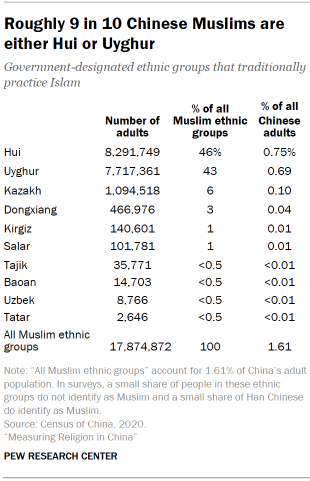

The vast majority of Chinese Muslim adults come from 10 ethnic minority groups that traditionally practice Islam, the two largest being the Hui people and the Uyghur people. Most of China’s Muslims live in the country’s northwestern region, particularly in the areas of Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia and Xinjiang.

Because there is heavy overlap between religion and ethnicity among these minority groups, there is less uncertainty about the size of China’s Muslim population than there is about some of its other religious groups, such as Buddhists and Christians.

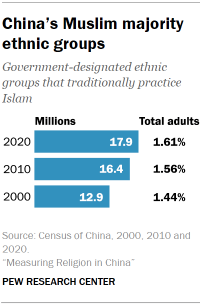

Chinese authorities and international scholars generally estimate there are 18 million Muslim adults in China. Pew Research Center’s estimate is in the same ballpark but slightly lower, at about 17 million, for reasons discussed below.

Notwithstanding the relative consensus around Muslim population numbers, studying Islam in China comes with many challenges. To begin with, the Chinese government has been accused by international organizations of human rights abuses and genocide against Uyghurs and other Muslims. Some Chinese Muslim scholars have reportedly been detained, while some foreigners who study Islam in China have been barred from traveling to the country.

In this climate, Chinese Muslims may hesitate to discuss their religious identity, beliefs or practices with survey researchers, and some may have moved away (or been pushed away) from their traditional religion. Compounding the uncertainty, the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), a key source of data, has not been conducted in Xinjiang – home to nearly all Uyghurs in China – since 2013.

(Read more discussion of the challenges of studying Muslims in China and a summary of media coverage on Xinjiang.)

Islam was brought to China in the seventh century by Arab and Persian merchants who settled in port cities on China’s southeastern coast. But it wasn’t until the Mongol conquest in the 13th century, and the subsequent arrival of more permanent settlers from Central Asia, that Islam began to spread inland.

These Muslim minorities eventually became known, collectively, as the Hui people. The Hui came to include Muslims of Arab and Persian origin as well as Tibetans and Han Chinese who converted to Islam and even some non-Muslims, such as Chinese Jews, known as “Blue-hat Huis.”79 As the Chinese empire grew, it gained new ethnic minorities from adjacent regions who had converted to Islam in prior centuries. The largest of these is today’s Uyghur people, who originated as Turkic nomads in the Central Asian Altai mountains, in the northern tip of modern-day Xinjiang bordering Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Russia.

Since the Chinese Communist Revolution of 1949, authorities have variously encouraged, tolerated and suppressed self-rule and cultural expression among Uyghurs, Huis and other ethnic minorities. Beginning in the 1950s, the Chinese government created “ethnic autonomous regions” (such as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region) to make it easier for ethnic minorities to preserve their traditions. But during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), religious activities were prohibited for all Chinese, regardless of ethnic background.

In recent years, Muslims in Xinjiang – including Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities, such Kazakhs and Uzbeks – have been harshly persecuted. The U.S. government has called the treatment of Uyghur Muslims a genocide, an accusation the Chinese government has repeatedly rejected.

How many Muslims are there in China?

Pew Research Center’s estimate of the number of Chinese Muslims differs from those typically cited by the Chinese government.

China’s 10 traditionally Muslim ethnic groups are among 56 ethnicities measured in the Chinese census. Official estimates of the size of China’s Muslim population – including those generated by the Islamic Association of China, the government agency that oversees Islamic affairs – typically add up the total populations of the traditionally Muslim ethnic groups, assuming that every member of those 10 groups, without exception, is Muslim, and that there are absolutely no Muslims among the Han majority.

By this method of estimation, there were roughly 18 million Muslim adults in China in 2020, accounting for 1.6% of China’s adult population. The two largest of the sub-groups were Hui (8.3 million adults), followed by Uyghurs (7.7 million adults).80

However, there are limitations to using ethnicity as a proxy for Muslim identity.

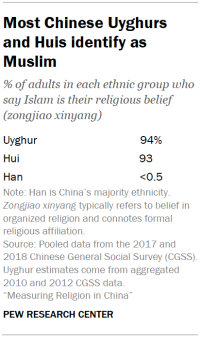

First, this approach assumes that all members of predominantly Muslim ethnic groups identify as Muslim, which surveys indicate is not the case. For example, 7% of Hui adults do not identify as Muslim, according to data from the 2017 and 2018 CGSS. Likewise, older survey data indicates that about 6% of Uyghurs did not identify as Muslim, as of about 2012.81 (Since then, there has been no survey with a sufficient sample size to analyze Muslim identification among Uyghurs.)

Second, the conventional estimation approach fails to account for Muslim converts of other ethnicities, especially those from the Han majority. Although Han Muslims are rare – only about one in every 1,500 Han adults say their religious belief (zongjiao xinyang 宗教信仰) is Islam, according to surveys – they still could add up to substantial numbers, given that there are 1.02 billion Han adults in China.

To correct for these issues, Pew Research Center demographers estimate that roughly 90% of people in China’s 10 Muslim-majority ethnic groups identify as Muslims and that roughly 700,000 Han Chinese identify with Islam, yielding a total estimate of about 17 million Muslims in China, or around 2% of the adult population. By contrast, the Islamic Association of China’s method – adding up the entire populations of the 10 Muslim-majority ethnic groups and assuming that no one in the Han majority is Muslim – yields an estimate that is higher by nearly 1 million adults.

(Read the Methodology for more details on estimating the number of Muslims in China.)

Demographic traits

Most Uyghur and Hui people belong to the Sunni branch of Islam, but they differ in other ways.

Culturally, Hui people, who began a period of rapid assimilation into the mainstream Han Chinese culture during 14th century, have a good deal in common with the Han majority, including the Han Chinese language and surnames. By contrast, Uyghurs – who until the last century had limited interactions with the Han Chinese – mainly speak Uyghur, a Turkic language. They also differ in appearance and culture from the Han majority.

In addition, Hui and Uyghur people differ on several sociodemographic measures. Uyghurs, on average, are less likely to live in cities and have fewer years of education than the Hui, who are similar to the Han majority on these measures. About 17% of Uyghur people have an urban household registration, or urban hukou (户口), compared with around 40% of Hui and Han people, according to the 2020 Chinese census. Around 5% of Uyghur adults (ages 18 and older) have a college degree or more education, while roughly 10% of Hui and Han adults are college educated.

Fertility

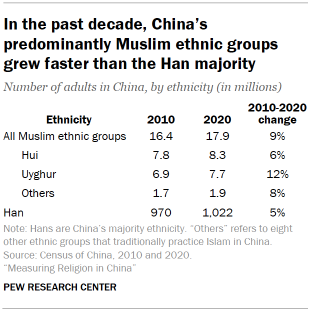

In the past decade, predominantly Muslim ethnic groups have grown more quickly than the majority Han population.

Between the 2010 and 2020 censuses, the number of adults in predominantly Muslim ethnic groups grew by 9% to 17.9 million, while the Han majority grew 5% to 1.02 billion.

This disparity may have resulted, at least in part, from the Chinese government’s less stringent controls on family size for minorities under the one-child policy, which was in effect from 1980 to 2016. While Han Chinese were restricted to having one child per family (or two, if they met certain conditions), ethnic minorities were allowed to have as many as three children per family.

The relatively young age structure of the Muslim population also fuels population growth: 27% of people in China’s predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities are younger than 15, compared with 17% of the ethnic Han majority, according to the 2020 Chinese census.

Also, according to Chinese censuses, the total fertility rate among Uyghur women was 1.84 children per woman in 2010 and 1.99 in 2000, substantially higher than the rate among both Hui women (1.42 in 2010 and 1.53 in 2000) and Han women (1.15 in 2010 and 1.18 in 2000).82 Fertility rates by ethnicity from the 2020 census were not available when this report was written.

In recent years, however, there have been reports of forced birth control methods imposed on Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic groups in Xinjiang, including mandatory pregnancy checks and sterilizations, as well as coercive IUD implantations and abortions. Scholars expect that Uyghur growth rates will slow as a result of such measures, while the rate among Han Chinese may rise after the Chinese government relaxed restrictions on family sizes, first in 2016 and again in 2021.

Beliefs and practices among Hui Muslims

Since Muslims are a small share of China’s population and surveys often omit regions with large Muslim populations, data on the beliefs and practices of Chinese Muslims is sparse. For example, the CGSS has a sufficient number of respondents to reliably report on the beliefs and practices only of Hui Muslims.83

In this section, we analyze 2018 CGSS figures on self-identified Hui Muslims and compare them with Chinese adults who formally identify with folk religion, Buddhism or Christianity. Because this analysis relies on respondents who chose a zongjiao xinyang in the CGSS survey – or who said a parent or spouse has a zongjiao xinyang – it excludes those who may engage with one of these religions but do not formally affiliate with it.

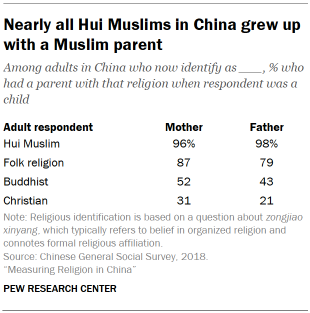

According to this analysis, Hui Muslims are the most likely of China’s major religious groups to grow up with at least one parent who shares their religion.

Among all Hui respondents who claim Islam as their zongjiao xinyang, nearly all (96%) grew up with a Muslim mother, much higher than the rate among adults who identify with Buddhism (52%) and self-identified Christians (31%), according to the 2018 CGSS.

This high level of religious similarity among Muslims also reflects the fact that Islam in China rarely draws converts from other religions. Likewise, the low level of similarity between Christians and their parent(s)’ religion during childhood suggests that most of China’s self-identified Christians come from non-Christian backgrounds.

Survey data indicates that Muslims are also the most likely of China’s major religious groups to marry within their religion. Most Hui Muslim adults (96%) share the same faith as their spouse or cohabitating partner. The comparable figures are substantially lower among adults who identify with folk religion (78%), Buddhism (45%) and Christianity (38%), according to the 2018 CGSS.

Recent change in religious activity

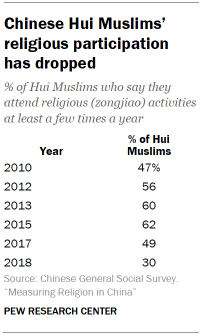

In each of the five CGSS waves between 2010 and 2017, roughly half or more of Muslim respondents (47% to 62%) said they attend zongjiao activities at least a few times a year. In 2018, only 30% said so. This could reflect a change in the way Chinese Muslims answer survey questions in the face of increasingly restrictive government policies, or a change in actual behavior, or some of both.

For comparison, in 2018, 73% of Chinese Christians said they participated in zongjiao activities at least a few times a year, as did 51% of adherents of folk religions and 36% of Buddhists. None of these groups registered a significant decline in self-reported zongjiao participation between 2010 and 2018.

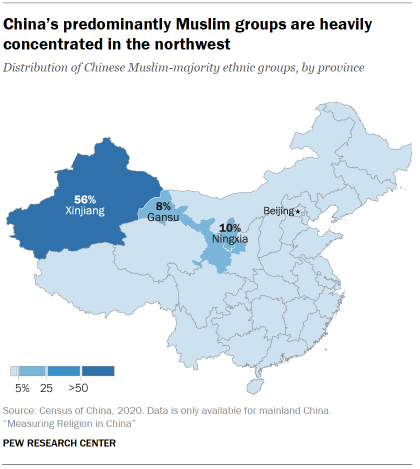

Geographic distribution of Muslims in China

Nearly all of China’s Uyghurs (99%) live in one province, Xinjiang. Hui people are more widely dispersed, with an estimated 10% in Xinjiang and 42% in the other northwestern provinces of Gansu, Ningxia and Qinghai. The remaining half are scattered across the country, with a significant concentration in Henan (8%) and Yunnan (6%).

The remaining eight predominantly Muslim ethnic groups, which make up roughly 10% of China’s Muslim-majority groups – Baoan, Dongxiang, Kazakh, Kirgiz, Salar, Tajik, Tatar and Uzbek peoples – mostly reside in the northwestern provinces of Xinjiang, Gansu and Qinghai. There is a particularly heavy concentration of Kazakh, Kirgiz, Tajik, Tatar and Uzbek people in Xinjiang.

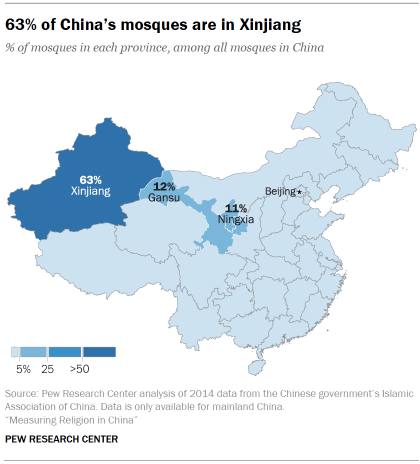

As of 2014, Xinjiang was home to 63% of China’s mosques – about 24,500 of a nationwide total of 39,000 mosques, according to data from the Islamic Association of China. About one-quarter of China’s mosques were in other northwestern provinces – Gansu (12%), Ningxia (11%) and Qinghai (3%) – while the remaining 11% of mosques were in other parts of the country.

Challenges of studying Islam in China

Studying Muslims in China is difficult for several reasons. The vast majority reside in the northwestern provinces of Xinjiang and Ningxia – mountainous, sparsely populated areas that are often excluded in national surveys for practical reasons. And even when Muslims are surveyed, the samples generally are too small to allow separate analysis and reporting of subgroups, such as by age cohort or gender.

Moreover, the CGSS has not been conducted in Xinjiang since 2013, which leaves no way to assess the current religious beliefs and practices of Uyghur adults in Xinjiang – an estimated 43% of all adults in China’s Muslim-majority ethnic groups.

The Chinese government’s treatment of Muslims adds to the challenges. Muslims who are surveyed may be guarded in their responses, while scholars who study Muslims have faced personal hardship.

For example, IIham Tohti, a Beijing-based economist and Uyghur who criticized Chinese government policies in Xinjiang, was found guilty of “separatism” in 2014 and is serving a life sentence in prison. Rahile Dawut, a professor of Uyghur traditions at Xinjiang University, disappeared ahead of a trip to Beijing in 2017 and has not been heard from since, according to reports in The New York Times and other media.

U.S. scholars have claimed they were banned from traveling to China in connection with their work on Uyghurs. German anthropologist Adrian Zenz, whose online investigations have uncovered extensive visual evidence of conditions in Xinjiang, was sued in 2021 by Chinese companies for his work, which the Chinese Foreign Ministry described as “malicious smearing acts,” The Washington Post reported.

(For more on these topics, read the sidebar called “Human rights abuses in China’s Xinjiang region” and our 2022 analysis of global government restrictions on religion.)

Discussions of Muslims’ views and demographic characteristics in this report are based on the CGSS, which is the only nationally representative survey with sufficient sample sizes to allow such an analysis, though the CGSS has not been conducted in Xinjiang since 2013 and CGSS data collected outside of Xinjiang includes few Uyghur respondents.

The number of Hui Muslims in the CGSS is large enough for analysis, but Hui respondents in the CGSS are so geographically concentrated that their survey estimates have large margins of sampling error on some measures. For instance, the share of Hui Muslim adults who attend religious activities once a week or more (11%) in the 2018 CGSS has a margin of error of plus or minus 8 percentage points, compared with 6 points for Christians and 2 points for Buddhists.

Sampling coverage issues in the CGSS also pose challenges to estimating the number of Muslims in China. Overall, predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities, particularly Huis, are oversampled in the CGSS even though some regions with large minority populations have been omitted in recent waves. The CGSS includes a larger share of Muslim ethnic minorities than China’s census and the default CGSS weight does not correct for this imbalance. To address this issue, Center researchers adjusted the weight in the CGSS so that the share of adults in predominantly Muslim ethnic groups matches the share of those ethnic groups in the census. (Read the Methodology for more on how we estimate the number of Muslims in China.)

Sidebar: Human rights abuses in China’s Xinjiang region

The Chinese government’s actions against Uyghur Muslims in the northwestern region of Xinjiang have drawn international attention and censure in recent years.

Human rights groups have accused China of subjecting hundreds of thousands of Muslims to mass internment, surveillance and torture. There have been reports of forced abortions and sterilizations, forced organ harvesting, forced relocation and labor, and forced separation of children. Amnesty International has said that China’s “draconian repression of Muslims in Xinjiang amounts to crimes against humanity,” and the U.S. State Department has described China’s treatment of Uyghurs as genocide. In 2022, the UN High Commissioner of Human Rights issued a report saying that “serious human rights violations have been committed” in Xinjiang and that “the extent of arbitrary and discriminatory detention of members of Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim groups … may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.”

The Chinese government has denied these allegations. In July 2022, China reportedly tried to stop the release of a UN report detailing abuses against Muslims. Chinese officials have said camps in Xinjiang are for vocational education and training and are meant to counter religious extremism and poverty in the region.

Accusations of repression of Uyghurs and other Muslims by the Chinese government date back many years. In 2005, Human Rights Watch described the “systematic repression of religion … in Xinjiang as a matter of considered state policy,” at a “level of punitive control seemingly designed to entirely refashion Uighur religious identity to the state’s purposes.”

However, human rights groups say the crackdown intensified after the 2009 riots in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which left nearly 200 people dead. The Chinese government labeled the riots as terrorism arising from Islamic extremism and expanded regulation and surveillance in the name of de-extremization.

Many religious practices among Uyghurs and other Muslim-majority ethnic groups in Xinjiang that previously were respected as ethnic customs now face tight regulation. For instance, the government has banned face coverings in public; made it illegal for parents to let children attend religious activities or religious schools; cracked down on “underground” Muslim schools and study groups; and increased penalties on Muslims who follow traditional Islamic marriage and divorce laws. The Chinese government also has intensified the enforcement of restrictions on the number of children allowed for Uyghur Muslims and severely punished those who exceed the limit.

For decades in the 1970s, ’80s, ’90s and 2000s, the government imposed a “one-child policy” that limited births among Han Chinese, a policy that was often realized with forced contraceptives, sterilization and abortions. During this period, urban Uyghur couples were allowed to have two children and rural Uyghur couples could have three children. In 2016, the Chinese government relaxed the one-child cap for most of the population while enforcing birth controls for minorities. In 2021, the policy was again adjusted to allow up to three children per couple, but with no exceptions for ethnic minorities.

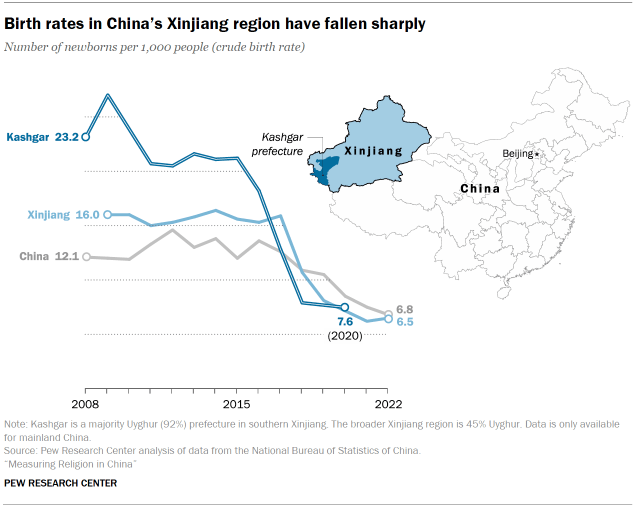

Xinjiang’s birthrate has fallen significantly in recent years: In 2019, the region’s crude birth rate – the number of births per 1,000 people – hovered below the national average (10.5) for the first time, at 8.1, nearly half the rate three years earlier, according to the National Bureau of Statistics of China.

The decline in the birth rate is particularly pronounced in southern Xinjiang, which has a heavier concentration of ethnic minorities. For instance, between 2016 and 2018, the crude birth rate in Kashgar, a 92% Uyghur prefecture, dropped in half from 18.2 births to 7.9 per 1,000 people. These large changes in fertility patterns coincide with government interventions, which may have been designed to reduce growth in ethnically Muslim populations in Xinjiang.

Moreover, the strict prohibition on providing formal religious education to children may disrupt the intergenerational transmission of religious beliefs and practices among Muslim-majority ethnic minorities in Xinjiang and other parts of China.