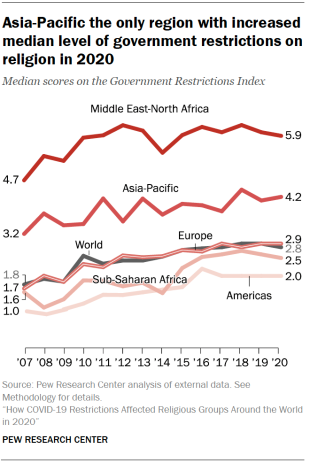

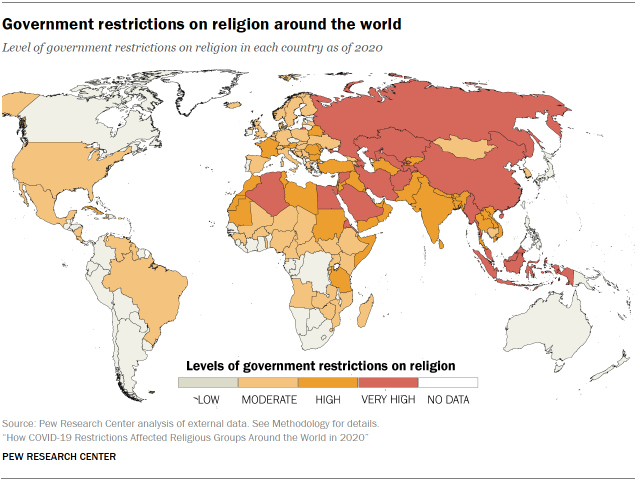

Government restrictions on religion, by region

Globally, the median score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) fell from 2.9 in 2019, which was a peak level for the study, to 2.8 in 2020. Regionally, the median GRI score declined slightly in the Middle East-North Africa, remained constant in the Americas, Europe and sub-Saharan Africa, and increased in the Asia-Pacific region.

The median score in the Middle East and North Africa fell slightly from 6.0 to 5.9, the second straight year it has fallen. Still, this region has the highest levels of government restrictions of any of the five geographic regions in the study. In every country in the region, there were reports of governments harassing religious groups and interfering in worship in 2020. In Bahrain, for instance, the government continued to target and detain Shiite clerics and individuals. In September, authorities detained several clerics for “spreading sectarianism” and defaming religious figures in their sermons and sentenced two of them to prison. Activists in the country said the sermons were part of the Shiite ritual observance of Ashura.

The vast majority of countries in the Middle East-North Africa region also imposed limits on proselytizing, converting and public preaching. In Algeria, for example, Islamic religious services were permitted only in state-sanctioned mosques led by government-authorized imams, and Friday prayers were limited to a smaller selection of mosques. It was also a criminal offense for non-Muslims to proselytize to Muslims in the country.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where the median government restrictions score remained at 2.6 in 2020, harassment and intimidation – including derogatory statements, physical violence and prohibitions on religious practices and rituals – were reported in 44 of the 48 countries in the region (92%). In Nigeria, some Muslim and Christian groups contended that state laws discriminated against them. For example, the Anglican Church said that new mandates for burial rituals in Anambra state violated religious freedom provisions of the constitution and were enacted without input from the church. And in Tanzania, some religious leaders reported they were pressured to support the country’s president, or that they faced government penalties if their public statements were deemed overly political. The Tanzanian government threatened to deregister their religious organizations and in some cases questioned their citizenship and confiscated their passports, according to the U.S. State Department.

The GRI score in the Americas stayed steady at 2.0 (the lowest level of all five regions), and in Europe it remained at 2.9. In the Americas, the vast majority of countries had “low” or “moderate” levels of government restrictions, with the exception of Cuba, which fell into the “high” category. In Cuba, the government denied registration to some Apostolic groups and did not respond to pending applications for Jehovah’s Witnesses or The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Religious groups also reported that the government used threats and other methods of coercion to limit their activities and that a new constitution in effect since February 2019 weakened religious freedom protections in the country.

In Europe, 20 out of the 45 countries in the region imposed restrictions on wearing religious symbols or clothing. In several countries – including Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands and Norway – there were bans on wearing face coverings in public, which affected Muslim women who wear veils for religious reasons.4 (Violators were threatened with fines.)

In the Asia-Pacific region, the median GRI score ticked up from 4.1 in 2019 to 4.2 in 2020. The region includes countries with some of the highest government restrictions scores, including China, Malaysia and Iran. In China, the government continued to target Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang province. International organizations such as Human Rights Watch contended that about half a million people had been imprisoned in the Chinese government’s operations on Xinjiang through the end of 2020 and that over 48,000 were prosecuted that year. The U.S. State Department, in its 2020 International Religious Freedom report on China, said that thousands of adults from the region had been transferred from Xinjiang to other parts of the country to work as laborers, and that children had been separated from their families and sent to boarding schools or orphanages to study ethnic Han culture, Mandarin and Communist Party ideology. Also, there were reported sexual assaults resulting from a program in which authorities had Han Chinese live in the homes of Uyghur families to monitor their religious observances and look for signs of “extremism” such as praying and owning religious texts, according to the State Department.

In Malaysia, which had “very high” government restrictions in 2020, minority non-Sunni groups such as Shiites and Ahmadis are considered “deviant” by the government and face various limitations on religious practices and assembly. For example, although Ahmadi Muslims reported being able to have their own worship centers, they could not hold Friday prayers because those prayers had to be conducted in officially registered mosques. Furthermore, a High Court case to determine whether Ahmadis could legally identify as Muslims remained unresolved at the end of 2020. The Malaysian government also banned books promoting Shiite beliefs, mysticism and other ideas that “deviated from the true teachings of Islam.” (In February, however, the country’s Court of Appeals overturned bans on three books.)

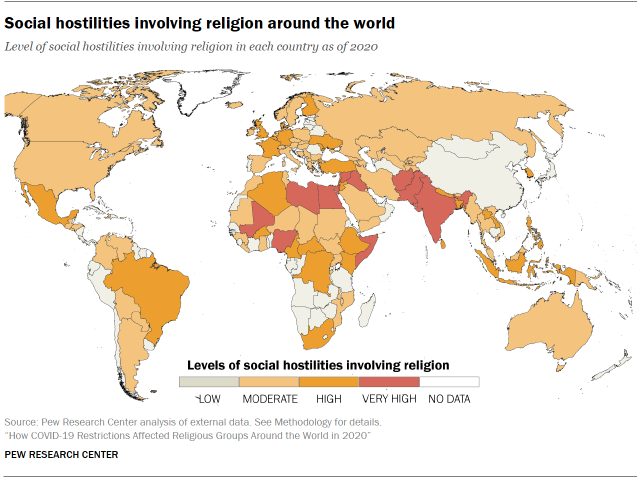

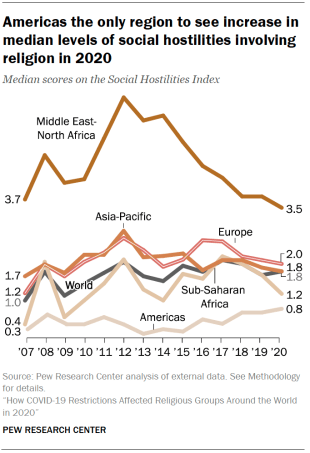

Social hostilities involving religion, by region

Globally, the median score on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) increased very slightly from 1.7 in 2019 to 1.8 in 2020.5 But the median score decreased in every major region except the Americas, where it moved up slightly. (Declines can occur when a country has fewer reports of incidents of social hostilities involving religion than it did in the previous year.)

In the Middle East-North Africa region, the median score fell from 3.8 to 3.5, and in sub-Saharan Africa it fell from 1.7 to 1.2. Asia-Pacific and Europe registered smaller declines. At the same time, some countries that already had “very high” social hostilities saw small increases in their scores. For example, India’s SHI score rose due in part to increased violence around protests of the Citizenship Amendment Act (a 2019 law that excludes Muslims from expedited citizenship offered to non-Muslim migrants). And in Israel, tensions between ultra-Orthodox Jews and secular Israelis reportedly increased because some ultra-Orthodox groups largely disregarded COVID-19 public safety restrictions and had high rates of infection in their communities. For more details on changes in SHI scores in 2020, see Chapter 1.

In the Americas, the median score ticked up from 0.7 to 0.8 but remained the lowest of any region. While most countries in the Americas had “low” or “moderate” levels of social hostilities, Mexico and Brazil fell into the “high” category. In Mexico, two evangelical Protestant pastors were killed in 2020, and there were reports that others were attacked or abducted. Nongovernmental organizations said that religious leaders were “singled out” by criminal groups for denouncing illegal activities and to instill fear so these activities could continue.