A rising share say they have no religion, but many consider themselves close to one or more religious traditions for reasons such as family or culture

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand the religious identities, experiences and practices of people of Asian origin or ancestry living in the United States. The study is part of the Center’s multiyear research effort focused on the nation’s Asian population. Its centerpiece is a nationally representative survey of 7,006 Asian adults. The survey sampled U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic ethnicity. It was offered in six languages: Chinese (Simplified and Traditional), English, Hindi, Korean, Tagalog and Vietnamese. Responses were collected from July 5, 2022, to Jan. 27, 2023, by Westat on behalf of Pew Research Center.

The survey includes a large enough sample to report on the views of the six biggest origin groups among Asian Americans: Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese. Together, these six groups constitute 81% of all U.S. Asian adults, according to a Center analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2021 American Community Survey (ACS). These six groups are discussed throughout the report.

Findings for Asian origin groups other than the six largest are also included in the report – in the survey findings for U.S. Asian adults overall, and in findings about the “NET East Asian,” “NET South Asian” and “NET Southeast Asian” populations. Origin groups other than the six largest each comprise about 2% or less of the Asian population in the U.S., making it challenging to recruit nationally representative samples for any of them.

Survey respondents were drawn from a national sample of residential mailing addresses, which included addresses from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Specialized surnames list frames maintained by the Marketing Systems Group were used to supplement the sample. Those eligible to complete the survey were offered the opportunity to do so online or by mail with a paper questionnaire. For more details, read the survey Methodology. For questions used in this analysis, refer to the Topline Questionnaire.

In addition to the survey results, the report draws on guided small group discussions (focus groups) and in-depth one-on-one interviews. Details on these can be found in the focus group Methodology.

Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. The Center’s Asian American portfolio was funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts, with generous support from The Asian American Foundation; Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; the Henry Luce Foundation; the Doris Duke Foundation; The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation; The Dirk and Charlene Kabcenell Foundation; The Long Family Foundation; Lu-Hebert Fund; Gee Family Foundation; Joseph Cotchett; the Julian Abdey and Sabrina Moyle Charitable Fund; and Nanci Nishimura.

We would also like to thank the Leaders Forum for its thought leadership and valuable assistance in helping make this survey possible.

The qualitative research on Asian American Muslims, and the strategic communications campaign used to promote the research portfolio, were made possible with generous support from the Doris Duke Foundation.

Asians living in the United States/U.S. Asian population/Asian Americans: Used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Asian, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

Ethnicity/Ethnic origin labels: Used interchangeably in this report for findings for ethnic origin groups, such as Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean or Vietnamese. For this report, ethnicity is not nationality. For example, Chinese in this report are those self-identifying as of Chinese ethnicity, rather than necessarily being a current or former citizen of the People’s Republic of China. Ethnic origin groups in this report include those who self-identify as one Asian ethnicity only, either alone or in combination with a non-Asian race or ethnicity.

Less populous Asian origin groups/Other Asian origin groups: In this report, those who self-identify with ethnic origin groups other than the six largest Asian origin groups (e.g., those who identify as Burmese, Hmong or Pakistani). The term includes those who identify with only one Asian ethnicity. These ethnic origin groups each represent about 2% or less of the overall Asian American population and are unreportable on their own due to small sample sizes. They are collectively reportable under this broader category.

Asian origins/Asian origin groups: Used interchangeably throughout this report to describe ethnic origin groups.

Immigrant: Someone who was not a U.S. citizen at birth – in other words, someone born outside the U.S., Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents who are not U.S. citizens. Also referred to as “foreign born” in this report.

U.S. born: Those born in the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.

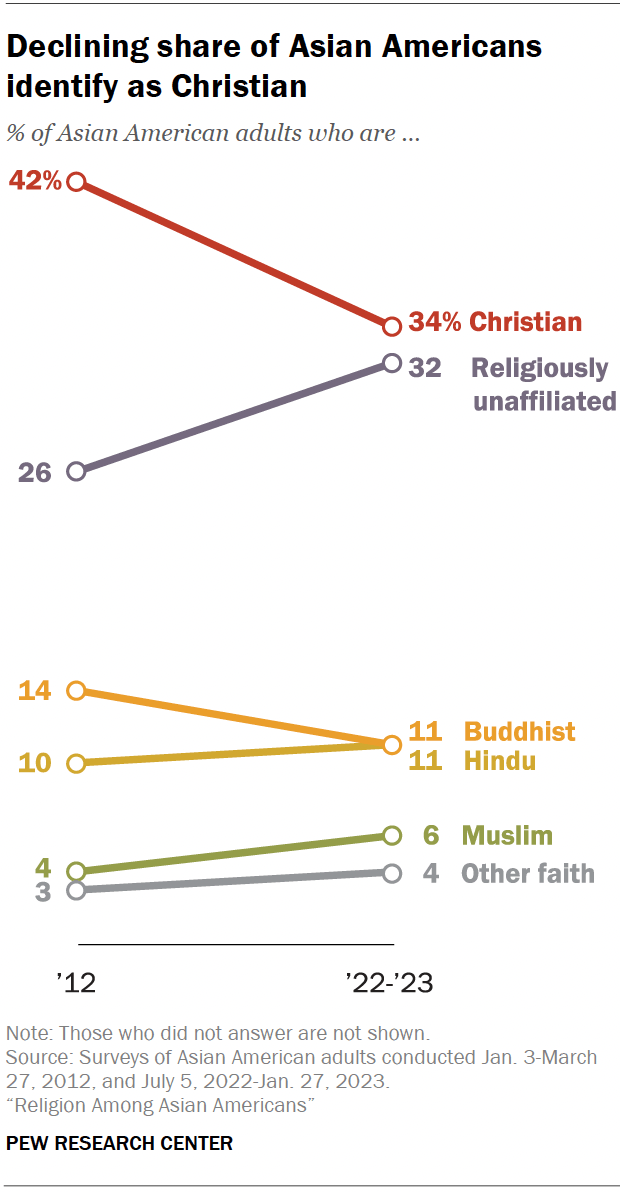

Like the U.S. public as a whole, a growing percentage of Asian Americans are not affiliated with any religion, and the share who identify as Christian has declined, according to a new Pew Research Center survey exploring religion among Asian American adults.

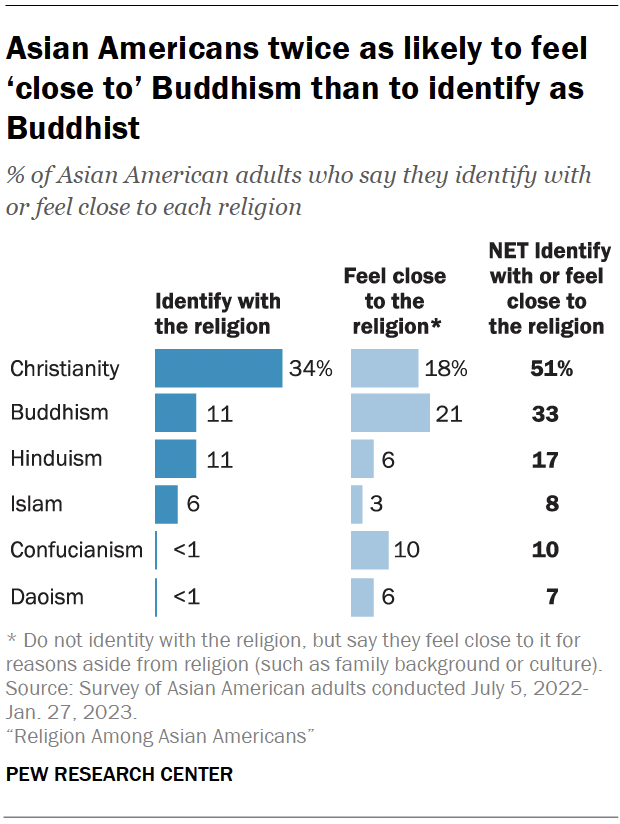

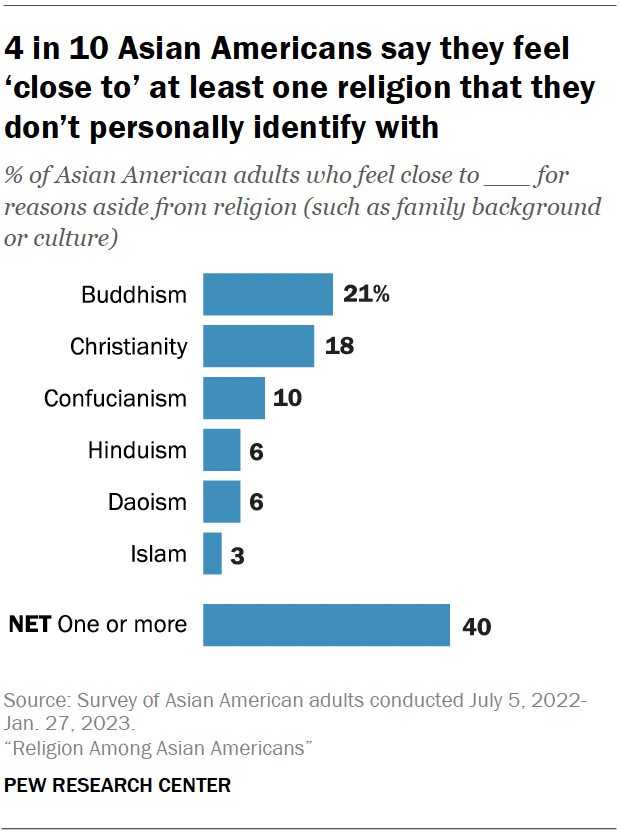

But the survey also shows that 40% of Asian Americans say they feel close to some religious tradition for reasons aside from religion. For example, just 11% of Asian American adults say their religion is Buddhism, but 21% feel close to Buddhism for other reasons, such as family background or culture.

Religious profile of Asian Americans

- Today, 32% of Asian Americans are religiously unaffiliated, up from 26% in 2012.

- Christianity is still the largest faith group among Asian Americans (34%).

- But Christianity has also seen the sharpest decline, down 8 percentage points since 2012.

- Asian American Christians are about evenly split between Catholics and Protestants (17% and 16% of all U.S. Asian adults, respectively). Born-again or evangelical Protestants make up 10% of Asian Americans.

- Buddhists and Hindus each account for about one-in-ten Asian Americans, while Muslims make up 6%.

- Various other religious groups (including Daoists, Jains, Jews, Sikhs and others) together make up about 4% of all Asian American adults.

Jump to chapters on …

- Asian American Christians

- Asian American Buddhists

- Asian American Hindus

- Asian American Muslims

- Confucianism and Daoism among Asian Americans

- Asian Americans who are religiously unaffiliated

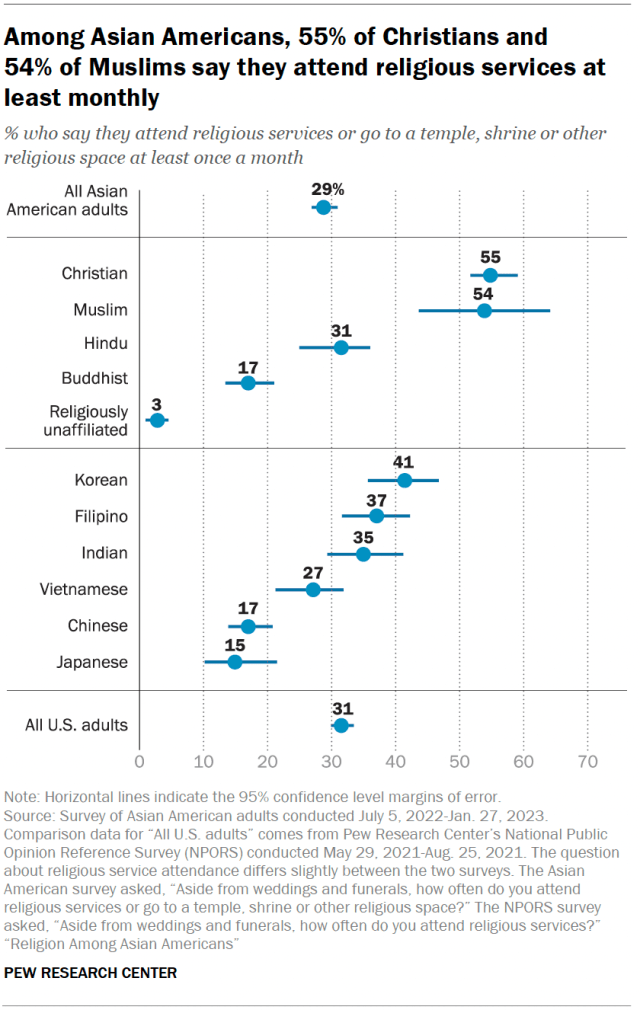

The survey also asked Asian Americans how important religion is in their lives (31% say it is very important), how often they attend religious services (29% report that they go at least monthly), and whether they have an altar, shrine or religious symbol that they use for home worship (36% say they do).

Of the major Asian American religious groups, Protestants and Muslims are the most likely to report that they attend religious services at least once a month. By contrast, Buddhists and Hindus are especially likely to say they worship at shrines or altars in their homes.

Differences in religious affiliation among Asian origin groups

There are large differences in religious affiliation among Asian Americans depending on their ethnic origin group. For example:

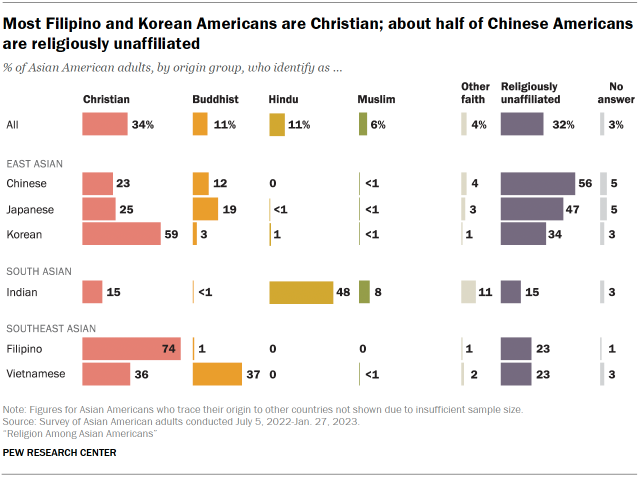

- 56% of Chinese Americans and 47% of Japanese Americans are not affiliated with any religion – the highest percentages of “nones” among the Asian origin groups that are large enough to be analyzed in the survey.

- Three-quarters of Filipino Americans are Christian, mostly Catholic.

- 59% of Korean Americans are Christian, mostly Protestant – including 34% who identify as born-again or evangelical Protestants.

- Indian Americans are far more likely than the other large Asian origin groups to be Hindu (48%), though a fair number of Indian Americans are Christian (15%), Muslim (8%) or Sikh (8%).

- Vietnamese Americans are the most likely of the large origin groups to identify as Buddhist (37%).

These six Asian origin groups – Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese Americans – account for 81% of all Asian Americans.1

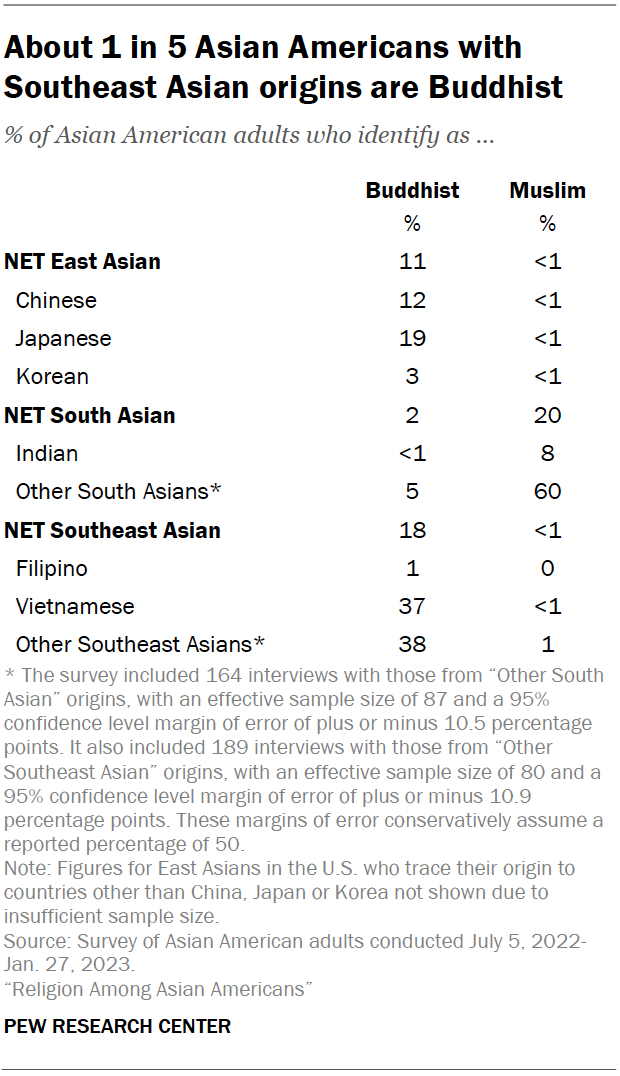

The survey did not include enough interviews with respondents in other Asian origin groups to be able to report on them separately. However, the members of less populous Asian origin groups were included in the study, and it is possible to analyze them when they are grouped together by region. Doing this reveals some additional patterns. For example:

- 60% of South Asians in the United States other than Indian Americans (i.e., those who trace their origins to countries including Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan) are Muslim – higher than any of the six largest Asian origin groups.

- 38% of U.S. adults who trace their origin to Southeast Asian countries other than the Philippines and Vietnam are Buddhist.

These are among the key findings of a nationally representative, multilingual survey of 7,006 Asian American adults conducted by Pew Research Center from July 5, 2022, to Jan. 27, 2023. The Center previously has published other findings from this survey. 2

Importance of religion

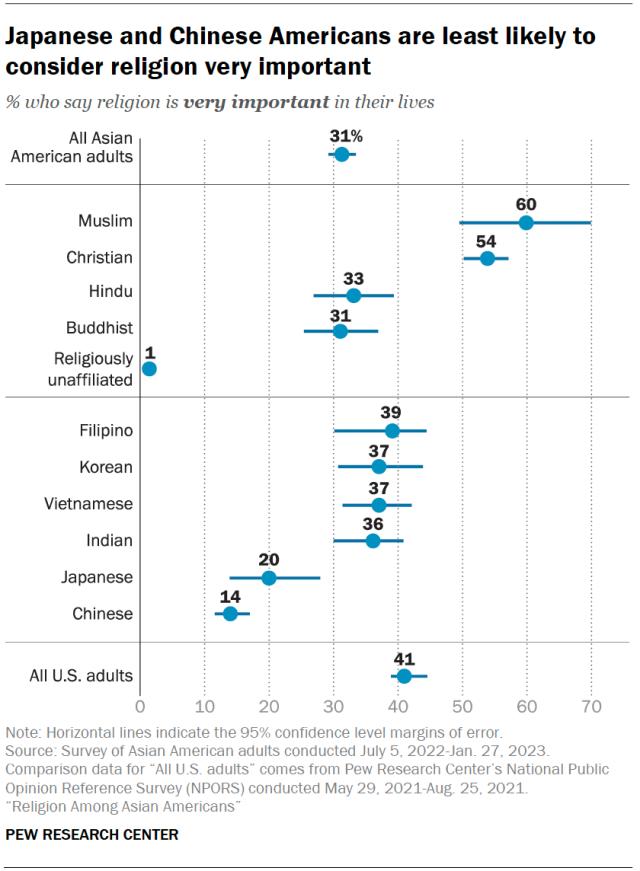

While nearly a third of Asian Americans say religion is very important in their lives, Asian American Muslims (60%) and Christians (54%) are much more likely than Asian American Hindus (33%) and Buddhists (31%) to feel that way.

Looking at Asian Americans by their ethnic origin group, Japanese and Chinese Americans are notably less likely than members of other Asian origin groups to say religion is very important in their lives, reflecting the large number of “nones” (those who describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”) in these two groups.

As a whole, Asian Americans born in the U.S. are somewhat less likely than Asian Americans born elsewhere to say religion is very important in their lives. And Asian Americans overall are somewhat less likely than the general U.S. population to say religion is very important in their lives (31% vs. 41%).

Attending religious services

About three-in-ten Asian Americans (29%) say they attend religious services or go to a temple, shrine or other religious space at least once a month, including 21% who say they do so weekly or more often.

Asian American Christians and Muslims are more likely than Asian American Buddhists, Hindus or “nones” to say they attend religious services at least monthly.

Regular religious attendance is more common among Korean and Filipino Americans than among Vietnamese, Japanese or Chinese Americans. (As previously noted, Korean and Filipino Americans are also more likely to be Christian.)

Overall, foreign-born Asian Americans are more likely than those born in the U.S. to attend religious services at least monthly (32% vs. 21%).

On this question, Asian Americans closely resemble U.S. adults as a whole, 31% of whom say they attend religious services at least once a month, including 25% who say they do so weekly or more often, according to an August 2021 survey.

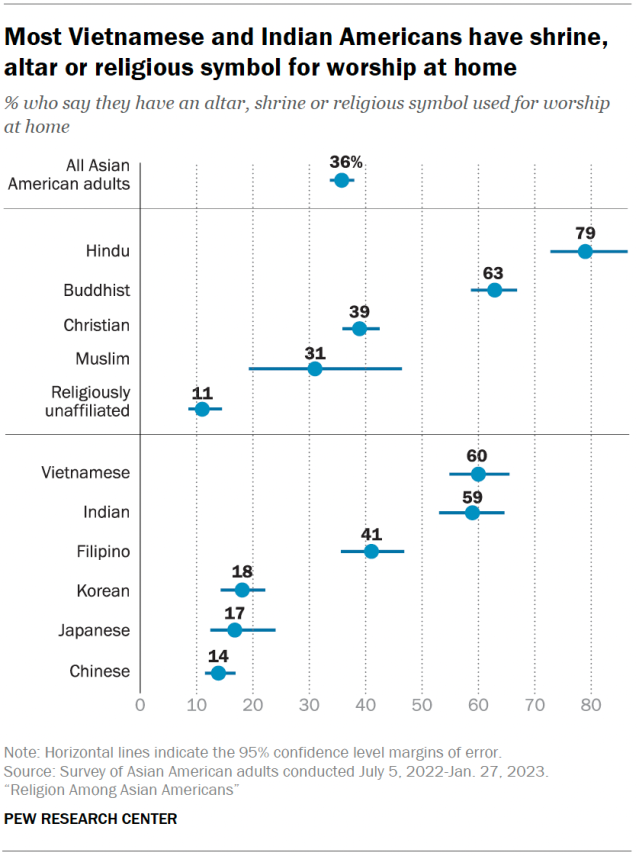

Home worship: Shrines, altars and religious symbols

In some Asian religious traditions, religious practice is centered in the home rather than in a communal setting. About one-third of Asian Americans (36%) say their home contains an altar, shrine or religious symbol that they use for worship.

Using an altar, shrine or other religious symbol for worship in the home is most common among Vietnamese and Indian Americans, in part because this is a relatively common practice among Buddhists (who make up 37% of the Vietnamese American population) and Hindus (who make up 48% of the Indian American population).

Worshipping at home is also fairly common among Filipino Americans, owing to the large share of Catholics within the Filipino American population – 66% of Filipino Catholics in the U.S. say they have an altar, shrine or religious symbol used for worship in their home, compared with just 9% of other Filipino Americans.

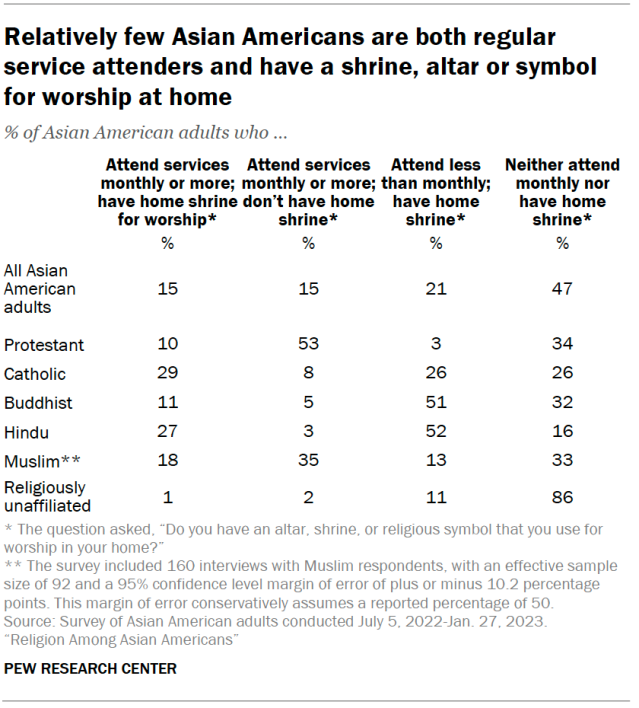

While 36% of Asian Americans say they use a shrine, altar or religious symbol to worship at home, and 29% say they regularly attend religious services, only 15% say they do both of these things. This pattern reflects the varying worship practices of different religious groups.

For example, about half of Asian American Protestants (53%) say they attend religious services monthly but don’t worship at a home altar. About half of Buddhists (51%) and Hindus (52%) say the opposite: They do not attend religious services monthly, but they do worship at a home altar.

Sizable numbers of Asian American Catholics (29%) and Hindus (27%) engage in both practices, attending religious services monthly and worshipping at a home altar or shrine.

Feeling ‘close to’ a religion for reasons such as family background or culture

In the U.S., being Christian is often perceived as an exclusive religious identity with a clear set of associated beliefs (such as a creed) and normative practices (such as attending religious services). In many Asian countries, however, religion and religious identity are often understood differently.3

For example, the practices and beliefs associated with Buddhism, Hinduism, Daoism (or Taoism), Shintoism and Confucianism are often so infused in daily life in Asian countries that even people who do not identify with those religious groups may accept some of their beliefs and engage in some of their rituals.

The lines between members and nonmembers, as well as between the religious groups themselves, can be fuzzy. In China and Japan, for example, many individual temples and shrines are associated with multiple traditions. (Read the sidebar about the words for “religion” in Asian languages.)

Asian Americans are at the intersection of these two ways of being religious. Many identify with a specific religion, such as Christianity or Islam. However, many who do not identify with a specific religion still say they consider themselves close to the religious or philosophical traditions that are common in their country of ancestry. In addition, some Asian Americans say they feel close to multiple faith traditions.

The survey measured these ways of being religious with two questions. The first asked: “What is your present religion, if any?”4 The second question asked: “Aside from religion, do you consider yourself close to any of the following traditions for other reasons (such as your family background or culture)?”5

In total, 40% of Asian American adults express a connection to one or more groups that they do not claim as a religious identity.

For example, 21% of Asian American adults do not identify religiously as Buddhist but say they feel close to Buddhism “aside from religion,” while 18% do not identify religiously as Christian, yet say they feel close to Christianity aside from religion. And 10% express a similar connection to Confucianism.

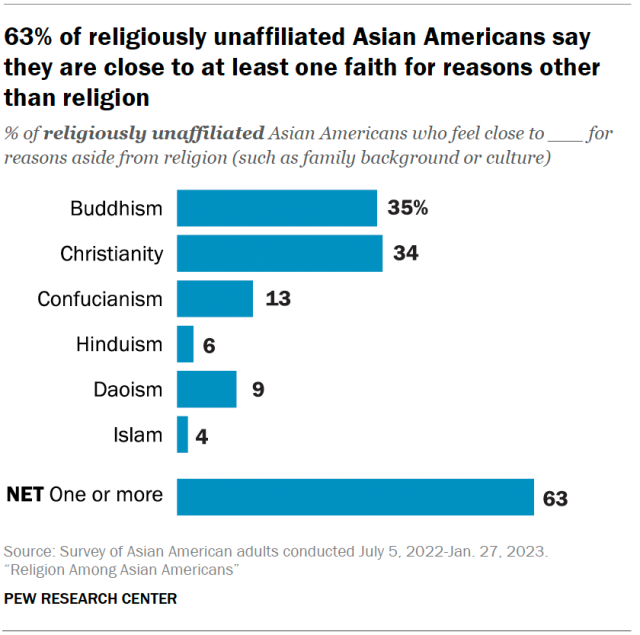

About two-thirds of religiously unaffiliated Asian Americans (63%) say they are close to at least one of these religious traditions. (Jump to the chapter on religiously unaffiliated Asian Americans for more on this.)

The meaning of ‘religion’ in East Asia

In many East Asian languages, there is no single, literal equivalent of the English word “religion.” The modern Chinese, Japanese and Korean terms for religion – zongjiao, shūkyō and jonggyo – were all created in the early 20th century by Asian scholars working with Western texts who wanted to translate “religion” from Western languages and needed to invent a word.

Their definitions of religion were influenced by Christian religious norms, rather than developing organically from Buddhist, Confucian, Shinto, Daoist or other religious traditions that are more common in those countries, as we noted in our 2023 report, “Measuring Religion in China.”

To this day, the words for “religion” in many East Asian countries and some parts of Southeast Asia refer primarily to organized forms of religion, particularly those with professional clergy and institutional oversight. The Chinese term zongjiao and its Japanese and Korean equivalents do not typically refer to some traditional religious beliefs and practices that are common in these countries.

Across East Asia, there are many beliefs (such as in spirits) and practices (such as visiting shrines and making offerings to ancestors) that might be considered religious, broadly speaking. But there is little emphasis in these countries on membership in congregations or denominations, except among Christians and Muslims.

These differences might lead Americans of East Asian origin to say they do not identify with any religion or that religion is not very important in their lives, because they do not consider their traditional spiritual practices – or cultural customs that have a spiritual underpinning – to be “religious” in nature. In a series of small group conversations, some focus group participants made this point. And the survey data supports it: More Asian Americans say they are close to Buddhism for reasons such as ancestry or culture than say Buddhism is their religion.

A similar dynamic exists in Asian countries. In China, for example, the share of adults who consider Buddhism to be their formal religion (zongjiao) is 4%, according to the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey data. But the share who believe in Buddha and/or bodhisattvas is 33%, according to the 2018 China Family Panel Studies survey.

Findings from our focus groups

After conducting the survey, the Center arranged small group conversations (focus groups) and one-on-one interviews with a total of more than 100 Asian Americans to gain an understanding of what religion means to them in their own words.6 In the conversations, participants were asked to discuss the nature of their connections to religions they may not claim as their own.7

These are some of the most common themes that emerged on this topic:

Many people we talked to, including those who are religiously unaffiliated, expressed a cultural connection to the dominant religious tradition in their country of origin. This sentiment was also apparent in the survey results, which show, for example, that Indian Americans who are religiously unaffiliated say they feel close to Hinduism aside from religion at much higher rates than do religious “nones” of other Asian origin groups.

For some non-Christians we talked to in these conversations, feeling close to Christianity is an unavoidable result of living in the United States. One Indian American focus group participant who grew up in the U.S. and is not Christian, but who said she considers herself close to Christianity, explained: “My whole life I was exposed to Christmas and all this stuff. Even though I don’t believe in it, we had to give gifts … so it was always part of our culture, even though we don’t believe in it.” In the survey, 34% of religiously unaffiliated U.S. Asian adults (representing 18% of Asian Americans overall) said they feel close to Christianity even though they do not identify as Christians.

Some participants in these conversations said there is a natural affinity or closeness between certain pairs of religions that have shared beliefs, values or practices. For example, a Hindu participant expressed a personal connection to Buddhism “because some of the practices of Buddhists, they are very much similar to [Hindu practices].” And a Muslim participant drew parallels between Islam and Christianity, saying “in Islam and in Christianity there’s a lot common.”

Finally, some people we talked to questioned whether Confucianism or Daoism should be seen as religions. In the words of one Vietnamese Buddhist, “Confucianism and Daoism is part of my culture. However, for me, it’s a school of philosophy. I do not identify myself as being a Daoist or Confucian.” Another participant said of Confucianism, “There’s no deity there. So it’s only … a philosophy.” This view aligns with the survey’s findings on Asian Americans’ views on Confucianism and Daoism. (Jump to the chapter on Confucianism and Daoism.)

Other key findings

In addition to the overall religious profiles of Asian American ethnic groups, other key findings from the survey include:

- 12% of Asian Americans neither identify with, nor feel close to, any of the religions or philosophical traditions measured in the survey.

- 30% of Asian Americans say all or most of their friends have the same religion they do. This share is slightly lower among Buddhists (21%) than among Asian Americans in other religious groups analyzed.

- 77% of Asian Americans say they would be comfortable if a family member married outside of their faith. This is slightly lower than the share saying they would be comfortable if a family member married someone who is not Asian (86%) or married someone who is Asian but has a different ethnicity (87%). Korean Americans are less likely than other Asian Americans to say they would be comfortable with a family member marrying outside of their faith.

The remainder of this report details the survey’s findings about Asian American adults who identify with – or feel close to – six religions or philosophical traditions. Click the links below to jump to each chapter.

Christianity | Buddhism | Hinduism | Islam | Confucianism and Daoism | Religiously unaffiliated