Compared with the parent who took the survey before them, U.S. teens are less likely to rate religion as a priority in their lives and to say they believe in God with absolute certainty. Still, a majority of teens say that religion is at least somewhat important in their lives, including one-in-five unaffiliated teens who say this.

In addition, more than eight-in-ten American adolescents say they believe in God or a universal spirit. Teens who identify as religiously affiliated are far more likely to believe in a supreme being than religious “nones,” but even most religiously unaffiliated teens express belief in a higher power – albeit with less certainty than teens who adhere to a particular faith group.

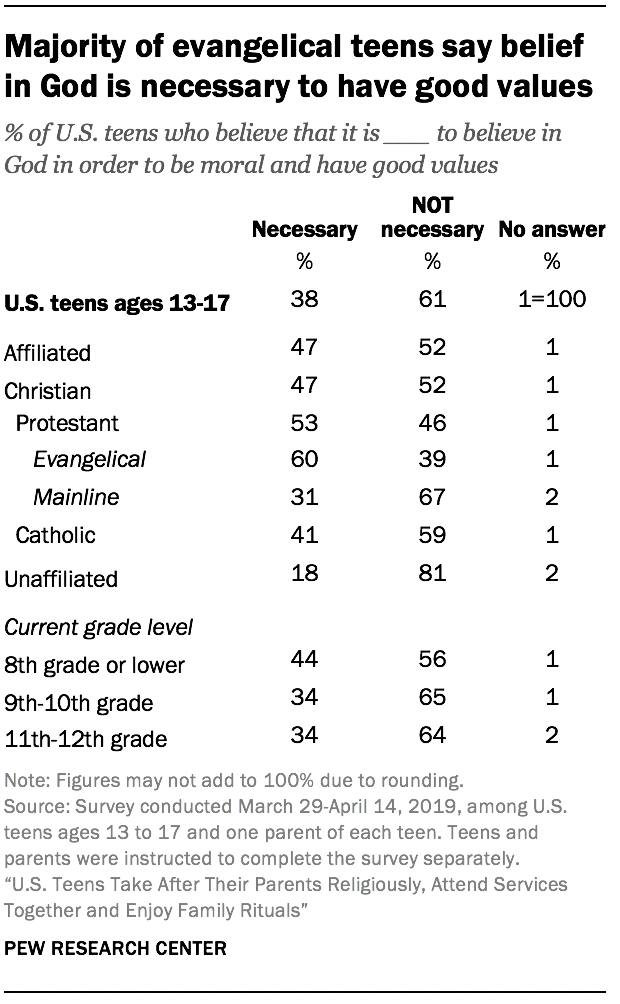

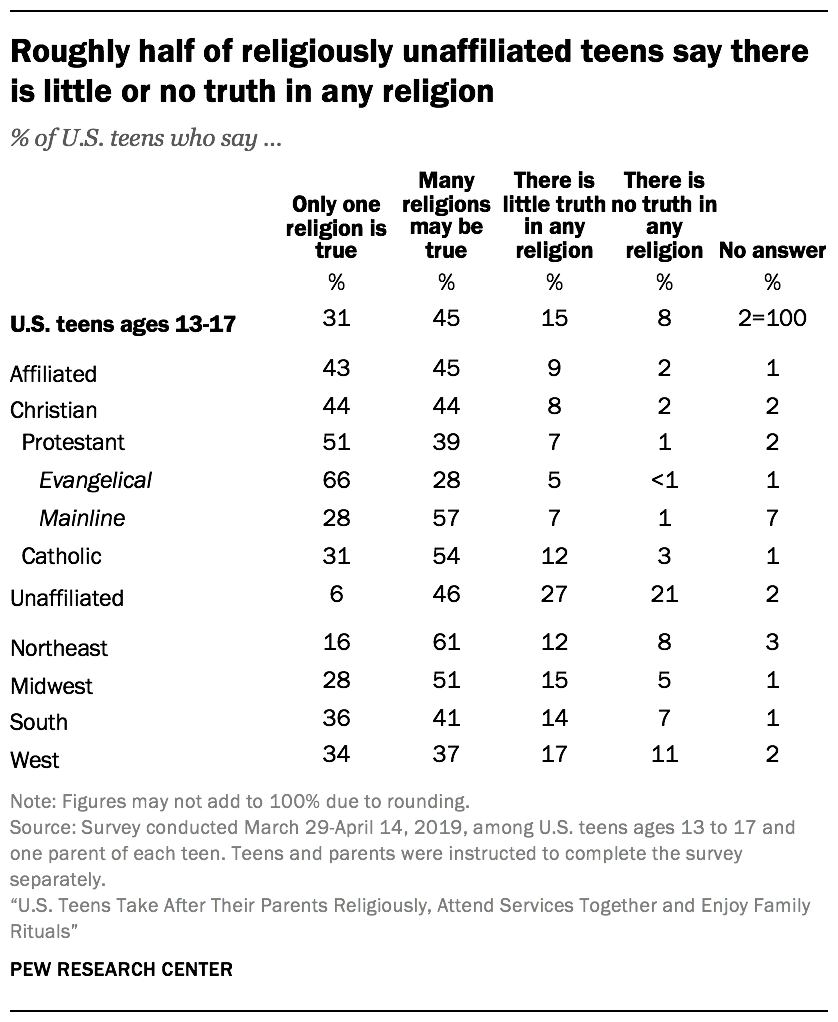

At the same time, many teens also espouse a view of morality that is not God-centric, and have a pluralistic view of religion in general. Like U.S. adults overall, a majority of adolescents say that it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values, and this holds true across most religious groups analyzed in this report – with the exception of evangelical Protestants. Furthermore, teens are more likely to say that “many religions may be true” than they are to say that “only one religion is true,” demonstrating a certain religious open-mindedness. Evangelical teens are again the exception: A majority say that only one religion is true.

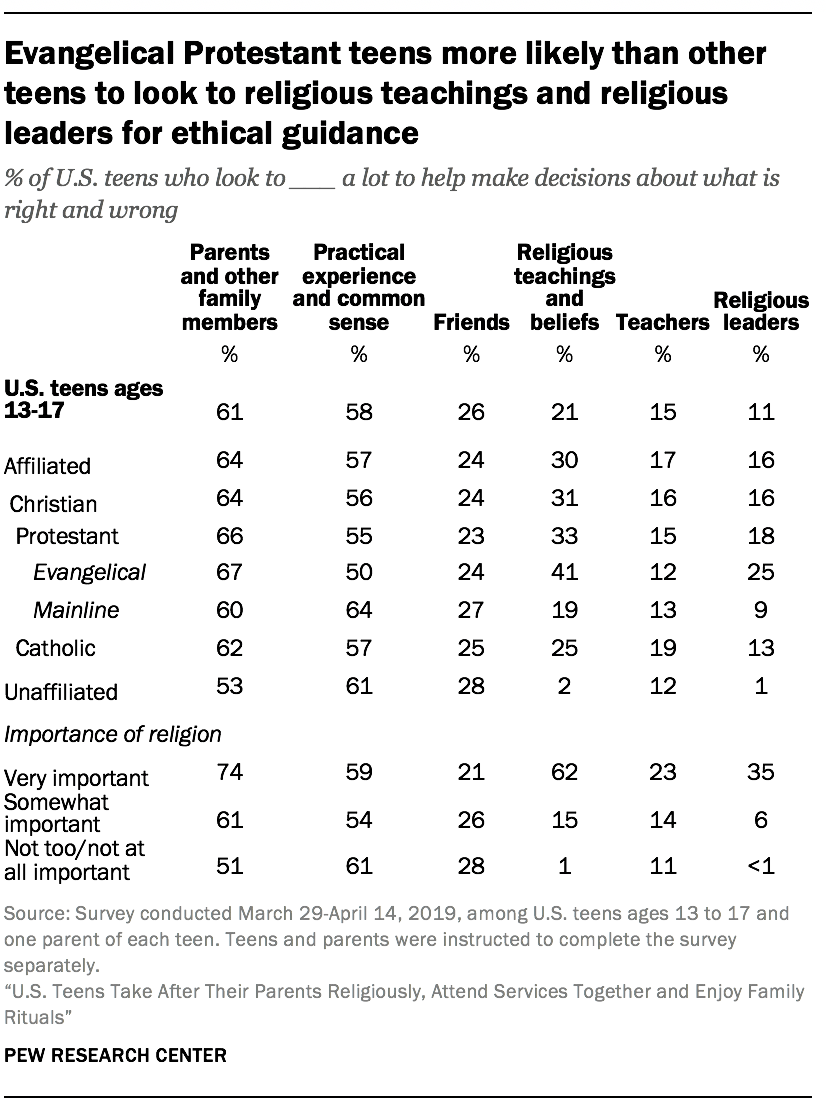

The survey also asked teens where they turn for moral and ethical guidance. This chapter shows that while religion is an important source of ethical decision-making for some American adolescents, on the whole they say it is far less important to making ethical decisions than are parents and other family members as well as practical experience and common sense. Evangelical teens are more likely than those in other religious groups analyzed in this study to rely on religious institutions to help them sort out right from wrong.

Teens less likely than parents to say religion is important in their lives

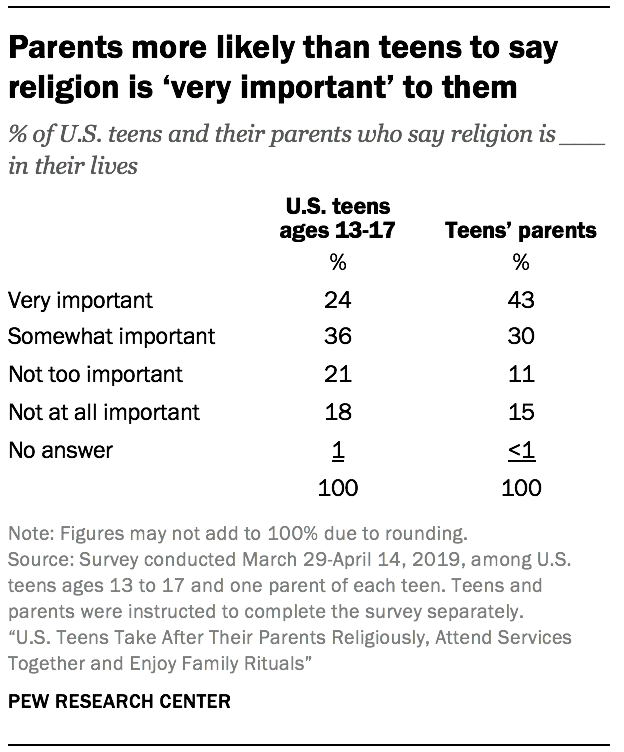

Most U.S. teenagers ages 13 to 17 say that religion is at least somewhat important in their lives, including 24% who say it is “very” important and 36% who say it is “somewhat” important, while 21% say religion is “not too” important in their lives and 18% say it is “not at all” important.

Most U.S. teenagers ages 13 to 17 say that religion is at least somewhat important in their lives, including 24% who say it is “very” important and 36% who say it is “somewhat” important, while 21% say religion is “not too” important in their lives and 18% say it is “not at all” important.

The responding parents in the survey are more likely than teens to say that religion is very important in their lives. About four-in-ten say this (43%), and an additional 30% say religion is somewhat important to them.

Looking at responses together, 44% of teens rate religion’s importance in their life differently than their parents do for themselves. And among all those who don’t align, 54% of these pairings include parents who say religion is very important in their own lives while their teen says it is less important.

Looking at responses together, 44% of teens rate religion’s importance in their life differently than their parents do for themselves. And among all those who don’t align, 54% of these pairings include parents who say religion is very important in their own lives while their teen says it is less important.

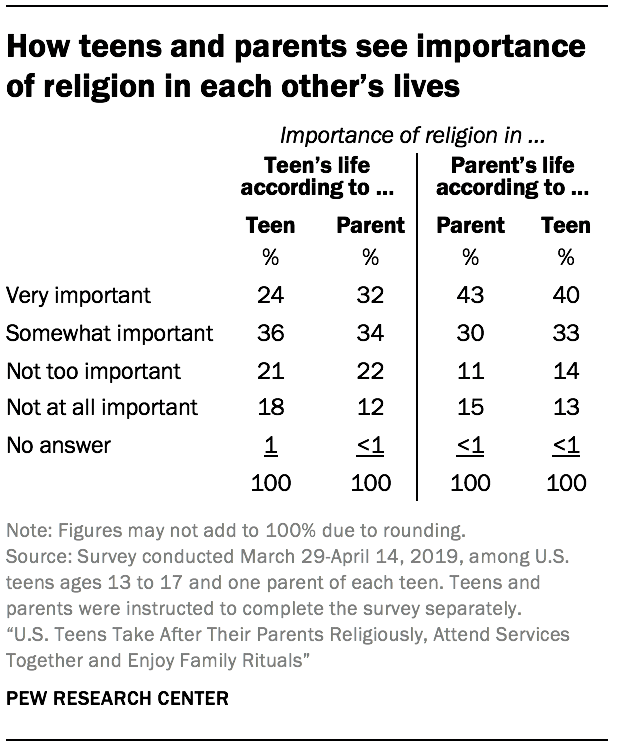

Furthermore, the survey asked each teen and parent how important they think religion is in the other person’s life. That is, teens were asked how important they think religion is in the life of the responding parent, and parents were asked the same about the responding teen.

Among teens, 40% say that religion is very important to their parent, compared with 43% among the parents who say the same of themselves. Among parents, 32% say that religion is very important to their teen, compared with 24% of teens who rank religion that highly in their own lives.

Among teens, 40% say that religion is very important to their parent, compared with 43% among the parents who say the same of themselves. Among parents, 32% say that religion is very important to their teen, compared with 24% of teens who rank religion that highly in their own lives.

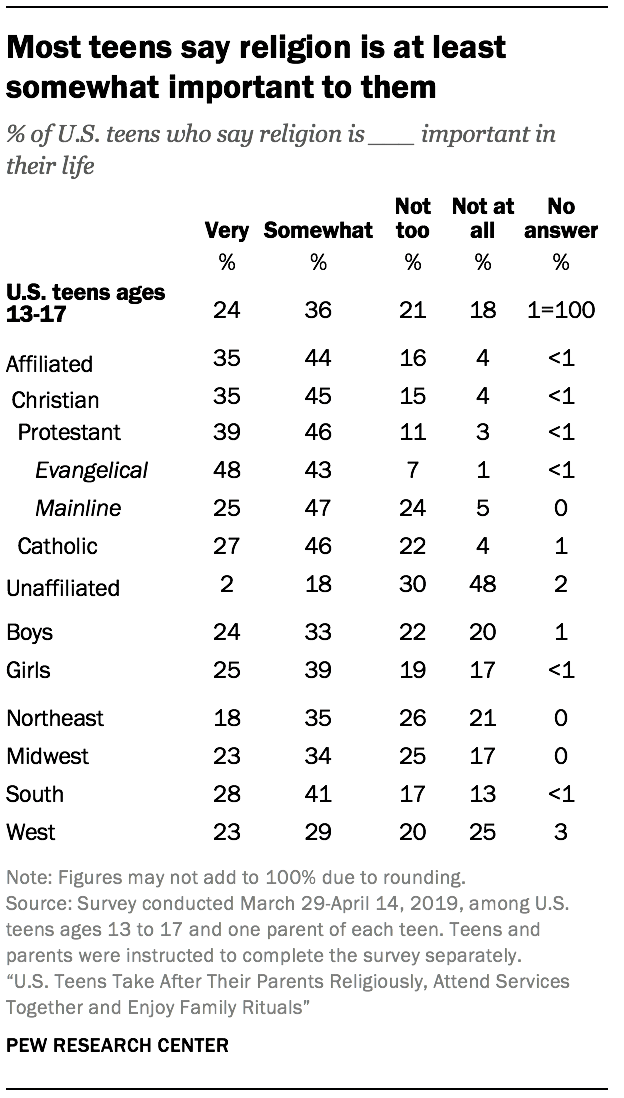

Evangelical teens are far more likely than the other religious groups analyzed to say that religion is very important in their lives. About half (48%) say this, compared with 27% among Catholic teens and 25% of mainline Protestant teens. By contrast, about half of religiously unaffiliated teens (48%) say that religion is not at all important in their lives.

Girls are more likely than boys to say that religion is very or somewhat important in their lives. Nearly two-thirds of girls (64%) say this, compared with 56% of boys.

Belief in God or a universal spirit

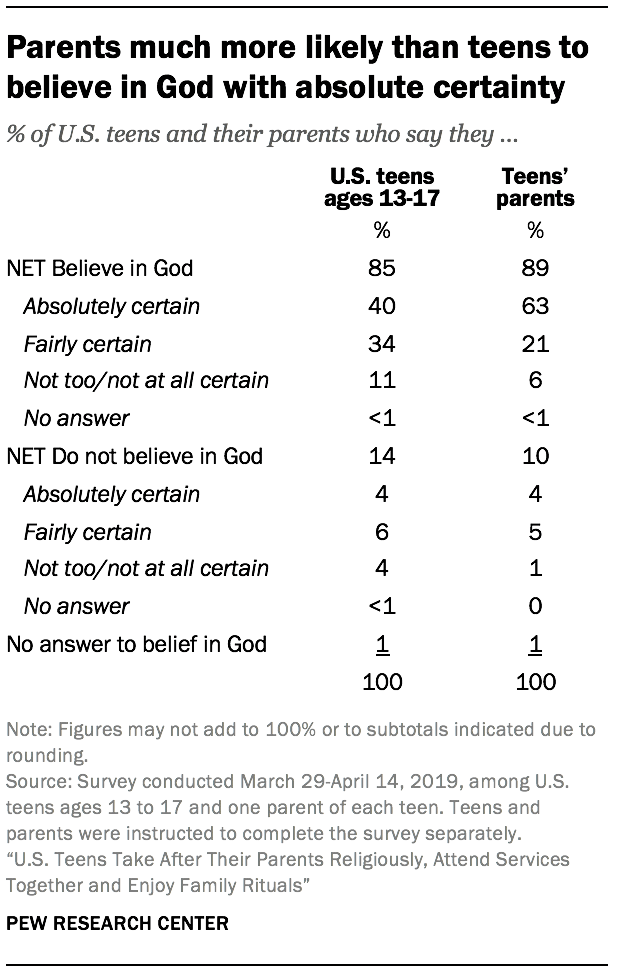

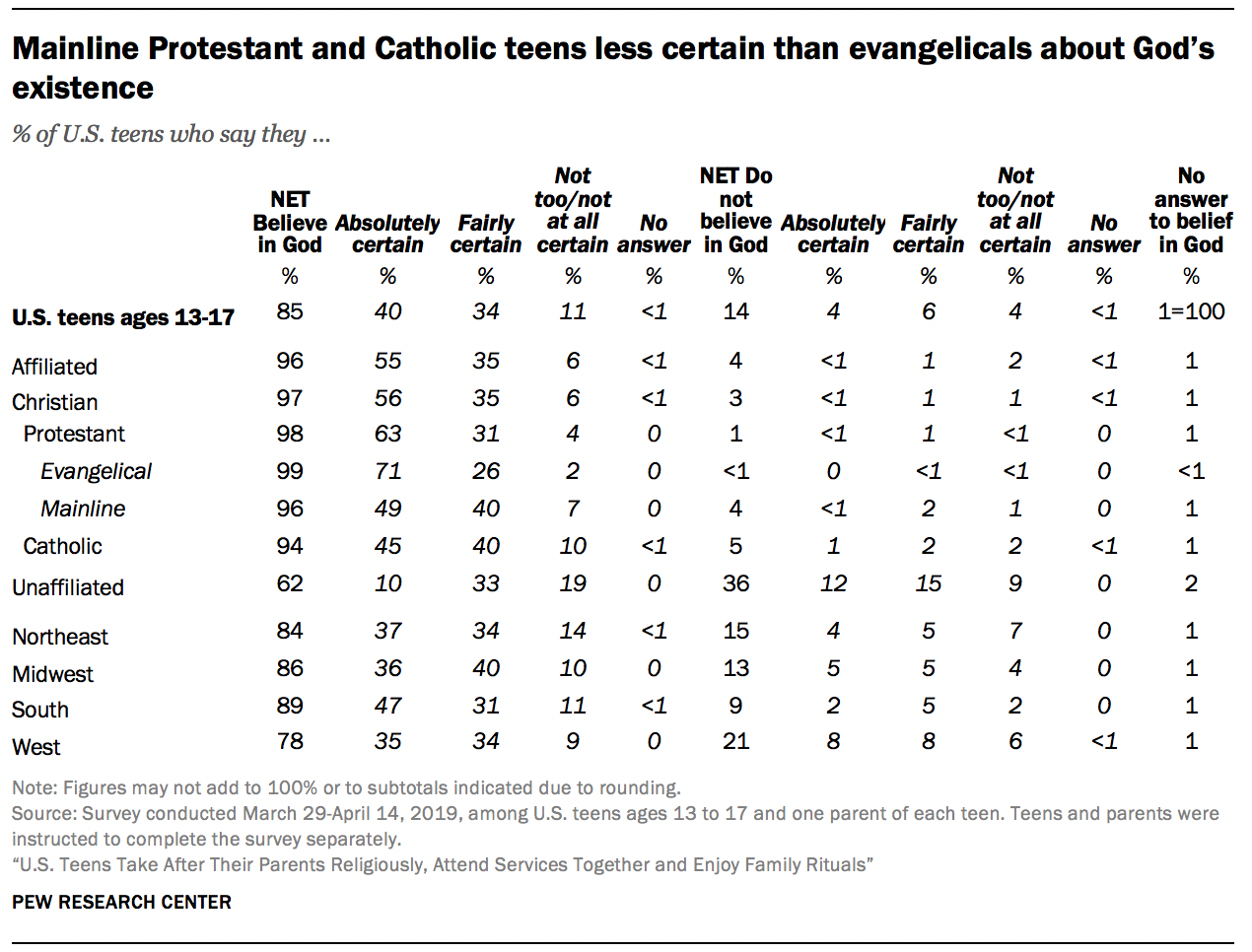

The vast majority (85%) of U.S. adolescents say they believe in God or a universal spirit, including 40% who are absolutely certain about this belief and 34% who are fairly certain. Just 14% say they do not believe in God, with 4% who say they are absolutely certain that God does not exist and 6% who are fairly certain on this matter.

The vast majority (85%) of U.S. adolescents say they believe in God or a universal spirit, including 40% who are absolutely certain about this belief and 34% who are fairly certain. Just 14% say they do not believe in God, with 4% who say they are absolutely certain that God does not exist and 6% who are fairly certain on this matter.

Among responding parents overall, roughly nine-in-ten express belief in God (89%). Compared with their teens, these parents are far more likely to be absolutely certain about this belief (63% vs. 40%).

Looking at overall belief in God – not accounting for certainty – the vast majority of teens (88%) give the same answer as their responding parent. And where there are mismatches in belief (for example, one person says they believe in God while the other does not), it fits with the broader pattern of lower levels of religiosity among teens. Among all teens who do not share the same beliefs about God as their responding parent, 62% say they do not believe in God, while their parent identifies as a believer – much larger than the share of teens who say that they believe in God and who have a parent who does not (24%). (The remainder include pairings in which either the teen or parent did not answer the question.)

More than nine-in-ten evangelical Protestant (99%), mainline Protestant (96%) and Catholic (94%) teens say they believe in God, but evangelicals stand out for their level of certainty. Seven-in-ten (71%) evangelical Protestant teens say they are absolutely certain that God exists. Far fewer mainline Protestants (49%) and Catholics (45%) say the same.

Among teens who identify as religiously unaffiliated, there is more variation in responses. About six-in-ten (62%) say they believe in God or a universal spirit, but relatively few (10% of all religiously unaffiliated teens) say they are absolutely certain in that belief. An additional one-third of teenage “nones” say they are fairly certain that God exists, while one-in-five (19%) say that while they do believe in God, they are not too certain or not at all certain about it.

About a third of religious “nones” ages 13 to 17 (36%) say they do not believe in God or a higher power, with most in this group expressing at least a fair amount of certainty in this position. Roughly one-in-ten unaffiliated teens (9%) say they do not believe in God – but are not too or not at all sure about it.

Among teens, roughly eight-in-ten or more across each of the demographic groups analyzed in this study say they believe in God or a universal spirit, but there is some variation in the overall levels of belief and certainty they express. For example, roughly half of all teens who live in the South (47%) say they are absolutely certain about the existence of God, while teens in the Northeast (37%), Midwest (36%) and West (35%) are less likely to share this certainty. Adolescents in the South also stand out specifically from those in the West in terms of not believing in God: Just 9% of Southern teens hold this view, while 21% of teens in the West say the same.

Most teens say it is NOT necessary to believe in God to be a moral person

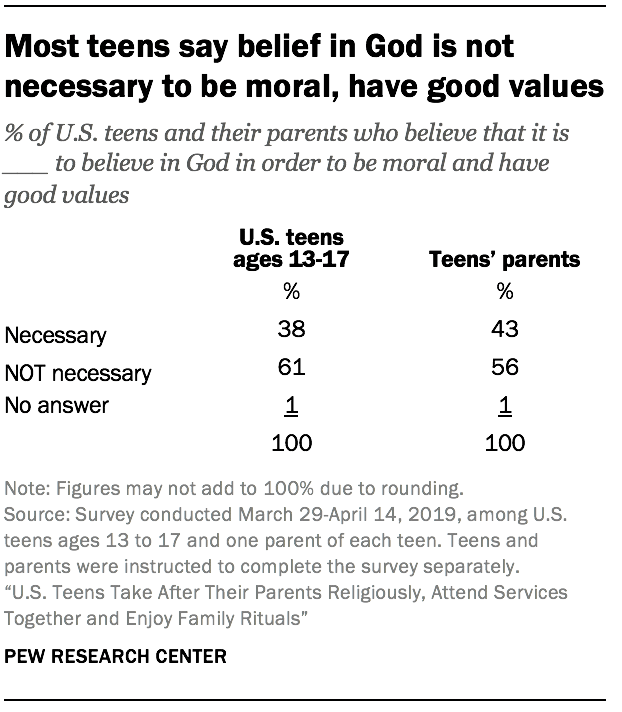

Overall, most U.S. teenagers ages 13 to 17 do not see belief in God as a prerequisite for having a moral compass. Six-in-ten adolescents (61%) express the view that it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values, while 38% say it is necessary.

Overall, most U.S. teenagers ages 13 to 17 do not see belief in God as a prerequisite for having a moral compass. Six-in-ten adolescents (61%) express the view that it is not necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values, while 38% say it is necessary.

Compared with their responding parents, teens are slightly less likely to cite belief in God as a prerequisite for good values. Among the responding parents, 43% say that it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values, while 56% hold the opposite view.

In fact, 20% of teens have an opinion on this question that does not align with that of their responding parent. Among those who misalign, 61% are teens who hold the view that it is not necessary to believe in God to have good values, while their responding parent disagrees. Half as many of teens (31% of those who give a different response from their parent) say it is necessary to believe in God to be moral, while their responding parent thinks it is not.

Among the specific religious groups analyzed in this study, evangelical Protestant adolescents stand out. They are the only group for which the balance tilts toward the opinion that it is necessary to believe in God to be moral (60% vs. 39%). By contrast, religiously unaffiliated teens are the most likely to hold the opposite view, that it is not necessary to believe in God in order to have good values (81%). And majorities of mainline Protestant (67%) and Catholic teens (59%) say the same.

Among the specific religious groups analyzed in this study, evangelical Protestant adolescents stand out. They are the only group for which the balance tilts toward the opinion that it is necessary to believe in God to be moral (60% vs. 39%). By contrast, religiously unaffiliated teens are the most likely to hold the opposite view, that it is not necessary to believe in God in order to have good values (81%). And majorities of mainline Protestant (67%) and Catholic teens (59%) say the same.

There also are some distinctions by grade level. Adolescents in high school are more likely than their younger peers to say it is possible to be a good person without believing in God. Roughly two-thirds of teens in 9th and 10th grade (65%) and in 11th or 12th grade (64%) express the opinion that it is not necessary to believe in God to be moral; a smaller majority (56%) of teens in 8th grade or below share this view.

Teens turn mostly to parents and other family, practical experience and common sense to determine right and wrong

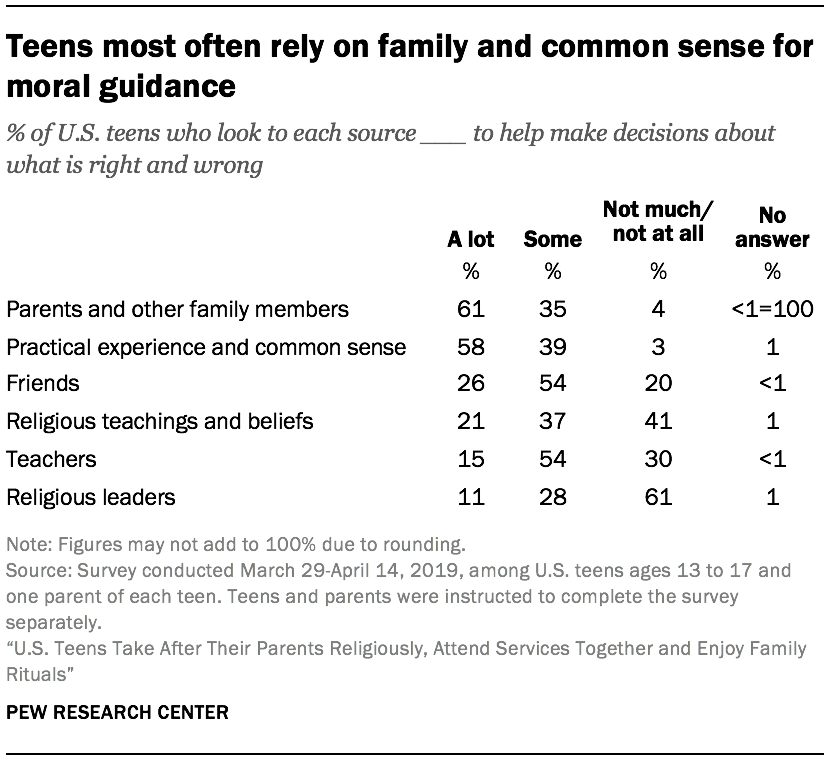

So where do teens turn when making decisions about what is right and wrong? Family and common sense appear to be most likely. About six-in-ten U.S. teens (61%) say that they look to parents and other family members “a lot” when making decisions about right and wrong. A similar proportion (58%) look to practical experience and common sense a lot. About a quarter (26%) of teens say they look a lot to friends when making decisions about what is right and wrong, and 15% rely on teachers.20

For most American teenagers, religion does not appear to be a primary source for addressing moral questions. About a fifth (21%) of adolescents say they look to religious teachings and beliefs a lot when making decisions about what is right and wrong, and only 11% say they look to religious leaders a lot. The shares of teens who look to religion “not much” or “not at all” when making moral decisions are particularly large relative to the other potential sources mentioned in the survey. Four-in-ten teens use little to no help from religious teachings and beliefs to make decisions about what is right and wrong, and about six-in-ten (61%) say the same about religious leaders.

For most American teenagers, religion does not appear to be a primary source for addressing moral questions. About a fifth (21%) of adolescents say they look to religious teachings and beliefs a lot when making decisions about what is right and wrong, and only 11% say they look to religious leaders a lot. The shares of teens who look to religion “not much” or “not at all” when making moral decisions are particularly large relative to the other potential sources mentioned in the survey. Four-in-ten teens use little to no help from religious teachings and beliefs to make decisions about what is right and wrong, and about six-in-ten (61%) say the same about religious leaders.

Teens who are religious “nones” rely less on some sources of moral guidance than those who are affiliated with a religion. Not only are they far less likely than affiliated teens to rely a lot on religious teachings and beliefs (2% vs. 30%) or religious leaders (1% vs. 16%), but they also are not as likely to turn to parents and other family members (53% vs. 64%).

Evangelical Protestant teenagers stand out in the opposite way. In particular, they are more likely than most other Christian teens to look to religion to help decide questions of right and wrong. For instance, about four-in-ten evangelical teens (41%) rely on religious teachings and beliefs a lot when deciding what is right and wrong, compared with a quarter of Catholic teens and about one-in-five mainline Protestant teens (19%). Similarly, a quarter of evangelical Protestant teens look to religious leaders a lot when making ethical decisions, while only 13% of Catholics and about one-in-ten mainline Protestants (9%) say the same.

Evangelical Protestant teenagers stand out in the opposite way. In particular, they are more likely than most other Christian teens to look to religion to help decide questions of right and wrong. For instance, about four-in-ten evangelical teens (41%) rely on religious teachings and beliefs a lot when deciding what is right and wrong, compared with a quarter of Catholic teens and about one-in-five mainline Protestant teens (19%). Similarly, a quarter of evangelical Protestant teens look to religious leaders a lot when making ethical decisions, while only 13% of Catholics and about one-in-ten mainline Protestants (9%) say the same.

Conversely, evangelical Protestant teens are relatively unlikely to say they look to practical experience and common sense a lot when deciding what is right and wrong. Half of evangelical Protestants rely on practical experience and common sense in this way, compared with roughly six-in-ten unaffiliated (61%) and mainline Protestant (64%) teens.

In addition to religious affiliation, the importance teens place on religion is linked to how they decide between right and wrong. For example, adolescents who say religion is very important in their lives (62%) are about four times more likely than those who say religion is somewhat important in their lives (15%) to look to religious teachings and beliefs for ethical guidance. Those who say religion is very important in their lives also are more likely than others to rely on religious leaders, parents and other family members, and teachers in this way.

More teens hold a pluralistic view of religion than an exclusivist one

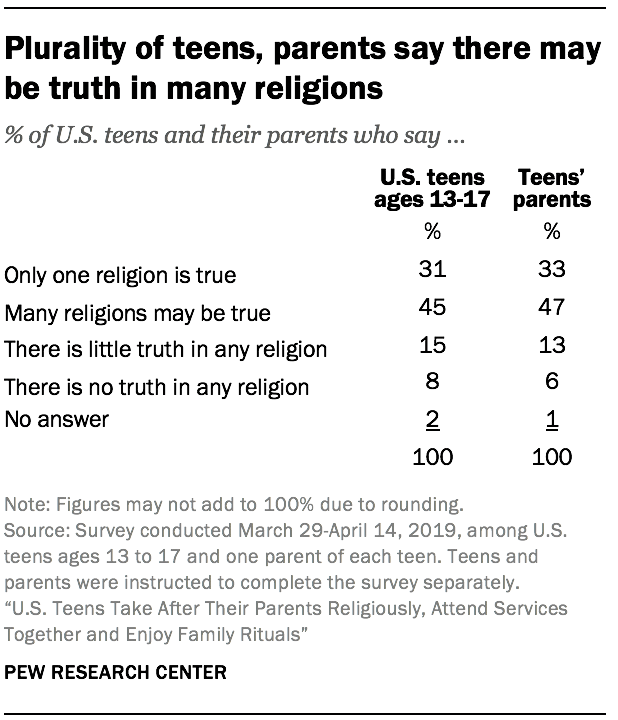

A plurality of American teenagers (45%) express the belief that many religions may be true, while 31% say that only one religion is true. Fewer say that there is little (15%) or no (8%) truth in any religion.

A plurality of American teenagers (45%) express the belief that many religions may be true, while 31% say that only one religion is true. Fewer say that there is little (15%) or no (8%) truth in any religion.

On this question, responding parents express largely similar views. Roughly half (47%) say that many religions may be true, and a third hold the view that only one religion is true.

Evangelical Protestant adolescents are more likely than other religious groups to take the exclusivist view. Two-thirds (66%) say that only one religion is true, compared with 31% of Catholics and 28% of mainline Protestants who say the same. Among U.S. adults, evangelical Protestants also are especially likely to espouse exclusivist perspectives, possibly due to that community’s emphasis on salvation that necessitates adherence to specific beliefs.21

Evangelical Protestant adolescents are more likely than other religious groups to take the exclusivist view. Two-thirds (66%) say that only one religion is true, compared with 31% of Catholics and 28% of mainline Protestants who say the same. Among U.S. adults, evangelical Protestants also are especially likely to espouse exclusivist perspectives, possibly due to that community’s emphasis on salvation that necessitates adherence to specific beliefs.21

Religious “nones” are more likely to say that many religions may be true (46%) than to give any other single response, but a similar share (47%) believe that religion holds either little (27%) or no truth (21%) when those two responses are combined.

Across most demographic groups, U.S. adolescents are more likely to express the opinion that multiple religions may be true than to say that only one religion is true. Some regional distinctions do stand out, however. Teens in the Northeast are more likely than teens in any other region to say that many religions may be true: 61% say this, compared with half or fewer among teens in the Midwest (51%), South (41%) or West (37%).