Majorities of U.S. adults have positive overall views of environmental health specialists and environmental research scientists. But public views are less rosy when it comes to key facets of trust, including how often these environmental scientists – whether researchers or health specialists – are competent at their jobs, provide accurate information or show concern for the public interest. Perceptions of environmental researchers tend to be similar to those for environmental health specialists, a relatively small occupational group that offers advice to organizations about potential health hazards in the environment such as air or water pollution.

Majorities of U.S. adults have positive overall views of environmental health specialists and environmental research scientists. But public views are less rosy when it comes to key facets of trust, including how often these environmental scientists – whether researchers or health specialists – are competent at their jobs, provide accurate information or show concern for the public interest. Perceptions of environmental researchers tend to be similar to those for environmental health specialists, a relatively small occupational group that offers advice to organizations about potential health hazards in the environment such as air or water pollution.

Democrats are more trusting of environmental researchers and environmental health specialists than are Republicans. But both political groups tend to be skeptical of environmental scientists when it comes to transparency and accountability for mistakes.

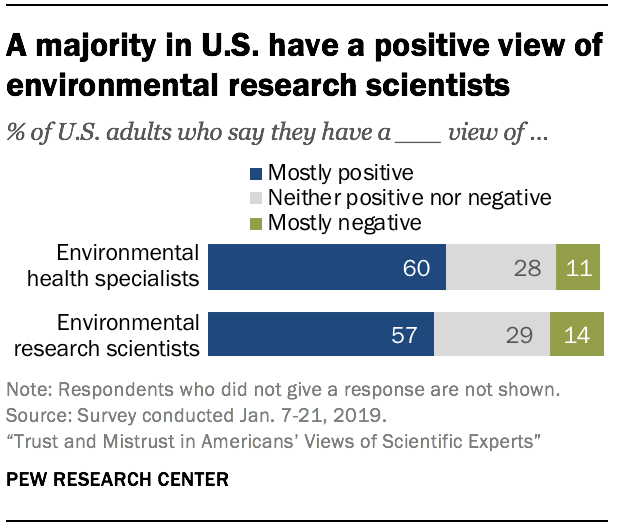

Some 60% of Americans say they have a mostly positive view of environmental health specialists. A similar share (57%) has a positive view of environmental researchers.

[callout]Environmental health specialists and environmental research scientists

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that 80,480 adults were employed in occupations listed as “environmental scientists and specialists, including health” as of May 2018.

The Center’s survey asked respondents about either environmental health specialists or environmental research scientists. Respondents were given brief definitions prior to answering questions about each group. These were:

“Environmental health specialists often advise organizations in a local community about environmental risks to human health such as air and water pollution and how to clean up polluted areas.”

“Environmental research scientists conduct research on the environment and how plants, animals and other organisms are affected by it.”

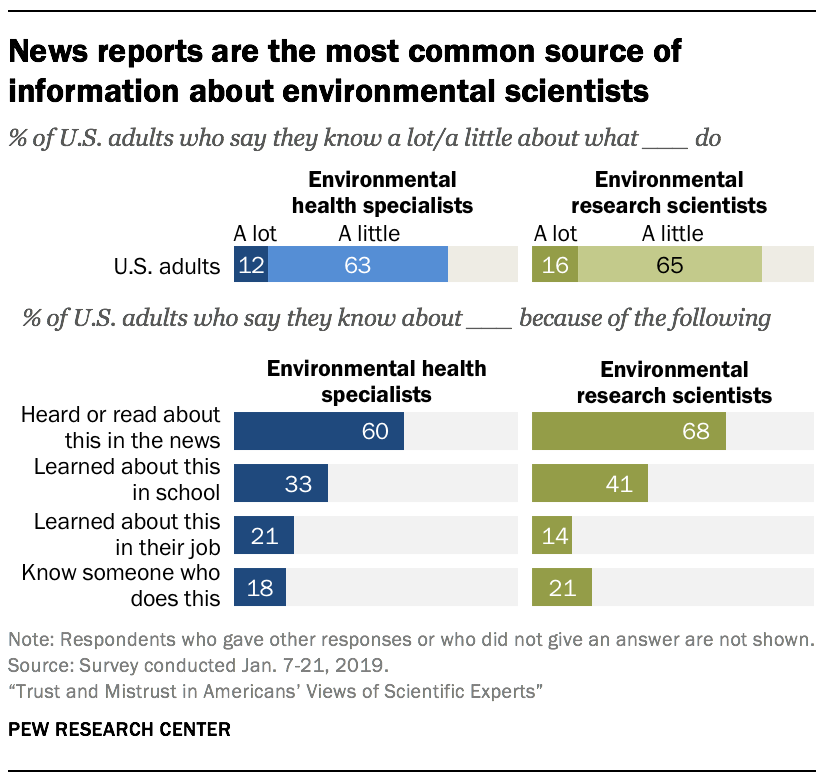

[/callout] Most Americans say they know at least a little about what environmental research scientists (81%) or environmental health specialists (74%) do. But only 16% say they know a lot about the work of environmental research scientists and just 12% say they know a lot about environmental health specialists.

Most Americans say they know at least a little about what environmental research scientists (81%) or environmental health specialists (74%) do. But only 16% say they know a lot about the work of environmental research scientists and just 12% say they know a lot about environmental health specialists.

The most common way for Americans to say they learn about these science-related occupations is through the news. About two-thirds of Americans (68%) say they know at least a little about environmental research scientists through news reports, and six-in-ten say they know about environmental health specialists through the news. Smaller percentages say they know about environmental research scientists or environmental health specialists through school, work or personal contact.

Roughly a third of Americans say environmental scientists can be relied on to provide fair, accurate information about their research

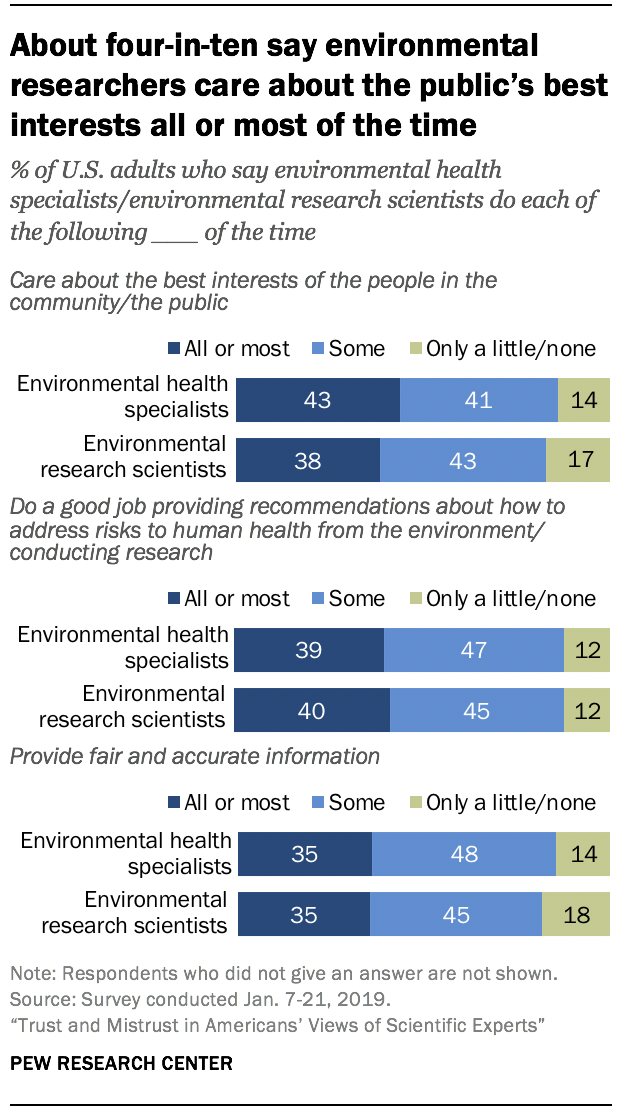

Public trust in environmental researchers and environmental health specialists appears to be generally lukewarm. The Center’s survey finds 43% of Americans believe environmental health specialists care about the best interests of the public all or most of the time. About four-in-ten (39%) say environmental health specialists do a good job providing recommendations about how to address risks to human health all or most of the time. And a slightly smaller percentage (35%) says environmental health specialists provide fair and accurate information about their recommendations all or most of the time.

Public trust in environmental researchers and environmental health specialists appears to be generally lukewarm. The Center’s survey finds 43% of Americans believe environmental health specialists care about the best interests of the public all or most of the time. About four-in-ten (39%) say environmental health specialists do a good job providing recommendations about how to address risks to human health all or most of the time. And a slightly smaller percentage (35%) says environmental health specialists provide fair and accurate information about their recommendations all or most of the time.

Americans have similarly tepid views of environmental research scientists. For example, 35% say environmental research scientists provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time, equal to the share who say this about environmental health specialists.

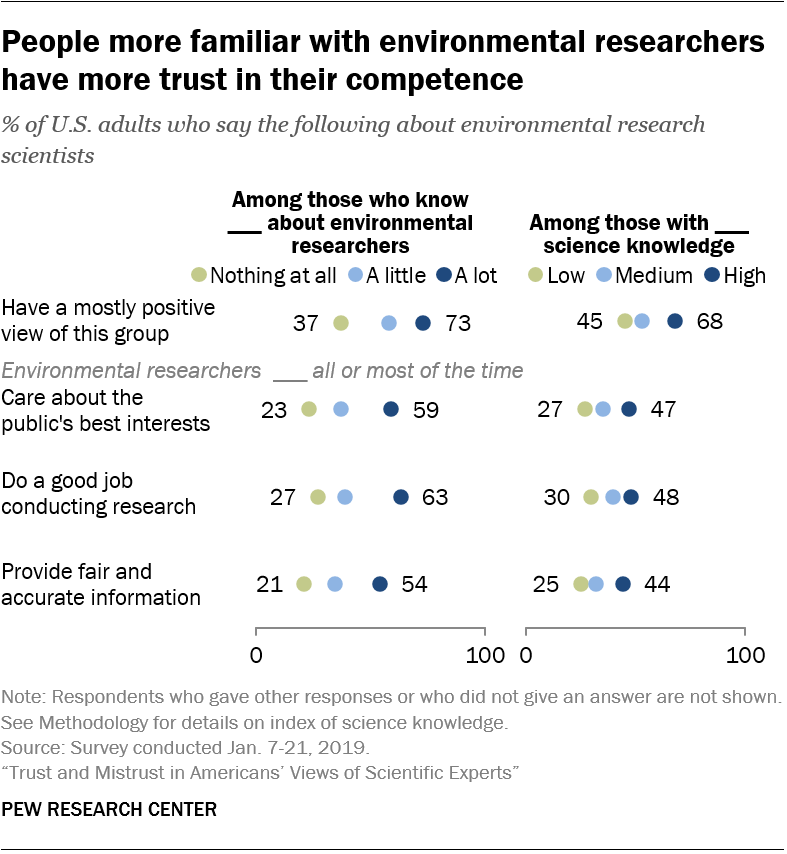

People more familiar with environmental health specialists, research scientists have more confidence these groups routinely provide fair and accurate information

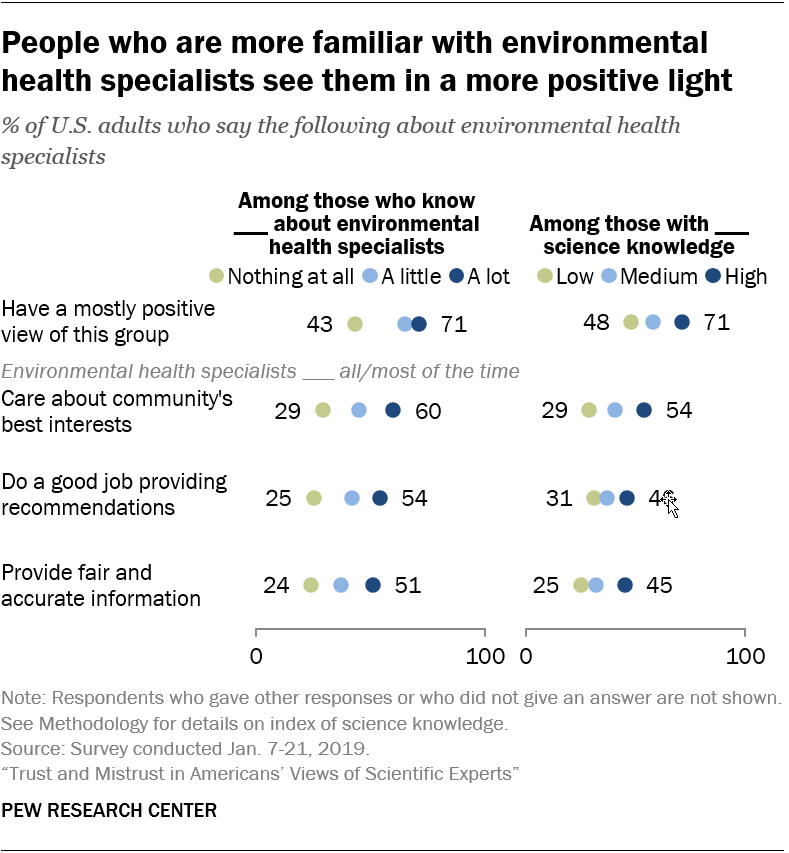

Those who are more familiar with environmental health specialists and environmental researchers have more positive and trusting views about them. For example, a 71% majority of those who know a lot about environmental health specialists say they have a positive view of this group. In contrast, 43% of those who know nothing at all about environmental health specialists say they have a mostly positive view of this group.

Those who are more familiar with environmental health specialists and environmental researchers have more positive and trusting views about them. For example, a 71% majority of those who know a lot about environmental health specialists say they have a positive view of this group. In contrast, 43% of those who know nothing at all about environmental health specialists say they have a mostly positive view of this group.

Those who are more familiar with these environmental science occupations also tend to trust people who hold them more than those who lack familiarity. For example, some 54% of those who know a lot about environmental health specialists say they do a good job all or most of the time. In comparison, one-quarter of those who know nothing at all about environmental health specialists (25%) say they do a good job. Those who are very familiar with environmental health specialists also are more likely than those who are not to say these specialists care about the community’s best interests (60% vs. 29%, respectively) or to trust them to provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time (51% vs. 24%).

There is a similar connection between familiarity with environmental research scientists and trust-related judgments about them. For example, Americans who report knowing a lot about environmental research scientists are about twice as likely (63% vs. 27%) as those not familiar with them to say environmental researchers do a good job all or most of the time.

There is a similar connection between familiarity with environmental research scientists and trust-related judgments about them. For example, Americans who report knowing a lot about environmental research scientists are about twice as likely (63% vs. 27%) as those not familiar with them to say environmental researchers do a good job all or most of the time.

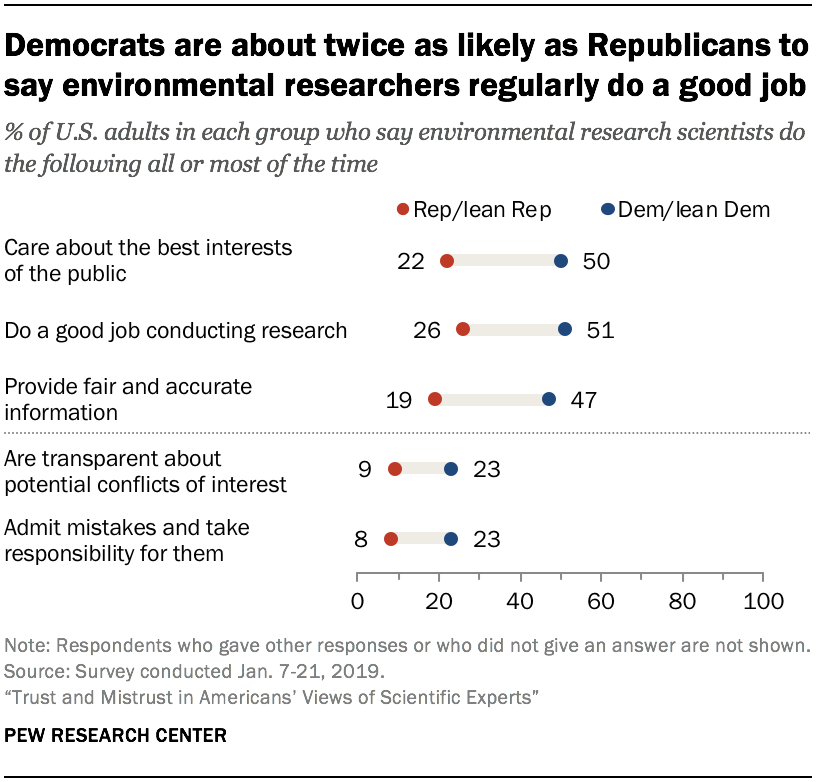

Democrats trust environmental research scientists more than Republicans do

Democrats are more trusting than Republicans of environmental health specialists and environmental research scientists. For example, about half of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (47%) say environmental research scientists provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time. In comparison, 19% of Republicans and independents leaning to the GOP agree. Democrats are also far more likely than Republicans to say environmental researchers care about the best interests of the public (50% vs. 22%) or do a good job conducting research (51% vs. 26%) all or most of the time.

Democrats are more trusting than Republicans of environmental health specialists and environmental research scientists. For example, about half of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (47%) say environmental research scientists provide fair and accurate information all or most of the time. In comparison, 19% of Republicans and independents leaning to the GOP agree. Democrats are also far more likely than Republicans to say environmental researchers care about the best interests of the public (50% vs. 22%) or do a good job conducting research (51% vs. 26%) all or most of the time.

There is a similar partisan difference in views of environmental health specialists.

Past Pew Research Center surveys have found wide political differences on attitudes related to the environment, climate change and energy. For instance, a 2016 survey showed large divides between Democrats and Republicans on judgments related to climate sciences.

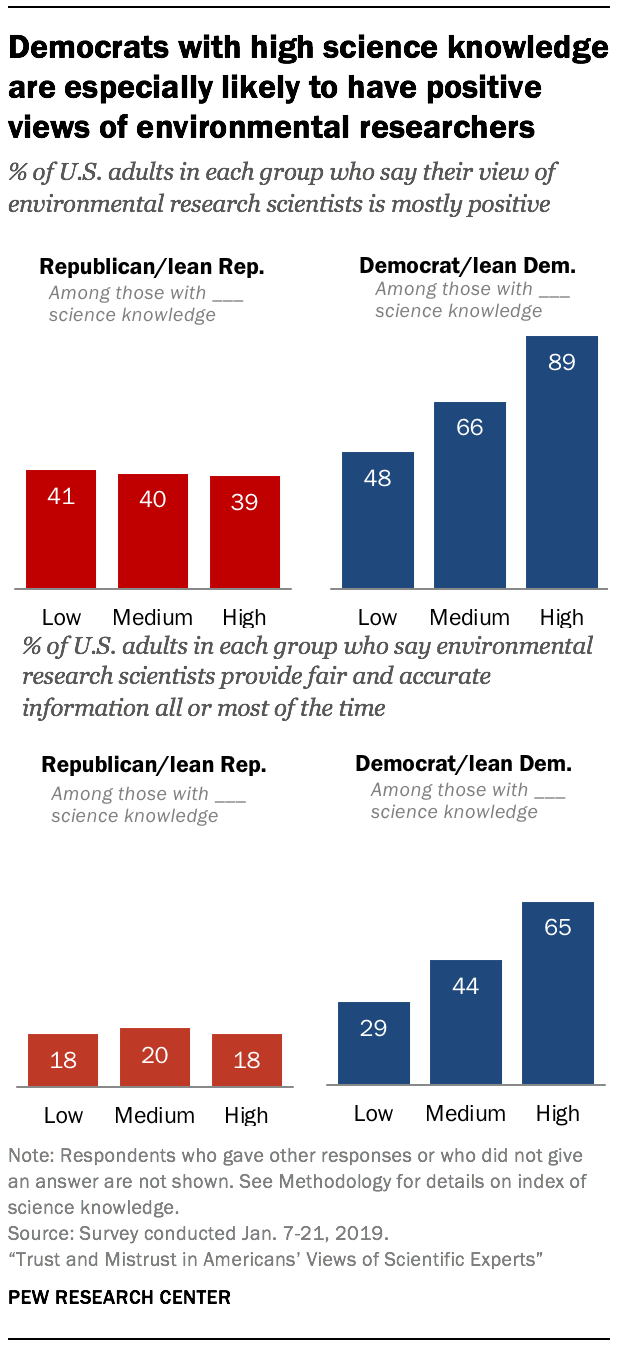

Science knowledge is closely related to trust judgments of environmental scientists among Democrats, but not Republicans

Among Democrats, those with high science knowledge are far more likely than those with low science knowledge to hold mostly positive views of environmental research scientists. About nine-in-ten Democrats with high science knowledge (89%) say their view of environmental research scientists is positive, compared with about half of Democrats with low science knowledge (48%). Among Republicans, those with high and low science knowledge are equally likely to say their view of environmental researchers is positive (39% and 41%, respectively).

Among Democrats, those with high science knowledge are far more likely than those with low science knowledge to hold mostly positive views of environmental research scientists. About nine-in-ten Democrats with high science knowledge (89%) say their view of environmental research scientists is positive, compared with about half of Democrats with low science knowledge (48%). Among Republicans, those with high and low science knowledge are equally likely to say their view of environmental researchers is positive (39% and 41%, respectively).

There is a similar relationship between science knowledge and political party when it comes to trust in these environmental scientists. For example, Democrats with high science knowledge are about twice as likely as Democrats with low science knowledge to say environmental research scientists give fair and accurate information about their research all or most of the time (65% vs. 29%). There are no differences among Republicans on how often environmental researchers can be relied on to provide fair and accurate information; 18% of those with both high and low science knowledge say environmental research scientists do this all or most of the time.

There is a similar pattern in views of environmental health specialists.

These findings are in keeping with the idea that the role of information in people’s judgments can depend on their identity as a partisan, a tendency known as motivated reasoning. Past Pew Research Center surveys have found a similar pattern on a range of views related to climate and energy issues.

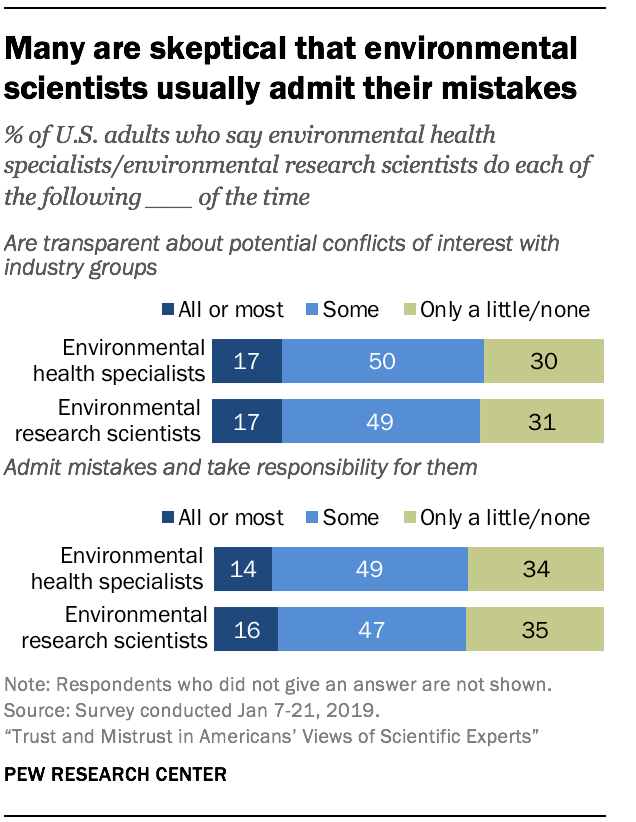

Fewer than two-in-ten are confident environmental health specialists or environmental research scientists are regularly transparent, accountable for mistakes

U.S. adults are skeptical that environmental health specialists or environmental researchers are regularly transparent about conflicts of interest or admit and take responsibility for mistakes.

Only 17% of Americans say environmental health specialists are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups all or most of the time. A larger share – 31% – says environmental health specialists are transparent a little or none of the time.

Only 17% of Americans say environmental health specialists are transparent about potential conflicts of interest with industry groups all or most of the time. A larger share – 31% – says environmental health specialists are transparent a little or none of the time.

Further, only 14% of U.S. adults say environmental health specialists admit and take responsibility for their mistakes all or most of the time, while 34% say environmental health specialists never or rarely admit mistakes.

The pattern is similar for environmental research scientists. For example, roughly one-third (35%) of Americans say environmental researchers rarely or never admit mistakes and take responsibility, similar to the share who say this about environmental health specialists.

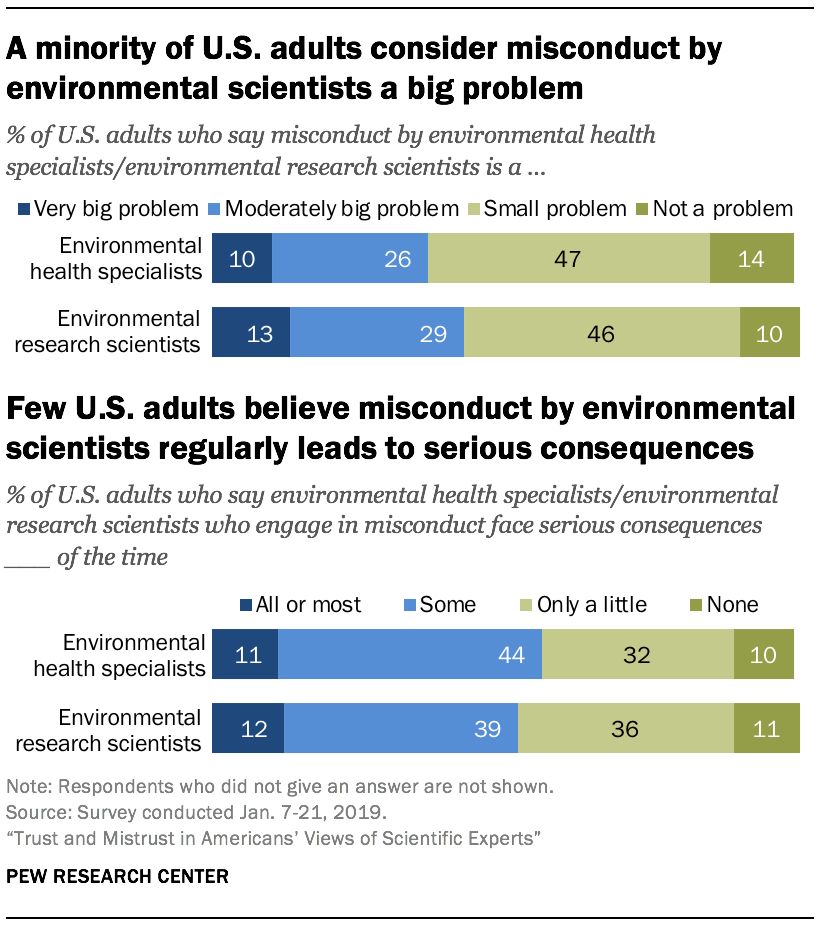

Less than half of the public thinks misconduct among these environmental science groups is at least a moderately big problem. Some 36% say misconduct is a very big or moderately big problem among environmental health specialists, while 43% say the same about misconduct among environmental research scientists.

Hispanic and black Americans are more likely than whites to see misconduct by environmental scientists as a big problem. For example, about six-in-ten Hispanics (59%) and half of blacks (49%) say research misconduct by environmental research scientists is at least a moderately big problem. In contrast, just 38% of whites say this.

Hispanic and black Americans are more likely than whites to see misconduct by environmental scientists as a big problem. For example, about six-in-ten Hispanics (59%) and half of blacks (49%) say research misconduct by environmental research scientists is at least a moderately big problem. In contrast, just 38% of whites say this.

Few Americans think misconduct routinely leads to serious consequences. Only 11% of Americans say environmental health specialists who engage in professional misconduct face serious consequences all or most of the time, while 42% believe there are serious consequences for misconduct only a little or none of the time. Views about the ramifications of misconduct among environmental researchers are similar.

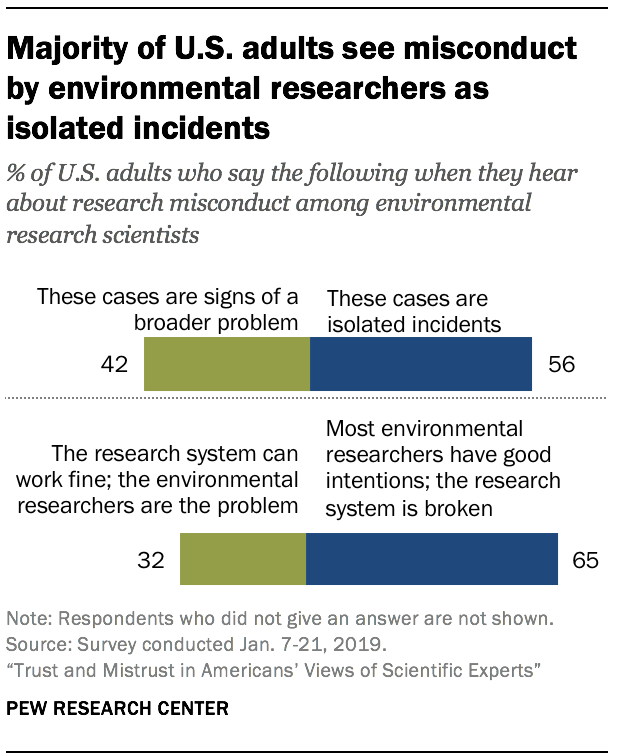

Most Americans give environmental research scientists the benefit of the doubt, saying they consider cases of misconduct as isolated incidents (56%) rather than signs of a broader problem (42%). About two-thirds (65%) say most environmental research scientists have good intentions but the system is broken, while one-third (32%) say the environmental researchers are the problem.

Most Americans give environmental research scientists the benefit of the doubt, saying they consider cases of misconduct as isolated incidents (56%) rather than signs of a broader problem (42%). About two-thirds (65%) say most environmental research scientists have good intentions but the system is broken, while one-third (32%) say the environmental researchers are the problem.

Views of misconduct by environmental health specialists are similar. Some 62% say they consider stories of misconduct to be isolated incidents, while 35% call them signs of a broader problem. About seven-in-ten (72%) believe most environmental health specialists have good intentions and blame systemic issues when misconduct occurs, while about a quarter (24%) blame the specialists for misconduct.