more about what they do tend to be more positive in their assessments of these researchers.

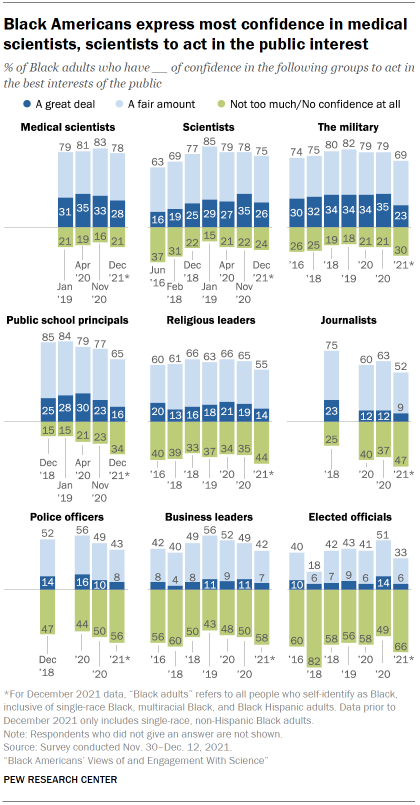

Large majorities of Black adults have at least some trust in medical scientists or scientists, generally

Black Americans have largely positive ratings of medical scientists and scientists, compared with other prominent groups and institutions in society.

About eight-in-ten Black Americans (78%) have at least a fair amount of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public’s interests, including 28% who say they have a great deal of confidence in them.

Ratings of scientists are similar; 26% have the strongest level of trust and three-quarters have at least some trust in scientists. (Half of the survey respondents were asked to rate their confidence in medical scientists, while half were asked about scientists.)

Black Americans express less confidence in other groups: 69% say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in the military and 65% say this about K-12 public school principals.

Slightly more than half of Black adults (55%) have at least a fair amount of confidence in religious leaders to act in the public’s interests, while 44% say they have not too much or no confidence in them. Black Christians are about twice as likely as religiously unaffiliated Black adults to express positive ratings of religious leaders (66% vs. 32%).

Ratings of business leaders and police officers are among the lowest of the nine groups included in the survey. About four-in-ten Black adults (43%) have at least a fair amount of confidence in police officers to act in the public’s best interests, while a 56% majority has not too much or no confidence in them. The balance of confidence in views of business leaders is similar (42% have at least a fair amount of confidence, while 58% have not too much or no confidence at all).

Black adults’ trust in many of these nine groups and institutions declined in the last year, mirroring similar declines among the general public. For example, Black adults’ trust in K-12 public school principals has fallen 12 percentage points and trust in journalists is down 11 points.

Confidence in scientists and medical scientists also declined since November 2020. The share of Black adults with a great deal of confidence in scientists dropped from 35% to 26% (nine points); confidence in medical scientists dipped slightly from 33% to 28%.6

While trust in medical scientists has fallen across most demographic groups, the decline among White adults has been especially pronounced. As a result, there is now little difference between how White, Black and Hispanic adults see medical scientists. This is a shift from previous Pew Research Center surveys, where White adults were more likely than Black adults to express high levels of confidence in medical scientists.

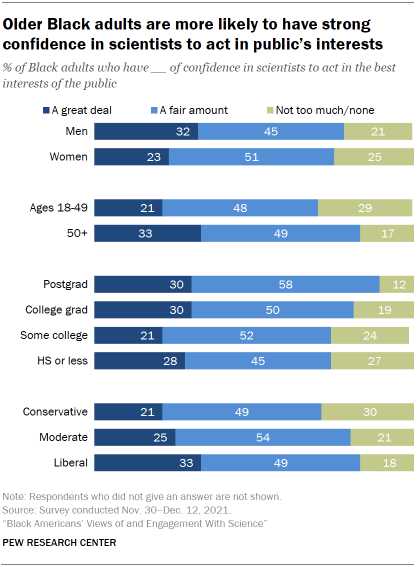

Older Black adults express more trust in scientists to act in the public’s interests

Older Black adults express higher levels of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests than do younger Black adults.

Most Black adults ages 65 and older (87%) have at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists, including 37% who have a great deal of confidence in them.

Younger Black adults rate scientists less favorably. Roughly seven-in-ten Black adults ages 18 to 49 (69%) have at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists, while 29% say they have not too much or no confidence in scientists to act in the public’s interests.

Black men and those who describe their political ideology as liberal are more inclined to rate scientists positively.7 Black college graduates are modestly more likely to have positive assessments of scientists compared with those with some college or less education.

There are similar patterns by age, gender, ideology and education in ratings of medical scientists.

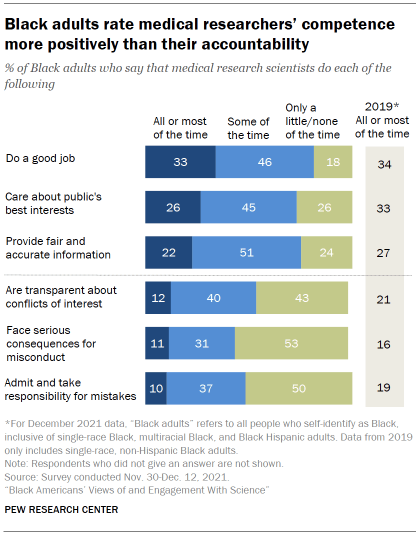

Black Americans generally hold positive views of medical researchers’ competence, skeptical of whether they own up to mistakes

People’s trust in scientists and other groups are often thought to vary across dimensions of their behavior. The survey included ratings of trust in medical research scientists when it comes to competence, caring for others’ interests, and the trustworthiness of the information they provide about research findings. It asked separately about issues of scientific integrity as a way to assess potential areas of mistrust toward medical researchers.

The survey finds a third of Black Americans say that medical research scientists do a good job conducting research all or most of the time, while another 46% say they do this some of the time. Just 18% say medical researchers do a good job only a little of the time or never.

Black Americans’ trust in medical researchers’ competence is on par with a 2019 Center survey.

The latest survey also finds Black Americans hold more positive than negative views of medical researchers when it comes to their care for the public interest and the trustworthiness of information they provide. Roughly a quarter of Black Americans (26%) say that medical researchers care about the public’s best interests all or most of the time; a 71% majority says they do so at least some of the time. The share who says medical researchers do this all or most of the time is down 7 points from 2019.

Similarly, 22% of Black Americans say that medical researchers provide fair and accurate information about their research all or most of the time and 73% say this occurs at least some of the time.

Black Americans express more concern around issues of scientific integrity, as does the U.S. public as a whole. For instance, only 12% of Black adults say medical researchers are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups all or most of the time, while another four-in-ten say this occurs some of the time. The share of Black adults who say medical researchers are transparent about potential conflicts of interest at least some of the time is down from 68% who said this in 2019.

Just one-in-ten Black adults say that medical research scientists admit and take responsibility for their mistakes all or most of the time; 47% say this occurs at least some of the time. This stands in contrast to 2019 when 66% of Black adults said medical researchers did this at least some of the time.

To the extent that medical research scientists are involved in research misconduct, most Black adults are skeptical that institutions would hold such researchers accountable for their misdeeds, as are most in the general U.S. public. In all, 43% of Black adults say medical research scientists face serious consequences at least some of the time if they engage in research misconduct, down from 59% in 2019.8

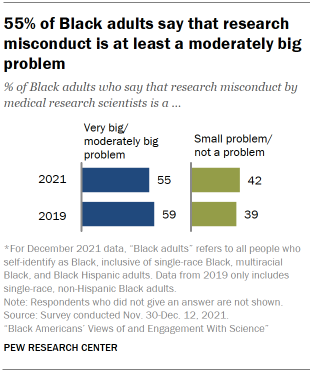

As shown below, a 55% majority of Black Americans consider research misconduct among this group to be a very big or moderately big problem. Those figures were roughly the same in 2019. Then, as now, Black Americans were more likely than U.S. adults overall to consider medical research misconduct to be at least a moderately big problem.

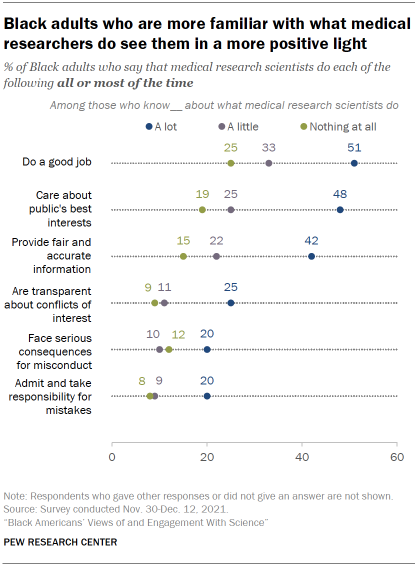

Greater familiarity with the work of medical researchers is associated with more positive views of them

The work of medical research scientists is not always front-of-mind for most people. The Center survey provided a brief description of what medical research scientists do, stating: “Medical research scientists conduct research to investigate human diseases, and test methods to prevent and treat them.”

In response, 12% of Black adults say they know a lot of about the work of medical research scientists, while a 58% majority says they know a little about it and another 28% say they know nothing at all about this.

The share of Black adults who are most familiar with medical researchers are markedly more trusting of them to do a good job, care about people’s best interests and provide fair and accurate information about their research findings. For example, 51% of this group says that medical research scientists do a good job conducting research all or most of the time.

Those who say they know a lot about medical research scientists also tend to express less skepticism of medical researchers on issues of scientific integrity compared with other Black adults, although these differences are relatively modest.

Trust in medical research scientists along these dimensions of competence, caring for the public, and trustworthiness of information also tends to be stronger among Black adults ages 65 and older, as well as among those who describe their political views as liberal. But concerns about issues of scientific integrity are shared to about the same degree across age groups and political ideology. See the Appendix for details.

75% of Black adults have heard about the Tuskegee study; a majority are skeptical that research procedures today will prevent serious misconduct

Discussions of Black Americans’ trust and mistrust in the medical research community often point to the legacy of past abuses, particularly the Tuskegee syphilis study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service at Tuskegee, in which syphilis treatment was withheld from Black men in the study, resulting in preventable deaths and a worsening of symptoms among study participants. The study began in 1932 and did not end until 1972, after the details of the study were publicized in the media.

Participants in all six focus groups with Black adults conducted by Pew Research Center in July 2021 referred to past research mistreatment in discussions of trust in the medical community, and most groups brought up the Tuskegee syphilis study. Some participants pointed to the lasting wariness in the Black community from this and other abuses when thinking about contemporary issues such as some Black Americans expressing initial hesitancy around getting a coronavirus vaccine.

“I have one word that informs my thought process on why there’s resistance in my community [to the coronavirus vaccines]. It’s Tuskegee.” – Black man, age 40-65

“As far as African Americans or Blacks, it’s more like we’ve been experimented on since we first were forcibly here on this land. So for us, it’s more like, ‘You know what? Let’s kind of wait and see what actually happens [with the coronavirus vaccines]. Let’s see the precautions.’” – Black woman, age 25-39

Other focus group participants mentioned a sense that such misdeeds had not been fully acknowledged, seeing that as a first step toward building more trust between medical researchers and Black Americans. And several participants pointed to an ongoing sense that medical doctors and researchers do not fully understand – or devote equal resources to – symptoms and illnesses that disproportionately affect Black people.

“Honesty, I think acknowledging that [the medical field] was built on these kinds of biases against people, and working on changing it to where you understand Black bodies … because how we treat blood, how blood pressure is treated and Black people are treated is different than White people.” – Black woman, age 25-39

“With Tuskegee, even now, any of the history of gynecology, you assume that Black people don’t feel as much pain, you don’t take their issues seriously. And going back to that Tuskegee, it was not that long ago. It was only 48 years or so ago. So it’s hard to erase that, and even now the bias that the medical community has, you can’t exactly fix that with, ‘Oh, okay. You need to get a vaccine or this, that, and the other.’ It really takes acknowledging the previous wrongdoings. Also, the [Henrietta] Lacks cells, all of that stuff makes it hard for people, African-Americans to actually trust it.” – Black woman, age 25-39

“But scientifically, I just don’t feel like there are enough doctors who have been looking out for our people historically, here, for me to trust their opinions.” – Black man, age 25-39

The Center survey also asked people about their familiarity with the Tuskegee syphilis study, as well as several other cases that involved racial and ethnic minority groups and raised ethical questions or were later found to violate ethical codes of conduct.

Three quarters of Black adults say they have heard or read a lot (49%) or a little (26%) about the Tuskegee study. About a quarter (24%) say they have heard nothing at all about this study.

The share of Black adults familiar with the Tuskegee study is far greater than among the U.S. adult population, generally.

About two-thirds of Black adults (68%) also say they have heard or read at least a little about medical doctors who sterilized women in racial and ethnic minority groups without their full understanding of what was being done.

About half of Black adults (48%) say they have heard or read at least a little about the case of Henrietta Lacks, an African American woman whose cancer cells were used by medical researchers, without her or her family’s knowledge or consent.

One controversial study is comparatively less familiar to survey respondents. About a third of Black adults (32%) say they have heard at least a little about medical testing done in Puerto Rico using high-dose birth control pills without a full explanation of the study and its risks.

Older Black adults are particularly likely to say they are familiar with the Tuskegee study. About two-thirds of Black adults ages 65 and older (65%) say they have heard or read a lot about this study.

Still, a majority of Black adults ages 18 to 29 say they have heard either a lot (35%) or a little (24%) about the study.

Black Americans with higher levels of education are also more likely to say they have heard something about the Tuskegee study. And 71% of those with a postgraduate degree say they have heard a lot about this.

About six-in-ten Black adults are skeptical that past research abuses are unlikely to occur again because of changes to research procedures

In response to the Tuskegee syphilis study and others, the federal government established a set of principles and regulations in 1979 to govern research conducted by the federal government and research by organizations that receive government funding.

Even so, 61% of Black adults say that research misconduct is just as likely to happen today as it has been in the past, while far fewer (35%) say that procedures in place today prevent serious cases of research misconduct.

The view that research misconduct is just as likely to occur today as in the past is widely shared across gender, age, education and political ideology.

Concerns about the potential for research misconduct is widely shared among all Americans; 60% of U.S. adults say that research misconduct is just as likely to happen today as in the past, while 38% say that procedures in place today prevent serious cases of research misconduct.

55% of Black adults consider medical research misconduct to be at least a moderately big problem today

Asked more generally about research misconduct, 55% of Black adults say that medical research misconduct is a very big (19%) or moderately big problem (36%). About four-in-ten (42%) consider it to be no more than a small problem.

Views on this are comparable to those in a previous 2019 Center survey. In both years, Black adults were more likely than the general U.S. public to consider research misconduct at least a moderately big problem. (In the new survey, 48% of U.S. adults say research misconduct by medical research scientists is at least a moderately big problem, the same share as in 2019.)

Younger Black Americans are a bit more likely to consider research misconduct a problem: 58% of those under age 50 say this is at least a moderately big problem compared with 51% among those ages 50 and older.

Black adults with lower levels of education express more concern about this issue than those with a college degree or higher education. Roughly six-in-ten Black adults with some college or less education (57%) say research misconduct is at least a moderately big problem today; 49% of those with a college or postgraduate education say this. See more details in the Appendix.