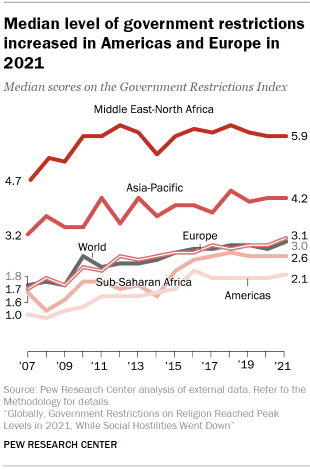

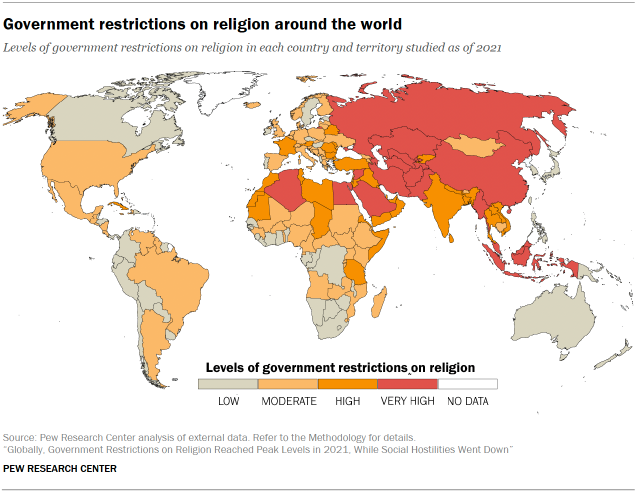

Government restrictions on religion, by region

The global median score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) rose from 2.8 in 2020 to 3.0 in 2021, the highest it’s been since Pew Research Center created the index in 2007. Both Europe and the Americas saw increases in their regional GRI scores, though their median scores remained lower than in the Asia-Pacific and Middle East-North Africa regions. Index scores remained the same from 2020 to 2021 in the Asia-Pacific, Middle East-North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa regions.

In Europe, the median GRI score ticked up from 2.9 to 3.1, while the score for the Americas rose from 2.0 to 2.1. Part of what drove these small increases, in both regions, were accusations that governments failed to intervene to prevent discrimination or abuses against religious people.

For example, in Finland, a member of an interfaith dialogue group said that verbal and physical abuse against Muslim women went unaddressed by authorities and that, as a result, many Muslims – especially women who wear hijabs – did not report harassment they faced in 2021. And Jewish community representatives in Finland said police had video and photo evidence but made no arrests of vandals who posted antisemitic posters and stickers at a synagogue, on public property and in Helsinki neighborhoods with large Jewish populations.

Harassment of religious groups remained widespread across Europe, occurring in 43 of the region’s 45 countries in 2021. In Germany, where several states already banned schoolteachers from wearing headscarves, a new federal law came into effect that allowed authorities to restrict tattoos, clothing, hair and other symbols for civil servants. Religious symbols could be restricted under this law if employers said they “adversely” affected public perceptions of how civil servants did their jobs. Furthermore, the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled in two appellate cases brought in Hamburg and Bavaria that employers could ban employees from wearing headscarves so that they would appear neutral to clients.

The Americas continued to have the lowest levels of religion-related government restrictions of any region in the study. Still, in Haiti, the media reported that police did not open cases or make arrests after multiple religious leaders and congregants were kidnapped for ransom in 2021. In one instance, after seven Catholic clergy were kidnapped by gang members, the Catholic Church stopped all church activities in the country for three days, shutting down parishes, schools, nonprofit organizations and Catholic-owned businesses to protest the lack of progress in negotiations for the hostages’ release. (The hostages eventually were released.)

In addition, government interference in worship was reported in 28 of the 35 countries in the Americas. In Colombia, where conscientious objectors have been exempt from military service under certain conditions, religious groups continued to complain about a law mandating that a commission review applications for these exemptions. The religious groups said some objectors were denied exemptions (though they did not have to carry weapons during their military service).

The Middle East-North Africa region once again had the highest median GRI score of any region analyzed (5.9). The region has held this record every year of the study so far. As in previous years, government favoritism of religion remained prevalent, with 19 of 20 countries in the region recognizing a favored religion in its constitution. Sudan is the only country in the region whose constitution did not recognize a favored religion in 2021. An interim Sudanese constitution, from 2019, does not rely on sharia as a source of law, and it has provisions for freedom of worship.6 (Sudan’s previous constitution was suspended in 2019 when the military deposed the country’s former leader.)

As in previous years, all countries in the Middle East-North Africa region reported at least one case of government harassment against religious groups in 2021, as well as at least one case of government interference in worship. In Saudi Arabia, the government continued to forbid the public practice of religions other than Islam and banned promotion of atheism. People who practiced religions other than the form of Sunni Islam favored by the government were “vulnerable to detention, discrimination, harassment, and, for noncitizens, deportation,” according to the U.S. State Department. Most countries in the region also continued to place restrictions on public preaching, proselytizing and religious conversions.

The median score on the Government Restrictions Index remained at 4.2 in the Asia-Pacific region and at 2.6 in sub-Saharan Africa. Asia and the Pacific included several countries with “very high” levels of government restrictions, including China, Afghanistan and Iran. As in previous years, China continued to restrict the activities of religious groups that were deemed a threat to the Chinese Communist Party. And since 2017, according to U.S. government estimates, more than one million Uyghur Muslims, ethnic Kazakhs, Hui and other Muslim groups, along with some Christians, were detained in internment camps in China.

In Afghanistan, the Taliban took power in August 2021 and imposed its interpretation of Islamic law with decrees that included rules for women’s clothing, men’s facial hair and gender segregation. In Iran, the parliament criminalized the act of insulting Islamic schools of thought as well as any proselytizing activity that “contradicts or interferes” with Islam, which nongovernmental organizations said made religious minorities more vulnerable to restrictions. The group United for Iran said the government either imprisoned or executed at least 62 people in 2021 on charges of “enmity against God” or “armed rebellion against Islamic rule.”

In sub-Saharan Africa, governments harassed religious groups in 44 of 48 countries and interfered in worship in 39 countries. For example, in the Central African Republic, where there has been renewed conflict along sectarian lines since late 2012, government security forces and Russian-backed mercenaries “disproportionately targeted” and “indiscriminately” killed Muslim civilians in 2021 while fighting against rebel groups, according to the U.S. State Department. A media source reported in February that pro-government forces killed 14 people at a mosque, and that military forces and the Russian-backed mercenaries “raped, tortured, and killed Muslim civilians.”

In Mozambique, in response to attacks by the Islamic State that began in 2017, government forces arbitrarily detained people who they believed to be Muslim based on appearance, according to media and Islamic organizations in the country. Nongovernmental organizations and the media said this government response “exacerbate[ed] existing grievances among historically marginalized majority-Muslim populations,” according to the U.S. State Department.

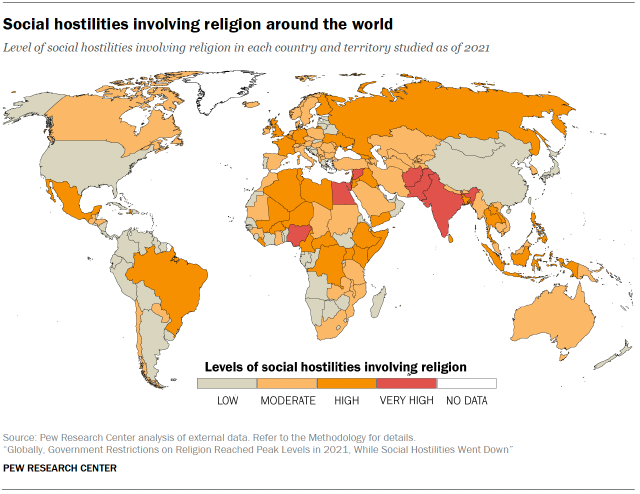

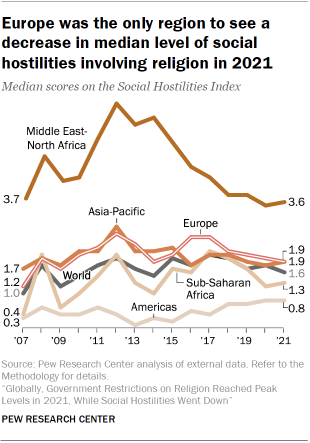

Social hostilities involving religion, by region

Worldwide, social hostilities involving religion fell slightly; the global median score on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) dropped from 1.8 in 2020 to 1.6 in 2021.7 Regionally, sub-Saharan Africa, the Asia-Pacific region, and the Middle East and North Africa saw slight increases intheir SHI index scores, while Europe experienced a decline and the median SHI score in the Americas stayed the same.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the median score ticked up from 1.2 in 2020 to 1.3 in 2021. In the Asia-Pacific region, the median score rose from 1.8 to 1.9 in 2021, while in the Middle East and North Africa, it went from 3.5 to 3.6.

Nigeria had the highest levels of social hostilities in 2021 among the countries analyzed. According to the U.S. State Department, “intercommunal clashes” – driven by competition for natural resources – occurred throughout the year between “predominantly” Christian farmers and Muslim herders, who have both formed armed groups. In August, for instance, ethnic Irigwe Christians killed 27 people and injured 14 others when they attacked five buses transporting Muslims as they traveled through Plateau State. And in September, Muslim herdsmen killed 49 people and kidnapped 27 others (most of whom were Christian) in attacks carried out in three areas in the state of Kaduna. In addition, there was continued violence by Boko Haram and Islamic State militants throughout 2021, which contributed to social hostilities in the country.

India had the second-highest level of social hostilities among the countries in the study. Although the SHI score in India declined from 2020 to 2021, the country continued to have the highest levels of social hostilities in the Asia-Pacific region, followed by Afghanistan and Pakistan. In all three countries, members of religious minorities faced violence. In India, a NGO called the United Christian Forum said the number of “violent attacks” targeting Christians increased from 279 in 2020 to 486 in 2021. Attacks on Muslim properties by Hindu nationalist groups were also reported during the year, including incidents in October targeting mosques and Muslim-owned shops and houses in Tripura state. The media reported that these attacks were in retaliation for violence against Hindu minorities in the neighboring country of Bangladesh.

In Afghanistan, attacks by the Islamic State increased, targeting the Taliban as well as Shiite minorities and other civilians. In October 2021, suicide bombers struck a Shiite mosque in Kunduz province, killing dozens of people from the Shiite Hazara community. In a separate October attack on the largest Shiite mosque in the province of Kandahar, the Islamic State killed 47 people and injured almost 70, according to the U.S. State Department.

The Shiite Hazara community was also targeted in Pakistan by the Islamic State and another armed group, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). And Pakistan experienced mob violence related to religion: In December, hundreds of Muslim workers attacked a factory manager – a Sri Lankan Christian – after he allegedly removed the posters of a far-right political party which included Islamic prayers. Accused of blasphemy, the man was beaten and stoned to death, and his corpse was set on fire. The country’s prime minister described what happened as “horrific” and ordered an investigation that led to more than 100 arrests. Other minorities such as Hindus and Ahmadi Muslims were also targeted in Pakistan throughout the year.

In the Middle East-North Africa region, Syria had the highest levels of social hostilities in 2021, followed by Israel, Egypt and the Palestinian territories. In Syria, which in 2021 entered its 10th year of conflict since uprisings began against the ruling Assad regime, armed Syrian opposition groups backed by Turkey – known as “TSOs” – targeted religious and ethnic minorities such as Yezidis in what the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom described as “acts of religious and ethnic cleansing.”

In Israel and the Palestinian territories, several attacks against clergy and religious properties were reported. For example, an escalation of hostilities in Jerusalem and Gaza led to a weeklong period of civil unrest in “mixed Jewish-Arab” cities where synagogues, a mosque and Muslim gravesites were attacked, according to the U.S. State Department. Attacks by ultra-Orthodox Jews were also reported against Christian clergy and pilgrims in Jerusalem, and against Jewish women worshiping at the Western Wall prayer site.

In Europe, the median level of social hostilities fell from 2.0 in 2020 to 1.9 in 2021, while the Americas’ score remained at 0.8 – the lowest of all the regions analyzed.