As their numbers rise, Asian Americans are contributing to the diversity of the U.S. religious landscape. From less than 1% of the total U.S. population (including children) in 1965, Asian Americans have increased to 5.8% (or 18.2 million children and adults in 2011, according to the U.S. Census).3 In the process, they have been largely responsible for the growth of non-Abrahamic faiths in the United States, particularly Buddhism and Hinduism. Counted together, Buddhists and Hindus today account for about the same share of the U.S. public as Jews (roughly 2%). At the same time, most Asian Americans belong to the country’s two largest religious groups: Christians and people who say they have no particular religious affiliation.

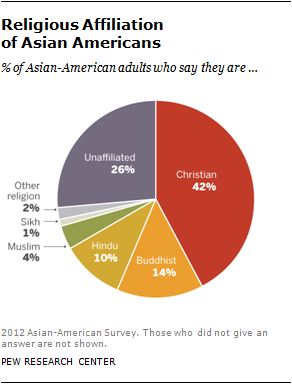

According to a comprehensive, nationwide survey of Asian Americans conducted by the Pew Research Center, Christians are the largest religious group among U.S. Asian adults (42%), and the unaffiliated are second (26%). Buddhists are third, accounting for about one-in-seven Asian Americans (14%), followed by Hindus (10%), Muslims (4%) and Sikhs (1%). Followers of other religions make up 2% of U.S. Asians.

Not only do Asian Americans, as a whole, present a mosaic of many faiths, but each of the six largest subgroups of this largely immigrant population also displays a different religious complexion. A majority of Filipinos in the U.S. are Catholic, while a majority of Korean Americans are Protestant. About half of Indian Americans are Hindu, while about half of Chinese Americans are unaffiliated. A plurality of Vietnamese Americans are Buddhist, while Japanese Americans are a mix of Christians, Buddhists and the unaffiliated.

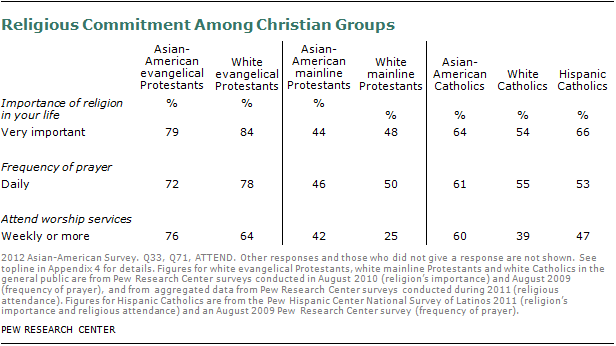

Indeed, when it comes to religion, the Asian-American community is a study in contrasts, encompassing groups that run the gamut from highly religious to highly secular. For example, Asian Americans who are unaffiliated tend to express even lower levels of religious commitment than unaffiliated Americans in the general public; 76% say religion is not too important or not at all important in their lives, compared with 58% among unaffiliated U.S. adults as a whole. By contrast, Asian-American evangelical Protestants rank among the most religious groups in the U.S., surpassing white evangelicals in weekly church attendance (76% vs. 64%). The overall findings, therefore, mask wide variations within the very diverse Asian-American population.

Asian Americans as a whole are less likely than Americans overall to believe in God and to pray on a daily basis, and a somewhat higher proportion of Asian Americans are unaffiliated with any religion (26%, compared with 19% of the general public). But some of these measures (such as belief in God and frequency of prayer) may not be very good indicators of religion’s role in a mostly non-Christian population that includes Buddhists and others from non-theistic traditions. Most Asian-American Buddhists and Hindus, for instance, maintain traditional religious beliefs and practices. Two-thirds of Buddhists surveyed believe in ancestral spirits (67%), while three-quarters of Hindus keep a shrine in their home (78%) and 95% of all Indian-American Hindus say they celebrate Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights.

At the same time, the Pew Research Center survey also finds evidence that Asian-American Buddhists and Hindus are adapting to the U.S. religious landscape in ways large and small:

- Roughly three-quarters of both Asian-American Buddhists (76%) and Asian-American Hindus (73%) celebrate Christmas.

- Three-in-ten (30%) of the Hindus and 21% of the Buddhists surveyed say they sometimes attend services of different religions (not counting special events such as weddings and funerals).

- About half (54%) of Asian Americans who were raised Buddhist remain Buddhist today, with substantial numbers having converted to Christianity (17%) or having become unaffiliated with any particular faith (27%).

How can many Asian-American Buddhists and Hindus maintain their traditional beliefs and practices while at the same time adopting aspects of America’s predominantly Christian religious culture, such as celebrating Christmas? Part of the answer may be that U.S. Buddhists and Hindus tend to be inclusive in their understanding of faith. Most Asian-American Buddhists (79%) and Asian-American Hindus (91%), for instance, reject the notion that their religion is the one, true faith and say instead that many religions can lead to eternal life (or, in the case of Buddhists, to enlightenment). In addition, the vast majority of Buddhists (75%) and Hindus (90%) in the survey say there is more than one true way to interpret the teachings of their religion.

By contrast, Asian-American Christians—particularly evangelical Protestants—are strongly inclined to believe their religion is the one, true faith leading to eternal life. Indeed, Asian-American evangelicals are even more likely than white evangelical Protestants in the U.S. to take this position. Nearly three-quarters of Asian-American evangelicals (72%) say their religion is the one, true faith leading to eternal life, while white evangelical Protestants are about evenly split, with 49% saying their religion is the one, true faith leading to eternal life and 47% saying many religions can lead to eternal life.

These are among the key findings of the new survey by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life and Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends project. The Pew Research Center’s 2012 Asian-American Survey is based on telephone interviews conducted by landline and cell phone with a nationally representative sample of 3,511 Asian adults ages 18 and older living in the United States. The survey was conducted in all 50 states, including Alaska and Hawaii, and the District of Columbia. (For more details, see “About the Survey” and Appendix 3: Survey Methodology.)

Religious Affiliation

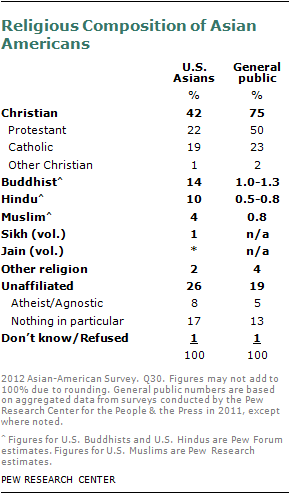

The survey finds a plurality of Asian Americans are Christian (42%), including 22% who are Protestant and a slightly smaller percentage who are Catholic (19%). About a quarter (26%) are unaffiliated (atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular). Roughly one-in-seven Asian Americans are Buddhist (14%) and one-in-ten are Hindu (10%). The remainder consists of Muslims, Sikhs, Jains and followers of numerous other faiths.4

Thus, Asian Americans are more religiously diverse than the U.S. population, which is overwhelmingly Christian (75%). There are also substantial differences in religious affiliation among the largest subgroups of Asian Americans by country of origin.

As the pie charts below show, about half of Chinese Americans—the single largest subgroup, making up nearly a quarter of the total U.S. Asian population—are unaffiliated (52%). (Also see the “Religious Affiliation Among U.S. Asian Groups” table in Chapter 1: “Religious Affiliation.”) Filipinos—the second-largest subgroup, accounting for about one-in-five U.S. Asian children and adults—are mostly Catholic (65%). Indian Americans represent about 18% of all U.S. Asians, and about half identify as Hindu (51%); 59% say they were raised Hindu. Vietnamese Americans, who comprise 10% of U.S. Asians, include a plurality of Buddhists (43%). U.S. Koreans (also about 10% of all Asian Americans) are mostly Protestant (61%). Japanese Americans—the smallest of the six subgroups, representing about 7.5% of the U.S. Asian population—are more mixed: more than one-third are Christian (38%, including 33% who are Protestant), another third are unaffiliated (32%) and a quarter are Buddhist (25%).5

These proportions generally reflect the religious composition of each group’s country of origin. The Philippines, for example, is heavily Catholic. In some cases, however, the percentage of Christians among Asian-American subgroups is much higher than in their ancestral lands. For example, 31% of the Chinese Americans surveyed are Christian; the vast majority, though not all, of this group come from mainland China, where Christians generally are estimated to constitute about 5% of the total population.6 Similarly, 18% of Indian Americans identify as Christian, though only about 3% of India’s total population is estimated to be Christian.7 The higher percentages of Christians are a result of the disproportionate number of Christians who choose to migrate to the United States and may also reflect religious switching by immigrants.8 (For more details on religious switching, see “Religious Switching and Intermarriage” and Chapter 2, “Religious Switching and Intermarriage.”)

Religious Commitment

By several conventional measures, religion appears to be less important to Asian Americans than to the U.S. public as a whole. For example, fewer Asian Americans say religion is very important in their lives (39% of U.S. Asians vs. 58% of all U.S. adults), while more say religion is either not too important or not at all important to them (30% of U.S. Asians vs. 16% of the general public). In addition, the proportion of Asian Americans who are unaffiliated (26%) is higher than in the general public (19%). Asian Americans are also less likely to say they pray on a daily basis, and they report attending religious services at somewhat lower rates than the general public. (For more details, see Chapter 3, “Importance of Religion.”)

These relatively lower levels of religious engagement are not simply an effect of age or education.9 Analysis of the data shows that Asian Americans tend to be less religious on these measures than the general public even when controlling for age and level of educational attainment. For example, 29% of Asian Americans with some post-graduate education say that religion is very important in their lives, compared with 52% of all Americans who have studied at the post-graduate level.

The overall results for Asian Americans, however, mask big differences among Asian-American religious groups. Asian-American Buddhists and Asian-American Hindus, for example, are much less inclined than Asian-American Christians to say that religion plays a very important role in their lives.

Moreover, these figures underscore major differences in religious beliefs and practices between Christianity and other religions. Because Buddhists often view their religion in non-theistic terms—simply put, many see Buddhism as a path toward spiritual awakening or enlightenment rather than as a path to God—it is not surprising that the proportion of Asian-American Buddhists who say they believe in God or a universal spirit is lower (71%) than among Asian Americans who are not Buddhist (80%) and among the U.S. public overall (92%). Similarly, Buddhists and Hindus may regard prayer differently than Christians do. The ritual recitation of mantras (in both Buddhism and Hinduism) is not the same as prayer to a personal God in the Christian tradition, and this difference may help explain why a smaller number of Asian-American Buddhists and Hindus than Asian-American Christians report that they pray daily. And although attendance at religious services is higher among U.S. Asian Christians than among U.S. Asian Buddhists and Hindus, many of the Buddhists and Hindus report that they maintain religious shrines in their homes.

Asian-American Christians

On one common indicator of religious commitment, Asian-American Christians are slightly lower than U.S. Christians as a whole: 64% of Asian-American Christians say religion is very important in their lives, compared with 70% of Christians in the general public. But on some measures, Asian-American Christians are more committed than U.S. Christians as a whole. For example, six-in-ten Asian-American Christians say they attend services at least once a week (61%), compared with 45% of all U.S. Christians.

Asian-American Christians are also more inclined than U.S. Christians as a whole to say that living a very religious life is one of their most important goals (37% vs. 24%).

Among Asian-American Christians, the highest self-reported attendance rates are among evangelical Protestants, 76% of whom go to services at least once a week, followed by Catholics (60% at least once a week) and mainline Protestants (42%). All three Asian-American Christian groups attend services more frequently than do their counterparts in the general public.

On the other hand, Asian-American evangelicals are similar to white evangelical Protestants in the general public on some measures of religious commitment: Both groups are about equally likely to consider religion very important in their lives, and both groups are about equally likely to pray daily.

The same pattern holds among mainline Protestants. Asian-American mainline Protestants attend worship services more often (42% attend at least once a week) than do white mainline Protestants in the general public (25% attend at least once a week). The two groups are similar, however, when it comes to frequency of prayer and importance of religion in their lives.

Compared with white, non-Hispanic Catholics in the U.S., Asian-American Catholics exhibit higher levels of religious commitment on several measures. Roughly two-thirds of Asian-American Catholics (64%) say religion is very important in their lives, compared with 54% of white Catholics. Six-in-ten Asian-American Catholics say they attend worship services at least once a week, compared with about four-in-ten white Catholics (39%). Asian-American Catholics are also a bit more likely than white Catholics to pray daily (61% vs. 55%).

Asian-American Evangelicals

Asian-American evangelicals are more inclined than white evangelicals to say their religion is the one, true faith leading to eternal life (72% of Asian-American evangelicals vs. 49% of white evangelicals) and to believe that there is only one true way to interpret the teachings of their religion (53% vs. 43%). Asian-American evangelicals are just as likely as white evangelicals to say the Bible is the word of God, though Asian Americans are somewhat less inclined to say everything in Scripture should be taken literally, word for word.

About one-third of Asian-American evangelical Protestants are of Korean descent (34%). On most measures of religious commitment, Korean-American evangelicals look similar to Asian-American evangelicals from other countries of origin. In one regard, however, Korean evangelicals stand out from other Asian evangelicals: Korean evangelical Protestants are particularly likely to hold a literal view of the Bible; 68% express this view. By comparison, 44% of Asian-American evangelicals who are not Korean say the Bible should be interpreted literally.

Asian-American Buddhists

As noted above, Asian-American Buddhists are less inclined than Asian-American Christians to say religion is very important in their lives. But many nevertheless maintain distinctive religious beliefs and practices. Roughly two-thirds say they believe in ancestral spirits (67%) and reincarnation (64%). Nearly as many believe that spiritual energy can be located in physical things such as mountains, trees or crystals (58%) and see yoga—a practice more commonly associated with Hinduism—not just as exercise but as a spiritual practice (58%). About half believe in nirvana (51%), defined in the survey as “the ultimate state transcending pain and desire in which individual consciousness ends.” And although just 12% say they attend religious services at least once a week, 57% of Asian-American Buddhists say they have a shrine in their home.

On the other hand, meditation—a practice with deep roots in some, but not all, forms of Buddhism—seems to be relatively uncommon among Asian-American Buddhists. A solid majority says they seldom or never meditate (60%), and just one-in-seven engages in meditation on a daily basis (14%), a lower rate than among Asian-American Christians (27%) and Hindus (24%). It is possible, of course, that what Christians have in mind when they say they engage in meditation is different from what Buddhists mean by that term.

Buddhists of Vietnamese descent make up more than a third of all Asian-American Buddhists (38%); they stand out from other Asian-American Buddhists for their relatively high levels of religious commitment and practice. Vietnamese-American Buddhists are more likely than other Asian-American Buddhists to say religion is very important in their lives. Eight-in-ten have a shrine in their home, compared with 43% of other Asian-American Buddhists. About half of Vietnamese-American Buddhists fast during holy times (51%); just 10% of other Asian-American Buddhists do this. Vietnamese-American Buddhists are also somewhat more likely than other Asian-American Buddhists to pray at least once a day, to attend worship services at least occasionally and to attend services of different religious faiths. However, they are about as likely as other Asian-American Buddhists to engage in daily meditation (11% vs. 16% for other Asian-American Buddhists).

Asian-American Hindus

Asian-American Hindus also maintain some distinctive religious beliefs and practices. Yoga has a long tradition in Hinduism, and nearly three-quarters of U.S. Asian Hindus see it not just as exercise but as a spiritual practice (73%). More than half of Asian-American Hindus say they believe in reincarnation and moksha, defined in the survey as “the ultimate state transcending pain and desire in which individual consciousness ends” (59% each). About half also believe in astrology (53%), defined in the survey as the belief “that the position of the stars and planets can affect people’s lives.” Fewer believe in spiritual energy in physical things (46%) or in ancestral spirits (34%).

In addition, Hindus tend to practice their religion in different ways than do Christians. Although just 19% of Asian-American Hindus say they attend worship services at least once a week, nearly eight-in-ten (78%) have a shrine in their home. The celebration of Diwali, the Hindu festival of lights, is nearly universal among Indian-American Hindus (95%).

Overall, Asian-American Hindus say they pray less often than do members of the general public. About half of U.S. Hindus surveyed (48%) report praying every day. Among U.S. adults in the general public 56% report praying daily.

Nearly all Asian-American Hindus surveyed trace their heritage to India (93%). But the percentage of Asian-American Hindus who say that religion is very important in their lives (32%) is considerably lower than the percentage of Hindus in India who say this (69%, according to a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project).

Unaffiliated Asian Americans

About a quarter of U.S. Asians (26%) are religiously unaffiliated—meaning that they say they are atheist, agnostic or have no particular religion—which is somewhat higher than the share of unaffiliated in the general public (19%). It is important to realize, however, that “unaffiliated” does not necessarily mean “non-religious.” Many people who are unaffiliated with any particular religion nonetheless express religious beliefs (such as belief in God or reincarnation) and engage in religious practices (such as prayer or meditation).

But Asian Americans who are unaffiliated tend to report lower levels of interest in religion than unaffiliated Americans as a whole. For example, four-in-ten unaffiliated U.S. adults say religion is either somewhat important (26%) or very important (14%) in their lives. By comparison, less than a quarter of unaffiliated U.S. Asians say religion is either somewhat (18%) or very (4%) important to them. Unaffiliated U.S. Asians also are less likely than unaffiliated people in the general public to believe in God (49% vs. 67%) or to pray at least once a day (6% vs. 22%).

Asian Americans with no religious affiliation, like unaffiliated Americans as a whole, infrequently attend worship services and tend to believe the Bible is a human artifact rather than the word of God. Unaffiliated Asian Americans are more inclined than those in the general public to believe in yoga as a spiritual practice (42% vs. 28%). But they are no more likely to believe in reincarnation, astrology or the presence of spiritual energy in physical things such as mountains, trees or crystals.

Overall, the proportion of native-born U.S. Asians who are religiously unaffiliated (31%) is somewhat higher than among foreign-born Asian Americans (24%). Fully half of Chinese Americans (52%)—including 55% of those born in the U.S. and 51% of those born overseas—describe themselves as religiously unaffiliated. Because Chinese Americans are the largest subgroup of U.S. Asians, nearly half of all religiously unaffiliated Asians in the U.S. are of Chinese descent (49%). While some Chinese Americans come from Taiwan, Hong Kong and elsewhere, they come primarily from mainland China, which has very high government restrictions on religion and where much of the population is religiously unaffiliated.10 Fully eight-in-ten Chinese (80%) say they have no religion, according to the 2012 Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes survey in China (for details, see Appendix 2).

Though not nearly as high as among Chinese Americans, the percentage of Japanese Americans who say they are religiously unaffiliated (32%) is also higher than among the general public (19%). But among other Asian-American groups, the percentage that is unaffiliated either is closer to the general public (Korean Americans at 23%, Vietnamese Americans at 20%) or falls below the number for Americans as a whole (Indian Americans at 10%, Filipino Americans at 8%).

Religious Switching and Intermarriage

One-third of Asian adults in the U.S. no longer belong to the religious group in which they were raised (32%). By comparison, the Pew Forum’s 2007 “U.S. Religious Landscape Survey” found that 28% of adults in the U.S. have switched religions.11 (In this analysis, Protestants raised in a denomination different from their current denomination, such as those raised as Methodist and now Presbyterian, are not counted as “switching.”) Conversion rates are higher among Japanese, Chinese and Korean Americans than among other U.S. Asian groups.

There have been substantial gains due to religious switching among Asian Americans who say they are not affiliated with any particular religion. Not quite one-in-five Asian Americans (18%) say they were raised with no affiliation as children, while 26% are unaffiliated today, a net gain of eight percentage points. A similar pattern prevails in the U.S. general public, where the share of the population that is unaffiliated also has grown through religious switching.12

Asian-American Protestants also have seen net growth through switching: 22% of Asian Americans identify as Protestant today, compared with 17% who say they were raised Protestant.

Asian-American Catholics (with a net loss of three percentage points) and Hindus (with a net loss of two percentage points) have stayed roughly the same size, with little net impact from switching.

Asian-American Buddhists have experienced the biggest net losses from religious switching. Roughly one-in-five Asian Americans (22%) say they were raised as Buddhist, and 2% have switched to Buddhism from other faiths (or from having no particular religion). But 10% of Asian Americans have left Buddhism, for a net loss of eight percentage points.

Of all the largest Asian-American religious groups, Hindus have the highest retention rate. Fully 81% of Asian Americans who were raised Hindu remain Hindu today; 12% have become unaffiliated, and the rest have switched to other faiths (or did not give a current religion).

Religious switching is more common among native-born Asian Americans than among foreign-born Asian Americans. Among those born in the U.S., 40% have a religion different from the one in which they were raised. Among foreign-born Asian Americans, this figure is 30%.

Three-quarters of married Asian Americans (76%) have a spouse of the same religion, and 23% are married to someone of a different faith.13 By comparison, the Pew Forum’s 2007 “U.S. Religious Landscape Survey” found that roughly one-quarter of married people in the general public have a spouse with a different faith.14

By far the lowest intermarriage rate is among Hindus. Nine-in-ten married Hindus (94%) have a spouse who is also Hindu. About eight-in-ten Asian-American Catholics (81%) and Protestants (also 81%) are married to fellow Catholics or Protestants, respectively. Seven-in-ten Buddhists are married to fellow Buddhists (70%) and 61% of those with no religious affiliation have a spouse who is also unaffiliated.

For more details see Chapter 2, “Religious Switching and Intermarriage.”

Social and Political Attitudes

The social and political attitudes of U.S. Asians vary by religious group. Asian-American evangelical Protestants (like white evangelicals) overwhelmingly hold conservative views on homosexuality and abortion. Unaffiliated Asian Americans (like the unaffiliated in the general public) overwhelmingly take liberal positions on these social issues. The other Asian-American religious groups tend to fall somewhere in between. (For more details, see Chapter 6, “Social and Political Attitudes.”)

Among all Asian Americans, 53% say homosexuality should be accepted by society, and 35% say homosexuality should be discouraged by society. (By comparison, among the general public, 58% say homosexuality should be accepted, while 33% say it should be discouraged by society.) Unaffiliated U.S. Asians lean most strongly toward acceptance of homosexuality (69%). Smaller majorities or pluralities of Asian-American Catholics (58%), Buddhists (54%), Hindus (54%) and mainline Protestants (49%) agree. Among Asian-American evangelicals, however, the preponderance of opinion is reversed: 65% say homosexuality should be discouraged, and 24% say it should be accepted by society.

Similarly, Asian Americans as a whole tend to support abortion rights: 54% say it should be legal in all or most cases; 37% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Support for legal abortion is highest among U.S. Asians who are religiously unaffiliated (74%), followed by Hindus (64%), Buddhists (59%) and mainline Protestants (50%). But the majority of Asian-American Catholics (56%) and evangelical Protestants (64%) say abortion should be illegal in most or all cases. Among the general public, by comparison, 51% say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 43% say it should be illegal.

When it comes to political party identification, more Asian-American voters identify with or lean to the Democratic Party than the Republican Party. Among all Asian-American registered voters (which excludes non-citizens in this largely immigrant population), the Democratic Party holds a 20-percentage-point advantage (52% to 32%), a much wider margin than in the general public (49% to 45%).

Seven-in-ten Asian-American Hindu voters (72%) either consider themselves a Democrat or say they lean Democratic, as do 63% of unaffiliated U.S. Asians. Asian-American Buddhist voters also tilt strongly Democratic (56% vs. 27% Republican/lean Republican). Asian-American mainline Protestant and Catholic registered voters, like mainline Protestants and Catholics in the general public, are more evenly split. And evangelical Asian Americans lean strongly toward the GOP (56% vs. 28% Democratic/lean Democratic), though not as strongly as do white evangelical Protestant registered voters (66% Republican/lean Republican vs. 24% Democratic/lean Democratic).

In terms of political ideology, Asian Americans also tend to be more liberal than the general public. Among all U.S. Asians, 31% describe their political views as liberal and 24% as conservative. In the U.S. public, the balance is reversed: 24% say they are liberal, 34% conservative.

Among Asian-American religious groups, the unaffiliated, Hindus and Buddhists tilt to the liberal side, while Asian-American evangelicals tilt conservative (16% liberal vs. 45% conservative), though they are not as conservative as white evangelical Protestants (7% liberal vs. 61% conservative). Again, Asian-American mainline Protestants and Catholics are more evenly split, and their ideological leanings look very similar to those of white mainline Protestants and U.S. Catholics overall.

Not surprisingly, given these patterns in partisanship and ideology, Asian Americans strongly supported Democrat Barack Obama over Republican John McCain in the 2008 election. Of those who say they went to the polls, 63% report that they voted for Obama, 26% for McCain. All the Asian-American religious groups favored Obama with the exception of evangelical Protestants, who supported McCain by a 10-point margin (45% McCain vs. 35% Obama). The highest margins of voting for Obama were among Hindus (85% Obama vs. 7% McCain) and unaffiliated U.S. Asians (72% Obama vs. 18% McCain).

While Asian-American Hindus are much more likely to identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party than the Republican Party and voted overwhelmingly for Obama, their views on the size of government are more mixed. Asked whether they would prefer to have a smaller government providing fewer services or a bigger government providing more services, 46% of Asian-American Hindus say they would prefer a bigger government, while 41% say they would prefer a smaller one.

On the question of whether they think of themselves as “a typical American or very different from a typical American,” U.S. Asians overall are more likely to see themselves as very different (53%) rather than as typical (39%).

Views on this question are strongly linked to whether an individual was born in the U.S. or outside of the U.S.; foreign-born Asian Americans are more likely than those born in the United States to see themselves as “very different” (60% vs. 31% for U.S. born). In addition, religious affiliation is also associated with attitudes on this question. Asian Americans who are Christian are more likely to see themselves as typical Americans than either Buddhists or Hindus, even when place of birth and length of time living in the U.S. are held constant.

Socioeconomic Characteristics of Religious Groups

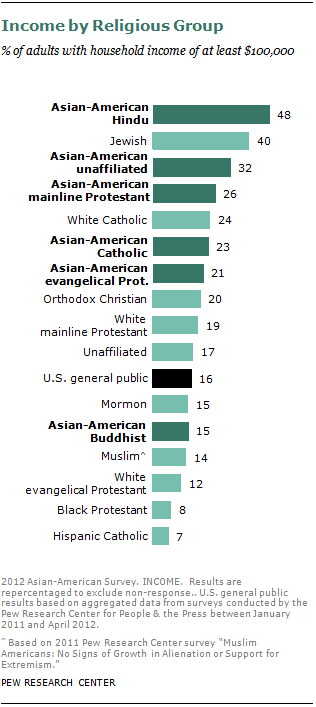

In terms of education and income, Hindus are at the top of the socioeconomic ladder—not only among Asian-American religious groups but also among all the largest U.S. religious groups. Fully 85% of Asian-American Hindu adults are college graduates, and more than half (57%) have some post-graduate education. That is nearly five times the percentage of adults in the general public who have studied at the post-graduate level (12%) and 23 percentage points higher than U.S. Jews, the second-ranking religious group in terms of post-graduate education.

As the chart above shows, all the largest Asian-American religious groups are above the U.S. average in post-graduate education. The differences among Asian Americans, nevertheless, are striking. The share of Asian-American Hindus who have studied at the post-graduate level is 40 percentage points higher than among Asian-American Buddhists and Catholics. This reflects the great diversity of origins and circumstances among U.S. Asians, including some who have come to the United States as refugees or unskilled workers and others who have come to pursue a higher education or opportunities in the high-tech industry, science, engineering and medicine.

The high socioeconomic status of Asian Americans in general, and of Hindus in particular, is due at least in part to selective immigration. Many Asian immigrants come to the U.S. through the H-1B visa program, which is designed to encourage immigration of engineers, scientists and other highly skilled “guest workers” from abroad. In 2011, for example, India accounted for more than half of all the H-1B visas granted. The vast majority of U.S. Hindus are of Indian descent, and Indian Americans as a whole are a well-educated, affluent group. But Indian-American Hindus tend to have even more years of education and higher household incomes than other (non-Hindu) Indian Americans: 51% of Hindu Indian-American adults live in households earning at least $100,000 annually, compared with 34% of non-Hindu Indian Americans, and 58% of Hindu Indian Americans have studied at the post-graduate level, compared with 36% of non-Hindu Indian Americans. To some extent, this may reflect the relatively high socioeconomic status of Hindus in India.15

Asian-American Buddhists are a much different population. Many belong to a wave of immigrants who came to the United States as refugees from Vietnam and other Southeast Asian countries.16

As a consequence, their educational attainment levels and household incomes tend to be lower; 34% hold a bachelor’s degree, and 27% report household earnings of at least $75,000—including 15% with incomes of at least $100,000 (see the full demographic table). More than a third of Asian-American Buddhists (37%) report household incomes of less than $30,000 annually, compared with 12% among Asian-American Hindus. Only 36% of Asian-American Buddhists rate their personal financial situation as good or excellent, about half the share of Asian-American Hindus who do so (70%).

It should be noted, however, that Buddhists in the United States also include many native-born, non-Asian converts who tend to have relatively high education and income levels.17 By the Pew Forum’s estimate, about two-thirds (67%–69%) of all U.S. Buddhists are Asian American—the group covered by this survey. Thus, the survey presents a portrait of Asian-American Buddhists, not of U.S. Buddhists as a whole.

The Pew Forum estimates that Buddhists make up between 1.0% and 1.3% of the adult population in the U.S., and that 67% to 69% of all U.S. Buddhists are Asian Americans. Hindus make up between 0.5% and 0.8% of the U.S. adult population, and between 85% and 97% of all U.S. Hindus are Asian American, according to the Pew Forum’s estimates.19

Asian-American Christians generally fall between Buddhists and Hindus in terms of educational attainment and measures of financial well-being. About half of the Christians surveyed are college graduates (49%) and about a third report household incomes of at least $75,000 (37%). There is little difference in the socioeconomic status of Asian-American Catholics and Protestants. But the Protestant category can be further broken down into evangelical (about 13% of Asian Americans) and mainline (9%).18 Asian-American mainline Protestants are more likely than Asian-American evangelicals to rate their personal finances as good or excellent (57% vs. 42%), although differences in household incomes between these two groups are not statistically significant.

Religiously unaffiliated Asian Americans tend to have relatively high levels of education (58% are college graduates) and household income (43% at least $75,000), though not as high as Hindu Asian Americans.

About the Survey

The Pew Research Center’s 2012 Asian-American Survey is based on telephone interviews conducted by landline and cell phone with a nationally representative sample of 3,511 Asian adults ages 18 and older living in the United States. The survey was conducted in all 50 states, including Alaska and Hawaii, and the District of Columbia. The survey was designed to include representative subsamples of the six largest Asian groups in the U.S. population: Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese. Americans who trace their origins to many other Asian countries—including Bangladeshis, Burmese, Cambodians, Hmong, Laotians, Pakistanis, Thais and numerous smaller U.S. Asian groups—also are represented in the survey. However, the sample does not contain enough individuals from every country of origin to analyze all subgroups separately.

Respondents who identified as “Asian or Asian American, such as Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese” were eligible to complete the survey interview, including those who identified with more than one race and regardless of Hispanic ethnicity. The question on racial identity also offered the following categories: white, black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.

Classification into U.S. Asian groups is based on self-identification of respondent’s “specific Asian group.” Asian groups named in this open-ended question were “Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, or of some other Asian background.” Respondents self-identified with more than 22 specific Asian groups. Those who identified with more than one Asian group were classified based on the group with which “they identify most.” Respondents who identified their specific Asian group as Taiwanese or Chinese Taipei are classified as Chinese Americans for this report.

The survey was conducted using a probability sample from multiple sources. The data are weighted to produce a final sample that is representative of Asian adults in the United States. Survey interviews were conducted under the direction of Abt SRBI, in English and Cantonese, Hindi, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Tagalog and Vietnamese. For more details on the methodology, see Appendix 3.

- The survey was conducted Jan. 3-March 27, 2012, in all 50 states, including Alaska and Hawaii, and the District of Columbia.

- The survey included 3,511 interviews, including 728 interviews with Chinese Americans, 504 interviews with Filipino Americans, 580 interviews with Indian Americans, 515 interviews with Japanese Americans, 504 interviews with Korean Americans, 504 interviews with Vietnamese Americans and 176 interviews with Asians of other backgrounds.

- Margin of error is plus or minus 2.4 percentage points for results based on the total sample at the 95% confidence level. Margins of error for results based on subgroups of Asian Americans, ranging from 3.1 to 7.8 percentage points, are included in Appendix 3.

Notes on Terminology

Unless otherwise noted, survey results for “Asian Americans” and “U.S. Asians” refer to adults living in the United States, whether U.S. citizens or not U.S. citizens and regardless of immigration status. Both terms are used interchangeably. Adults refers to those ages 18 and older.

U.S. Asian groups, subgroups, heritage groups and country-of-origin groups are used interchangeably to reference respondent’s self-classification into “specific Asian groups.” This self-identification may or may not match a respondent’s country of birth or their parent’s country of birth.

Unless otherwise noted, whites include only non-Hispanic whites. Blacks include only non-Hispanic blacks. Hispanics are of any race. Asians can also be Hispanic.

Figures for the U.S. general public are based on nationally representative surveys of respondents of any race, including Asian. Thus, comparisons between U.S. Asians and the U.S. general public may understate or overstate the magnitude of differences between Asian Americans and Americans who are not Asian, due to the fact Asians are also part of the general public to which the comparison is made. The maximum possible size of such an effect would be equal to the size of the U.S. Asian population (5.5% of U.S. adults, according to the 2010 U.S. Census). The maximum possible size of such an effect would occur only if responses of Asian Americans and non-Asian Americans were completely different on a specific survey question. In addition, the magnitude of such an effect may be smaller than the maximum due to the tendency of most general public opinion surveys to underrepresent U.S. Asians with limited English proficiency.

Differences between groups or subgroups are described in this report only when the relationship is statistically significant and therefore unlikely to occur by chance. Statistical tests of significance take into account the complex sampling design used for this survey and the effect of weighting.

Roadmap to the Report

The remainder of the report is divided into six sections. First, it details the religious affiliation of Asian Americans as a whole and of the six largest subgroups (by country of origin). It also takes a closer look at Asian adults in the U.S. who have switched religions and those who have married someone from a different faith. The next sections discuss the importance of religion to Asian Americans, their religious beliefs and their religious practices. Finally, the report analyzes the social and political views of Asian Americans, primarily by looking at differences in attitudes among the main religious groups.

Footnotes:

3 Asian Americans are a diverse group in the United States. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “Asian” refers to a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent. The Asian population includes people who indicated their race(s) as “Asian Indian,” “Chinese,” “Filipino,” “Japanese,” “Korean,” “Vietnamese” or “Other Asian,” or wrote in entries such as “Pakistani,” “Thai,” “Cambodian” or “Hmong.” With growing diversity in the nation’s population, the Census Bureau has changed the wording of questions about race and ethnicity over time. Since Census 2000, respondents could select one or more race categories to indicate their racial identities. (About 15% of the Asian population reported multiple races in Census 2010.) In addition, since Census 2000, the Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander population, formerly included with the totals for the Asian population, has been counted as a separate race group. Because of these changes, caution is advised in historical comparisons on the racial composition of Asians. (return to text)

4 There are not enough survey respondents from these faiths for separate analysis. A total of 4% of U.S. Asians are Muslim. For more information on Muslims in the United States, see Pew Research Center. 2011. “Muslim Americans: No Sign of Growth in Alienation or Support for Extremism.” Washington, D.C.: August. See Appendix 1 of the current report for a comparison of U.S. Muslims and Asian-American Muslims on selected questions. (return to text)

5 The size of each U.S. Asian subgroup is based on the total U.S. Asian population, including single or mixed-race Asians. See Pew Research Center’s Social and Demographic Trends project. 2011. “The Rise of Asian Americans.” Washington, D.C.: June. (return to text)

6 Classification into country–of-origin groups is based on self-identification. This self-identification may or may not match a respondent’s country of birth or his/her parent’s country of birth. Respondents who identified their specific Asian group as Taiwanese or Chinese Taipei are classified as Chinese Americans in this report. (return to text)

7 For estimates of the number of Christians living in India and many other countries, see Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2011. “Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Christian Population.” Washington, D.C.: December. The Pew Global Attitudes survey of India in 2012 found 2% of the adult population to be Christian. See Appendix 2 of the current report. (return to text)

8 For more information on religion and migration around the world, see Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2012. “Faith on the Move: The Religious Affiliation of International Migrants.” Washington, D.C.: March. (return to text)

9 Asian Americans, on average, are younger and better educated than the U.S. population. The median age among Asian Americans is 41 years vs. 45 years for the U.S. adult population. And 49% of Asian Americans ages 25 and older have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with 28% of all U.S. adults ages 25 and older. See Pew Research Center’s Social and Demographic Trends project. 2011. “The Rise of Asian Americans.” Washington, D.C.: June. (return to text)

10 For more information on restrictions on religion in China and other countries around the world, see Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2011. “Rising Restrictions on Religion.” Washington, D.C.: August. (return to text)

11 The figures for switching are not directly comparable between the two surveys because they used slightly different approaches to categorizing religious affiliation. (return to text)

12 For details, see Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. Conducted in 2007, published in 2008. “U.S. Religious Landscape Survey.” Washington, D.C.: February. (return to text)

13 These intermarriage rates do not count a marriage across Protestant denominational lines—for example, between a Baptist and a Lutheran—as a religiously mixed marriage. But they do treat a marriage between a Protestant and a Catholic, or a marriage between a person who is religiously affiliated and one who is not, as religiously mixed. (return to text)

14 The figures for interfaith marriage are not directly comparable between the two surveys because they used slightly different approaches to categorizing religious affiliation. For more information on religious intermarriage in the U.S. general public, see Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. Conducted in 2007, published in 2008. “U.S. Religious Landscape Survey.” Washington, D.C.: February. (return to text)

15 See, for example, Desai, Sonalde B., et al. 2010. “Human Development in India: Challenges for a Society in Transition.” New Delhi: Oxford University Press, January. (return to text)

16 Nearly four-in-ten Vietnamese immigrants (38%) cite political conflict or persecution as the main reason they came to the United States, a higher figure than among any of the other five largest country-of-origin groups. See Pew Research Center’s Social and Demographic Trends project. 2011. “The Rise of Asian Americans.” Washington, D.C.: June. (return to text)

17 According to the Pew Forum’s “U.S. Religious Landscape Survey,” conducted in English and Spanish in 2007 and published in 2008, for example, 48% of U.S. Buddhists are college graduates, and 39% report an annual household income of at least $75,000. (return to text)

18 Classification of Asian-American Protestants into evangelical and mainline is based on self-identification as born-again or evangelical, regardless of Protestant denomination. For more details see Chapter 1 “Religious Affiliation.” (return to text)

19 Precise population figures for the religious composition of the U.S. general public are not available because the U.S. Census Bureau, as a matter of policy, does not track religious affiliation. All estimates of the religious composition of the U.S. general public are based on representative-sample surveys. These estimates are complicated by the fact that such surveys typically rely on English-language, or English and Spanish-language, interviewing. As such, they are likely to underestimate the size of groups with limited English proficiency, including those speaking Asian languages. The Pew Forum’s estimates of the size and composition of U.S. Buddhists and Hindus, respectively, are based on combining Census data on the size of the total adult population with survey estimates of the percentage of Asian Americans in each religious group from the 2012 Survey of Asian Americans, as well as survey estimates of the percentage of each religious group that does not identify as Asian race from aggregated Pew Research Center surveys conducted between 2010 and June 2012. (return to text)

Photo Credits from left to right: © Radius Images/Corbis, © Image Source/Corbis, Istockphoto and © 2010 Getty Images