The Center’s survey takes a multifaceted approach to understanding public trust in scientists.1 Respondents were asked whether scientists in each of six specialties can be counted on to act with competence, to present their recommendations or research findings accurately, and to care about the public’s best interests – or, in some cases, patients’. In addition, respondents were asked about potential sources of mistrust, including issues of transparency and accountability for mistakes or misconduct.

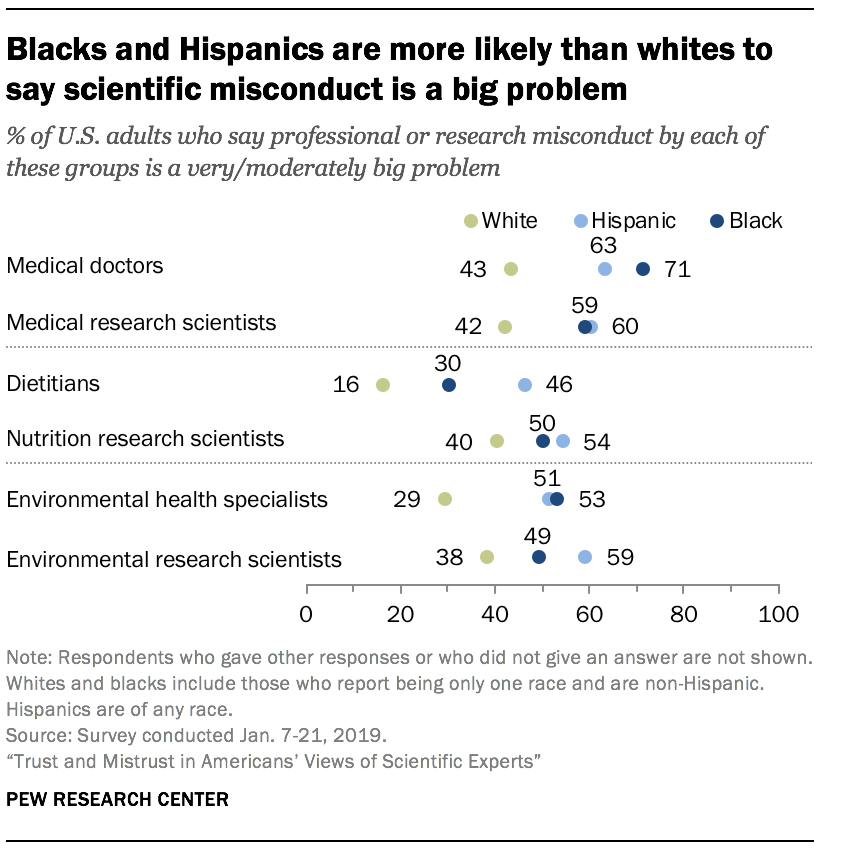

Together, their responses provide a rich and complex portrait of trust in scientists, suggesting that the public generally has more confidence in practitioners than researchers and that greater familiarity with these groups, as well as greater factual knowledge about science, correlates with higher levels of trust. But there is widespread skepticism of scientists when it comes to issues of transparency and accountability for mistakes. The survey also highlights concerns about misconduct, with black and Hispanic respondents more likely than whites to see it as a big problem.

Americans are often more trusting of dietitians and medical doctors than of nutrition and medical researchers, respectively

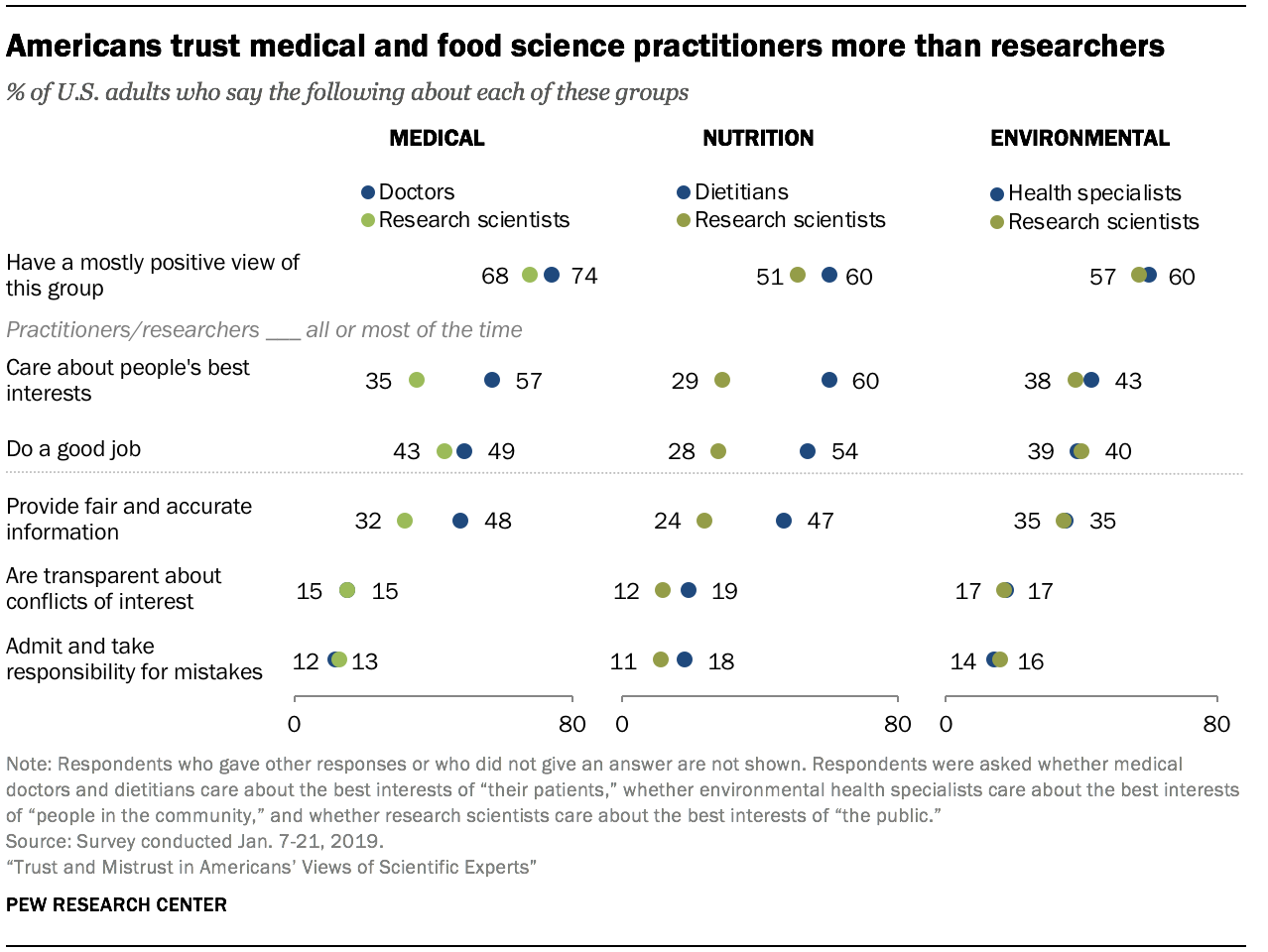

Overall, Americans tend to trust science practitioners, who directly provide treatments and recommendations to the public, more than researchers working in the same domains. Public trust in dietitians, for instance, is nearly double that of nutrition research scientists. Similarly, trust in medical doctors is considerably stronger than trust in medical research scientists.

For example, there are wide differences in the degree to which Americans see dietitians and nutrition researchers as competent in their jobs. A majority (54%) say dietitians do a good job providing recommendations about healthy eating all or most of the time, compared with 28% who say nutrition scientists do a good job conducting research all or most of the time.

In addition, 47% say dietitians provide fair and accurate information about their recommendations all or most of the time, compared with 24% for nutrition scientists discussing their research. Six-in-ten Americans (60%) think dietitians care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, while about half as many (29%) believe that about nutrition researchers when it comes to concern for the public.

Similarly, the public tends to view medical doctors more positively than medical researchers when it comes to their concern for the public’s interests and providing trustworthy information. For example, 57% of Americans say doctors care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, compared with 35% for medical researchers. About half the public (48%) believes that medical doctors provide fair and accurate treatment information all or most of the time, compared with 32% who say this about medical researchers in discussing their findings.

In contrast, public levels of trust in environmental health specialists and environmental research scientists are roughly the same. For instance, 39% of U.S. adults say environmental health specialists do a good job versus 40% for researchers, and 35% say each provides fair and accurate information all or most of the time.

Most say scientists routinely lack transparency and accountability, but views about misconduct vary

Integrity in research and practice is often considered foundational for public trust in science. The Center’s survey finds most Americans tend to be skeptical of both practitioners and researchers when it comes to potential sources of mistrust.

Integrity in research and practice is often considered foundational for public trust in science. The Center’s survey finds most Americans tend to be skeptical of both practitioners and researchers when it comes to potential sources of mistrust.

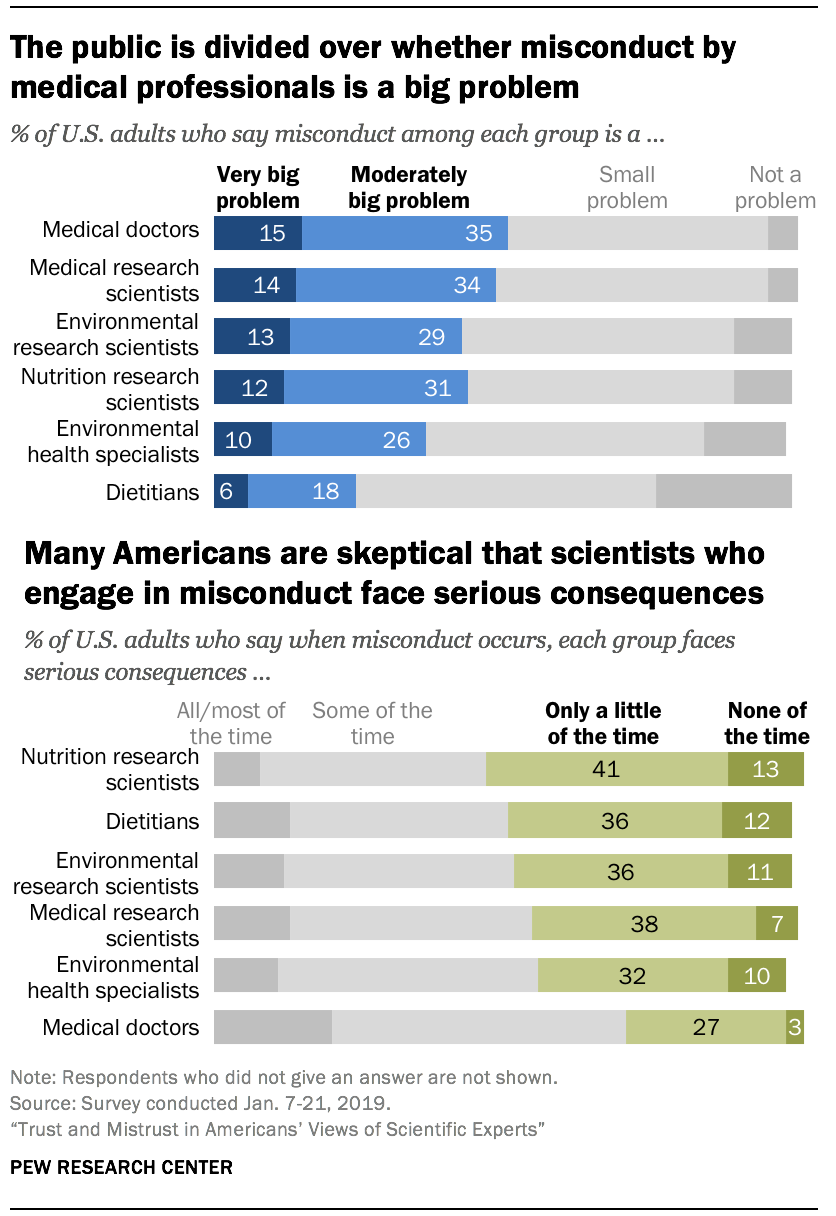

No more than 19% say that scientists across these six specialties are transparent in revealing potential conflicts of interest with industry all or most of the time. A larger share – ranging from 27% to 37% – believes scientists are transparent only a little or none of the time. Similarly, fewer than two-in-ten Americans say that scientists admit and take responsibility for their mistakes all or most of the time.

Americans vary in their assessments of whether misconduct is a big problem for scientists. There is relatively more concern about misconduct among medical professionals; about half of U.S. adults say misconduct is at least a “moderately big” problem among medical doctors (50%) and medical researchers (48%). The public is less concerned about misconduct among dietitians (24% call it a very or moderately big problem). Judgments about misconduct among the other scientific groups fall somewhere in between.

To the extent that such problems occur, the public is generally skeptical that scientists typically face serious consequences for misconduct. No more than two-in-ten say scientists from any of the six specialties face serious consequences for misconduct all or most of the time.

Roughly four-in-ten or more U.S. adults say nutrition researchers (53%), dietitians (47%), environmental researchers (48%), medical researchers (45%) and environmental health specialists (42%) face serious consequences for misconduct “only a little” or “none of the time.” By comparison, only 30% say medical doctors rarely face consequences for professional misbehavior.

Public trust in scientists is linked with familiarity of their work and factual knowledge about science

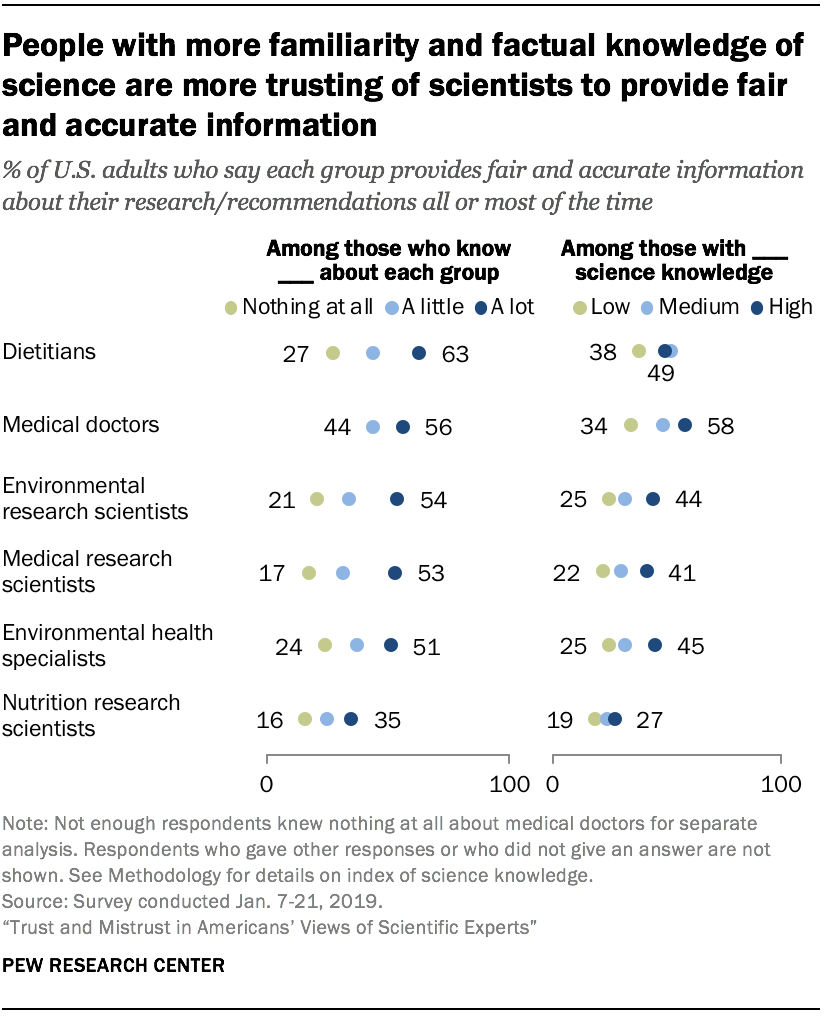

People’s level of familiarity with scientists and their level of factual knowledge about science can be consequential for public trust in scientists, the Center’s survey finds. A key challenge for science communication has long centered around the relative invisibility of scientists and their work. Those who report knowing more about the work of scientists have more positive and more trusting views about them.

In addition, people with higher levels of factual knowledge about science tend to hold more positive and trusting views of scientists. (It is important to note that familiarity with scientists is not the same as factual science knowledge.)

These factors, however, have a more limited effect on public skepticism about how often scientists are transparent about potential conflicts of interest, admit to mistakes or are held accountable for misconduct.

Americans learn about scientists from a range of information sources

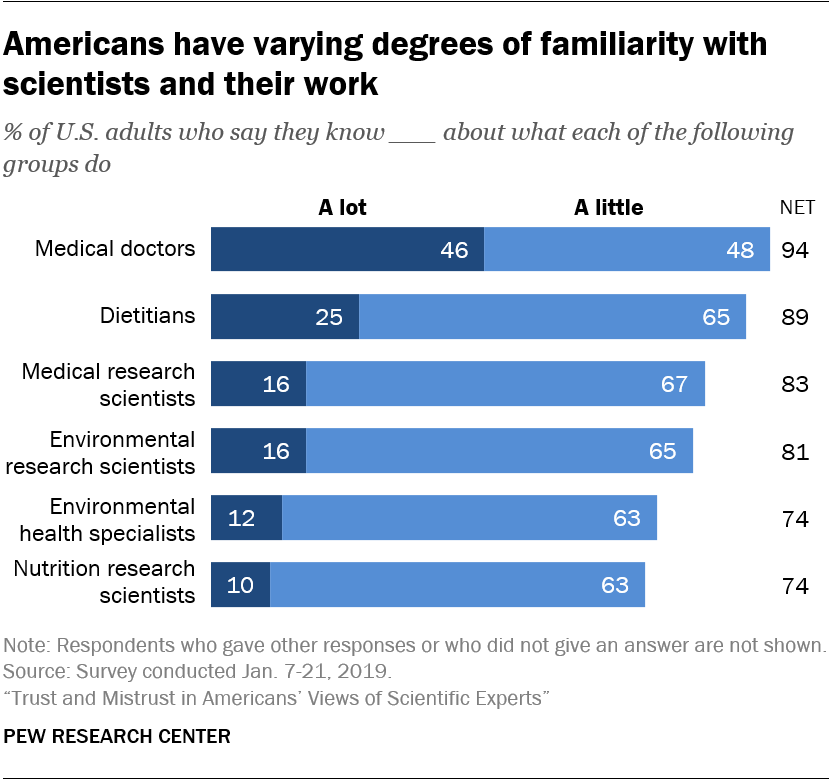

The Center’s survey finds a wide range of familiarity with scientists. Some 46% of U.S. adults say they know a lot about what medical doctors do, another 48% say they know “a little” and only 6% say they know “nothing at all.” In contrast, just 10% of U.S. adults report knowing a lot about what nutrition research scientists do, while most know a little (63%) and about a quarter (26%) say they know nothing at all.

The Center’s survey finds a wide range of familiarity with scientists. Some 46% of U.S. adults say they know a lot about what medical doctors do, another 48% say they know “a little” and only 6% say they know “nothing at all.” In contrast, just 10% of U.S. adults report knowing a lot about what nutrition research scientists do, while most know a little (63%) and about a quarter (26%) say they know nothing at all.

Familiarity with these specialties stems from a range of information sources. News reports are the most common source. Majorities of Americans say they know at least a little about each of these scientists because they have heard or read about their work in the news. Personal contact with these groups varies from 65% for medical doctors to 16% for nutrition research scientists. Other potential sources of information about scientists considered in the survey include school and work.

People who have higher levels of familiarity with scientists’ work are more confident that scientists can be counted on to do their job with competence, to show concern for the public and to provide accurate information. One example: 63% of those who know a lot about dietitians say they provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time, compared with 27% of those who know nothing about dietitians − a difference of 36 percentage points.

People who have higher levels of familiarity with scientists’ work are more confident that scientists can be counted on to do their job with competence, to show concern for the public and to provide accurate information. One example: 63% of those who know a lot about dietitians say they provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time, compared with 27% of those who know nothing about dietitians − a difference of 36 percentage points.

There is a less pronounced tendency for people with high factual science knowledge to trust scientists more than those with low science knowledge. Note that factual science knowledge is not the same as familiarity with each profession.[2. An exploratory factor analysis suggests that familiarity measures and science knowledge items do not map onto a single, underlying dimension. Instead, the analysis finds a two-factor solution. One underlying factor is closely correlated with the factual science knowledge items and the second factor is closely correlated with the self-perceived familiarity with scientists. These findings are in keeping with past research on these concepts. For example, Ladwig, Pete, Kajsa E. Dalrymple, Dominique Brossard, Dietram A. Scheufele, and Elizabeth A. Corley, 2012, “Perceived familiarity or factual knowledge? Comparing operationalizations of scientific understanding,” Science and Public Policy found that predictors of self-perceived familiarity and factual science knowledge tend to differ. Rose, Kathleen M., Emily L. Howell, Leona Y.-F Su, Michael A. Xenos, Dominque Brossard and Dietram A. Scheufele, 2019, “Distinguishing scientific knowledge: The impact of different measures of knowledge on genetically modified food attitudes,” Public Understanding of Science highlights differences in the relationship between self-perceived familiarity and factual science knowledge in predicting people’s views about genetically modified foods.]

Partisan differences in overall views and trust in scientists occur primarily for environmental scientists

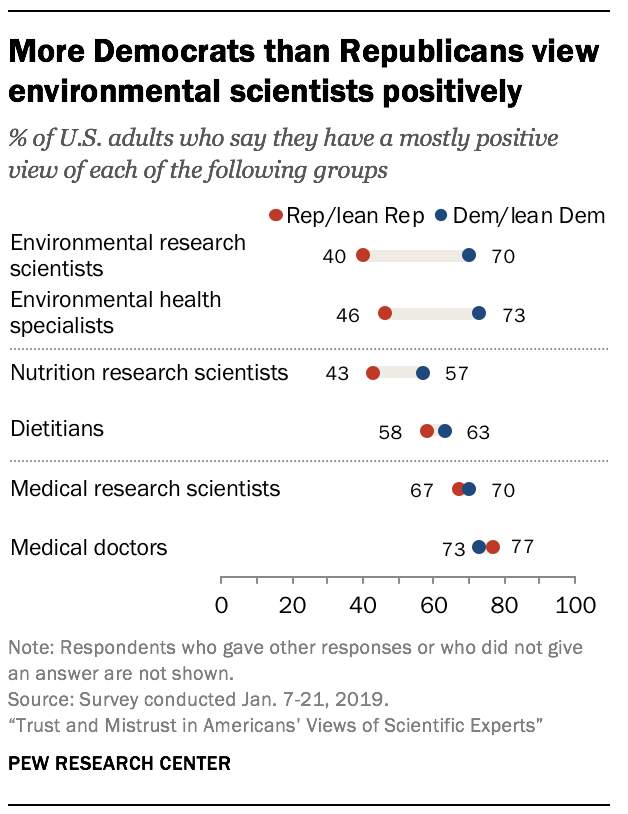

There are political differences in people’s views about scientists for some, but not all, specialties. In particular, wide political differences emerge in public support for and trust of environmental researchers and environmental health specialists.

Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party have more favorable views of environmental researchers and environmental health specialists than their Republican and Republican-leaning counterparts. For example, 70% of Democrats have a positive view of environmental researchers compared with 40% of Republicans.

Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party have more favorable views of environmental researchers and environmental health specialists than their Republican and Republican-leaning counterparts. For example, 70% of Democrats have a positive view of environmental researchers compared with 40% of Republicans.

Democrats are also more inclined than Republicans to have overall positive views of nutrition research scientists, although the magnitude of difference is modest by comparison (57% vs. 43%, respectively).

There are no significant differences by political party in views of medical researchers, medical doctors or dietitians.

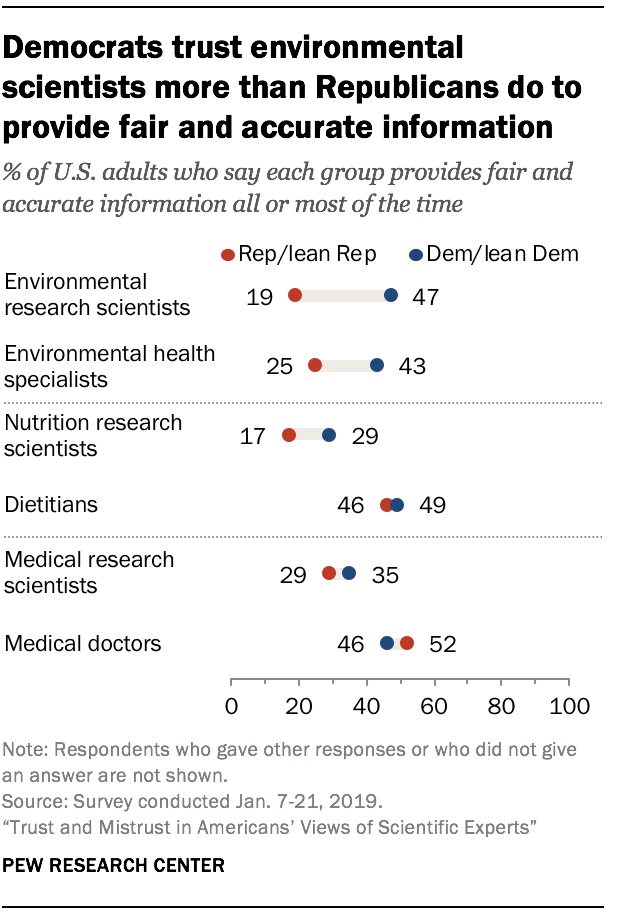

Similarly, Democrats are more trusting of environmental scientists than Republicans when it comes to their competence, concern for the public and the accuracy of information they provide. For instance, 47% of Democrats trust environmental scientists to provide fair and accurate information about their work all or most of the time, compared with 19% of Republicans.

Similarly, Democrats are more trusting of environmental scientists than Republicans when it comes to their competence, concern for the public and the accuracy of information they provide. For instance, 47% of Democrats trust environmental scientists to provide fair and accurate information about their work all or most of the time, compared with 19% of Republicans.

There are modest partisan differences when it comes to trust in nutrition research scientists, but both party groups have about the same levels of trust in medical doctors, medical researchers and dietitians.

And party groups tend to share skeptical views of scientists’ transparency, responsibility for mistakes and accountability for misconduct.

Blacks, Hispanics more likely than whites to consider scientific misconduct a big problem

Black and Hispanic adults stand out as more likely than whites to see professional or research misconduct as a very or moderately big problem.

A large majority of black Americans (71%) say misconduct by medical doctors is a very/moderately big problem, compared with 43% of whites – a gap of 28 percentage points. Hispanics (63%) are also more likely than whites to describe doctors’ misconduct as a big problem. In addition, a larger percentage of blacks (59%) and Hispanics (60%) say misconduct by medical research scientists is a very big or moderately big problem, compared with 42% of whites.

A large majority of black Americans (71%) say misconduct by medical doctors is a very/moderately big problem, compared with 43% of whites – a gap of 28 percentage points. Hispanics (63%) are also more likely than whites to describe doctors’ misconduct as a big problem. In addition, a larger percentage of blacks (59%) and Hispanics (60%) say misconduct by medical research scientists is a very big or moderately big problem, compared with 42% of whites.

These findings could be related to inequities in health care and outcomes, among other issues faced by black people and other nonwhite Americans in medical treatment and research. Examples include the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male”2 and the case of Henrietta Lacks, both of which involved individuals who were subject to research studies without their knowledge or consent.