If recent trends in religious switching continue, Christians could make up less than half of the U.S. population within a few decades

This report seeks to answer the question: What might the religious makeup of the United States look like roughly 50 years from now, in 2070, if recent trends continue? We try to address this not with sweeping predictions or grand theories, but with mathematical projections that combine techniques standardly used in demography (the study of human populations) with data we have collected in surveys on religion.

Demographers project the growth or shrinkage of populations based on factors such as age, sex, fertility, mortality and migration. For religious populations, projections also need to include data on “switching” – voluntary movement into and out of religious groups. Finally, the shifting sizes of U.S. religious groups depend partly on rates of religious transmission – whether parents pass their religious identity on to their children. In this report, Pew Research Center has incorporated estimates of “intergenerational transmission of religion” into our projections for the first time.

Switching rates are estimated based on responses from more than 15,000 adults to two questions posed in a 2019 Pew Research Center survey: “In what religion, if any, were you raised?” and “What is your present religion, if any?” Results were weighted to the Center’s National Public Opinion Reference Survey, conducted by mail and online in 2020. Long-term cohort trends in switching (going back to the 1970s) come from two similar questions in the long-running General Social Survey: “In what religion were you raised?” and “What is your religious preference?”

Shifts in religious identity, or switching, are concentrated among young adults. During earlier childhood years, a parent’s religion (or lack thereof) is often, but not always, transmitted to a child. Rates of transmission for three identity categories (Christian, other religion, and religiously unaffiliated) are estimated based on the percentages of teens (ages 13 to 17) who shared their mother’s religious affiliation in a 2019 survey of 1,811 pairs of U.S. parents and teens. These observed patterns are used to model whether future generations of newborn children inherit their mother’s religion.

Group differences in fertility (the number of children women tend to have), migration and age structures also drive change. Fertility differences by religion are based on the National Survey of Family Growth, while the average U.S. fertility rate used in each period is based on the 2019 revision of United Nations World Populations Prospect data. Migration data comes from the UN. Religious composition by age and sex groups is based on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. We estimate the religious composition of children based on the religious composition of young adults, and fertility patterns.

The various input data is used in projection models to illustrate what the future religious composition of the U.S. might look like under a range of hypothetical scenarios. See Methodology for more information on inputs and modeling.

Since the 1990s, large numbers of Americans have left Christianity to join the growing ranks of U.S. adults who describe their religious identity as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” This accelerating trend is reshaping the U.S. religious landscape, leading many people to wonder what the future of religion in America might look like.

What if Christians keep leaving religion at the same rate observed in recent years? What if the pace of religious switching continues to accelerate? What if switching were to stop, but other demographic trends – such as migration, births and deaths – were to continue at current rates? To help answer such questions, Pew Research Center has modeled several hypothetical scenarios describing how the U.S. religious landscape might change over the next half century.

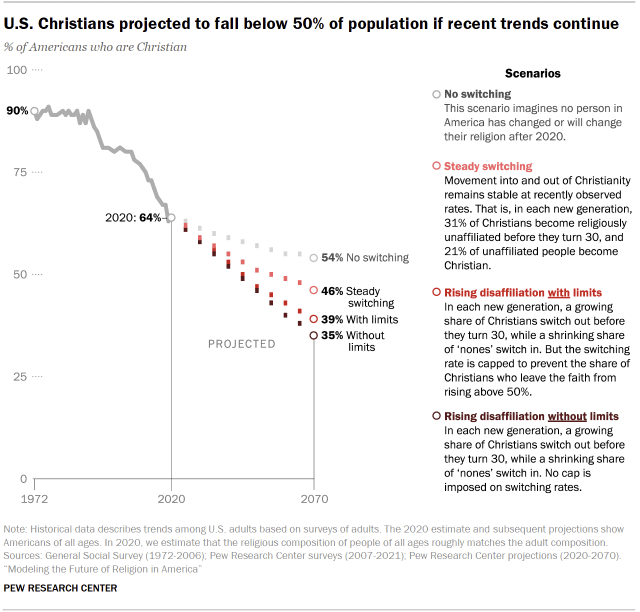

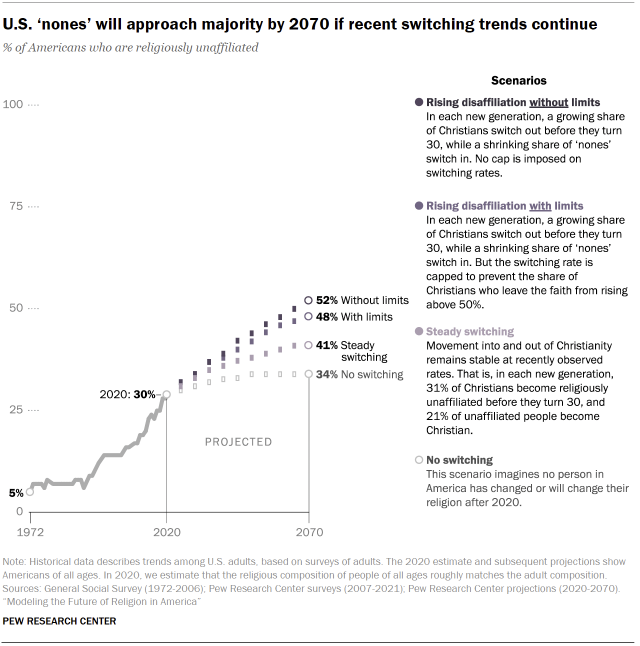

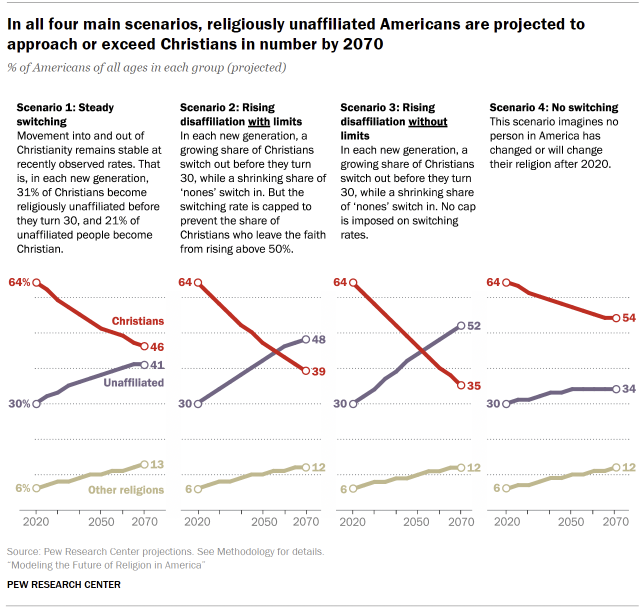

The Center estimates that in 2020, about 64% of Americans, including children, were Christian. People who are religiously unaffiliated, sometimes called religious “nones,” accounted for 30% of the U.S. population. Adherents of all other religions – including Jews, Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists – totaled about 6%.1

Depending on whether religious switching continues at recent rates, speeds up or stops entirely, the projections show Christians of all ages shrinking from 64% to between a little more than half (54%) and just above one-third (35%) of all Americans by 2070. Over that same period, “nones” would rise from the current 30% to somewhere between 34% and 52% of the U.S. population.

Switching, which in some cases could be described as religious conversion, is defined in this report as a change between the religion in which a person was raised (in childhood) and their present religious identity (in adulthood).

Current rates of switching are based on responses from more than 15,000 adults to two questions posed in a 2019 Pew Research Center survey: “In what religion, if any, were you raised?” and “What is your present religion, if any?”

In many cases, switching does not happen in a single moment. Religious “nones” often describe their disaffiliation as a gradual process, and some may never have felt a strong connection to a religious identity, even though they describe themselves as having been raised in a faith tradition.

However, these are not the only possibilities, and they are not meant as predictions of what will happen. Rather, this study presents formal demographic projections of what could happen under a few illustrative scenarios based on trends revealed by decades of survey data from Pew Research Center and the long-running General Social Survey.

All the projections start from the current religious composition of the U.S. population, taking account of religious differences by age and sex. Then, they factor in birth rates and migration patterns. Most importantly, they incorporate varying rates of religious switching – movement into and out of broad categories of religious identity – to model what the U.S. religious landscape would look like if switching stayed at its recent pace, continued to speed up (as it has been doing since the 1990s), or suddenly halted.

Switching rates are based on patterns observed in recent decades, through 2019. For example, we estimate that 31% of people raised Christian become unaffiliated between ages 15 to 29, the tumultuous period in which religious switching is concentrated.2 An additional 7% of people raised Christian become unaffiliated later in life, after the age of 30.

While the scenarios in this report vary in the extent of religious disaffiliation they project, they all show Christians continuing to shrink as a share of the U.S. population, even under the counterfactual assumption that all switching came to a complete stop in 2020. At the same time, the unaffiliated are projected to grow under all four scenarios.

Under each of the four scenarios, people of non-Christian religions would grow to represent 12%-13% of the population – double their present share. This consistency does not imply more certainty or precision compared with projections for Christians and “nones.” Rather, the growth of other religions is likely to hinge on the future of migration (rather than religious switching), and migration patterns are held constant across all four scenarios. (See Chapter 2 for an alternative scenario involving migration.)

Of course, it is possible that events outside the study’s model – such as war, economic depression, climate crisis, changing immigration patterns or religious innovations – could reverse current religious switching trends, leading to a revival of Christianity in the United States. But there are no current switching patterns in the U.S. that can be factored into the mathematical models to project such a result.

None of these hypothetical scenarios is certain to unfold exactly as modeled, but collectively they demonstrate how much impact switching could have on the overall population’s religious composition within a few decades. The four main scenarios, combined with four alternatives outlined in Chapter 2, show that rates of religious switching in adulthood appear to have a far greater impact on the overall religious composition of the United States than other factors that can drive changes in affiliation over time, such as fertility rates and intergenerational transmission (i.e., how many parents pass their religion to their children).

The decline of Christianity and the rise of the “nones” may have complex causes and far-reaching consequences for politics, family life and civil society. However, theories about the root causes of religious change and speculation about its societal impact are not the focus of this report. The main contribution of this study is to analyze recent trends and show how the U.S. religious landscape would shift if they continued.

This report focuses on Christians and the religiously unaffiliated, the two most common, very broad religious identities in the United States today. People with all other religious affiliations are combined into an umbrella category that includes Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists and a diverse array of smaller groups that together make up about 6% of the U.S. population. In 2015, Pew Research Center projected the growth of several of these groups separately, both in the U.S. and around the world, and the Center may do so again in the future. But, because data on religious switching and intergenerational transmission is less reliable for groups with small sample sizes in surveys, non-Christian groups are not shown separately in this report.

The report also does not project change for subgroups of Christians, such as Protestants and Catholics, or for subgroups of “nones,” such as atheists, agnostics and people who describe their religion as “nothing in particular.” For the latest figures on the religious composition of the U.S., including some subgroups, see our 2021 report, “About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated.”

Scenario assumptions and projection results

The four main scenarios presented here vary primarily in their assumptions about the future of religious switching among Americans between the ages of 15 and 29 – which are the years when most religious change happens. Only a modest amount of switching is modeled among older adults.

Fertility and mortality rates are held steady, as are rates of intergenerational transmission. In each scenario, the groups begin with their current profiles in terms of age and gender. Christians, for example, are older than the religiously unaffiliated, on average, and include a higher share of women.

Finally, the models assume that migration remains constant, which helps explain why non-Christian groups follow the same trajectory in each of the four scenarios. Immigration has an outsized effect on the composition of non-Christian groups in the U.S. because adherents of religions like Islam and Hinduism make up a larger share of new arrivals than they do of the existing U.S. population.

Chapter 2 presents four additional scenarios that explore the impact of the factors held constant here. These additional projections show how the U.S. religious landscape might change if current switching patterns held steady, but intergenerational religious transmission occurred in 100% of cases; there were no fertility differences by religion; there was no switching after age 30; or there was no migration after 2020.

The alternative scenarios are intended to help isolate – and thereby illuminate – the impact of various factors. One might think of the projections as an experiment in which some key drivers of religious composition change are turned on or off, sped up or slowed down, to see how much difference they make. For more information about modeling assumptions and results, see Chapter 2 and the Methodology.

Scenario 1: Steady switching – Christians would lose their majority but would still be the largest U.S. religious group in 2070

Switching assumption: Switching into and out of Christianity, other religions and the religiously unaffiliated category (“nones”) continues among young Americans (ages 15 to 29) at the same rates as in recent years. Most significantly, each new generation sees 31% of people who were raised Christian become religiously unaffiliated by the time they reach 30, while 21% of those who grew up with no religion become Christian.

Outcome: If switching among young Americans continued at recent rates, Christians would decline as a share of the population by a few percentage points per decade, dipping below 50% by 2060. In 2070, 46% of Americans would identify as Christian, making Christianity a plurality – the most common religious identity – but no longer a majority. In this scenario, the share of “nones” would not climb above 41% by 2070.

Scenario 2: Rising disaffiliation with limits – ‘nones’ would be the largest group in 2070 but not a majority

Switching assumption: Continuing a recent pattern, switching out of Christianity becomes more common among young Americans as each generation sees a progressively larger share of Christians leave religion by the age of 30. However, brakes are applied to keep Christian retention (the share of people raised as Christians who remain Christian) from falling below about 50%.3 At the same time, switching into Christianity becomes less and less common, also continuing recent trends.

Outcome: If the pace of switching before the age of 30 were to speed up initially but then hold steady, Christians would lose their majority status by 2050, when they would be 47% of the U.S. population (versus 42% for the unaffiliated). In 2070, “nones” would constitute a plurality of 48%, and Christians would account for 39% of Americans.

Scenario 3: Rising disaffiliation without limits – ‘nones’ would form a slim majority in 2070

Switching assumption: The share of Christians who disaffiliate by the time they reach 30 continues to rise with each successive generation, and rates of disaffiliation are allowed to continue rising even after Christian retention drops below 50% (i.e., no limit is imposed). As in Scenario 2, switching into Christianity among young Americans becomes less and less common.

Outcome: If the pace of switching before the age of 30 were to speed up throughout the projection period without any brakes, Christians would no longer be a majority by 2045. By 2055, the unaffiliated would make up the largest group (46%), ahead of Christians (43%). In 2070, 52% of Americans would be unaffiliated, while a little more than a third (35%) would be Christian.

Scenario 4: No switching – Christians would retain their majority through 2070

Switching assumption: This scenario imagines no person in America has changed or will change their religion after 2020. But even in that hypothetical situation, the religious makeup of the U.S. population would continue to shift gradually, primarily as a result of Christians being older than other groups, on average, and the unaffiliated being younger, with a larger share of their population of childbearing age.

Outcome: If switching had stopped altogether in 2020, the share of Christians would still decline by 10 percentage points over 50 years, reaching 54% in 2070. The unaffiliated would remain a substantial minority, at 34%.

Which scenario is most plausible?

The scenarios in this report present a wide range of assumptions and outcomes. Readers may wonder which scenario is most plausible. While there are endless possibilities that would lead to religious composition change that is different from the plotted trajectories, it may be helpful to consider how closely the hypothetical switching scenarios adhere to real, observed trends.

The “no switching” scenario (No. 4) is not realistic – switching has not ended and there is no reason to think it will come to an abrupt stop. The purpose of this scenario is to show the influence of demographic factors (such as age and fertility) on religious affiliation rates. Still, if fewer future young adults switch from Christianity to no affiliation, or if movement in the opposite direction increases, the future religious landscape might resemble the results of this projection.

The “steady switching” scenario (No. 1) is conservative. It depicts moderate, steady “net” switching (taking into consideration some partially offsetting movement in both directions) away from Christianity among young adults for the foreseeable future, rather than the extension of a decades-long trend of increasing disaffiliation across younger cohorts. Even long-standing trends can be unsustainable or otherwise temporary, and this scenario best represents what would happen if the recent period of rising attrition from Christianity is winding down or already has ended.

By contrast, the scenario of rising disaffiliation without limits (No. 3) assumes there is a kind of ever-increasing momentum behind religious switching. The visible rise of the unaffiliated might induce more and more young people to leave Christianity and further increase the “stickiness” of an unaffiliated upbringing, so that fewer and fewer people raised without a religion would take on a religious identity at a later point in their lives.

Intergenerational transmission is the passing of religious identity from parents to children. It occurs (or fails to occur) in childhood. In this study, transmission rates are calculated based on the share of children who inherit their mother’s religion (or their mother’s unaffiliated identity) because mothers tend to successfully transmit their religious identities more often than fathers do. Also, roughly a quarter of children under 18 live in single-parent households, which are overwhelmingly headed by mothers.

The Center’s data shows the vast majority of teens (about 85%) have the same religious identity as their mother, while 16% report a different identity. Religious transmission, as measured in this study, can fail to occur for many reasons and in either direction. For example, if a mother doesn’t identify with any religion but her 14-year-old child identifies as Christian, it’s counted as a non-transmission of religious identity – just as it would for a Christian mother with a religiously unaffiliated teen.

Intergenerational transmission differs from switching because it describes what happens before the age of 15 and is measured by comparing the religious affiliation of mothers with the affiliations reported by their teenage children. Switching, by contrast, describes a change that happens after the age of 15; it is measured by comparing the religions in which respondents say they were raised with the affiliations they report today.

On the other hand, highly religious parents tend to raise highly religious children who are less likely than children of less religious parents to disaffiliate in young adulthood. As a result, there may continue to be a self-perpetuating core of committed Christians who retain their religion and raise new generations of Christians. It may be useful to consider the experience of other countries in which data on religious switching is available. In 79 other countries analyzed (with a variety of religious compositions), most of the 30- to 49-year-olds who report that they were raised as Christians still identify as Christian today; in other words, the Christian retention rate in those countries has not been known to fall below about 50%.4 The “rising disaffiliation with limits” scenario (No. 2) best illustrates what would happen if recent generational trends in the U.S. continue, but only until they reach the boundary of what has been observed around the world, including in Western Europe. Overall, this scenario seems to most closely fit the patterns observed in recent years.

None of the scenarios in this report demonstrate what would happen if switching into Christianity increased. This is not because a religious revival in the U.S. is impossible. New patterns of religious change could emerge at any time. Armed conflicts, social movements, rising authoritarianism, natural disasters or worsening economic conditions are just a few of the circumstances that sometimes trigger sudden social – and religious – upheavals. However, our projections are not designed to model the consequences of dramatic events, which might affect various facets of life as we know it, including religious identity and practice. Instead, these projections describe the potential consequences of dynamics currently shaping the religious landscape.

Is switching only for the young?

Most people don’t change their religious identity. But among those who do, the switch typically happens between the ages of 15 and 29. That is why this report focuses on switching among young Americans.

However, since the rise of the “nones” began in the 1990s, a pattern has emerged in which a measurable share of adults ages 30 to 65 also disaffiliate from Christianity. The Center’s analysis of U.S. and international data indicates that modest levels of disaffiliation among older adults could be a stage that Christian-majority countries go through when Christian identity stops being widely taken for granted – until about 30% of those raised Christian already have shed Christian identity by the time they reach 30.

Today, among Americans who recently turned 30 and grew up Christian, disaffiliation rates are already above 30%, so the projection models assume that, on average, they will not switch religions again. However, among groups of older adults born after World War II, we model ongoing switching in which 7% of Americans who were raised Christian will switch out between the ages of 30 and 65. This rate of switching among older adults is held constant in each projection model except the no-switching scenario, which does not include any switching among older or younger adults. Switching by religiously unaffiliated, older Americans into Christianity is not modeled in the projections because there is no clear trend in this direction.

For more details on later adult switching, see the Methodology and Appendix B.

Religious change in context

These projections indicate the U.S. might be following the path taken over the last 50 years by many countries in Western Europe that had overwhelming Christian majorities in the middle of the 20th century and no longer do. In Great Britain, for example, “nones” surpassed Christians to become the largest group in 2009, according to the British Social Attitudes Survey.5 In the Netherlands, disaffiliation accelerated in the 1970s, and 47% of adults now say they are Christian.

While the change in affiliation rates in the United States is largely due to people voluntarily leaving religion behind, switching is not the only driver of religious composition change worldwide. For example, differences in fertility rates explain most of the recent religious change in India, while migration has altered the religious composition of many European countries in the last century. Forced conversions, mass expulsions, wars and genocides also have caused changes in religious composition throughout history.

Moreover, the scenarios in this report are limited to religious identity and do not project how religious beliefs and practices might change in the coming decades.

Along with the decline in the percentage of U.S. adults who identify as Christian in recent years, Pew Research Center surveys have found declining shares of the population who say they pray daily or consider religion very important in their lives. Still, it is an open question whether the Christian population in the future will be more or less highly committed than U.S. Christians are today.

On the one hand, within each generation, Christians with lower levels of religious commitment may be most likely to shed their identity and become religiously unaffiliated, while new converts may bring greater zeal. These dynamics could lead to rising levels of commitment in the remaining Christian population. On the other hand, religious commitment could steadily weaken from generation to generation if people continue to identify as Christian but are less devout than their parents and grandparents. This dynamic could lead to steady or declining levels of belief and practice.

Meanwhile, religiously unaffiliated Americans today are not uniformly nonbelieving or nonpracticing. Many religious “nones” partake in traditional religious practices despite their lack of religious identity, including a solid majority who believe in some kind of higher power or spiritual force. It is also unclear how this may change in the future, and whether connections to these beliefs will weaken if disaffiliation becomes even more common in the broader society. At the same time, many observers have wondered what kinds of spiritual practices, if any, may fill the void left by institutional religion. We plan to continue exploring this question in future research.

This report marks the first time Pew Research Center has projected religious composition in the United States under multiple switching scenarios, and the first time that differing rates of religious transmission from parents to children have been taken into account.

These population projections were produced as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.