The first half of this chapter provides details on the assumptions and results of each of the four main scenarios. These are not predictions for the future. Rather, projections show what would happen under a number of hypothetical scenarios.

Some scenarios are intentionally implausible and meant only to illustrate the impact of different demographic forces. Scenario 1 is conservative, because it assumes that disaffiliation will not speed up beyond the current rate, even though in recent decades each generation of people raised Christian has disaffiliated more than the generation before it. Scenarios 2 and 3 may be more realistic because they assume that switching will continue to accelerate. Scenario 4 is implausible because it imagines that all switching ended in 2020; it is nevertheless revealing because it demonstrates how demographic dynamics (such as the higher average age of Christians) would cause the Christian share of the population to continue to decline even without any further switching.

Though some scenarios are more plausible than others, the future is uncertain, and it is possible for the religious composition of the United States in 2070 to fall outside the ranges projected.

The second half of this chapter presents four additional projections (Scenarios 5-8), to demonstrate the effects of factors other than switching. These projections show how the U.S. religious landscape might change if current switching patterns among young adults held steady, but with religious transmission set to 100%, no fertility differences by religion, no switching after age 30, or no migration.

None of the scenarios project growth in the Christian share of the U.S. population because we do not have empirical measures of any recent switching patterns that favor Christianity in the United States. In other words, there is no data on which to model a sudden or gradual revival of Christianity (or of religion in general) in the U.S. That does not mean a religious revival is impossible. It means there is no demographic basis on which to project one.13

Baseline assumptions

All the scenarios in this report start with a 2020 data baseline. Estimates of U.S. migration, fertility, age and sex structure, and mortality patterns are based on the United Nations’ demographic estimates. Religious differentials in fertility are from the National Survey of Family Growth. Baseline religious composition data comes from Pew Research Center surveys. (For a full list of sources and explanations on how baseline data was prepared for analysis, see Methodology.)

Pew Research Center estimates that in 2020, Christians made up 64% of the U.S. population (including children) while “nones” accounted for 30% and other religious groups 6%. Based on observed data, the baseline scenario assumes that 34% of people who grew up Christian will discard their religion by the time they turn 30 (including 3% who switch to a non-Christian religion and 31% who identify with no religion) and among some older cohorts of Christians, 7% will leave at a later age.14 Meanwhile, 21% of people who were raised religiously unaffiliated will become Christian by the time they reach 30.

Each scenario assigns different future switching rates to young people (ages 15 to 29) but holds switching rates steady for the small share of older adults who switch after turning 30. (This later-adulthood switching applies only to cohorts born before 1990; disaffiliation has become so common in subsequent decades that the models assume that people born after 1990 who will switch already have done so by age 30.15)

All four main scenarios assume that transmission of religion from mothers to children continues at recent rates, migration remains constant, religious differences in fertility stay stable, and there are no mortality differences among religious groups. Switching among people raised in non-Christian religions is assumed to hold steady under all but the “no switching” scenario, because there is not enough data on people in the “other religions” category to model shifting retention rates across age cohorts.

Readers familiar with Pew Research Center’s 2015 global projections might note that the 2020 U.S. religious landscape described in this report differs markedly from what was projected seven years ago. In fact, the present religious landscape is similar to the 2015 projection for 2050, with Christians representing about two-thirds of the population and the religiously unaffiliated making up more than a quarter. The 2015 global projections assumed stability in switching patterns in each country and did not anticipate an acceleration in the U.S. switching rate. The pace of disaffiliation in the U.S. increased continuously between 2010 and 2020. The “steady switching” projection scenario in this report is most similar to the assumptions modeled in the earlier projections. Other scenarios in this report attempt to capture what would happen if U.S. religious switching continues to speed up.

In our 2015 global projections report, it would have been impractical to present customized scenarios that might be appropriate for individual countries (or regions), such as the additional U.S. switching scenarios included in this report. For the sake of feasibility and comparability, a steady switching assumption was applied to every country for which switching data was available, even though steady switching was not the likeliest path for all countries. At the time, we recognized that this approach was likely conservative for projecting the growth of “nones” in the United States. In this new report, we delve into the complex switching dynamics in the U.S. with greater specificity.

Updates to projections are appropriate when facts on the ground change. For example, soon after our 2015 global projections report was released, a large wave of asylum seekers came to Europe, resulting in a rapid increase in the region’s Muslim population that had not been anticipated in our models. In 2017, we updated our European projections in a report exploring how Europe’s Muslim population could continue growing under a variety of new migration scenarios.

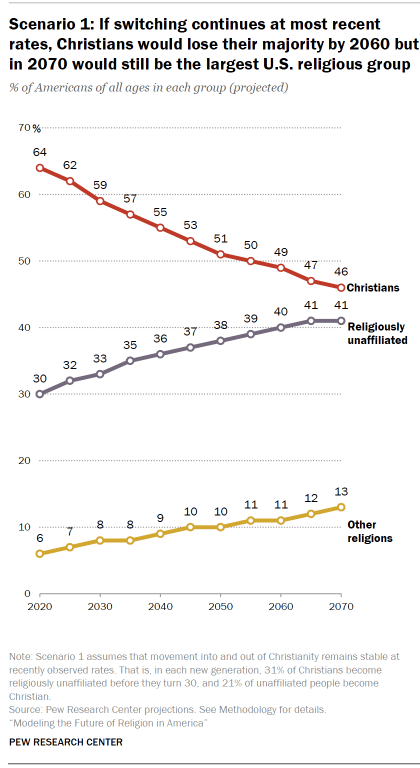

Scenario 1: Steady switching

The first scenario differs from the others in that it assumes religious switching will continue at recent rates across all age groups. That is, in each new generation, 31% of people who were raised Christian become religiously unaffiliated between the ages of 15 and 29, while 21% of those who grew up with no religion become Christian. Moreover, 7% of people who were raised Christian disaffiliate between the ages of 30 and 65.16

Other demographic forces that can affect religious composition – migration patterns, differences in religious groups’ birth rates, and the rate at which parents transmit religious identity to their children – are held steady. (These factors remain constant in each of the four main scenarios, but not in Scenarios 5-8, which begin later in this chapter.)

In these circumstances, the largest amount of change among Christians and the religiously unaffiliated would occur by 2050. Christians would decline as a share of the population by a few percentage points per decade, dipping below 50% by 2060. In 2070, 46% of Americans would identify as Christian, making Christians a plurality – the most common religious identity – but no longer a majority. In this scenario, the share of “nones” would reach 41%, and other groups would make up the remaining 13%.

(Scenario outcomes for non-Christian religions are closer than they may appear due to rounding. For example, people of other religions are projected to make up 12.53% of the U.S. population in 2070 under Scenario 1 and 12.48% under Scenario 2.)

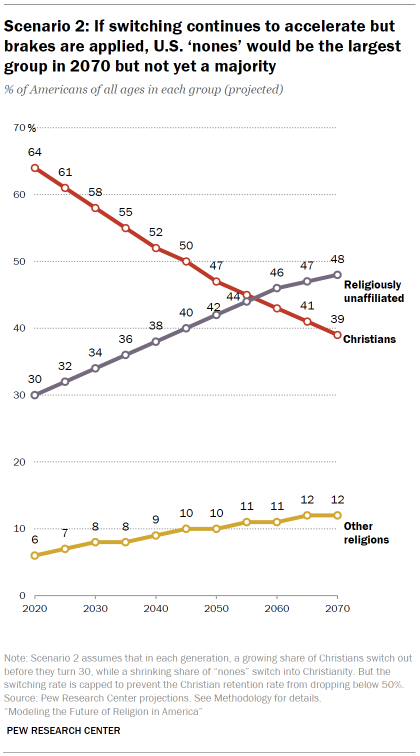

Scenario 2: Rising disaffiliation with limits

In this scenario, leaving Christianity is assumed to become more common across each successive cohort of young adults, continuing recent trends. However, this scenario also assumes that Christian retention – that is, the share of people who were raised Christian and still identify as Christian after young adulthood – can only go as low as 50% for men and 55% for women.

This artificial “floor” is roughly equal to the lowest retention rate observed in an analysis of 79 other countries. Great Britain has a Christian retention rate of 49%, the lowest in this analysis, followed by France at 52%. The “limits” in this scenario only assume there may be a cap on how rapidly change can take place within a generation for people raised Christian or raised with no religion. No predetermined limit is imposed on the eventual size of populations of Christians, the religiously unaffiliated or of all other religions.

The scenario also assumes that at least 5% of people raised without a religion will convert into one, either to Christianity or another faith. Having no religious affiliation is very quickly becoming “stickier,” but this assumption recognizes that retention among the unaffiliated is unlikely ever to reach 100%.

With these assumptions, the trend in which each cohort of young adults disaffiliates from Christianity at higher rates than the preceding cohort continues and reaches an imposed “floor” retention rate of 53% overall (50% for men and 55% for women) in 2050, among the cohort born between 2016 and 2020.

Under these conditions, people who do not identify with any religion would become the largest group around the year 2060, though they would not represent a majority of Americans. By 2070, “nones” would be a plurality of 48%, Christians would account for 39% of the U.S. population, and 12% of Americans would belong to other religions.

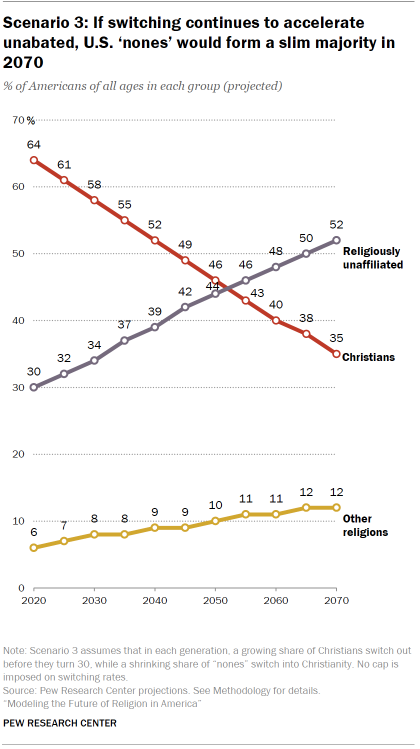

Scenario 3: Rising disaffiliation without limits

Since the 1990s, each cohort of young adults has disaffiliated from Christianity at higher rates than the one before it. At the same time, steadily fewer people have become affiliated with any religion after growing up with no religion. If this trend of change between cohorts continues, growing shares will continue to become unaffiliated during young adulthood, and declining shares will offset this attrition through conversion into a religion.

In this scenario, the share of Christians who disaffiliate by the time they reach 30 continues to rise with each successive generation and is allowed to grow without any imposed limit.

If the rate of disaffiliation among young adults continues to increase unabated, there would be a steep, rapid drop in the share of Christians who retain the identity they were raised with. The unaffiliated would surpass Christians as the largest group by 2055, when 43% of Americans would be Christian, compared with 46% who would be religiously unaffiliated. By 2070, a slim majority of Americans (52%) would be unaffiliated, while a little over a third (35%) would be Christian.

By 2070, this scenario projects that the pace of disaffiliation would have sped up so that 65% of Americans who were raised Christian would switch out before the age of 30 (up from 31% in 2020), mostly in the direction of the unaffiliated. Christian retention – the share of people raised Christian who are still Christian – would fall to 35%. Under these conditions, the share of young adults switching from an unaffiliated upbringing to a Christian adulthood would fall to 2% by 2070, compared with the recent rate of 21%.

These assumptions result in the largest shift toward disaffiliation of any projection scenario. This scenario projects an unaffiliated plurality in 30 years and is the only one to result in an unaffiliated majority in 2070.

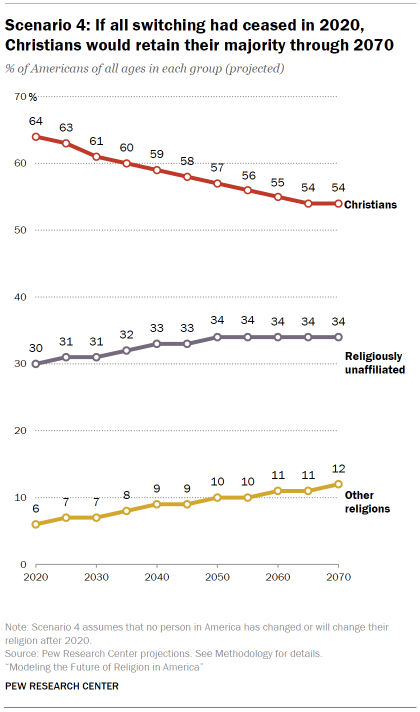

Scenario 4: No switching

For the sake of demonstrating the impact of switching on religious change, this scenario assumes that all religious switching stopped in 2020. If all other factors of change – including intergenerational transmission, migration and fertility – continued steadily but there was no further movement into and out of any religion, Christians would still make up a 54% majority of Americans in 2070. This is the only scenario modeled under which Christians maintain a majority over the next 50 years.

But the share of Christians would still decline, while the religiously unaffiliated would continue to edge up (from 30% to 34%). This is largely because Christians are older than the other groups, on average. About half of Americans in their early 20s are Christian, compared with more than three-quarters of those in their early 60s and even greater shares of older adults. As older people die, and as younger, unaffiliated people become parents to unaffiliated children, the Christian share of the population would naturally fall due to Christian deaths outnumbering Christian births.

Other religions would remain on their trajectory to reach 12% by 2070, mainly because immigration is still projected to continue in this scenario.

Why the flow of people out of Christianity may eventually lose momentum

There are many different ways of measuring the momentum of switching into and out of Christianity. This analysis focuses on switching among people under 30, because that is when most religious switching happens, and also because it helps researchers quantify the trend among young people to project forward.

Another helpful way of measuring switching momentum is by looking at all U.S. adults who have left or joined Christianity, regardless of when they did so. This wider lens amplifies an interesting fact about the way demographic change works: When a majority group starts losing members to a minority group, even small percentages of people leaving the majority group can have a large impact on the total numbers in the minority group. However, as the groups become more similar in size, the net impact of roughly equal percentages of people switching from each group to the other diminishes. Accordingly, the change in the projected sizes of these populations becomes more gradual over time in most projection scenarios, as the groups converge in size.

Let’s take switching rates for all U.S. adults as an example. In 2019, among all U.S. adults, 23% of all people who had been raised Christian had become unaffiliated, while 27% of those who had been raised without a religion had become Christian.

Though these percentages are similar (and may even seem to favor movement into Christianity) they represent vastly different numbers of people and a much larger gain for the unaffiliated. Only 12% of adults – approximately 30 million – were raised unaffiliated, and 83% – or roughly 215 million – were raised Christian. This means that by 2019, about 50 million adults (23% of 215 million) had discarded a Christian identity, and fewer than 8 million (27% of 30 million) had become Christian after an unaffiliated upbringing. Even if 100% of adults who were raised unaffiliated (all 30 million) had become Christians, the unaffiliated category still would have gained more members than it lost.

The same dynamic applies to the transmission of religion from mothers to children. In 2019, 17% of Christian mothers were raising children who – by the time they reached the teenage years – were not affiliated with any religious group. A similar share of unaffiliated mothers (11%) had teens who identified as Christians. The consequences of this 6-point gap are exaggerated because there are so many more Christian mothers than unaffiliated mothers. The difference in the number of children moving into each group would be much smaller if the two groups were of comparable size.

As the unaffiliated grow to represent a share of the population that is similar to the Christian share, relatively modest shifts in transmission and retention rates could reverse the groups’ trajectories. For example, among all U.S. adults, Christianity has attracted a greater share of people raised unaffiliated than vice versa (27% compared with 23%). The pattern is opposite among young adults, for whom being raised unaffiliated is “stickier” than being raised Christian. However, a shift back to the pattern currently observed among all adults (with higher retention rates among Christians than among the unaffiliated) could be enough – depending on other patterns – to begin growing the Christian population from a new starting point at which Christians are smaller in number than, or similar in size to, the unaffiliated. While this bottoming out and regrowth of Christianity is theoretically possible, it would require a reversal of the current trends in switching.

Projecting to 2100

If trends are projected for an even longer period, change slows under most scenarios. Even in the most extreme switching scenario, in which each cohort of young adults disaffiliates more than the one before it, with no floor imposed for Christian retention, Christians would still represent about a quarter of the population in 2100. Under other scenarios, the rate of growth of the religiously unaffiliated (and decline of Christians) is curbed by 2080. This is due to switching dynamics. If the Christian and unaffiliated populations become similar in size – an eventuality under most scenarios – and if the gap between their retention rates remains small, then the growth of the unaffiliated eventually would slow, and the religious groups could reach equilibrium rather than one group ascending completely and the other disappearing.

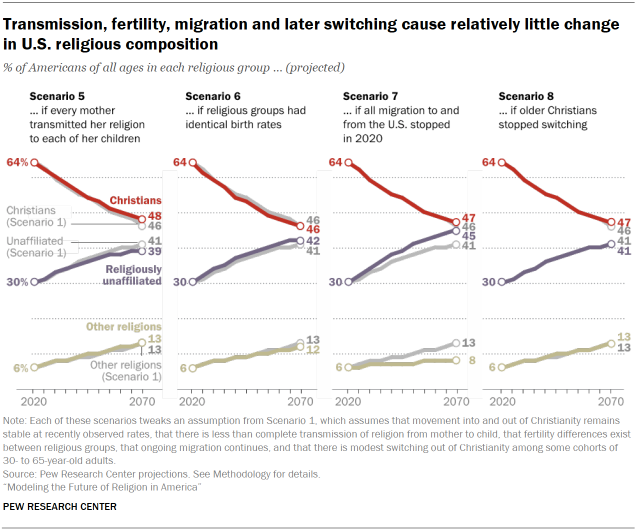

Additional scenarios: What if migration stops or people stop switching after the age of 30?

This report focuses on four main scenarios that explore how the U.S. religious landscape might change if switching out of Christianity among young adults were to speed up, keep a steady pace or stop entirely. These scenarios seek to explore the effect of religious switching in late adolescence and early adulthood, and they hold steady other demographic forces that can cause a country’s religious composition to change – namely intergenerational “transmission” (the passing of religious identity from parents to children), switching later on in adulthood, migration, fertility and mortality.

But how impactful are these other factors, and how could variations in them affect the future of religion in America? To measure the relative impact of some of the assumptions built into the model, researchers created four more scenarios that turn off one mechanism of change at a time. Otherwise, these four scenarios are identical to Scenario 1, in that they assume a steady rate of religious switching among young adults, without any acceleration. (This does not necessarily mean that Scenario 1 is the most plausible.) Turning off one mechanism of change at a time is the best way to assess whether it has any meaningful sway on the overall outcome.

The results of this statistical exercise produce small deviations from Scenario 1, on which they all are based. In other words, even if we vary our assumptions about migration – or fertility rates, or transmission rates, or the future rate of switching among older adults – the projections would be similar to those from Scenario 1.

Turning off any one of these mechanisms of demographic change results in a projected Christian share ranging from 46% to 48% in 2070. The religiously unaffiliated share would rise to between 39% and 45%, depending on which component stopped. And people of all other religious groups would be projected to make up between 8% and 13% of the U.S. population in 2070.

The scenarios in this report demonstrate that switching is the driving force behind religious change in the U.S. today. Scenario 4 illustrates that age structure is also consequential – Christians are expected to shrink and the unaffiliated to grow in part because Christians are older and the unaffiliated are younger, on average. However, Scenarios 5-8 demonstrate that other demographic factors are expected to have less impact on the overall direction and pace of change.

Scenario 5: What if every mother transmitted her religion to each of her children?

Transmission is the process of children taking on the same religious identity as their parents. Today, about 85% of teens with a religious identity classified as Christian, unaffiliated or other religion have a mother whose identity is classified in the same group, according to analysis of surveys that measure the religious identities of both teens and parents in the same household. In projections, transmission is based on the share of mothers who successfully transmit their religion. Fathers matter, too, but mothers tend to be more successful at transmission, and about a quarter of U.S. children live with single parents, who are overwhelmingly mothers.

If rates of religious transmission between mothers and children increased to 100% – in other words, if every mother transmitted her religious identity to every child she has – the unaffiliated would grow slightly less, to 39% of the U.S. population by the end of the projection period (compared with 41% under Scenario 1). This indicates that over the long term, it makes little difference whether all teens or just 85% inherit their mother’s faith (or lack thereof).

Scenario 6: What if religious groups had children at identical rates?

Over a 50-year period, the impact of fertility is also small. Scenario 6 is identical to the “steady switching” scenario except that differences in fertility rates across religious groups are turned off. If there were no differences in fertility among Christians, the religiously unaffiliated and people of other religions, Christians would be projected to shrink to 46% of the U.S. population in 2070 (the same as in Scenario 1), while the unaffiliated would grow by 1 percentage point more. The percentage estimate for people of other religions would be 1 point lower without fertility differences, as long as all other conditions mirrored Scenario 1.

Scenario 7: What if all immigration and emigration ceased?

People of non-Christian faiths make up a larger proportion of recent immigrants than they do of the overall population, and their numbers would be most affected in a “no migration” scenario. If no migrants entered or left the U.S. after 2020, people of other (i.e., non-Christian) religions would grow to represent only 8% of the population by 2070, rather than the 12% or 13% projected under scenarios accounting for steady migration. The unaffiliated would make up a slightly larger share of the population (45%) compared with Scenario 1 (41%). The 2070 Christian share of the U.S. population is similar in Scenarios 1 and 7, suggesting that continuation of the current migration patterns would have a relatively small long-term impact on the size of the Christian population, though immigrants are adding substantially to the population that identifies with other religions.

Scenario 8: What if older Christians stopped switching?

Most of the scenarios assume that about 7% of adults in some older cohorts who were raised Christian leave Christianity between the ages of 30 and 65, as they have since the 1990s. As noted above, however, there are reasons to believe that this pattern of religious switching in older adulthood is the result of a period effect and may not continue forever.17 Under a “no switching after 30” scenario, future religious identity change occurs only in young adulthood, steadily at recently observed rates. The end result of Scenario 8 is similar to Scenario 1: 47% of the U.S. population would be Christian in 2070 (versus 46% in Scenario 1), while the share of nones (41%) and people with other religions (13%) is the same in both scenarios. Without ongoing defection from Christianity among adults over 30, the Christian population would only be slightly larger.