Many international studies, including from Pew Research Center, compare levels of religious identity and commitment across countries. China tends to rank high on the lists of countries with the biggest share of people who are – by several measures – secular.

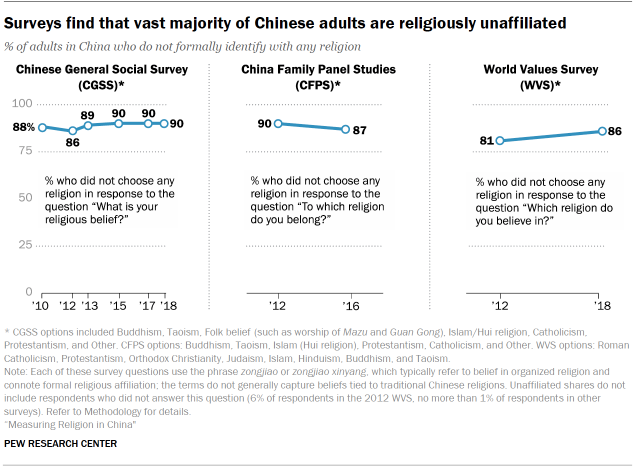

In China, religious affiliation is typically translated as “religious belief,” such as in the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) question “What is your religious belief (zongjiao xinyang 宗教信仰)?” In 2018, 90% of Chinese adults chose the option “No religious belief” in response to this question.84 By this measure, about 998 million Chinese adults were religiously unaffiliated in 2018. Other national studies, including the World Values Survey (WVS), also find that about nine-in-ten adults in China do not have a zongjiao xinyang.

However, questions that translate religion as zongjiao (宗教) capture a narrow facet of religion, as the phrase commonly connotes formal membership in a religious organization or a public commitment to a religious belief system. When respondents choose the “no religious belief” (wu zongjiao xinyang 无宗教信仰) option in a survey, they might not have in mind a complete lack of religious or spiritual beliefs. For example, they may not associate belief in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva or folk deities with the word “religion” (zongjiao).

In addition, some Chinese people may reject zongjiao affiliation because they only occasionally engage in zongjiao activities, or because they see that the state disapproves of zongjiao.

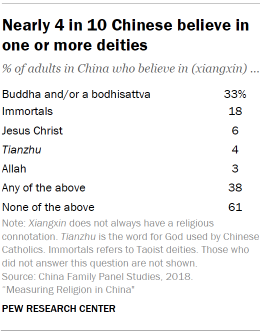

As a result, the share of people who claim to have “no religion” is far larger than the share who reject any belief in gods or who never engage in spiritual activities. For example, when asked whether they believe in (xiangxin 相信) any gods or deities, only 61% of Chinese adults said they do not believe in Buddha and/or a bodhisattva, Taoist immortals, Jesus Christ, Tianzhu (天主, the word for God used by Chinese Catholics), or Allah, according to the 2018 CFPS. (Xiangxin, which is commonly translated as “believe in,” also means to trust or have no doubts in. The term does not always connote worship or veneration.) When the analysis includes belief in supernatural forces or participation in traditional customs with spiritual underpinnings, the rate of non-religion drops even further.

And while the Chinese Communist Party espouses atheism as its official ideology, just one-third of Chinese adults identify as atheist (wu shen lun zhe 无神论者), according to the 2018 WVS.

This chapter discusses different ways of looking at non-religion in China, and it explains the advantages and limitations of using zongjiao affiliation to estimate the extent of secularism in China.

While it is an exaggeration to say that 90% of China’s population is secular, it also is an exaggeration to suggest that religious and/or spiritual practices are pervasive and frequent. Common survey measures and categories of analysis tend to ignore traditional customs and may poorly capture beliefs, which overlap and are not consistently detected when question wording and format vary. Ultimately, the best available survey data indicates that in many senses, a considerable portion of China’s population rejects supernatural beliefs and does not engage in frequent religious rituals.

China has a long history of spiritual and cultural practices that can broadly be described as religious, but the concept of “religion” is fairly new. The term zongjiao (宗教), the closest equivalent to the English word “religion,” was introduced to China in the 19th century by scholars seeking a term to use when translating Western texts.

Today, the term zongjiao often has negative connotations, and associating with zongjiao beliefs or practices is, for many, politically and socially undesirable. In state media, zongjiao is often mentioned along with extremism, violence and fraud. Zongjiao beliefs or activities are explicitly banned for Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members and cadres, who are supposed to firmly adhere to communism’s atheist ideology.

Meanwhile, the term xinyang (信仰), which literally means “firm belief in” or “commitment to” a theory, thought or philosophy, is commonly used to indicate a formal commitment or serious conviction. Surveys such as the Chinese General Social Survey use the combined phrase zongjiao xinyang (宗教信仰) to ask about religious affiliation, much in the same way the U.S. General Social Survey, for example, asks “What is your religious preference?” or Pew Research Center in the United States asks “What is your present religion, if any?”

However, stating that one does not have a zongjiao xinyang or does not engage in zongjiao activities by no means equates to completely abstaining from religion. In fact, Chinese people often engage with beliefs and practices that can be considered religious, broadly speaking, even if they do not associate with religion (zongjiao).

This seeming discrepancy can be attributed mainly to China’s distinct categorization of traditional beliefs and activities with spiritual elements or underpinnings.

For example, Chinese people typically refer to beliefs and activities of traditional Chinese religions – such as the common practice of burning incense to worship Buddha/deities (shaoxiangbaifo 烧香拜佛) – as “superstition” (mixin 迷信) or “custom” (xisu 习俗) instead of zongjiao. State-run media also describe some explicitly folk religious activities, such as the Mazu (妈祖) parade and welcoming the god of wealth, as folk “custom” rather than zongjiao, even though these activities involve making offerings and praying to deities.

Unlike Christianity and Islam, traditional Chinese religions including Buddhism, Taoism and folk religions do not emphasize membership, commitment to one god, or regular congregational involvement. Rather, some scholars have argued that religious engagement in China largely revolves around efficacy (ling 灵 or lingyan 灵验) – how well a particular deity or ritual responds to a person’s request.85 In this view, people engaging in various religious activities are “consumers” choosing among many religious rituals and sometimes mixing elements of multiple traditions.

Characteristics of those with no zongjiao affiliation

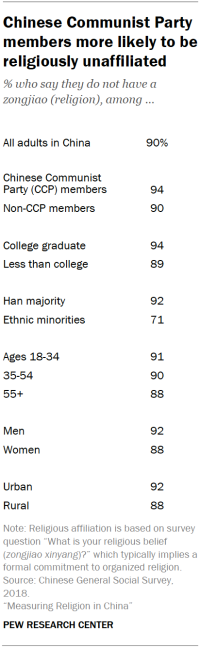

Religious non-affiliation is particularly high among members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP): 94% of this group is religiously unaffiliated, according to the 2018 CGSS. This is likely due at least in part to the Chinese government’s ban on zongjiao affiliation for its members and cadres. Religious non-affiliation is also high among Chinese adults with a college degree or more (94%). This similarity may be due to the correlation between education and CCP membership: CCP members are more likely than other Chinese to have a college degree, and nearly half of college-educated adults are members of the CCP or its Youth League, the survey shows. Refer to the sidebar called “The Chinese Communist Party’s role in China’s low levels of zongjiao religion.”

Chinese from the Han majority (92%) are more likely than people from ethnic minorities (71%) to be religiously unaffiliated, according to the 2018 CGSS.

On the other hand, older adults (ages 55 and older), women, and people living in rural areas are less likely to be religiously unaffiliated (88% each).

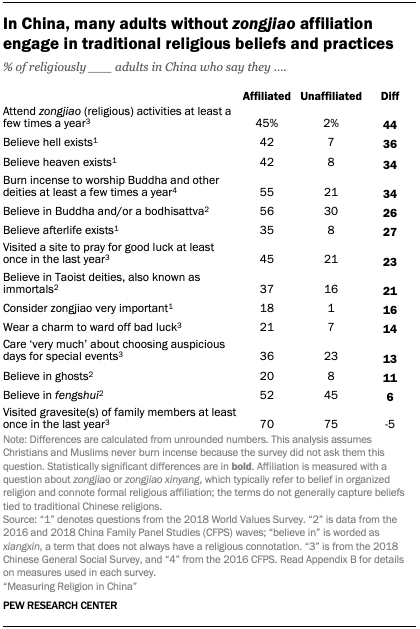

Not surprisingly, lack of zongjiao affiliation correlates with low rates of zongjiao engagement: Around 2% of unaffiliated adults participate in zongjiao religious activities at least a few times a year, compared with 45% of affiliated adults, according to the 2018 CGSS.

People without a zongjiao affiliation also are far less likely than affiliated adults to say zongjiao is very important in their lives (1% vs. 18%), according to the 2018 WVS.

The Chinese government recognizes 56 ethnic groups, including the majority Han group that makes up 91% of the population.

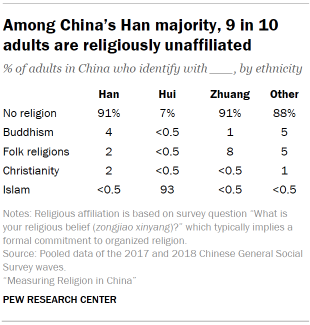

More than nine-in-ten Han adults are religiously unaffiliated, according to the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS).86 About 8% of Zhuang adults (the largest ethnic minority) identify with folk religions. Meanwhile, about nine-in-ten of the Hui and Uyghur minorities are Muslim. (Due to a lack of recent data collected in Xinjiang, this estimate for Uyghurs is from 2010 and 2012 CGSS data, and it is unclear whether Muslim identification among Uyghurs has changed since then.)

Because the CGSS does not measure each ethnic identity, it is not possible to quantify the religious composition of all minority groups. But scholars and journalists have found certain religions to be particularly prevalent among certain groups. For example, Buddhism is the dominant religion among Dai and Tibetan people. Christianity is often found among Lisus and Miaos, as is Benzhu worship among Bai people. The Dongba religion is common among Naxi people.

Engagement with traditional beliefs and practices

Nevertheless, Chinese adults without a zongjiao xinyang still engage in beliefs and practices associated with traditional Chinese religions, though often to a lesser extent than religiously affiliated adults.

Religiously unaffiliated and affiliated adults are about as likely to perform the Confucian ritual of ancestor worship, with 75% of religiously unaffiliated adults and 70% of affiliated adults saying they visited the gravesite(s) of family members at least once in the past year, according to the 2018 CGSS.

Fully 61% of religiously unaffiliated adults say they care “somewhat” or “very much” about choosing an auspicious day for special occasions, such as weddings and funerals, compared with 66% among religiously affiliated adults, the same survey shows. And 45% of unaffiliated adults say they believe in fengshui (风水), compared with 52% of affiliated adults who say this, according to the 2016 and 2018 CFPS waves.

Differences between religiously unaffiliated and affiliated adults are larger on other measures. Unaffiliated adults are far less likely to say they burn incense to pay respects to Buddha or other deities at least a few times a year (21% vs. 55%) and even less likely to do so monthly or more often (8% vs. 34%), according to the 2016 CFPS.

Unaffiliated adults are less likely than affiliated adults to say they believe in Buddha (30% vs. 56%) and Taoist deities (16% vs. 37%), according to the 2016 and 2018 CFPS waves.87

They are also less likely to say they visited a site to pray for good luck in the last year (21% vs. 45%), according to the 2018 CGSS.

Atheism among Chinese adults

Considering the Chinese government’s active promotion of atheism and communism in schools and state-run media, one might expect most Chinese adults to identify as atheist, a politically desirable label.

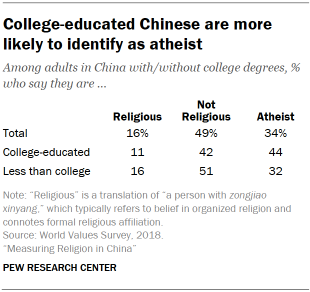

However, only about a third of adults in China (34%) say they are atheist, when asked to choose from three options in the 2018 WVS – a religious person(or a person with zongjiao xinyang), not a religious person, or an atheist (wu shen lun zhe 无神论者) – to identify themselves.88 Roughly half (49%) say they are not a religious person, while 16% say they are a religious person.

In the Chinese translation, “religious person” means a person of zongjiao xinyang. A different wording or question format might produce higher or lower estimates. For instance, it is possible that a much higher share of Chinese adults would answer “an atheist” if forced to choose between “an atheist” and “not an atheist,” as the latter may indicate that one has a zongjiao belief, which is politically undesirable.

College-educated adults are more likely to say they are atheist than those without a college degree (44% vs. 32%). The correlation between education and atheist identity is likely tied to CCP membership patterns. Roughly half of college-educated adults are members of either the CCP or its Youth League, according to the 2018 CGSS. (Refer to the discussion of the CCP’s role in promoting non-affiliation.)

Sidebar: The Chinese Communist Party’s role in China’s low levels of zongjiao religion

In line with the Marxist view that religion is a temporary phenomenon that will fade as societies advance, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) espouses and promotes atheism, thus stigmatizing belief in and engagement with religion, including zongjiao (宗教) and “superstition” (mixin 迷信). Children under 18 are constitutionally prohibited from having any religious belief (zongjiao xinyang 宗教信仰), and atheist education begins early.

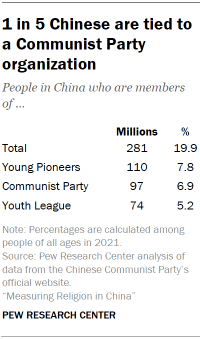

The CCP has more than 97 million adult members. An additional 30 million people are actively seeking affiliation with the CCP, including 21 million whose applications are awaiting review and 10 million who are in the advanced stages of becoming members. To join CCP-affiliated organizations, one must declare a commitment to communism, which requires renouncing any zongjiao xinyang, or formal religious affiliation. In addition, almost every primary school student pledges commitment to the communist cause in order to join the CCP’s Young Pioneers, which is considered a great honor, and large numbers of advanced students are recruited for the Youth League in middle and high school. Overall, 184 million people belong to the CCP’s Young Pioneers and Youth League.

This means that about one-fifth of China’s population has an active membership of some kind with the CCP or its youth affiliates.

The CCP bans its members and government officials, including those who are retired, from having zongjiao xinyang. In state-run media, holding zongjiao xinyang is equated with wavering loyalty to the CCP and a betrayal of communism. In speeches, President Xi Jinping and other officials stress that CCP members must be “unyielding Marxist atheists.”

CCP membership brings career opportunities and benefits, while zongjiao xinyang may invite scrutiny and even disadvantage. The popular national civil service exam, where applicants compete for “golden rice bowl” positions, is an example. Even though applicants, regardless of political or religious background, are in theory guaranteed equal treatment, CCP members are known to have better chances of securing a position than non-members. By contrast, eligible candidates who have participated in superstitious or zongjiao activities risk failing the political background check.

There are also reported instances of Chinese people losing jobs due to their zongjiao xinyang, and of college students being pressured to renounce their faith. The prospect of such complications may discourage people from participating in zongjiao activities or disclosing their zongjiao xinyang, if they have any, on surveys.

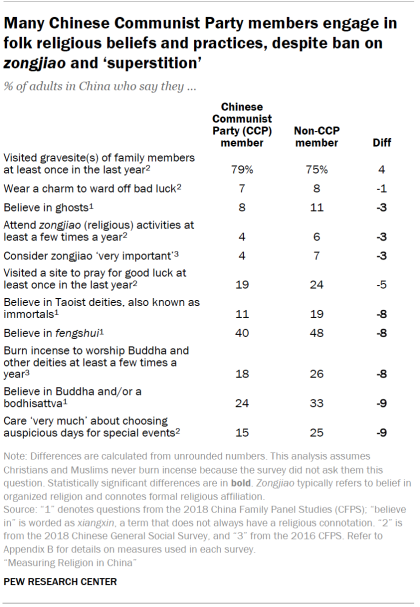

While the CCP imposes a strict ban on zongjiao activities among officials and CCP members, it tolerates occasional or infrequent engagement in some traditional Chinese religious practices. For example, visiting temples occasionally is not an indicator of involvement in zongjiao or “superstitious” (mixin) activities, according to the CCP’s instructions. CCP members are also allowed to participate in folk activities with religious elements.

However, any CCP members who actively practice superstition – such as carrying many amulets and frequently consulting fortunetellers – face expulsion.

Likewise, while the CCP’s campaigns in favor of atheism may have been effective in discouraging people from engaging in zongjiao or superstitious beliefs and practices, they have not been completely successful.

In fact, a considerable share of CCP members express beliefs in fengshui (40%), Buddha and/or a bodhisattva (24%), and Taoist immortals (11%), though those rates are lower than among non-CCP members, according to the 2018 CGSS and other surveys.

Moreover, CCP members are no different from the rest of the adult population in their propensity to engage in customary activities that may not be overtly zongjiao or “superstitious,” such as carrying a lucky charm or amulet, visiting a religious site to pray for good fortune, or visiting the gravesite(s) of family members.