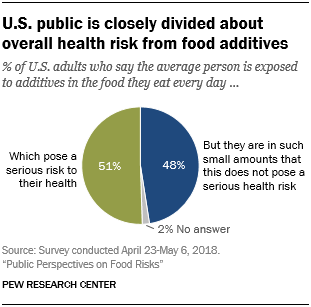

The American public is closely divided over the degree of health risk posed by additives present in the foods we regularly eat. Majorities see at least some risk from eating food produced with common agricultural and processing practices, including meat from animals given hormones or antibiotics, produce grown with pesticides and foods with artificial ingredients. And about half of the public says that foods with genetically modified (GM) ingredients are worse for one’s health than foods without, according to a new nationally representative survey from Pew Research Center.

The American public is closely divided over the degree of health risk posed by additives present in the foods we regularly eat. Majorities see at least some risk from eating food produced with common agricultural and processing practices, including meat from animals given hormones or antibiotics, produce grown with pesticides and foods with artificial ingredients. And about half of the public says that foods with genetically modified (GM) ingredients are worse for one’s health than foods without, according to a new nationally representative survey from Pew Research Center.

Today’s food landscape requires consumers to navigate shifting terrain given the flow of new food technologies and ongoing debates among food scientists, industry groups and health care professionals over which foods are safe and how what we eat can have a lasting impact on one’s health.

Today’s food landscape requires consumers to navigate shifting terrain given the flow of new food technologies and ongoing debates among food scientists, industry groups and health care professionals over which foods are safe and how what we eat can have a lasting impact on one’s health.

For instance, the American Academy of Pediatrics recently called for regulatory changes due to potential adverse effects on child development from food additives. And major food purveyors have been at odds over how to respond to consumer demand for healthier foods with more transparent labeling amid a changing regulatory environment.

The Pew Research Center survey finds the U.S. public of two minds about food additives. Roughly half say the average person faces a serious health risk from food additives over their lifetime (51%) while the other half believes the average person is exposed to potentially threatening additives in such small amounts that there is no serious risk (48%). It’s important to keep in mind that the survey asks respondents for their views about food additives as a whole. There are more than 10,000 additives used to enhance the shelf life, appearance, taste or nutritional value of foods, including over 3,000 that are “generally recognized as safe” – a term defined by the Food and Drug Administration, the main federal agency charged with regulating food safety.1

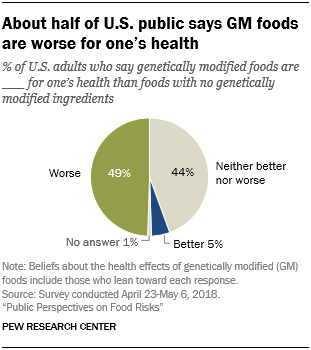

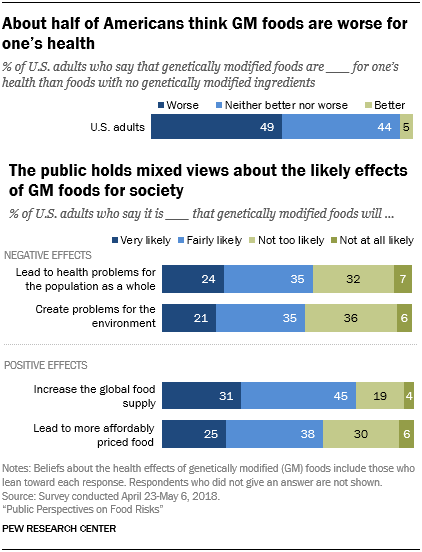

Seven-in-ten Americans (70%) believe that science has had a mostly positive effect on the quality of food in the United States. But when asked about one area where new developments in biotechnology are changing the possibilities for how we grow and consume foods, the public is closely divided. Roughly half of Americans (49%) believe that foods with GM ingredients are worse for one’s health than non-GM foods, while 44% say such foods are neither better nor worse and 5% say they are better for one’s health.

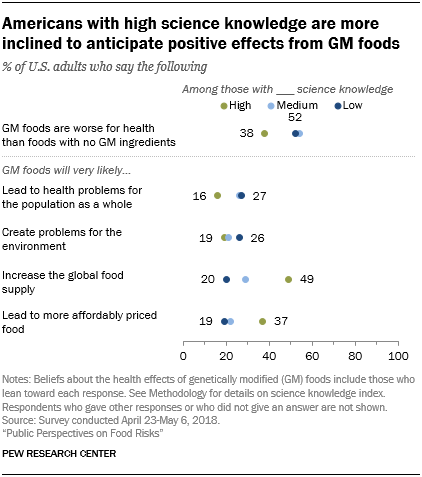

In a 2016 Pew Research Center survey, 39% of Americans said GM foods were worse for health compared with non-GM foods. The uptick in concern about GM foods in 2018 is primarily among those with low levels of science knowledge; 52% of those with low science knowledge on a nine-item index say GM foods are worse for health than non-GM foods, up 23 percentage points from 29% in 2016. But there is no shift in beliefs among those with high science knowledge; 38% in this group say GM foods are worse for health, as did 37% in 2016.

The meaning of terms such as “genetically modified” is evolving in the regulatory world. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has ruled that some uses of gene editing techniques can be indistinguishable from traditional breeding methods; those plants will not be considered genetically modified and therefore won’t be subject to regulation. The European Court of Justice took a broader approach to classification, ruling that gene-edited crops should be classified as genetically modified and, as such, subject to regulation. The Pew Research Center survey referenced only foods with “genetically modified ingredients” in order to capture common usage.

The new survey finds several patterns in people’s beliefs about food additives as well as GM foods. First, there are consistent gender differences in public views about these food issues. On average, more women than men are concerned about potential health risk from food additives and from genetically modified foods. Second, there is an inverse relationship between how much people know about science generally, based on a nine-item index of factual knowledge, and their beliefs about the health risk of foods with additives as well as GM foods. People with low science knowledge tend to express more concern about the health risk from these food groups compared with those high in science knowledge.

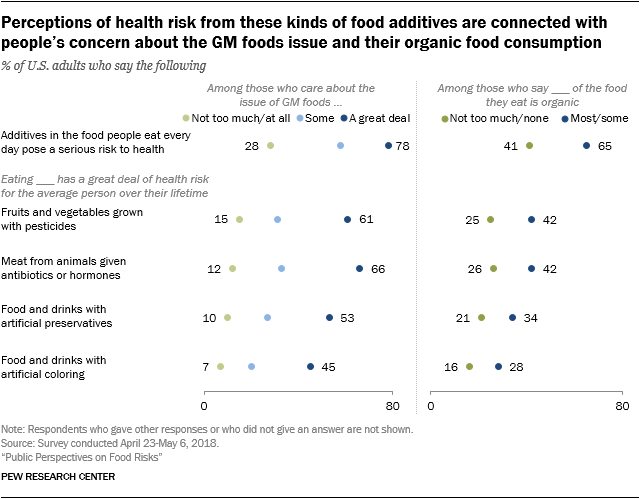

Third, public divisions over these food issues appear to reflect personal philosophies about the relationship between food and well-being. One indicator of such “food ideologies” is the amount of concern people have about the issue of GM foods. Those who care a great deal about the GM foods issue are much more likely to think GM foods are worse for one’s health, as might be expected, and they see a higher risk to health from four types of food additives: artificial coloring, artificial preservatives, pesticides used on crops and meat produced from animals given antibiotics or hormones. But while there are deep political divides over some issues connected with science – notably climate and energy issues – Democrats and Republicans hold broadly similar beliefs about potential health effects from food additives and GM foods, a finding consistent with previous Center studies on food issues.

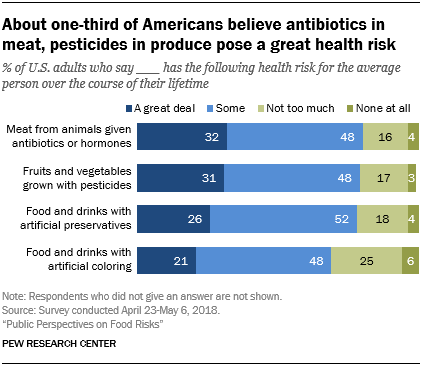

Americans hold mixed assessments of potential risk from specific types of food additives

When asked to rate the degree of long-term health risk to the average person from eating four types of foods – each with a different kind of additive introduced at some stage during food production – most Americans report at least “some” risk from meat from animals given hormones or antibiotics, or produce grown with pesticides, as well as food and beverages with artificial preservatives or coloring. Public concern is highest for meat from animals given antibiotics or hormones and produce grown with pesticides (32% and 31%, respectively, consider each to pose “a great deal” of health risk to the average person) followed by food and beverages with artificial preservatives (26%) or artificial coloring (21%).

When asked to rate the degree of long-term health risk to the average person from eating four types of foods – each with a different kind of additive introduced at some stage during food production – most Americans report at least “some” risk from meat from animals given hormones or antibiotics, or produce grown with pesticides, as well as food and beverages with artificial preservatives or coloring. Public concern is highest for meat from animals given antibiotics or hormones and produce grown with pesticides (32% and 31%, respectively, consider each to pose “a great deal” of health risk to the average person) followed by food and beverages with artificial preservatives (26%) or artificial coloring (21%).

Consumer preference for “natural” foods, a common label with no standard meaning from a U.S. regulatory perspective, raises concerns among some in the scientific community that the public has an aversion to additives and anything that might be seen as “unnatural” in the foods people eat, sometimes called chemophobia.2 The survey finds half of Americans (50%) believe at least one of these four types of foods poses a great deal of health risk over time, although only a minority of 11% believe all four do.

Still, some groups of people have more concern about what is in the food they eat. For instance, among the roughly half of Americans (51%) who believe additives, in general, pose a serious health risk overall, 71% say at least one of these four types of foods with additives poses a great deal of health risk over time, compared with 27% of those who don’t think additives pose a serious health risk who say the same. And 19% of those who believe additives pose a serious health risk overall say that all four additives pose a risk over time, compared with 2% of those who don’t think additives pose a serious health risk.

Assessments of food risk from additives vary by gender, degree of concern about the issue of GM foods and levels of science knowledge

There are consistent patterns in public beliefs about food additives. For instance, women are more likely to see a health risk in consuming foods with additives such as produce grown with pesticides. But while there are wide political differences across many social and political issues today, divides over food additives do not strongly tie to political parties (see Appendix for details).

In addition, the degree of concern people have about the issue of GM foods is a consistent indicator of their personal philosophies toward consuming additives – with those who care a great deal about GM food topics tending to be the most likely to say that additives pose a serious risk to health. Similarly, people who report eating a larger share of organic foods are more concerned about health risk from foods with additives.

Food science is complex and in flux, which creates an ongoing need for the public to stay abreast of the latest recommendations. It is perhaps fitting, then, that a person’s level of science knowledge is another factor in their views about food. Those with high science knowledge are the least concerned about potential risk from foods with additives; those with low science knowledge are more inclined to see additives overall as posing a health risk.

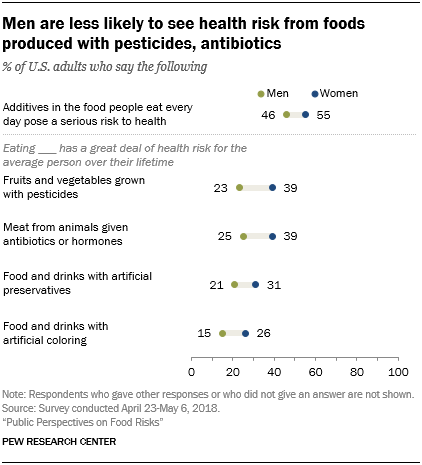

Women are more inclined than men to view food additives as a serious health risk

Women are consistently more wary than men of food additives. More women (55%) than men (46%) say that the average person is exposed to additives in the food they eat every day, which pose a serious risk to their health.

Women are also more likely to evaluate eating each of four foods with additives as having a great deal of health risk for the average person over the course of their lifetime. About four-in-ten women say fruits and vegetables grown with pesticides (39%) or meat from animals given antibiotics or hormones (39%) poses a great deal of health risk, compared with 23% and 25% of men who say the same, respectively.

And more women than men say food and drinks with artificial preservatives (31% vs. 21%) or with artificial coloring (26% vs. 15%) pose a great deal of health risk for the average person.

Americans’ beliefs about food additive risk align with their degree of concern about genetically modified foods and their organic consumption habits

There are intense debates about the health risks and benefits of foods in American society; people appear to hew to their own “food ideologies.” While these ideologies inform key attitudes and behaviors around life’s staples, such beliefs don’t align closely with political divides. (See Appendix for details.)

One marker of these divides is the extent to which people care about the issue of genetically modified foods. People who care deeply about the issue of GM foods are particularly likely to consider food additives a serious health risk and to rate produce grown with pesticides, foods with artificial preservatives or coloring or meat from animals given antibiotics or hormones as posing a great deal of threat to health. For example, roughly eight-in-ten of those who care a great deal about the issue of GM foods (78%) believe that additives pose a serious risk to people’s health, compared with 28% of those who care not too much or not at all about the issue who say the same (a 50-percentage-point difference). And 66% of those who care deeply about the issue of GM foods say meat from animals given antibiotics or hormones poses a great deal of health risk, compared with just 12% of those who do not care about the GM foods issue at all or not too much (a 54-point difference).

Demographically, those who care a great deal about the GM foods issue are diverse. Women are somewhat more likely than men to say they care a great deal about this issue (26% vs. 17%), and blacks (30%) and Hispanics (28%) are somewhat more inclined than whites (18%) to report this level of concern. But there are no more than modest differences in reported care about the issue of GM foods among other demographic, income and educational groups. (See Appendix for details.)

There are also consistent differences in beliefs about additives between those who report consuming more organics in their diet and those who don’t. Specifically, 65% of people who report that most or some of what they eat is organic say that, in general, food additives pose a serious health risk. By contrast, 41% of those who report eating a smaller share of organic food say this. Other gaps between these groups include the risk from eating produce grown with pesticides – 42% of those who report eating a larger share of organics say this poses a great deal of risk, versus 25% of those who eat a smaller share – as well as meat from animals given antibiotics or hormones (42% vs. 26%).

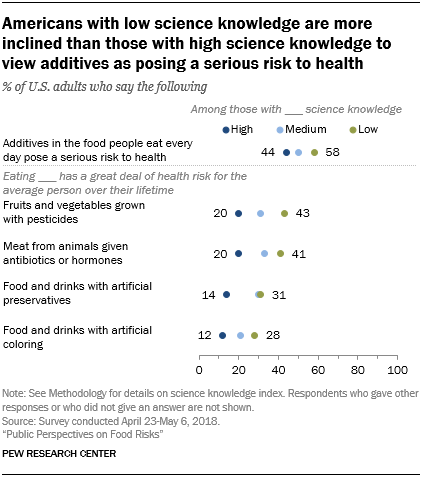

Americans’ views about the health risk of food additives tend to correspond with their levels of science knowledge

There are also differences by level of science knowledge in beliefs about the health risk posed by food additives.

The Pew Research Center survey included a set of nine questions to tap public knowledge of science across a range of principles and topics. Roughly one-in-four Americans have low (26%) or high (24%) levels of science knowledge, while 49% have a medium level of science knowledge.

The Pew Research Center survey included a set of nine questions to tap public knowledge of science across a range of principles and topics. Roughly one-in-four Americans have low (26%) or high (24%) levels of science knowledge, while 49% have a medium level of science knowledge.

The survey reveals an inverse relationship between a person’s level of science knowledge and their beliefs concerning the health risk posed by additives. For example, 43% of those with low science knowledge say eating fruits and vegetables grown with pesticides poses a great deal of health risk to the average person over their lifetime, while 20% of those with high science knowledge say the same.

Similarly, there are differences by education level in these beliefs.

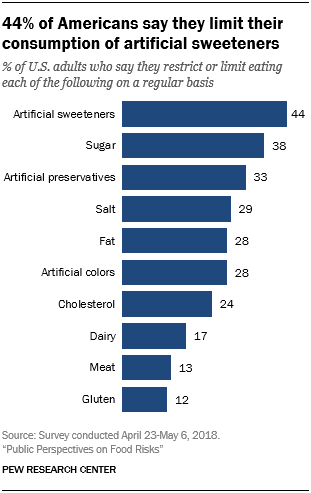

Most Americans say they watch their intake of at least one of 10 food ingredients

Public beliefs about food health risk tend to track with reported eating behaviors. The survey asked people about their eating habits regarding 10 broad types of food ingredients. Some 44% of U.S. adults say they restrict or limit consumption of artificial sweeteners. A third (33%) say they limit artificial preservatives and 28% limit foods with artificial coloring.

Public beliefs about food health risk tend to track with reported eating behaviors. The survey asked people about their eating habits regarding 10 broad types of food ingredients. Some 44% of U.S. adults say they restrict or limit consumption of artificial sweeteners. A third (33%) say they limit artificial preservatives and 28% limit foods with artificial coloring.

People who believe there is a serious risk for the average person today from food additives are more likely to report that they limit foods with artificial ingredients in their own diets. For example, 52% in this group say they restrict or limit artificial sweeteners, compared with 36% of those who believe food additives do not pose a serious risk to the average person because potentially harmful additives are consumed in such small amounts.

But artificial additives are far from the only ingredient that people restrict in their diet. About four-in-ten Americans (38%) report limiting sugar intake and about three-in-ten limit salt (29%) or fat (28%).

Roughly three-quarters of U.S. adults (76%) say they limit at least one of these 10 ingredients on a regular basis; on average, U.S. adults say they limit 2.7 items out of 10.

On average, women limit somewhat more of these ingredients than do men (2.8 items out of 10 compared with 2.5 for men). Americans ages 65 and older limit, on average, more of these food ingredients than do Americans ages 18 to 29 (3.4 vs. 2.0).

About half of U.S. adults see genetically modified foods as worse for health

The survey finds about half of Americans (49%) believe foods with GM ingredients are worse for one’s health, while 44% say such foods are neither better nor worse than non-GM foods and 5% say they are better for one’s health.

The survey finds about half of Americans (49%) believe foods with GM ingredients are worse for one’s health, while 44% say such foods are neither better nor worse than non-GM foods and 5% say they are better for one’s health.

The share of Americans who say foods with GM ingredients are worse for one’s health is up 10 percentage points, from 39% in 2016.

Still, when contemplating the effects of GM foods on society at large, Americans anticipate some positive consequences. About three-quarters (76%) of Americans say it is very (31%) or fairly likely (45%) GM foods will increase the food supply. A somewhat smaller share, though still a 63% majority, thinks it is very (25%) or fairly likely (38%) that GM foods will result in more affordably priced food.

On the other hand, majorities think GM foods are at least fairly likely to lead to health problems for the population as a whole (24% say this is very likely, 35% say it is fairly likely) or create problems for the environment (21% very likely, 35% fairly likely).

In the survey, Pew Research Center used the term “genetically modified ingredients” to reflect common usage for a genetically engineered or modified food ingredient. Such terms encompass a range of techniques, most commonly adding genetic material from another species to change, for example, a plant’s characteristics.

But what is and isn’t considered genetically modified can be murky, even among regulatory agencies. A March 2018 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) statement determined that some “genome editing” techniques are akin to traditional forms of selective breeding and therefore will not be subject to USDA regulation as a genetically modified crop, while uses that add genetic material from other “non-compatible” species such as bacteria or insects will continue to be monitored. By contrast, three months later a European court ruled that gene-edited crops should be classified as genetically modified, leading to an ongoing discussion of which technological distinctions are germane for food safety regulations.3

These distinctions may fly under the radar for many Americans. Roughly three-in-ten adults (29%) say they have heard or read a lot about GM foods, while about seven-in-ten say they heard or read a little (58%) or nothing at all (13%).

Some experts suggest that – due to limited public understanding of the term genetic modification or genetic engineering – public attitudes about genetic engineering are “soft” and more likely to fluctuate over time or in response to different question wording.4

Overall, there is a 10-percentage-point increase in the share of Americans who say that foods with GM ingredients are worse for health in the new survey compared with a 2016 Pew Research Center survey.

Further analysis shows that the shift in opinion occurs primarily among people with low science knowledge. Among this group, 52% say that GM foods are worse for health, up 23 percentage points from 29% in 2016. In contrast, there is no significant change over time in beliefs about GM foods among those with high science knowledge. This finding is consistent with the idea that those with less information about genetic engineering tend to hold “soft” attitudes, more likely to shift over time.5

Further analysis shows that the shift in opinion occurs primarily among people with low science knowledge. Among this group, 52% say that GM foods are worse for health, up 23 percentage points from 29% in 2016. In contrast, there is no significant change over time in beliefs about GM foods among those with high science knowledge. This finding is consistent with the idea that those with less information about genetic engineering tend to hold “soft” attitudes, more likely to shift over time.5

These two Center surveys, while using the same wording for beliefs about GM foods, differ in the range of other questions asked. Thus, survey context differences could also be a factor in people’s responses to the two surveys.6

Americans who think GM foods are worse for health tend to expect negative consequences for society

People who believe genetically modified (GM) foods are worse for health than foods with non-GM ingredients are more likely to have negative expectations for the effects of GM foods on public health and the environment.

People who believe genetically modified (GM) foods are worse for health than foods with non-GM ingredients are more likely to have negative expectations for the effects of GM foods on public health and the environment.

Some 40% of those who say GM foods are worse for health believe that those foods are very likely to lead to health problems for the population as a whole, compared with just 6% who say the same among those who believe GM foods are neither better nor worse for health.

Similarly, some 34% of those who believe GM foods are worse for health anticipate that GM foods will very likely create problems for the environment, while just 8% say this among those who believe GM foods are neither better nor worse.

There is a weaker relationship between one’s beliefs about GM foods and expectations that such foods will increase the global food supply. And there is no relationship between beliefs and an expectation that GM foods will lead to more affordably priced food.

Americans’ views about GM foods tend to vary by gender, degree of concern about the GM foods issue and level of science knowledge

The public’s views and expectations about the effects of GM foods adhere to some consistent patterns, similar to those observed in the survey findings about how people feel about various types of food additives.

For instance, gender again is a factor, with women more likely than men to see negative effects of GM foods. And, overall, people’s degree of concern about the GM foods issue is strongly related to their beliefs about GM foods and the potential effects of these foods on public health and the environment. There is also a relationship between science knowledge and beliefs about GM foods. Americans with a high level of science knowledge are more likely to be optimistic that GM foods will help increase the global food supply and this group is less likely to believe that GM foods are worse for one’s health than non-GM. But consistent with previous Center surveys, there are no more than modest differences in beliefs about GM foods by politics. (See Appendix for details.)

Women are more inclined than men to view GM foods as a health risk

Men and women have somewhat different expectations for GM foods. Men are more optimistic about the likely impact of GM foods on society, while women are more pessimistic.

Men and women have somewhat different expectations for GM foods. Men are more optimistic about the likely impact of GM foods on society, while women are more pessimistic.

Some 56% of women compared with 43% of men believe that GM foods are worse for health than foods without GM ingredients. And women are more inclined than men to expect problems ahead from GM foods for public health (30% vs. 17%) or the environment (27% vs. 16%).

Conversely, men, more than women, think it very likely that GM foods will increase the global food supply (37% vs. 26%) or lead to more affordably priced food (28% vs. 22%).

Personal concern about the issue of GM foods is closely tied with beliefs about the effects of GM foods

Overall, a minority of about one-in-five Americans (22%) say they care a great deal about the issue of GM foods, while an additional roughly four-in-ten (39%) say they care some. About four-in-ten say they care either not too much (28%) or not at all (10%) about this issue.

Overall, a minority of about one-in-five Americans (22%) say they care a great deal about the issue of GM foods, while an additional roughly four-in-ten (39%) say they care some. About four-in-ten say they care either not too much (28%) or not at all (10%) about this issue.

But the 22% of the public that cares deeply about the issue of GM foods holds views that are distinct from those of other Americans.

For instance, a large majority of Americans who care a great deal about the GM foods issue (80%) say foods with GM ingredients are worse for their health than foods with no GM ingredients. In contrast, among those who care not too much or not at all about the issue of GM foods, two-in-ten (20%) say foods with GM ingredients are worse for their health, while most of this group (73%) says GM foods are neither better nor worse than foods with no GM ingredients.

Similarly, people who care deeply about the issue of GM foods are also more likely to think that negative health and environmental effects will accrue as a result of GM foods. A majority of those who care a great deal about the issue of GM foods (63%) say GM foods will very likely lead to health problems for the population as a whole, compared with just 7% of those who care not too much or not at all about the issue who say the same. At the same time, those who care a great deal are more likely than other Americans to think GM foods will increase the food supply and lead to affordably priced foods, although no more than half of any of these groups consider this very likely.

About half of those with high science knowledge expect GM foods to increase the food supply

At a time when biotechnology continues to push the boundaries of crop development, the survey finds a relationship between how much people know about science and their beliefs about GM foods. People with high science knowledge, based on a nine-item index, are the most positive in their assessments of GM foods, while those with less understanding of science register more concern about GM foods.

For instance, people with high science knowledge are less inclined than those with less science knowledge to believe that GM foods are worse for one’s health than foods with no GM ingredients (38% of those with high science knowledge say this, vs. 54% of those with medium and 52% of those with low science knowledge).

For instance, people with high science knowledge are less inclined than those with less science knowledge to believe that GM foods are worse for one’s health than foods with no GM ingredients (38% of those with high science knowledge say this, vs. 54% of those with medium and 52% of those with low science knowledge).

At the same time, about half (49%) of those with high science knowledge say it is very likely that GM foods will increase the global food supply and 37% in this group say it is very likely that GM foods will lead to affordably priced foods. By comparison, about one-in-five of those with low science knowledge say each of these is very likely to happen (20% for increasing the global food supply and 19% for leading to more affordably priced food).

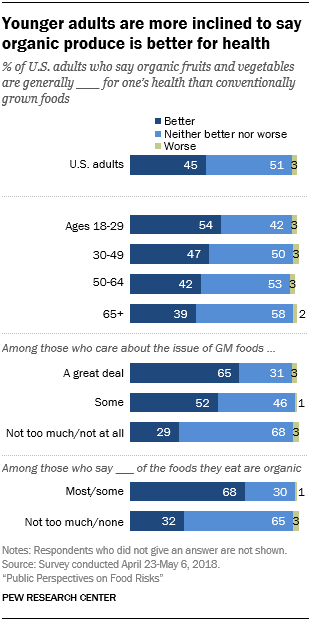

45% of Americans believe organic produce provides net benefits for health; 51% see no health advantage for organics over conventionally grown options

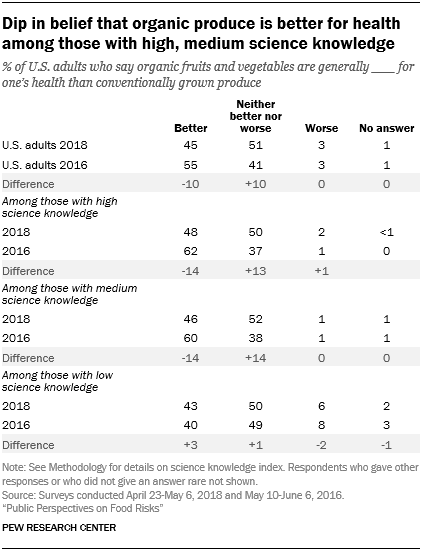

Americans are closely divided over whether organic fruits and vegetables are better for one’s health than conventionally grown foods: 45% say they are, while 51% say that organic produce is neither better nor worse for health than conventionally grown produce.

Americans are closely divided over whether organic fruits and vegetables are better for one’s health than conventionally grown foods: 45% say they are, while 51% say that organic produce is neither better nor worse for health than conventionally grown produce.

Younger Americans are more likely than their older counterparts to believe that organics are better for one’s health than conventionally grown produce. Some 54% of those ages 18 to 29 and 47% of those 30 to 49 say organic foods are better for one’s health. By comparison, 39% of those ages 65 and older believe organic foods are better for one’s health than conventionally grown foods.

People who care deeply about the issue of GM foods are more than twice as likely as those with less concern about this issue to say organic foods are better for one’s health than conventionally grown foods (65% of those who care a great deal about the issue of GM foods say this vs. 29% of those who care not too much or not at all).

About four-in-ten Americans (39%) estimate that most (7%) or some (32%) of what they eat is organic. A majority of this group (68%) believes that organic produce is better for one’s health than conventionally grown options. By comparison, 32% of those who report eating no or not too much organic food believe that organic produce is better for one’s health.

While women are more inclined than men to see health risk from GM foods and food additives, there are no differences between men and women when it comes to beliefs about the comparative health benefits of organic produce. Similarly, there were no significant differences between men and women on beliefs about the health effects of organic produce in the Center’s 2016 survey.

The share of U.S. adults who say organic produce is better for one’s health declined from 55% in 2016 to 45% this year. While people of all levels of science knowledge are about equally likely in the new survey to say organic produce is better for health, the shifts from 2016 in beliefs about organic produce occurred among those with high and medium science knowledge. People with low science knowledge held similar beliefs in both years.