73% say they are vaccinated, but at least half express confusion, concern over vaccine information and health impacts

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans are continuing to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 10,348 U.S. adults from Aug. 23 to 29, 2021.

Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

See here to read more about the questions used for this report, along with responses and its methodology.

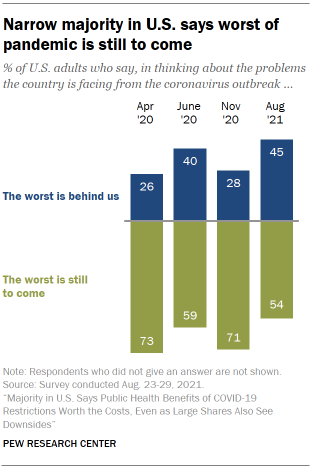

More than a year and a half into the coronavirus outbreak, large shares of Americans continue to see the coronavirus as a major threat to public health and the U.S. economy. And despite widespread vaccination efforts, 54% of U.S. adults say the worst of the outbreak is still to come.

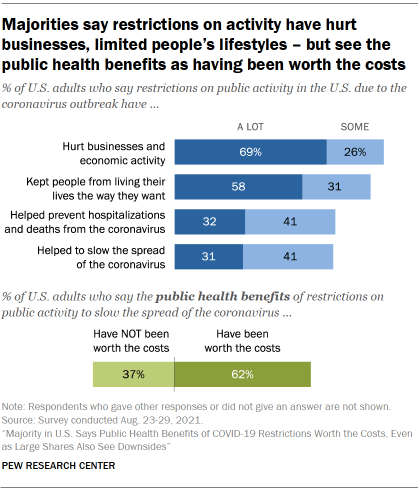

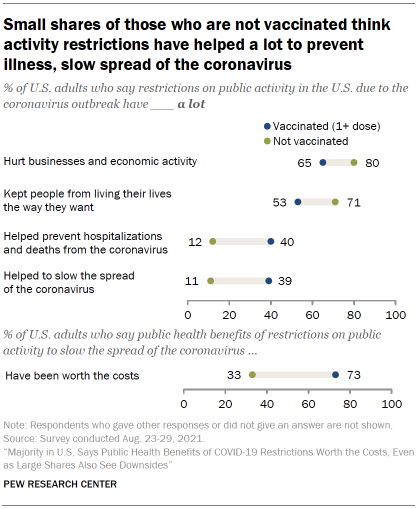

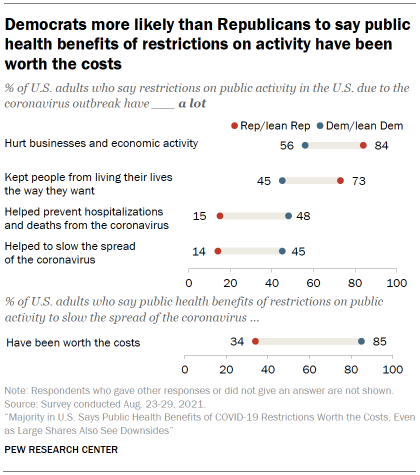

The toll of restrictions on public activities in order to slow the spread of the coronavirus is deeply felt across groups: Overwhelming majorities say restrictions have done a lot or some to hurt businesses and economic activity and keep people from living their lives the way they want. Smaller majorities say these restrictions have helped at least some to prevent hospitalizations and deaths from the coronavirus and to slow the spread of the virus. Still, when asked to issue an overall judgment, Americans on balance view the public health benefits of these restrictions as having been worth the costs (62% to 37%).

A new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted from Aug. 23 to 29 among 10,348 U.S. adults, prior to President Joe Biden’s announcement of COVID-19 vaccine mandates for employers, finds that 73% of those ages 18 and older say they’ve received at least one dose of a vaccine for COVID-19, with the vast majority of this group saying they have received all the shots they need to be fully vaccinated. About a quarter of adults (26%) say they have not received a vaccine.

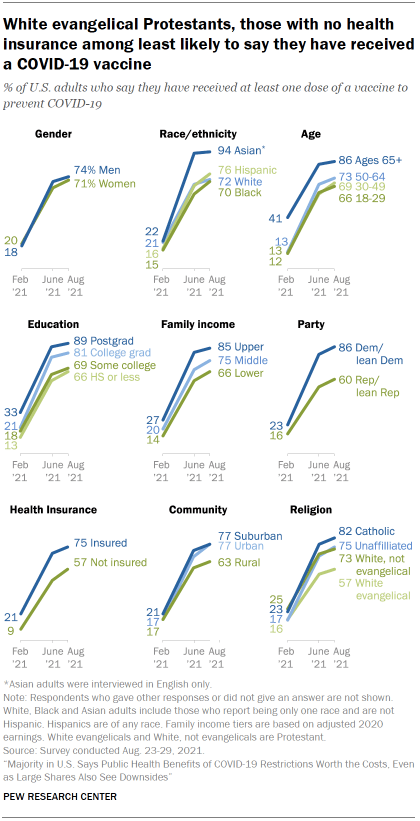

Vaccination rates vary significantly across demographic groups, with smaller majorities of younger adults, those with lower family incomes and those living in rural areas saying they’ve received a COVID-19 vaccine. No more than six-in-ten of those without health insurance and White evangelical Protestants say they’ve been vaccinated (57% each). Notably, Black adults are now about as likely as White adults to say they’ve received a vaccine. Earlier in the outbreak, Black adults were less likely than White adults to say they planned to get a COVID-19 vaccine.

Partisan affiliation remains one of the widest differences in vaccination status: 86% of Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 60% of Republicans and Republican leaners.

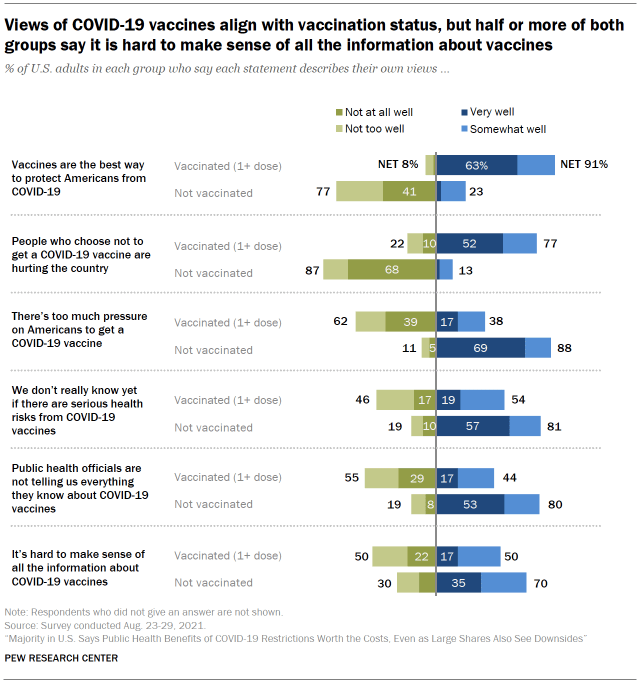

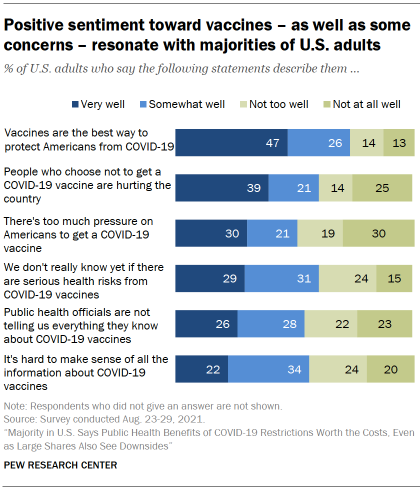

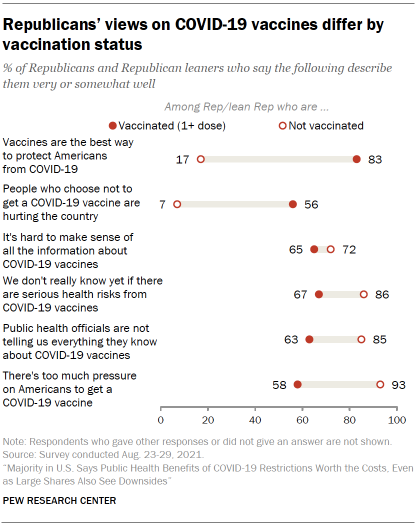

Americans express a range of sometimes cross-pressured sentiments toward vaccines. Overall, 73% say the statement “vaccines are the best way to protect Americans from COVID-19” describes their views very or somewhat well; 60% say their views are described at least somewhat well by the statement “people who choose not to get a COVID-19 vaccine are hurting the country.”

At the same time, 51% of the public says that the phrase “there’s too much pressure on Americans to get a COVID-19 vaccine” describes their own views very or somewhat well. And 61% say the same about the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines.”

Vaccinated adults and those who have not received a vaccine differ widely in their views of vaccines – as well as other elements of the broader coronavirus outbreak. For instance, 77% of vaccinated adults say the statement “people who choose not to get a COVID-19 vaccine are hurting the country” describes them at least somewhat well. By contrast, 88% of those who have not received a vaccine say that “there’s too much pressure on Americans to get a COVID-19 vaccine” describes their own views very or somewhat well.

However, vaccinated adults are not without anxieties and concerns surrounding vaccines: 54% of this group says the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes them very or somewhat well, and 50% say the same about the statement “it’s hard to make sense of all the information about COVID-19 vaccines.”

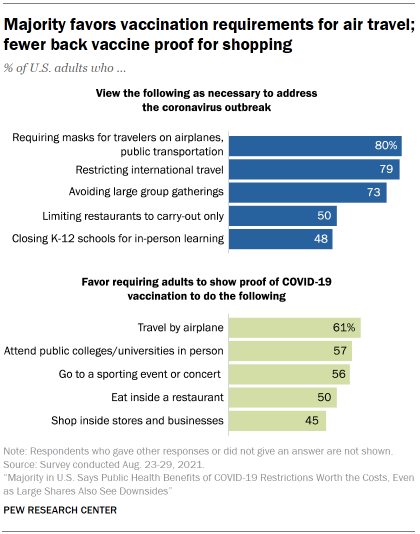

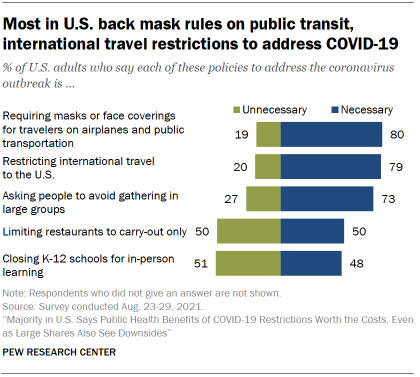

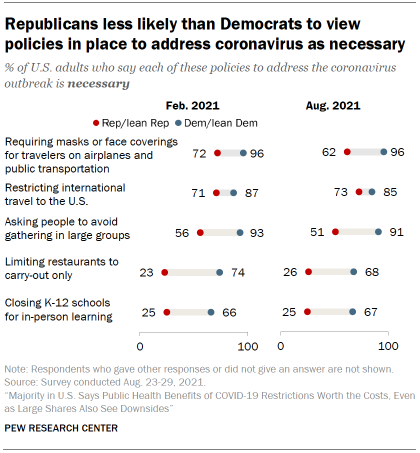

With the delta variant having changed the trajectory of the outbreak in the United States and around the world, large majorities continue to see a number of steps as necessary to address the coronavirus, including requiring masks for travelers on airplanes and public transportation (80%), restricting international travel (79%) and asking people to avoid gathering in large groups (73%).

The public is closely divided over limiting restaurants to carry-out and closing K-12 schools for in-person learning: About as many adults say these steps are unnecessary as say they are necessary.

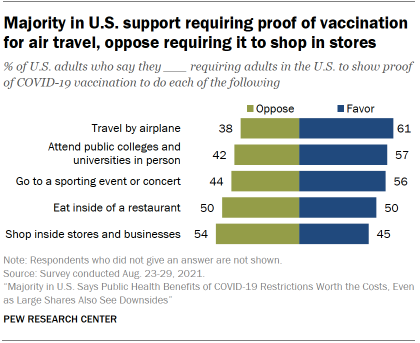

Vaccination requirements for in-person activities have gone into effect in a number of U.S. cities, including New Orleans, New York City and San Francisco. A 61% majority of Americans favor requiring adults to show proof of vaccination before being allowed to travel by airplane. More than half also say proof of vaccination should be required to attend public colleges and universities (57%) and to go to sporting events and concerts (56%).

However, the public is less convinced that vaccine requirements are needed in other settings. Equal shares of Americans favor and oppose requiring proof of vaccination to eat inside of a restaurant (50% vs. 50%), and 54% say they oppose a vaccination requirement to shop inside stores and businesses.

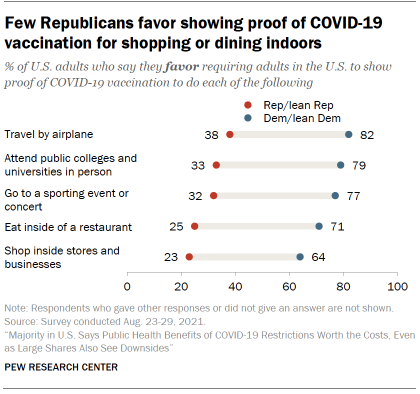

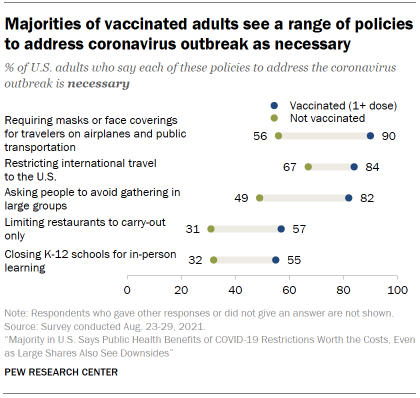

The intertwined dynamics of partisan affiliation and vaccination status are visible in views of policies to limit the spread of the coronavirus and vaccine requirements. Democrats offer broad support for most measures, while Republicans back select steps – like limiting international travel and requiring masks on public transportation – while opposing others and offering very little support for vaccine mandates. Similarly, vaccinated adults are far more supportive of policy steps aimed at limiting the spread of the coronavirus – and vaccine requirements – than are those who have not received a COVID-19 vaccine.

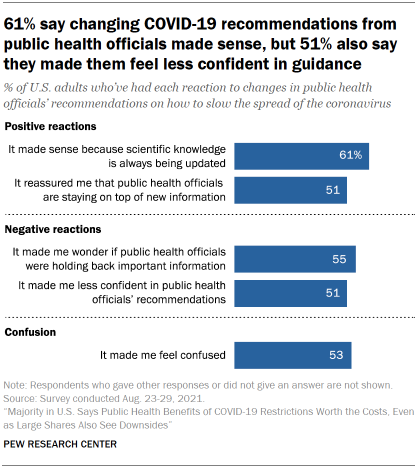

Changes to public health guidance over course of outbreak: understandable, but also a source of concern for at least half of Americans

Over the course of the pandemic, public health officials have changed their recommendations about how to slow the spread of the coronavirus in the U.S.

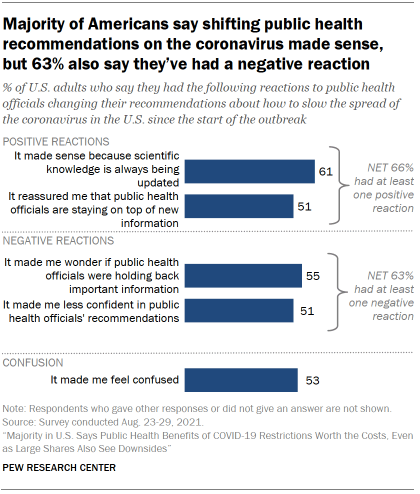

A majority of Americans (61%) say changes to public health recommendations since the start of the outbreak have made sense because scientific knowledge is always being updated. About half (51%) say these changes have reassured them that public health officials are staying on top of new information.

However, changes to public health guidance have also sparked confusion and skepticism among significant shares of the public: 55% say changes made them wonder if public health officials were holding back important information, 53% say it made them feel confused and 51% say it made them less confident in officials’ recommendations.

Taken together, 63% of U.S. adults say they’ve felt at least one of two negative reactions regarding public health officials because of changing guidance: wondering if they were holding back important information or feeling less confident in their recommendations.

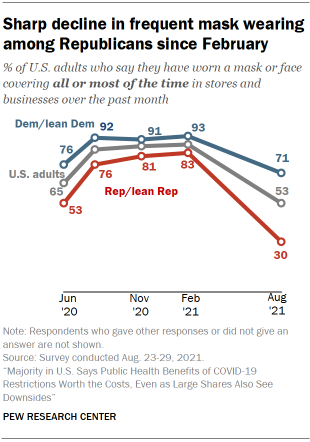

Mask wearing – among the most visible examples of shifting public health guidance, as well as a policy flashpoint at the state and local level – has become less frequent since earlier this year. Overall, 53% of U.S. adults say they’ve been wearing a mask or face covering all or most of the time when in stores and businesses over the last month, down 35 percentage points from 88% who said this in February (when mask requirements around the country were more widespread).

The practice of mask wearing is now far more common among Democrats and those who have been vaccinated against COVID-19. Democrats are now more than twice as likely as Republicans to say they’ve been wearing a mask in stores and businesses all or most of the time in recent weeks (71% vs. 30%). In February, large shares of both Democrats and Republicans had reported frequent mask wearing (93% and 83%, respectively).

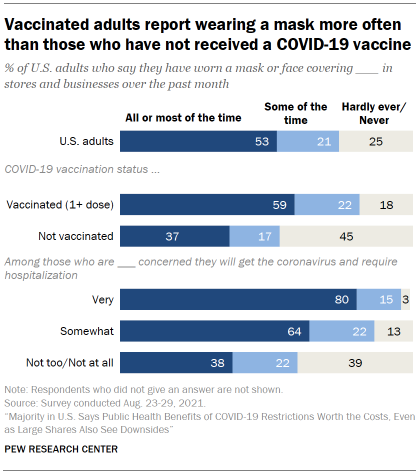

People who have received a COVID-19 vaccine (59%) are more likely than those who have not (37%) to say they’ve been wearing a mask all or most of the time when inside stores or businesses. Frequent mask wearing is especially high among those who say they are very concerned about getting a serious case of the disease (80%).

Black adults about as likely as White adults to have received a COVID-19 vaccine

Vaccination rates differ across key demographic groups and traits, including age, family income, partisanship, health insurance status, community type and religious affiliation.

Comparable majorities of Black (70%) and White (72%) adults have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Among Hispanic adults, 76% say they have received a vaccine, as do an overwhelming majority of English-speaking Asian adults (94%).

At earlier stages of the outbreak, Black adults had expressed significantly lower levels of intent to get a COVID-19 vaccine than White adults.

The vaccination rate among White evangelical Protestants continues to lag behind those of other major religious groups: 57% of White evangelicals say they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 73% of White Protestants who are not evangelicals, 75% of religiously unaffiliated adults and 82% of Catholics. For more details on vaccination status by religion, see the Appendix.

Older adults remain more likely than younger adults to have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. Age differences in vaccination status are much more pronounced among Republicans and Republican leaners than among Democrats and Democratic leaners. See the Appendix for more details.

These are among the principal findings from Pew Research Center’s survey of 10,348 U.S. adults conducted from Aug. 23 to 29, 2021, on the coronavirus outbreak and Americans’ views of a COVID-19 vaccine. The survey also finds:

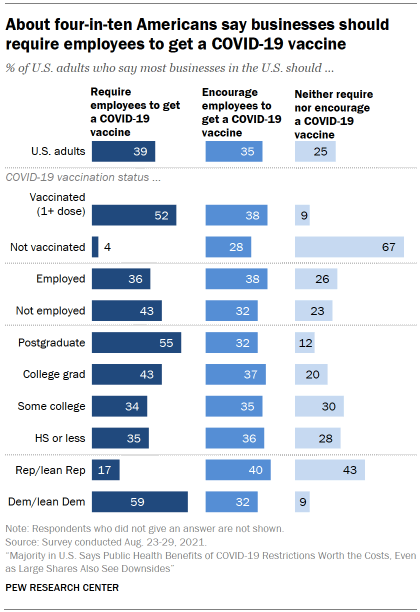

39% say most businesses in the U.S. should require employees to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Another 35% say businesses should encourage employees to get a vaccine, but not require it. A quarter of the public says most businesses should neither require nor encourage employees to get a COVID-19 vaccine. The survey was fielded before President Joe Biden’s announcement that employers with more than 100 workers will be required to have their workers vaccinated or tested weekly for the coronavirus.

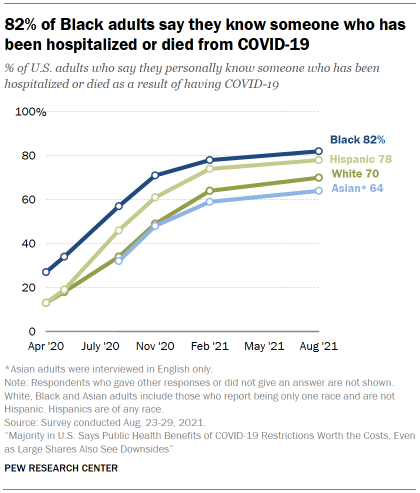

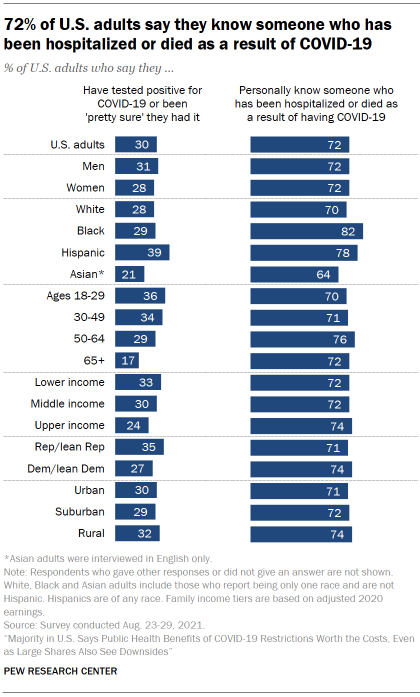

72% say they personally know someone who has been hospitalized or died from COVID-19. As has been the case throughout the outbreak, larger shares of Black (82%) and Hispanic (78%) adults than White (70%) and English-speaking Asian adults (64%) say they personally know someone who has been hospitalized or died as a result of the coronavirus.

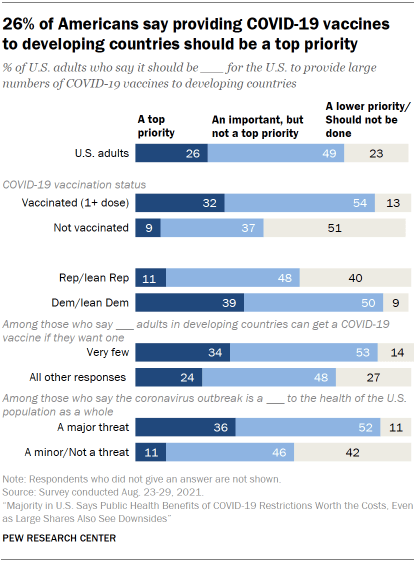

A relatively small share of Americans (26%) are aware that few adults in developing countries have access to COVID-19 vaccines. A majority (76%) places importance on the U.S. providing large numbers of COVID-19 vaccines to developing countries, though just 26% call this a top priority for the U.S.

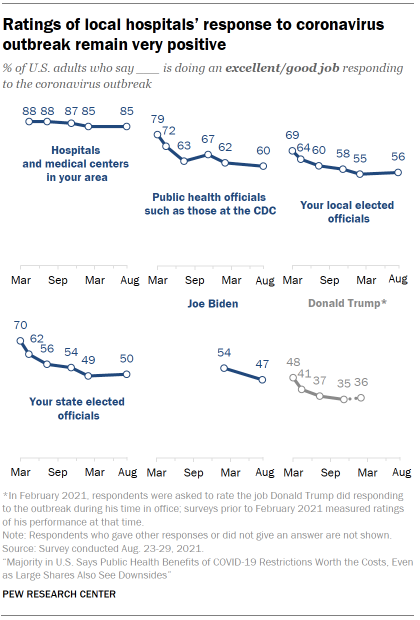

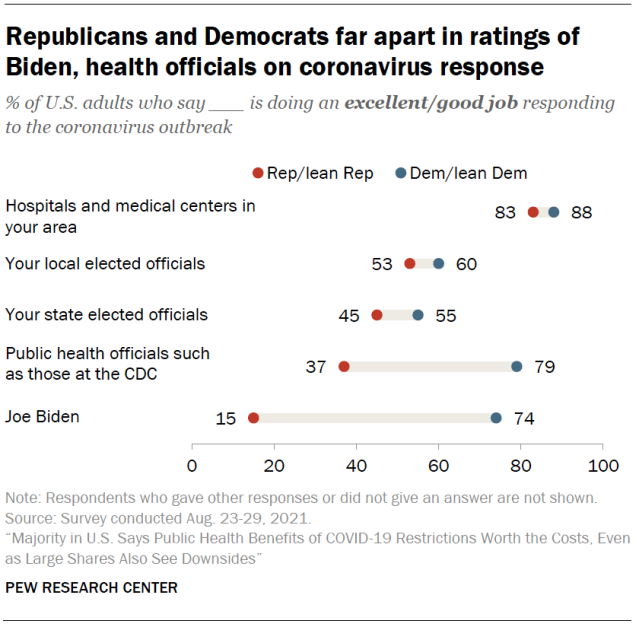

Biden’s job ratings for handling the outbreak have declined. Larger shares now say Joe Biden is doing an only fair or poor job (52%) responding to the coronavirus outbreak than say he is doing an excellent or good job (47%). In February, 54% said he was doing an excellent or good job. By contrast, Americans continue to give very high marks to hospitals and medical centers in their area: 85% say they are doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak.

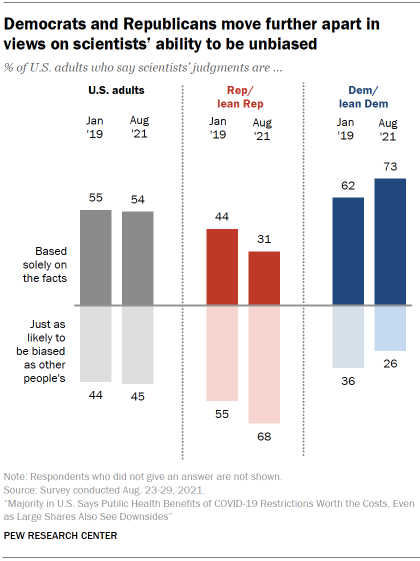

Republicans grow more skeptical of scientists’ judgment. Nearly seven-in-ten Republicans (68%) say scientists’ judgments are just as likely to be biased as other people’s, up from 55% who said this in January 2019. By contrast, a growing share of Democrats take the opposite view and say scientists make judgments solely on the facts (73% of Democrats say this today, up from 62% in 2019).

Large partisan gap persists in whether COVID-19 poses serious public health threat

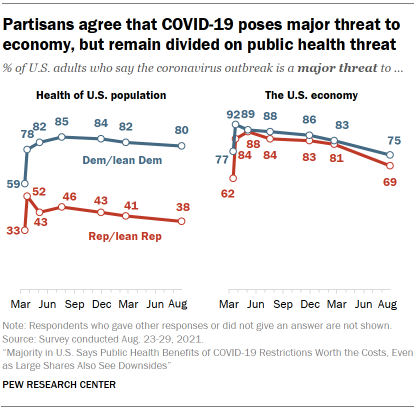

A majority of Americans (61%) continue to say the coronavirus outbreak poses a major threat to the health of the U.S. population as a whole. Another 33% say the virus is a minor threat, while just 6% say it is not a threat.

The share that views the coronavirus as a major threat to public health has largely held steady since late March of 2020, following the declaration of a national public health emergency in the U.S. The current share that views the coronavirus as a major threat to public health is about the same as it was in February 2021 (63%), when the country was coming out of a peak of cases and COVID-19-related deaths, and before widespread rollout of the vaccine.

A larger majority of U.S. adults (72%) say the coronavirus outbreak is a major threat to the U.S. economy. This is down slightly from February of this year, when 81% saw the outbreak as a major threat to the economy.

Large partisan divides persist in views of the public health threat posed by COVID-19. Eight-in-ten Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party say the outbreak is a major threat to the health of the U.S. population, while just 38% of Republicans and Republican leaners say the same. The partisan gap on this question is as wide as it has been at any point during the pandemic.

By contrast, majorities of both Democrats (75%) and Republicans (69%) see the COVID-19 outbreak as a major threat to the country’s economy. While economic concerns remain high, the shares of both parties who see the virus as a serious concern for the economy have moved lower since February, when 83% of Democrats and 81% of Republicans said it was a major threat.

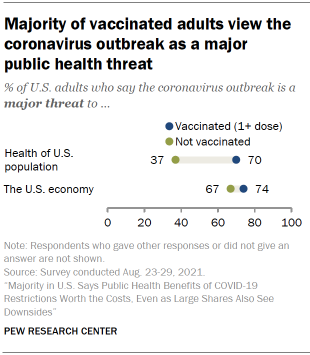

Vaccination status is closely tied to perceptions of the public health threat posed by the coronavirus outbreak: 70% of vaccinated adults view it as a major threat to the health of the U.S. population, compared with just 37% of adults who have not received a vaccine. There is shared concern over the impact on the economy, however: Majorities of both vaccinated (74%) and unvaccinated (67%) adults say the coronavirus poses a major threat to the U.S. economy.

Hospitals, medical centers continue to receive positive ratings for their outbreak response; Biden’s ratings decline

The public continues to rate the job their local hospitals have done responding to the coronavirus very positively; these ratings have been consistently high since the early days of the pandemic. Ratings for President Joe Biden’s handling of the outbreak have declined since February and now tilt more negative than positive. Assessments of other groups, including public health officials and state and local elected officials, are steady since February, but remain lower than they were in the early stages of the outbreak.

Overall, 47% say Biden is doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak, while slightly more (52%) say he is doing an only fair or poor job. Ratings for Biden have declined since February, shortly after he took office, when 54% said he was doing an excellent or good job.

A large majority of Americans (85%) say their hospitals and medical centers are doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak, identical to the share who said this in February 2021.

Six-in-ten say public health officials, such as those at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), are doing an excellent or good job in their coronavirus response. This rating is lower than it was during the early months of the outbreak, but about the same as it was in February of this year (62%).

A majority of Americans (56%) also say that their local elected officials are doing an excellent or good job responding to the outbreak. A slightly smaller share (50%) rate their state elected officials’ responses as excellent or good. As with ratings of public health officials, assessments of local and state elected officials are lower than they were early in the outbreak, but are about the same as they were when the questions were last asked six months ago.

Republicans and Democrats share positive assessments of the COVID-19 response from their local hospitals and medical centers but differ widely on the job public health officials and Biden are doing.

Large majorities of Republicans (83%) and Democrats (88%) say hospitals and medical centers in their area are doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak.

By contrast, a much larger share of Democrats (79%) than Republicans (37%) give positive ratings to the job public health officials, such as those at the CDC, have done responding to the outbreak. Ratings of public health officials among Republicans are down 7 percentage points since February; as a result, the partisan gap in assessments of public health officials has grown even wider (from 35 points to 42 points in the current survey).

Partisan divides are even larger for ratings of Biden. About three-quarters of Democrats (74%) say he is doing an excellent or good job responding to the coronavirus pandemic, compared with just 15% of Republicans – a 59-point gap. Ratings of Biden are down among both parties since February, when 84% of Democrats and 20% of Republicans rated his performance highly.

The size of the partisan gap in ratings of Biden is similar to differences seen in ratings of former President Donald Trump at the end of his administration. In February, 71% of Republicans said he did an excellent or good job responding to the pandemic during his time in office, compared with just 7% of Democrats.

There are modest differences between Republicans and Democrats in assessments of how their local and state elected officials are handling the outbreak. Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to rate the job being done by local officials (60% vs. 53%) and state elected officials (55% vs. 45%) as excellent or good.

54% of Americans say worst still to come from coronavirus outbreak

Thinking about the problems the country is facing from the outbreak, a narrow majority (54%) says they think the worst is still to come, while 45% say the worst is behind us.

Views are more positive than they were in November 2020 – before COVID-19 vaccines were approved for use in the U.S. – when just 28% of Americans thought the worst was behind us and 71% said the worst was still yet to come.

Republicans and Republican leaners are slightly more optimistic about the state of the outbreak than Democrats and Democratic leaners: 53% of Republicans say the worst is behind us, while 59% of Democrats take the opposing view and think the worst is still to come.

Adults who have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine and those who have not view the state of the coronavirus outbreak in similar terms: 53% of vaccinated and 56% of unvaccinated adults say the worst of the problems from the outbreak are still to come.

The toll of restrictions on public activity are widely felt, but majority in U.S. sees public health benefits as worth the cost

Nearly all adults in the U.S. say that coronavirus-related restrictions on public activity have hurt businesses and economic activity either a lot (69%) or some (26%); just 5% say these restrictions have hurt businesses not too much or not at all.

Large shares also say restrictions on public activity have kept people from living their lives the way they want either a lot (58%) or some (31%).

Americans are less convinced of how much the restrictions have helped to prevent hospitalizations and deaths from the coronavirus and helped to slow its spread. Majorities say the restrictions have helped at least some in each regard, but only about three-in-ten say they have done a lot to help prevent hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 (32%) or slow the spread of the coronavirus (31%).

Nonetheless, when asked to assess the overall impact of the restrictions on public activity, a majority of Americans (62%) say the public health benefits have been worth the costs; significantly fewer (37%) say they have not been worth the costs.

Vaccinated adults (those who have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine) are less likely than those who have not received a vaccine to say restrictions on public activity have done a lot to hurt businesses and keep people from living their lives, and they are more likely to say restrictions have done a lot to help prevent serious illnesses and slow the virus’s spread. For example, 40% of vaccinated adults say restrictions have helped a lot to prevent hospitalizations and deaths from the virus, compared with just 12% of unvaccinated adults who say the same.

These two groups arrive at differing conclusions about the overall impact of the restrictions: 73% of vaccinated adults say the public health benefits of the restrictions have been worth the costs, while 33% of those not vaccinated say this. A majority of those not vaccinated (65%) say the health benefits of the restrictions have not been worth the costs.

There are also wide differences in views of the public health restrictions by partisanship, with Republicans being more likely than Democrats to say the restrictions have had negative impacts, and less likely to say they have helped a lot to prevent severe illnesses and slow the spread of the coronavirus.

Majorities in U.S. back proof of vaccination for air travel, college students

As several cities and businesses around the country have begun requiring customers to show proof of COVID-19 vaccination to do things like eat at restaurants or attend concerts, Americans offer mixed views of these requirements, with opinion ranging from majority support to opposition, depending on the setting.

About six-in-ten Americans (61%) say they favor requiring adults in the U.S. to show proof of COVID-19 vaccination before being allowed to travel by airplane, while 38% would oppose such a requirement. While some U.S. airlines have required their employees to get vaccinated, they have so far stopped short of requiring proof of vaccination from travelers – although some destinations, such as Hawaii, require visitors to either show proof of vaccination or a negative coronavirus test result, or else quarantine for 10 days after arrival.

As the school year begins around the country, just under six-in-ten Americans (57%) say they favor requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination for students to attend public colleges and universities in person. More than 800 U.S. colleges are requiring vaccinations for students and staff to be on campus, and more are strongly encouraging vaccination.

A narrow majority of adults (56%) also support requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination in order to attend sporting events or concerts.

The public is evenly split over whether they would support or oppose being made to show proof of vaccination to eat inside of a restaurant. Some cities, such as New York, have required restaurants and bars to ask for proof of vaccination in response to rising infections and hospitalizations.

On balance, the public leans against requiring proof of vaccination to shop inside stores and businesses: 54% say they are opposed to this, while 45% support such a requirement.

Partisanship, as well as vaccination status, plays a large role in views about requiring coronavirus vaccines. Majorities of Democrats favor requiring adults to show proof of vaccination before doing all five of the activities included in the survey; by contrast, majorities of Republicans oppose each of these measures.

For example, 77% of Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party favor requiring those going to a sporting event or concert to show proof of vaccination, while 68% of Republicans and Republican leaners oppose requiring spectators to prove they’ve received a coronavirus vaccine.

Not surprisingly, adults who have not received a vaccine overwhelmingly oppose requiring proof of vaccination in these settings; roughly eight-in-ten or more oppose each of the five activities requiring proof of vaccination. Among those who have received at least one dose of a vaccine, majorities support requiring proof of vaccination, though the level of support varies from 56% for shopping inside stores and businesses to 77% for travel by airplane.

Differences in views by vaccination status exist within partisan groups. Among Republicans and Republican leaners, 55% of vaccinated Republicans favor requiring proof of vaccination for air travel, compared with 12% of unvaccinated Republicans. Just under half of vaccinated Republicans back proof of vaccination for attending events and public colleges and universities (compared with only about 10% of unvaccinated Republicans). However, when it comes to requirements to eat inside restaurants or shop, majorities of Republicans, regardless of vaccination status, oppose having to provide proof of vaccination. (60% of Republicans and Republican leaners are vaccinated; 38% are not.)

Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, differences are even wider, with majorities of vaccinated Democrats in favor of requiring proof of vaccination in all five settings and majorities of unvaccinated Democrats opposed to all five requirements. However, those who have not received a vaccine represent a small share of all Democrats (14%), compared with 38% among Republicans.

Requiring masks on transit, restricting international travel, avoiding large gatherings widely seen as necessary steps to address coronavirus

When asked about policies in place in some areas of the country to address the coronavirus outbreak, 80% of Americans say they think it is necessary to require masks for people traveling on airplanes or public transportation. A similar majority (79%) says it is necessary to restrict international travel to the U.S.

About three-quarters of U.S. adults (73%) also think asking people to avoid gathering in large groups is a necessary step to deal with the outbreak.

The public is closely divided on the necessity of two other policies: limiting restaurants to carry-out only (50% necessary, 50% unnecessary) and closing K-12 schools for in-person learning (48% necessary, 51% unnecessary). In-person learning has recently restarted at most schools around the country – although some schools have had to temporarily revert to remote instruction due to coronavirus outbreaks among students or staff.

The shares of Americans that support each of these measures have stayed relatively stable since the questions were last asked in February 2021.

Vaccinated adults (including those who have received one of two vaccine doses) are more likely to see each of these five policies as necessary to address the outbreak than adults who have not received a vaccine.

For instance, 82% of vaccinated Americans think it is necessary to ask people to avoid gathering in large groups. About half of unvaccinated adults (49%) say this policy is necessary, while 51% say it is unnecessary.

There also are wide differences in views of policies aimed at addressing the coronavirus outbreak by partisanship, with Democrats expressing significantly more support for each policy than Republicans.

However, the magnitude of the partisan gap varies by policy.

For instance, majorities of Democrats (85%) and Republicans (73%) say it’s necessary to restrict international travel to the U.S. in order to address the coronavirus outbreak (a 12-point partisan gap).

By contrast, Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say it is necessary to limit restaurants to carry-out only (68% vs 26%) and to close K-12 schools for in-person learning (67% vs. 25%).

Decline in share of U.S. adults who report frequent mask wearing

Public health guidance on mask wearing has changed over the course of the outbreak, and policies requiring masks – or preventing mask requirements – have varied widely at the state and local level.

In the current survey, 53% of adults say that in the past month they have worn a mask or face covering all or most of the time when in stores and businesses; 21% say they have worn one some of the time and 25% say they’ve worn a mask in these public places hardly ever or never.

The share of U.S. adults who say they’ve been wearing a mask all or most of the time is down 35 points since February, when mask mandates were more widely in place around the country than they are today. The decline in frequent mask wearing has been much greater among Republicans (down 53 points) than among Democrats (down 22 points). In February, there was a modest partisan divide on this question as large majorities of both Republicans (83%) and Democrats (93%) said they had been wearing a mask all or most of the time in public. Today, the partisan gap has grown dramatically to 41 points as Democrats are now far more likely than Republicans to report wearing a mask all or most of the time when in stores and businesses (71% vs. 30%).

Vaccinated adults are significantly more likely than those who have not received a COVID-19 vaccine to report frequently wearing a mask in public places.

About six-in-ten (59%) of those who have received at least one dose of a vaccine say they have been wearing a mask all or most of the time in stores and businesses over the last month. A much smaller share (37%) of those who have not received a COVID-19 vaccine report this level of mask wearing; 45% of this group say they have been wearing a mask in stores and businesses hardly ever or never in the last month.

There is a strong link between personal concern about getting a serious case of the coronavirus and mask wearing. Eight-in-ten of those who are very concerned about getting the coronavirus and requiring hospitalization say they’ve been wearing a mask all or most of the time in stores and businesses. The share who report frequent mask wearing falls to 64% among those who are somewhat concerned about getting a serious case of the coronavirus and to 38% among those who are not too or not at all about getting the coronavirus and requiring hospitalization.

Mask-wearing habits also differ significantly by the type of community where people live. Nearly seven-in-ten adults who live in urban areas (68%) say they’ve been wearing a mask all or most of the time in stores and businesses, compared with 51% of those in suburban areas and 42% of those in rural areas.

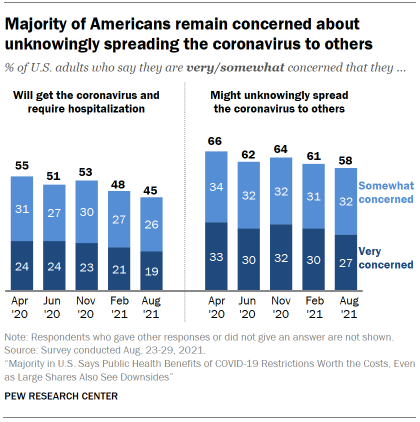

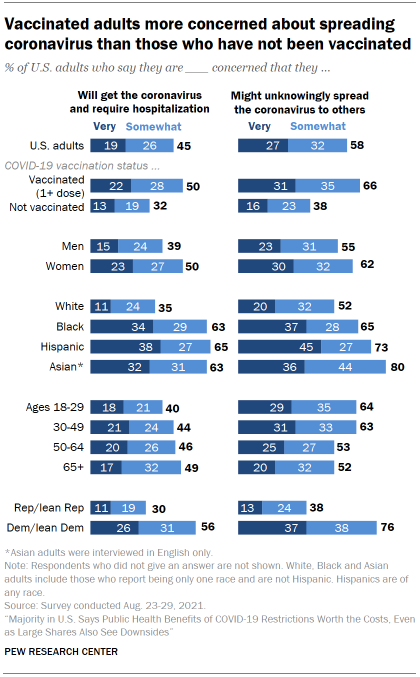

58% of Americans express concern about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus

A majority of Americans say they are either very (27%) or somewhat (32%) concerned that they might spread the coronavirus to other people without knowing that they have it. A smaller share (45%) say they are very (19%) or somewhat (26%) concerned that they will get the coronavirus and require hospitalization.

Concern over getting and unknowingly spreading the coronavirus has gradually edged lower since the start of the pandemic. In April 2020, 66% of U.S. adults were at least somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus (including 33% who were very concerned); at that time, 55% were at least somewhat concerned about getting a serious case themselves (24% very concerned).

There are wide differences in levels of concern over getting and spreading the coronavirus by vaccination status as well as by other characteristics such as party affiliation and race and ethnicity.

About two-thirds of vaccinated adults are very (31%) or somewhat (35%) concerned about unknowingly spreading COVID-19 to others. Half are at least somewhat concerned about getting a serious case themselves. By contrast, among those who have not received a vaccine, fewer than half express concern about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus (38%) or getting a serious case themselves (32%), including relatively small shares who say they are very concerned about this (16% and 13%, respectively).

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are far more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to say they are very or somewhat concerned about spreading the coronavirus to other people without knowing they have it (76% vs. 38%) and to say they are concerned about getting a serious case of the coronavirus themselves (56% vs. 30%).

White adults are much less likely than Black, Hispanic and English-speaking Asian adults to express concern over spreading the coronavirus or getting the coronavirus and requiring hospitalization. Eight-in-ten English-speaking Asian adults, 73% of Hispanic adults and 65% of Black adults say they are very or somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus to others, compared with 52% of White adults.

Among White adults, Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to express concern about getting or spreading COVID-19. For instance, nearly three-quarters of White Democrats (74%) say they are very or somewhat concerned about unknowingly spreading the coronavirus, compared with 35% of White Republicans. (Overall, larger shares of White adults than Black, Hispanic and English-speaking Asian adults identify with or lean toward the Republican Party.)

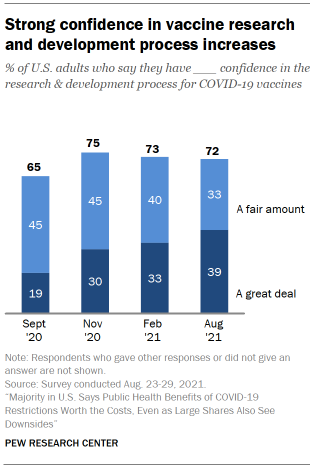

About seven-in-ten Americans have at least a fair amount of confidence in COVID-19 vaccine research and development process

Strong confidence in the vaccine research and development process has risen steadily over the past year. The share saying they have a great deal of confidence that the research and development process has produced safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines has increased 20 percentage points (to 39%) over the past year and is up 6 points since February.

A majority of Americans (72%) continue to say they have at least a fair amount of confidence that the research and development process has produced safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines.

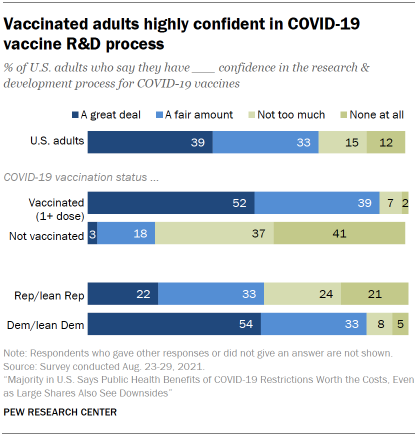

As with earlier Center surveys, levels of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine research and development process are strongly tied to vaccination status. Nearly all of those who have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (91%) say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in the vaccine R&D process, including 52% who say they have a great deal of confidence.

By contrast, only 21% of those who are not vaccinated say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in the vaccine R&D process (including just 3% who have a great deal of confidence).

A larger majority of Democrats than Republicans say they have at least a fair amount of confidence in the vaccine research and development process (86% vs. 55%). Among Democrats, 54% express a great deal of confidence (just 22% of Republicans say the same).

Americans who are vaccinated and not vaccinated see COVID-19 vaccines in starkly different lights

The development of COVID-19 vaccines and their uptake among the U.S. public are the center of the public health strategy to combat the coronavirus outbreak.

When asked how well various statements about coronavirus vaccines describe them, the public expresses a mix of positive and negative sentiments. Overall, 73% of adults say that the statement “vaccines are the best way to protect Americans from COVID-19” describes their own views very or somewhat well; 27% say it describes their views not too or not at all well. A majority (60%) also say the statement “people who choose not to get a COVID-19 vaccine are hurting the country” describes their views at least somewhat well.

At the same time, sizable shares of the public express concerns regarding COVID-19 vaccines. About six-in-ten (61%) say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well.

When it comes to information about vaccines, 54% align with the statement “public health officials are not telling us everything they know about COVID-19 vaccines,” and 55% say that “it’s hard to make sense of all the information about COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views well.

The public is about evenly split over the statement “there is too much pressure on Americans to get a COVID-19 vaccine”: 51% say this describes their views very or somewhat well, while 48% say it describes how they feel not too or not at all well.

Vaccinated adults are much more likely than those who are not vaccinated to say the sentiment that vaccines are the best way to protect Americans from COVID-19 describes them at least somewhat well (91% vs. 23%). There is a similarly large gap when it comes to expressing alignment with that view that people who choose not to get vaccinated are hurting the country (77% vs. 13%).

However, even among those who are vaccinated, some concerns about COVID-19 vaccines resonate: 54% of vaccinated adults say the statement “we don’t really know yet if there are serious health risks from COVID-19 vaccines” describes their views very or somewhat well. Taken together, 70% of vaccinated adults express alignment with at least one of four sentiments of confusion or concern about COVID-19 vaccines.

Those who have not received a COVID-19 vaccine are less likely to express cross-cutting attitudes about vaccines. Fewer than 25% say they are described at least somewhat well by the statements that vaccines are the best way to protect Americans from COVID-19 and that people who choose not to get a COVID-19 vaccine are hurting the country.

Vaccination status also matters within partisan coalitions when assessing views toward vaccines. Among Republicans who have received a vaccine, 83% say the statement “vaccines are the best way to protect Americans from COVID-19” describes their views very or somewhat well, and 56% say this about the statement “people who choose not to get a COVID-19 vaccine are hurting the country.” Republicans who have not received a vaccine express very low levels of alignment with these two statements. (Six-in-ten Republicans and Republican leaners have received at least one dose of a vaccine, while 38% have not.)

More than half of Republicans, regardless of vaccination status, say each of the four statements of confusion or concern regarding vaccines describes their views well, though larger majorities of unvaccinated than vaccinated Republicans express alignment with these statements.

There also are differences in these views by vaccination status among Democrats, with vaccinated Democrats more likely than unvaccinated Democrats to say they’re described well by positive sentiments toward vaccines; the opposite pattern is seen for sentiments expressing confusion or concern. However, unvaccinated adults make up a relatively small share of all Democrats and Democratic leaners: Just 14% of Democrats say they have not received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Fewer than half think businesses should require vaccines for employees, but a majority think they should at least encourage it

Asked to think about workplaces and COVID-19 vaccines, 39% of the public says most businesses should require their employees to get a vaccine, while another 35% say businesses should encourage employees to get a COVID-19 vaccine, but not require it. A quarter of the public says employers should neither require nor encourage employees to get vaccinated.

Views on this question differ only modestly by employment status. And among adults under 50, the same share of those employed and not employed say most businesses should require workers to get a vaccine (34%).

A majority of Democrats (59%) say most businesses should require employees to get a COVID-19 vaccine, compared with 17% of Republicans.

Those with higher levels of education are more likely to favor a vaccination requirement. Adults with a postgraduate education are 20 points more likely than those with high school or less education to support requirements (55% vs. 35%).

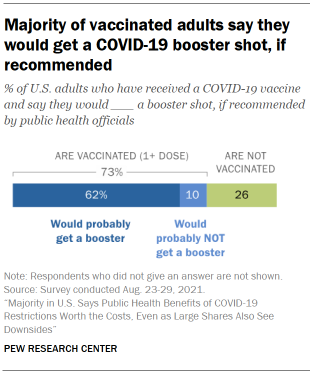

Most vaccinated adults are open to getting a COVID-19 booster shot

The share of the adult public that says they’ve received at least one dose of a vaccine for COVID-19 rose dramatically between February and June of this year (from 19% to 67%), as vaccines became more widely available. Since June, the share of adults who say they’ve received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine has increased 6 points to 73%.

In recent weeks the Food and Drug Administration has approved booster shots – an additional dose of a COVID-19 vaccine – for people with weakened immune systems, and the FDA and CDC continue to evaluate the potential need for booster shots among the general public.

Adults who have already received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine express broad openness to receiving a booster shot. A large majority of vaccinated adults (62% of the total public) say they would probably get a vaccine booster, if public health officials recommend an additional dose. A far smaller share of vaccinated adults (10% of the total public) say they would probably not get a vaccine booster.

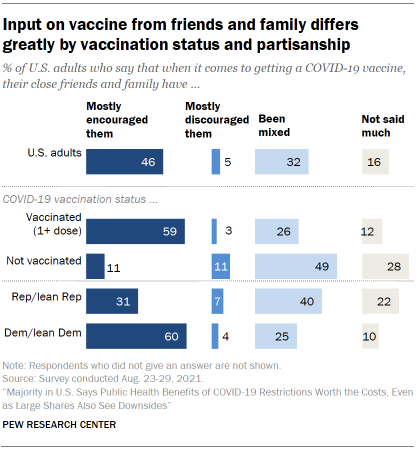

Divides over vaccines play out among family and friends

Adults who have received a COVID-19 vaccine and those who have not report distinctly different input from their friends and family when it comes to the vaccination decision.

A majority of vaccinated adults (59%) say their close friends and family have mostly encouraged them to get a coronavirus vaccine. Just 3% of vaccinated adults say their close friends and family have mostly discouraged them from doing this; 26% say the input has been mixed and 12% say they haven’t heard much from friends and family about vaccines.

By contrast, among those who have not received a COVID-19 vaccine, just 11% say their close friends and family have mostly encouraged them to get a coronavirus vaccine; another 11% say they have been mostly discouraged by friends and family from getting a vaccine. Among those who have not been vaccinated, about half (49%) describe the input from their close friends and family as mixed, with some encouraging them to get a vaccine and some discouraging them from doing so; 28% say their close friends and family haven’t said much about vaccines.

There are also wide differences on this question by partisanship. Six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic leaners say their close friends and family have mostly encouraged them to get a vaccine, while 25% say they’ve received mixed input and just 4% say they’ve mostly been discouraged from getting a vaccine.

Republicans and Republican leaners are much less likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say their close friends and family have mostly encouraged them to get a coronavirus vaccine (31% vs. 60%). Among Republicans, 40% say the input they received from close friends and family has been mixed, while 22% say their friends and family haven’t said much. Relatively few (7%) say they’ve mostly been discouraged from getting a vaccine.

Americans hold mixed reactions to changing public health guidance during the coronavirus outbreak

Over the course of the outbreak, public health guidance on how to deal with the coronavirus has changed, including information on core concepts such as how the coronavirus spreads and how effective masks are at limiting the spread of the virus.

Americans express a mix of both positive and negative reactions when asked how this changing guidance has made them feel.

A majority (61%) says changes to public health recommendations since the start of the outbreak made sense because scientific knowledge is always being updated. About half (51%) say the changing guidance reassured them that public health officials are staying on top of new information.

At the same time, the public also expresses negative reactions: 55% say the changing guidance made them wonder if public health officials were holding back important information, and 51% say these changes made them feel less confident in public health officials’ recommendations. Taken together, 63% of U.S. adults express at least one of two negative reactions to changing public health guidance.

Confusion was also a reaction experienced by just over half of adults: 53% say changing recommendations over the course of the outbreak made them feel confused.

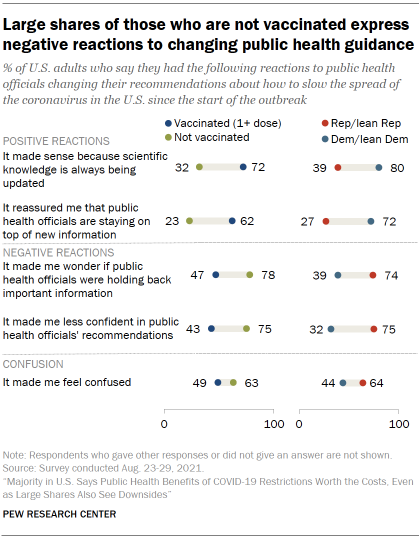

There are wide differences in reactions to changing guidance from public health officials by vaccination status and partisan affiliation.

U.S. adults who have not been vaccinated against COVID-19 are far more likely to express negative reactions to changes in guidance from public health officials than vaccinated adults. Large majorities of those who are not vaccinated say changing recommendations made them wonder if public health officials were holding back important information (78%) and say it made them feel less confident in public health officials’ recommendations (75%). Fewer than half of vaccinated adults express either of these two sentiments (47% and 43%, respectively).

Those who have been vaccinated are far more likely than those who have not to say changes to recommendations made sense because scientific knowledge is always being updated (72% vs. 32%).

There are comparably large differences by partisan affiliation in reactions to changes in public health recommendations, with Democrats more likely to express positive feelings and Republicans more likely to express negative reactions. For instance, Democrats are 41 points more likely than Republicans to say changes in recommendations made sense because scientific knowledge is always being updated (80% vs. 39%). When it comes to negative reactions, Republicans are 35 points more likely than Democrats to say that changing guidance made them wonder if public health officials were holding back important information (74% vs. 39%). But Democrats do not express exclusively positive responses to shifts in public health recommendations: 47% say they’ve experienced at least one of the two negative reactions to changing guidance, and 44% say they’ve felt confused.

Higher educational attainment is also connected with more positive reactions to changing health guidance. For example, about three-quarters of Americans with a postgraduate degree (76%) say changing guidance made sense because scientific understanding is always being updated. This compares with 66% of college graduates, 59% of those with some college experience and 54% of those with a high school diploma or less education. Educational differences occur on this question among both Republicans and Democrats.

Those with lower levels of education are especially likely to express negative reactions to changing guidance: For instance, 60% of those with a high school diploma or less and 58% of those with some college say changing recommendations about how to slow the spread of the coronavirus made them wonder if health officials were holding back important information; this view is less widely held among college graduates (50%) and postgraduates (41%).

However, there is little difference across levels of education in having felt confused by changing guidance from public health officials, with between 49% and 55% of all groups expressing this view. See the Appendix for details.

Majority of Americans know someone who has been hospitalized or died from COVID-19

More than 600,000 Americans have died as a result of COVID-19, and millions have been hospitalized from the disease. In the current survey, 72% of U.S. adults say they personally know someone who has been hospitalized or died as a result of having COVID-19.

As has been the case throughout the outbreak, Black (82%) and Hispanic (78%) adults are especially likely to say they know someone who has been hospitalized or died as a result of the coronavirus. Majorities of White (70%) and English-speaking Asian adults (64%) also say they know someone who has been hospitalized or died.

Across other major demographic groups, there are modest or no differences in the shares who say they know someone who has been hospitalized or died as a result of COVID-19. Democrats and Republicans are about equally likely to say this (74% and 71%, respectively); there is a modest difference in this experience between adults who have received a COVID-19 vaccine and those who have not (74% vs. 68%).

A year and a half into the coronavirus outbreak in the U.S., three-in-ten U.S. adults say they have tested positive for COVID-19 or been “pretty sure” they had it.

There are differences by age, race and ethnicity, income and partisan affiliation when it comes to having had COVID-19. Younger Americans are more likely than their older counterparts to say they have had the coronavirus. Those ages 18 to 29 are about twice as likely as those 65 and older to report they tested positive or were “pretty sure” they had COVID-19 (36% vs. 17%).

Hispanic adults (39%) are more likely than Black (29%), White (28%) or Asian (21%) adults to say they have had COVID-19.

One-third of adults with lower incomes say they have tested positive for COVID-19 or been pretty sure they had it, compared with 24% of upper-income adults.

Republicans are modestly more likely than Democrats to say they have had COVID-19 (35% vs 27%).

Few Americans know access to vaccines is limited in developing countries

Many developing countries continue to have a low supply of COVID-19 vaccines, with small shares of their populations currently vaccinated. In African countries, for instance, it is estimated that just about 3% of the adult population has received a COVID-19 vaccination.

Asked about the status of COVID-19 vaccines in developing countries, about a quarter of Americans (26%) correctly say that very few adults in developing countries can currently get a vaccine, if they want one. Roughly four-in-ten Americans (42%) say that about half or most adults in developing countries have access to COVID-19 vaccines, while 32% say they aren’t sure.

When asked about the U.S. role in the global distribution of vaccines, about three-quarters of Americans (76%) say providing COVID-19 vaccines to developing countries should be at least an important priority, though only 26% of U.S. adults say it’s a “top” priority. About a quarter (23%) say this should be a lower priority or should not be done at all.

Those who are vaccinated are more likely to favor providing large numbers of vaccines to developing countries, a pattern that holds among both Republicans and Democrats. Overall, Democrats place a higher priority on providing vaccines to developing countries than Republicans.

Americans who are aware that most people in developing countries do not have access to COVID-19 vaccines, and those who see COVID-19 as a major threat to public health in the U.S., are relatively more likely to prioritize providing COVID-19 vaccines to developing countries.

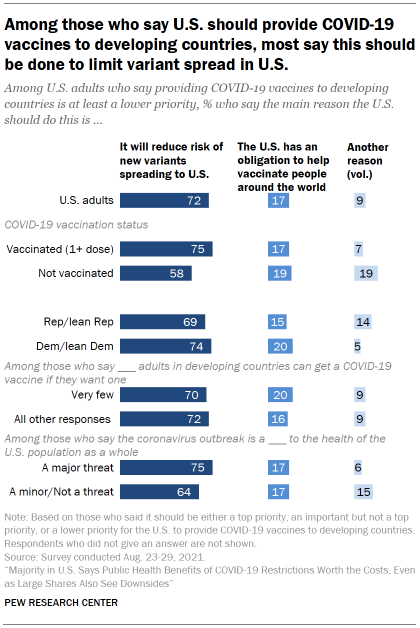

Infectious disease researchers have argued that countries with low vaccination rates are more likely to develop new coronavirus variants. Reducing the risk of new coronavirus variants spreading to the country is seen as the main reason why the U.S. should provide vaccines to developing countries (among those who give this at least some level of priority).

Among the 90% of adults who say providing vaccines to developing countries is a top, important or lower priority, 72% say the main reason to do this is to reduce the risk of new variants spreading to the U.S. About two-in-ten (17%) say the main reason to do this is because the U.S. has an obligation to help people around the world get vaccinated.

About one-in-ten (9%) volunteer another rationale for why the U.S. should provide vaccines to developing countries. Common volunteered responses include that both reducing the risk of variants and a U.S. obligation to help are equally important reasons, that providing vaccines is the humanitarian choice, and that the U.S. should provide vaccines due to the country’s excess supply.

Republicans grow more skeptical that scientists base judgments solely on the facts

Americans are closely divided over whether scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts or are just as likely to be biased as other people’s. In the current survey, 54% say scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts, compared with 45% who think scientists’ judgments are just as likely to be biased as those of other people. These overall views are about the same as they were in 2019, the last time this question was asked.

However, Democrats have become more likely – and Republicans less likely – to say scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts over the past two years. About three-in-ten Republicans and Republican leaners (31%) now say scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts, down 13 percentage points since 2019. About seven-in-ten (68%) Republicans think scientists’ judgments are just as likely to be biased as those of other people.

Among Democrats and Democratic leaners, 73% say scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts, up 11 points since 2019. The partisan gap in the share saying scientists’ judgments are based solely on the facts is now 42 points, much larger than the 18-point gap seen in 2019.

Recent Center surveys have also found growing political divides in confidence in scientists and views of the effect of science on society.

About seven-in-ten Americans see the scientific method as an iterative process

The survey also looked at Americans’ understanding of the scientific process. About seven-in-ten U.S. adults (71%) say the scientific method is an iterative process, with findings that are meant to be continually tested and updated, while 9% say the scientific method produces unchanging core principles and truths; 20% say they aren’t sure.

The share of Americans who see the scientific method as iterative is up slightly from November 2020 when 66% said this.

Americans with higher levels of education are more likely to say the scientific method produces findings meant to be continually tested and updated. About nine-in-ten (88%) of those with a postgraduate degree say this, compared with just 56% of those with a high school diploma or less. There are large educational differences on this question among both Democrats and Republicans.

CORRECTION (Sept. 15, 2021): A previous version of the chart “White evangelical Protestants, those with no health insurance among least likely to say they have received a COVID-19 vaccine” and a sentence in the report’s text misstated the share of White non-evangelical Protestants who have received at least one dose of a vaccine to prevent COVID-19. It should be 73% and has been updated to reflect that.