Most Americans have positive overall views of medical doctors and medical research scientists. But they have more mixed assessments when it comes to trust-related judgments, especially for medical researchers. Fewer than half the public believes medical researchers do a good job, provide fair and accurate information about their findings or care about the public interest all or most of the time. Public trust in medical doctors is higher by comparison.

About half of the public sees misconduct by medical researchers or doctors as at least a moderately big problem; many are skeptical that misconduct, particularly that by medical researchers, usually leads to serious consequences.

About half of the public sees misconduct by medical researchers or doctors as at least a moderately big problem; many are skeptical that misconduct, particularly that by medical researchers, usually leads to serious consequences.

People less familiar with the role of these medical professionals and those with lower levels of science knowledge are generally more critical of both medical doctors and researchers. Blacks and Hispanics stand out as more likely than whites to see misconduct among medical doctors and researchers as a big problem.

[callout]Medical doctors and medical research scientists

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of May 2018, the U.S. had an estimated 679,280 medical doctors and 120,320 medical research scientists.

The Center’s survey asked respondents about either medical doctors or medical research scientists. Respondents were given brief definitions prior to answering questions about each group. These were:

– “Medical doctors provide patients with diagnoses of disease and/or treatment recommendations to promote, maintain or restore a patient’s health.”

– “Medical research scientists conduct research to investigate human diseases, and test methods to prevent and treat them.”

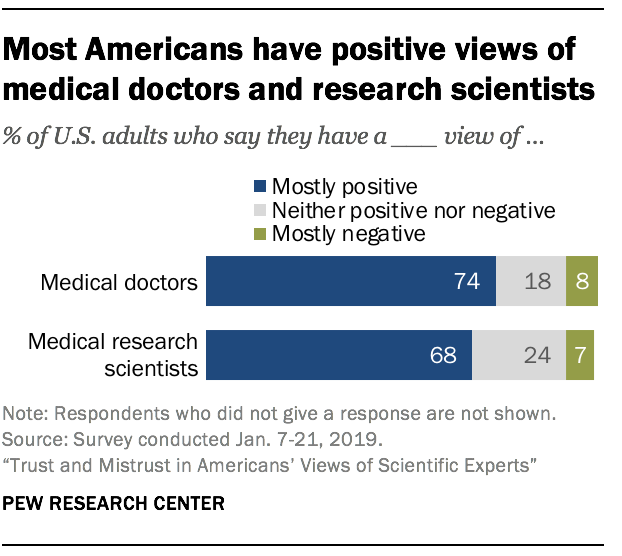

[/callout]About three-quarters (74%) of Americans say they have positive views of medical doctors, while just 8% say they have negative views. Another 18% say their opinion of doctors is neutral. A sizable majority (68%) sees medical research scientists in an overall positive light. A small share of Americans (7%) view them negatively, and 24% have a mixed view.

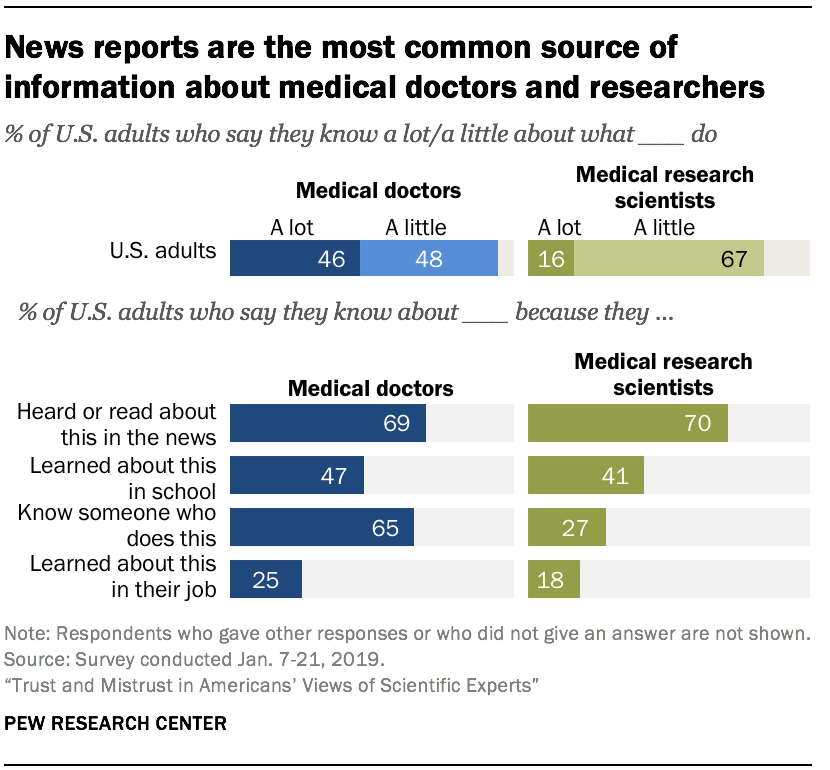

Americans say they have some familiarity with the work of medical practitioners and researchers. The vast majority say they know either a little (48%) or a lot (46%) about what medical doctors do. A smaller percentage of the public is at least somewhat familiar with what medical research scientists do: Two-thirds say they know a little (67%), and another 16% say they know a lot.

The news media is the most common source of information about these specialties, the survey shows. A large majority of Americans say they are familiar with medical doctors (69%) or medical research scientists (70%) because they have heard or read about their work in the news.

The news media is the most common source of information about these specialties, the survey shows. A large majority of Americans say they are familiar with medical doctors (69%) or medical research scientists (70%) because they have heard or read about their work in the news.

Not surprisingly, many Americans (65%) say they have learned about what medical doctors do through knowing a practitioner personally. Far fewer adults (27%) say they are familiar with the work of medical research scientists because of a personal relationship.

Other sources of information about medical professionals include school (47% medical doctors and 41% for medical researchers) or work (25% for doctors and 18% for medical researchers).

More Americans believe doctors than medical researchers care about people’s best interests all or most of the time

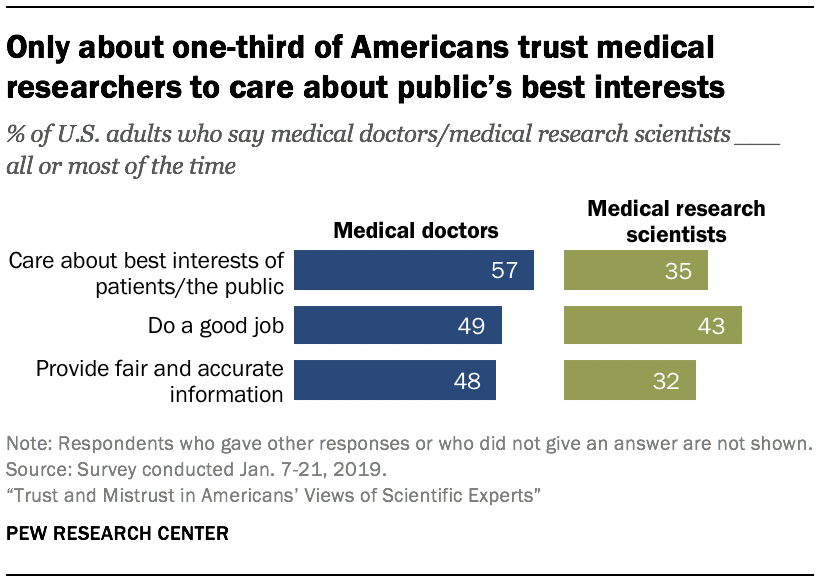

While most Americans hold an overall positive view of medical professionals, public trust in these doctors and researchers is mixed. People express less optimism about how often they can count on medical scientists to do a good job, to provide fair and accurate information, and to show concern for the public’s or patients’ interests, particularly when it comes to medical researchers versus doctors.

While most Americans hold an overall positive view of medical professionals, public trust in these doctors and researchers is mixed. People express less optimism about how often they can count on medical scientists to do a good job, to provide fair and accurate information, and to show concern for the public’s or patients’ interests, particularly when it comes to medical researchers versus doctors.

The majority of Americans (57%) say medical doctors care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time. A third (33%) say this occurs some of the time and 9% say this occurs only a little or none of the time. About half say medical doctors do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment recommendations (49%) or providing fair and accurate information about their recommendations (48%) all or most of the time.

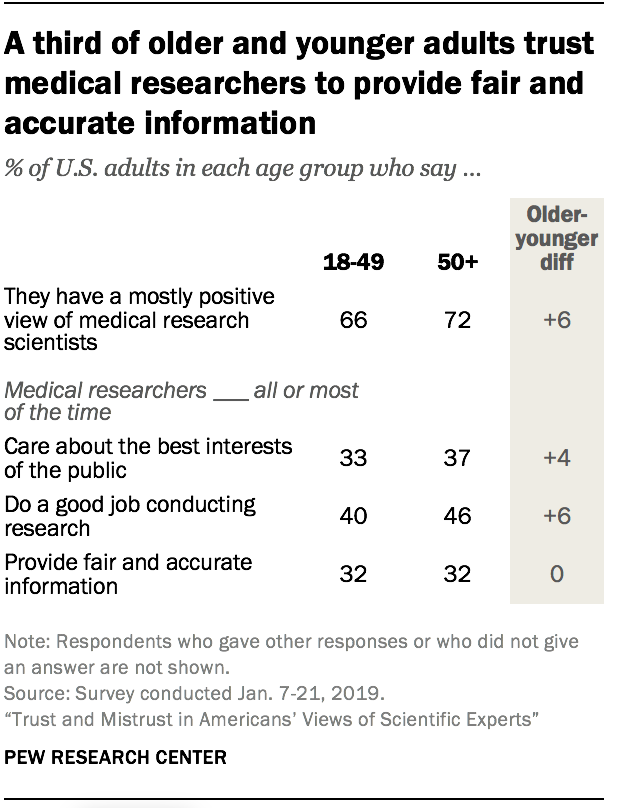

The public tends to have less trusting views when evaluating medical research scientists. About one-third (35%) say these researchers care about the best interests of the public all or most of the time, compared with 57% who say doctors care about patients. Americans also rate researchers more negatively than practitioners when it comes to the trustworthiness of their information; about one-third (32%) say medical research scientists provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time, compared with 48% for doctors. Of these three criteria, medical research scientists receive the highest marks for their perceived competence: 43% of the public says researchers regularly do a good job conducting research.

People who are more familiar with physicians and medical researchers and have high levels of factual science knowledge hold more positive views of those professions

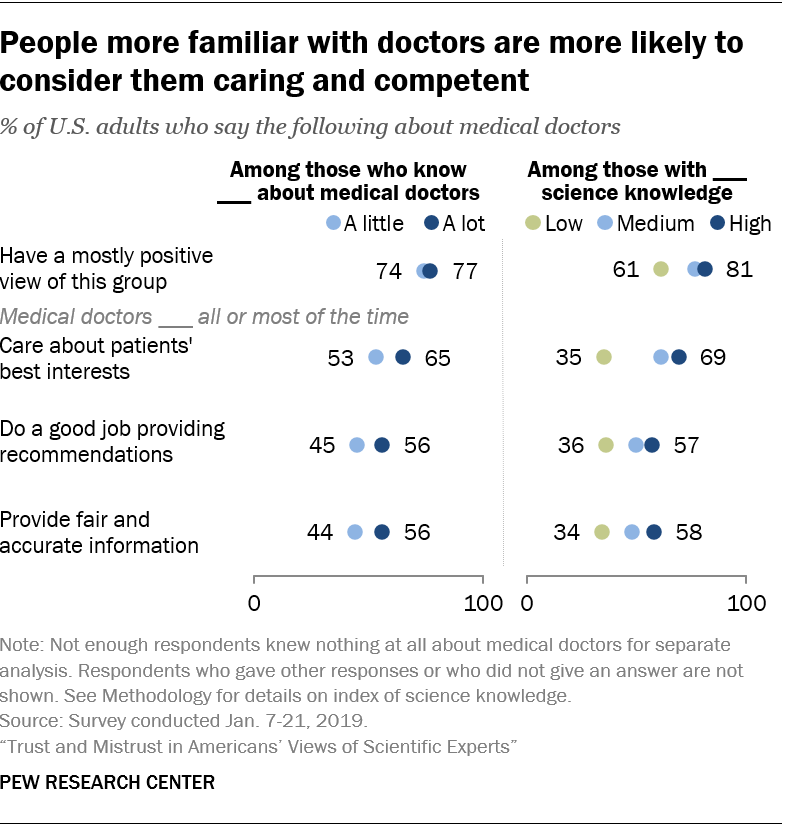

Roughly three-quarters of adults who say they know a lot (77%) or a little (74%) about what medical doctors do have a positive view of them. (The 6% of Americans who say they know nothing at all about the work of medical doctors do not make up a large enough group for separate analysis.)

Roughly three-quarters of adults who say they know a lot (77%) or a little (74%) about what medical doctors do have a positive view of them. (The 6% of Americans who say they know nothing at all about the work of medical doctors do not make up a large enough group for separate analysis.)

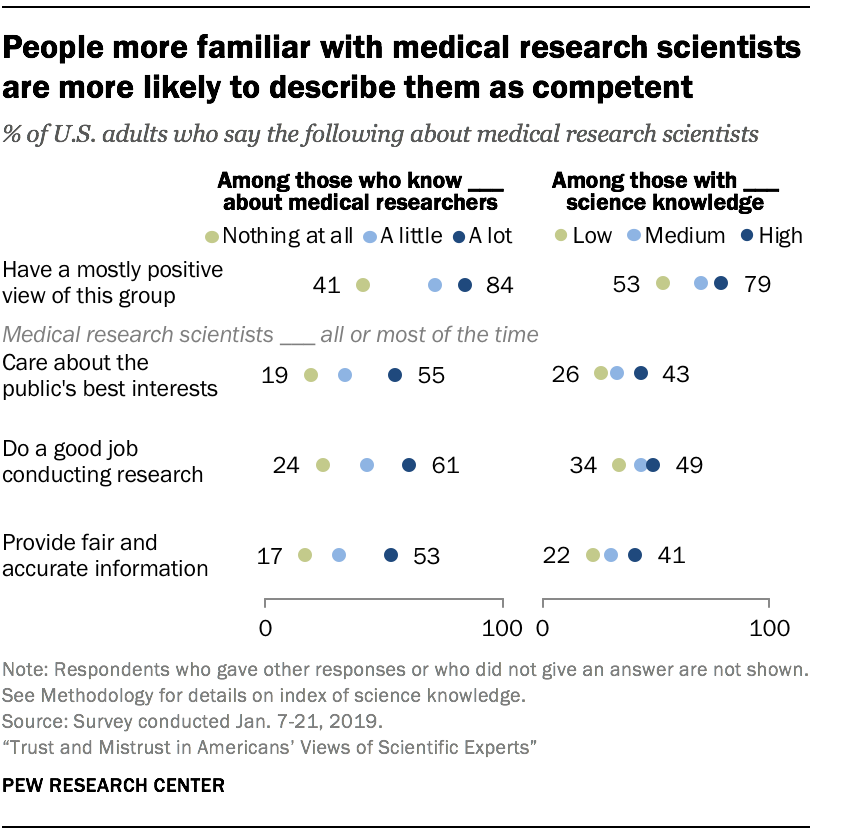

Among those who say they know a lot about the role of medical research scientists, 84% have a positive view. In contrast, 41% of those who say they do not know anything about medical research scientists have a positive opinion of them.

Trust-related judgments in terms of competence, accuracy of information and concern for the public also vary by people’s familiarity with the work of scientists. Among the 46% of U.S. adults who say they know a lot about the work of medical doctors, most say doctors routinely care about the best interests of their patients (65%), do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment information (56%) and provide fair and accurate information (56%). Trust in medical doctors is 11 to 12 percentage points lower on these assessments among those who report knowing a little about medical doctors.

Among the minority of Americans (16%) who say they know a lot about the work of medical researchers, most (61%) say they do a good job conducting research all or most of the time. People who know only a little or nothing about medical researchers’ work are less likely to say they routinely do a good job at it (43% and 24%, respectively). Familiarity with medical research also is related to how people view researchers’ empathy and ability to remain unbiased: Those who know a lot about medical research scientists are far more likely than people who know nothing to say medical researchers care about the public’s interests (55% vs. 19%, respectively) and provide fair and accurate information (53% vs. 17%) all or most of the time.

Factual science knowledge also correlates with Americans’ views of these professionals. Adults who have more general knowledge of science, based on an 11-item index, tend to hold more positive views of doctors and researchers and to see them as caring, competent and fair in providing information.

Factual science knowledge also correlates with Americans’ views of these professionals. Adults who have more general knowledge of science, based on an 11-item index, tend to hold more positive views of doctors and researchers and to see them as caring, competent and fair in providing information.

For example, 81% of those with high science knowledge have a positive view of medical doctors, compared with 61% of those with low science knowledge. About seven-in-ten Americans with high science knowledge (69%) believe doctors care about patients’ best interests all or most of the time, compared with 35% of those with low knowledge. And while majorities of high-knowledge Americans say doctors do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment recommendations and providing fair and accurate information, about one-third of people with low science knowledge say the same.

The same pattern is seen in Americans’ assessments of medical research scientists. Adults with high levels of factual science knowledge are overwhelmingly likely to have a positive view (79%) of medical researchers. Among those with low science knowledge, 53% say they have a positive view of medical researchers – a difference of 26 percentage points.

Those with low science knowledge are particularly skeptical of medical research scientists. For instance, 22% say medical researchers usually provide fair and accurate information about their research, compared with 41% of Americans with high knowledge. Americans with low levels of science knowledge are significantly more likely to say medical researchers provide fair and accurate information only a little or never (22%, vs. 7% of those with high science knowledge).

Older Americans express more trust in medical scientists

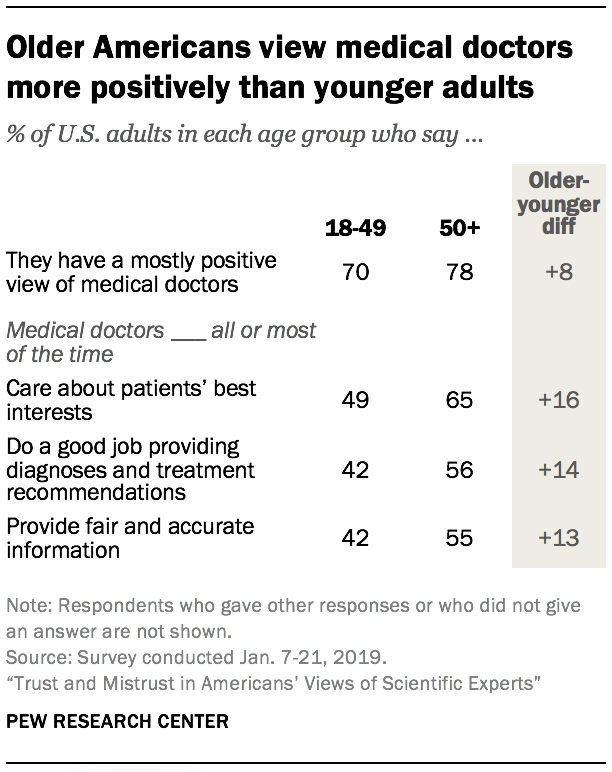

Americans ages 50 and older are more likely than younger adults to trust medical doctors and researchers. For example, about two-thirds (65%) of adults 50 and older say medical doctors care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, compared with about half (49%) of those under age 50. A majority of adults ages 50 and older (56%) say doctors routinely do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment options, compared with 42% of 18- to 49-year-olds who say the same.

Americans ages 50 and older are more likely than younger adults to trust medical doctors and researchers. For example, about two-thirds (65%) of adults 50 and older say medical doctors care about the best interests of their patients all or most of the time, compared with about half (49%) of those under age 50. A majority of adults ages 50 and older (56%) say doctors routinely do a good job providing diagnoses and treatment options, compared with 42% of 18- to 49-year-olds who say the same.

Differences by age in people’s views about medical doctors are significant even after controlling for people’s level of science knowledge and other demographics in statistical modeling.

Differences by age in people’s views about medical doctors are significant even after controlling for people’s level of science knowledge and other demographics in statistical modeling.

There are modest differences by age in assessments of medical research scientists.

Most Americans believe medical doctors and research scientists are rarely candid about potential conflicts of interest or making errors

Most Americans express some degree of skepticism as to whether physicians and medical researchers are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups. Few Americans (15%) say medical doctors are transparent about this all or most of the time. The same percentage of the public (15%) says this about medical research scientists. About twice as many believe medical professionals are transparent only a little or none of the time (33% and 34% for doctors and medical researchers, respectively).

Most Americans express some degree of skepticism as to whether physicians and medical researchers are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups. Few Americans (15%) say medical doctors are transparent about this all or most of the time. The same percentage of the public (15%) says this about medical research scientists. About twice as many believe medical professionals are transparent only a little or none of the time (33% and 34% for doctors and medical researchers, respectively).

Most Americans do not believe medical professionals usually admit and take responsibility for their mistakes: Just over one-in-ten say doctors (12%) or medical researchers (13%) do this all or most of the time. Almost half of the public says these groups take responsibility for their mistakes some of the time (46% and 48% for doctors and medical researchers, respectively), and about four-in-ten say doctors and medical research scientists take responsibility for their mistakes only a little or none of the time (41% and 38%, respectively).

Americans are closely divided over the extent to which misconduct is a big problem among medical professionals

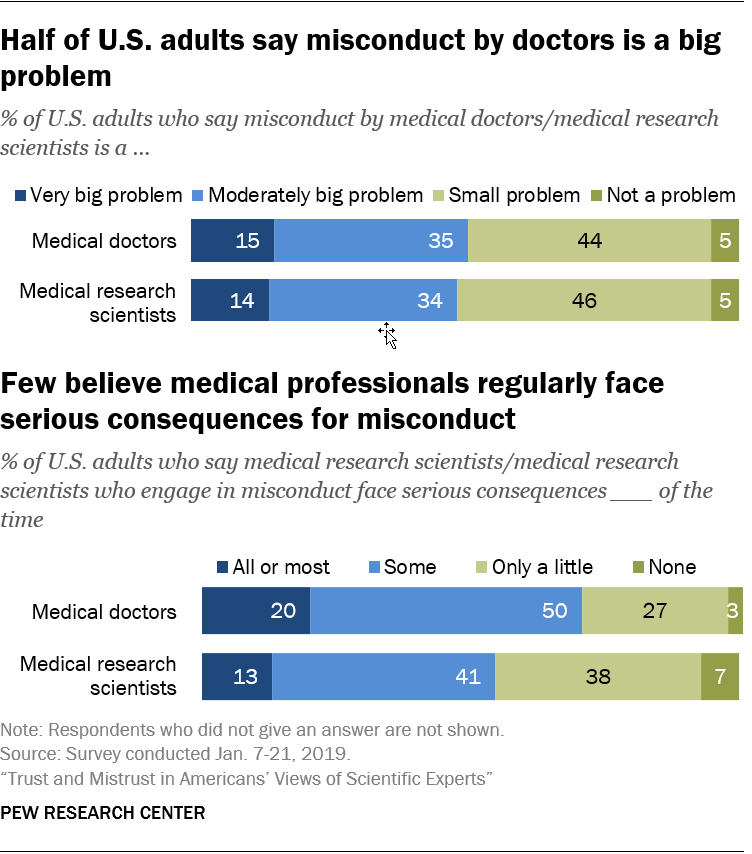

About half of adults consider misconduct among doctors or medical researchers to be at least a moderately big problem (50% and 48%, respectively). Just 5% say misconduct is not a problem for either group, while others consider it a small problem (44% and 46% for doctors and medical researchers, respectively).

About half of adults consider misconduct among doctors or medical researchers to be at least a moderately big problem (50% and 48%, respectively). Just 5% say misconduct is not a problem for either group, while others consider it a small problem (44% and 46% for doctors and medical researchers, respectively).

To the extent that misconduct occurs, the public is generally skeptical that scientists face serious consequences. Just two-in-ten (20%) U.S. adults say doctors who engage in professional misconduct face serious consequences all or most of the time, while 13% say the same about medical scientists who engage in research misconduct.

Sizable shares of Americans − 30% for medical doctors and 45% for medical researchers − believe these groups face serious consequences for misconduct only a little or none of the time.

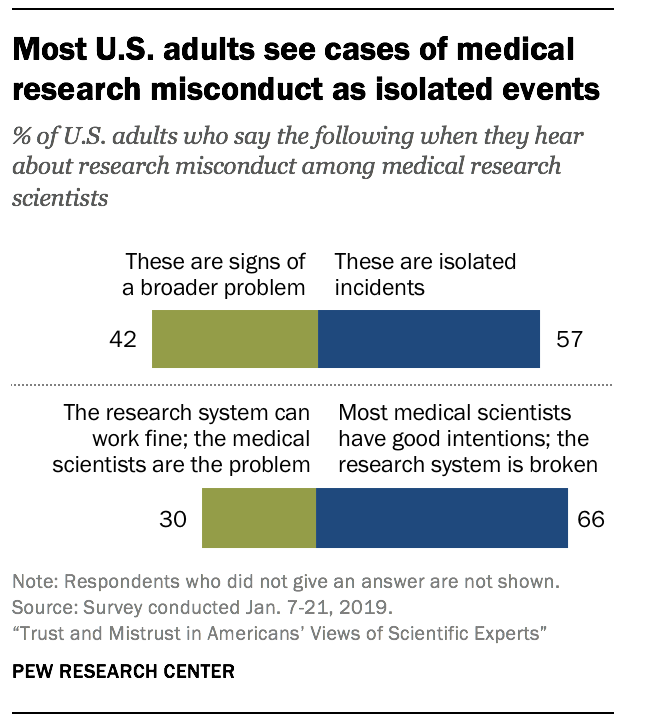

In thinking of news stories about misconduct, most Americans maintain an overall positive view of medical research in the U.S. Some 57% of Americans say they think of these stories as isolated incidents, rather than signs of a broader problem (42%). Public views about misconduct by doctors are similar. Six-in-ten (60%) say they usually consider news about misconduct as isolated incidents, while 39% see it as indicative of a broader problem.

In thinking of news stories about misconduct, most Americans maintain an overall positive view of medical research in the U.S. Some 57% of Americans say they think of these stories as isolated incidents, rather than signs of a broader problem (42%). Public views about misconduct by doctors are similar. Six-in-ten (60%) say they usually consider news about misconduct as isolated incidents, while 39% see it as indicative of a broader problem.

Even when misconduct occurs, most Americans report giving scientists the benefit of the doubt. Two-thirds (66%) say that when they hear about research misconduct they believe the medical researchers have good intentions, while 30% see the researchers as the problem.

The patterns are similar for views of medical doctors. A large majority (72%) say most doctors have good intentions, and 26% say doctors are the problem.

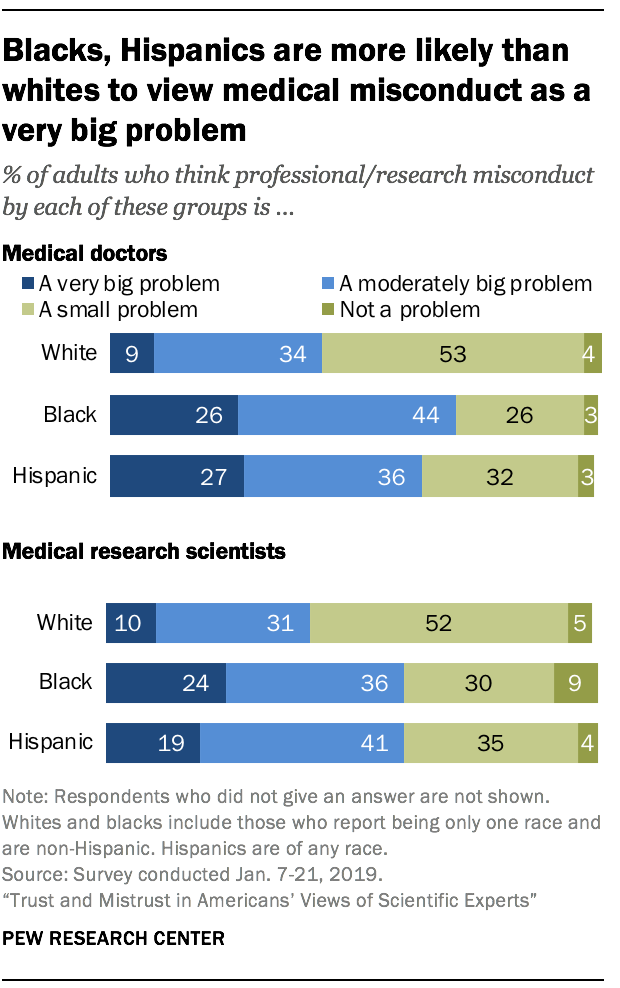

Black and Hispanic U.S. adults are more likely than whites to consider misconduct a big problem for medical doctors and medical researchers.

Black and Hispanic U.S. adults are more likely than whites to consider misconduct a big problem for medical doctors and medical researchers.

Majorities of blacks (71%) and Hispanics (63%) say professional misconduct by doctors is at least a moderately big problem. This includes about one-quarter of each group who say it is a very big problem (26% and 27%, respectively). In contrast, 43% of whites say medical misconduct is a very (9%) or moderately big (34%) problem.

There are similar race- and ethnicity-related differences in views of misconduct among medical researchers. Black (59%) and Hispanic (60%) adults are more likely than whites (42%) to say research misconduct by medical scientists is as at least a moderately big problem.

These findings could be related to a number of factors. (The differences persist in statistical models controlling for education, science knowledge and other factors.)4 Some have suggested that lingering concerns among black Americans over mistreatment, such as in the Tuskegee study, contributes to lower trust.5 And long-standing concerns about inequalities in health outcomes for blacks and Hispanics as compared with whites could play a role in these perceptions.