How often do Americans ponder why bad things happen to people?

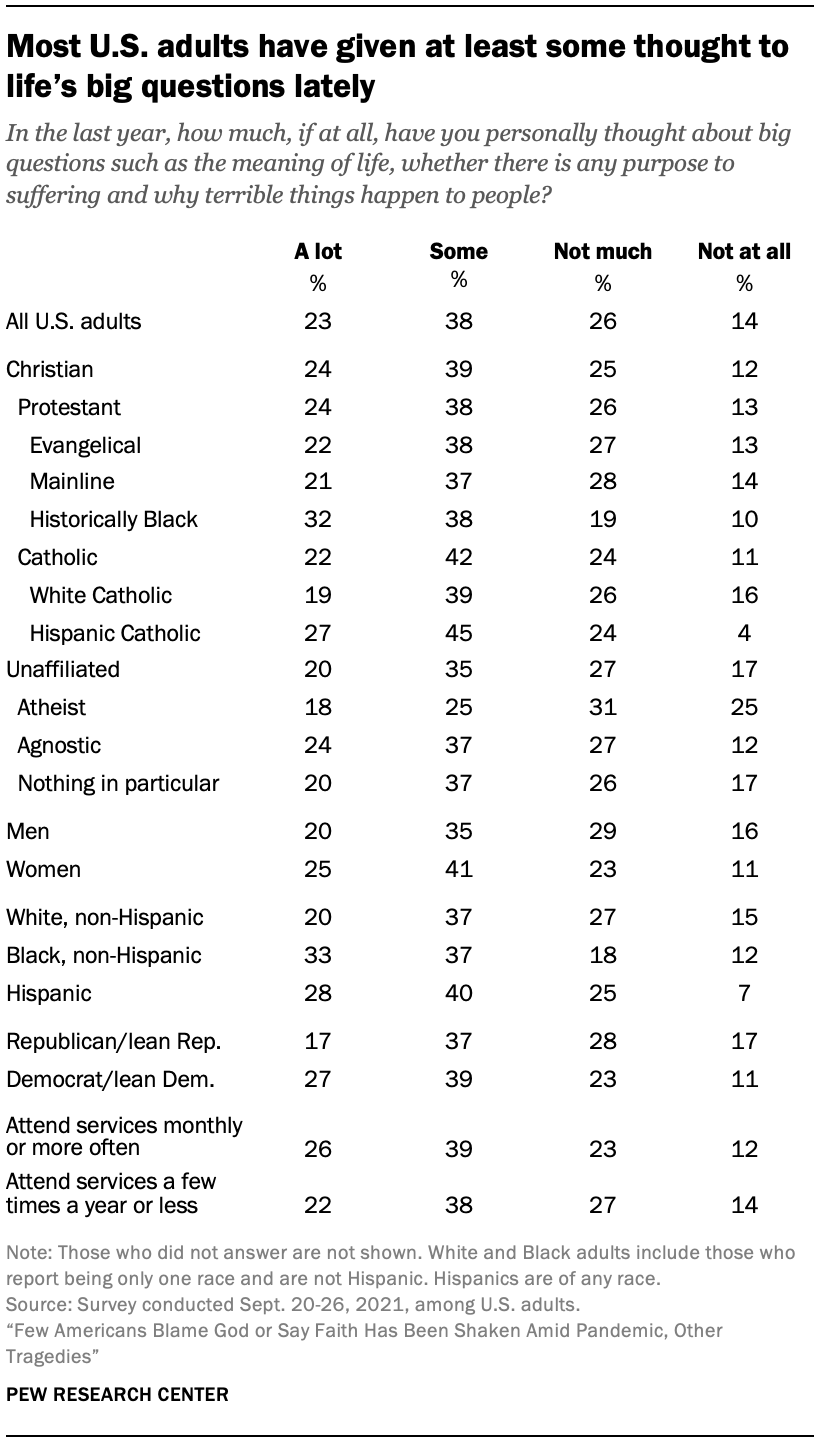

The survey asked Americans, in light of the coronavirus outbreak and other recent tragedies, how often in the past year they have thought about big questions such as the meaning of life, whether there is any purpose to suffering and why terrible things happen to people.

The survey asked Americans, in light of the coronavirus outbreak and other recent tragedies, how often in the past year they have thought about big questions such as the meaning of life, whether there is any purpose to suffering and why terrible things happen to people.

About six-in-ten U.S. adults (61%) say they have thought about these things at least “some,” including 23% who say they have pondered such weighty questions “a lot.”

Christians are somewhat more likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans (also known as religious “nones”) to say they have thought about these things. Also, Black (33%) and Hispanic (28%) Americans are more likely than White adults (20%) to say they have thought about big questions a lot in the past year.

There is little to no variation on this question based on people’s age, level of education or region of residence.

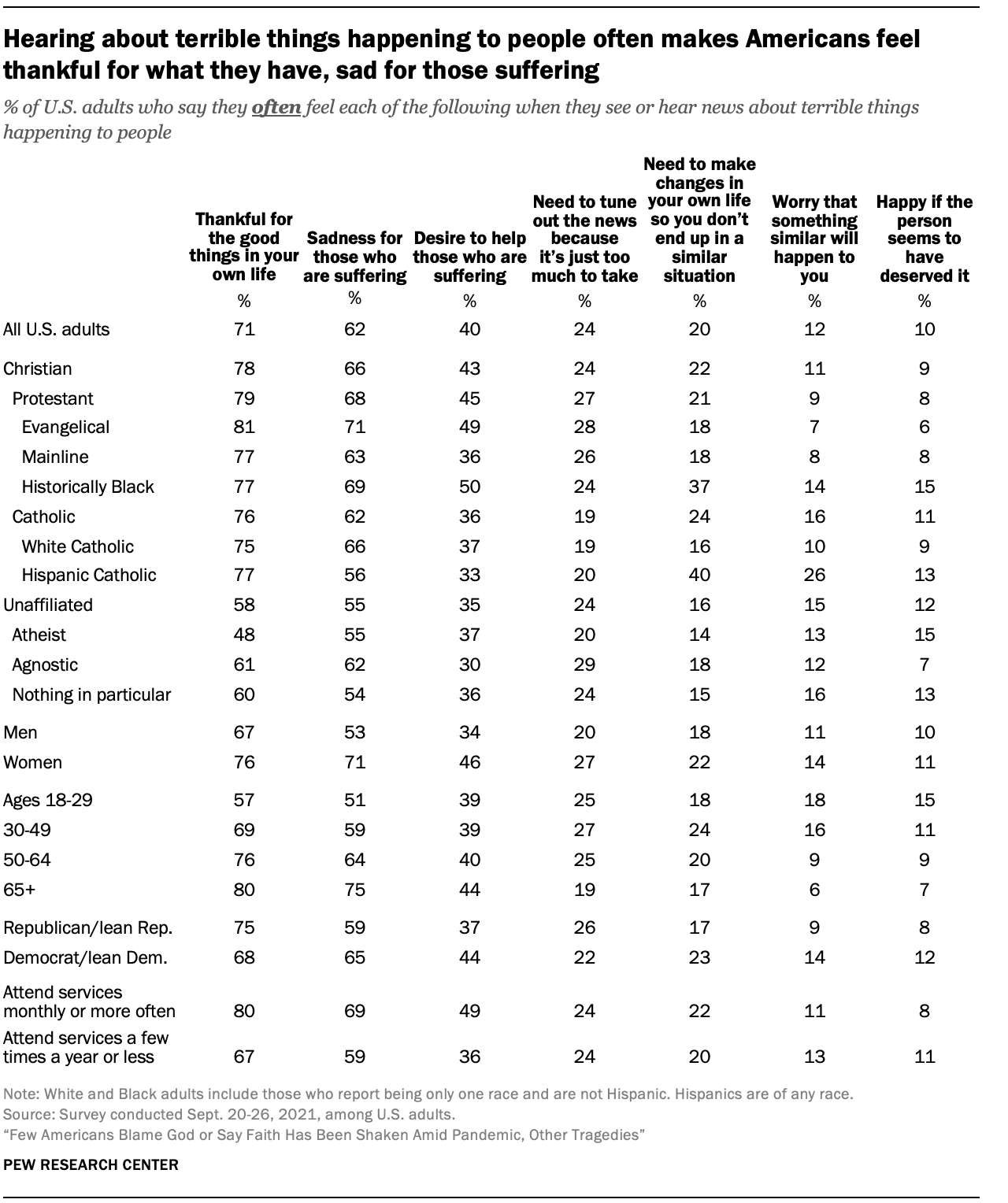

When they hear about terrible things happening to people, most Americans say they often feel thankful for the good things in their own lives (71%) and sadness for those who are suffering (62%). Christians are considerably more inclined than those without a religious affiliation to report experiencing such reactions regularly; the same is true of U.S. adults who typically attend religious services at least monthly compared with those who attend less often. Additionally, women are more likely than men, and older Americans are more likely than those who are younger, to say they feel both gratitude and sadness when they see news about terrible things happening to people.

Four-in-ten U.S. adults say they frequently feel a desire to help those who are suffering when they hear such news. Again, Christians – and especially Protestants – are more likely than religious “nones” to feel this way, as are women in comparison with men.

About a quarter of Americans (24%) say that when they hear about bad things happening to people, they often feel the need to tune out the news because it’s “just too much to take.” And one-in-five Americans say they often feel the need to make changes in their own lives so they don’t end up in a similar situation, with Black (33%) and Hispanic (32%) Americans about twice as likely as White Americans (15%) to feel this way.

When encountering bad news, roughly one-in-eight U.S. adults (12%) say they often worry that something similar will happen to them; this feeling is about twice as common among young adults (under age 30) than among those ages 50 and older. And one-in-ten say they often feel happy if a person seems to have deserved a bad outcome because of something they did or did not do (a feeling that might be described by the German word schadenfreude, which means taking pleasure in someone else’s pain or misfortune).

Although the shares who “often” have these experiences vary widely, clear majorities of Americans say they at least “sometimes” have these feelings when they hear about terrible things happening to people on six of the seven questions. The only exception is schadenfreude: About two-thirds say they rarely (34%) or never (31%) feel happiness at someone else’s suffering, even if the person seems to deserve it.

Explanations for why suffering exists in the world

The question of why suffering exists (as well as what suffering is, at its core) has been pondered by countless religious and secular thinkers. The survey offered several possible reasons for suffering, giving respondents the opportunity to say that each statement describes their own views “very well,” “somewhat well,” “not too well” or “not at all well.”

The question of why suffering exists (as well as what suffering is, at its core) has been pondered by countless religious and secular thinkers. The survey offered several possible reasons for suffering, giving respondents the opportunity to say that each statement describes their own views “very well,” “somewhat well,” “not too well” or “not at all well.”

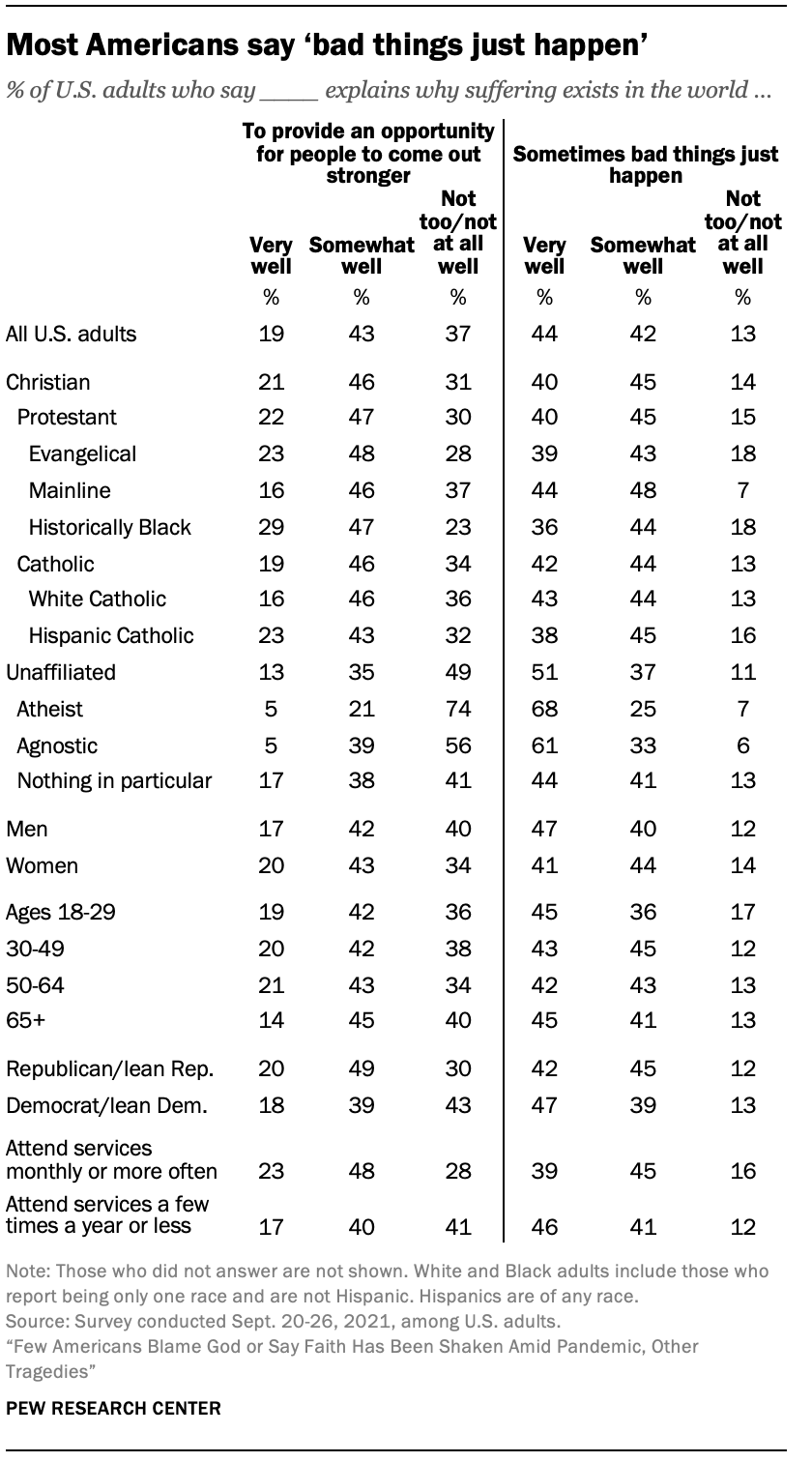

More than eight-in-ten Americans say that “sometimes bad things just happen” reflects their thinking either very well (44%) or somewhat well (42%). This perspective is especially common among atheists and agnostics, majorities of whom say the statement captures their views “very well” (68% and 61%, respectively).

Fewer U.S. adults (19%) – including just 5% of both atheists and agnostics – strongly identify with the idea that suffering exists “to provide an opportunity for people to come out stronger.” Still, 43% of Americans say this reflects their viewpoint “somewhat well.” Christians (relative to religious “nones”) and people who say they frequently attend religious services (compared with those who attend less often) are especially likely to feel this way.

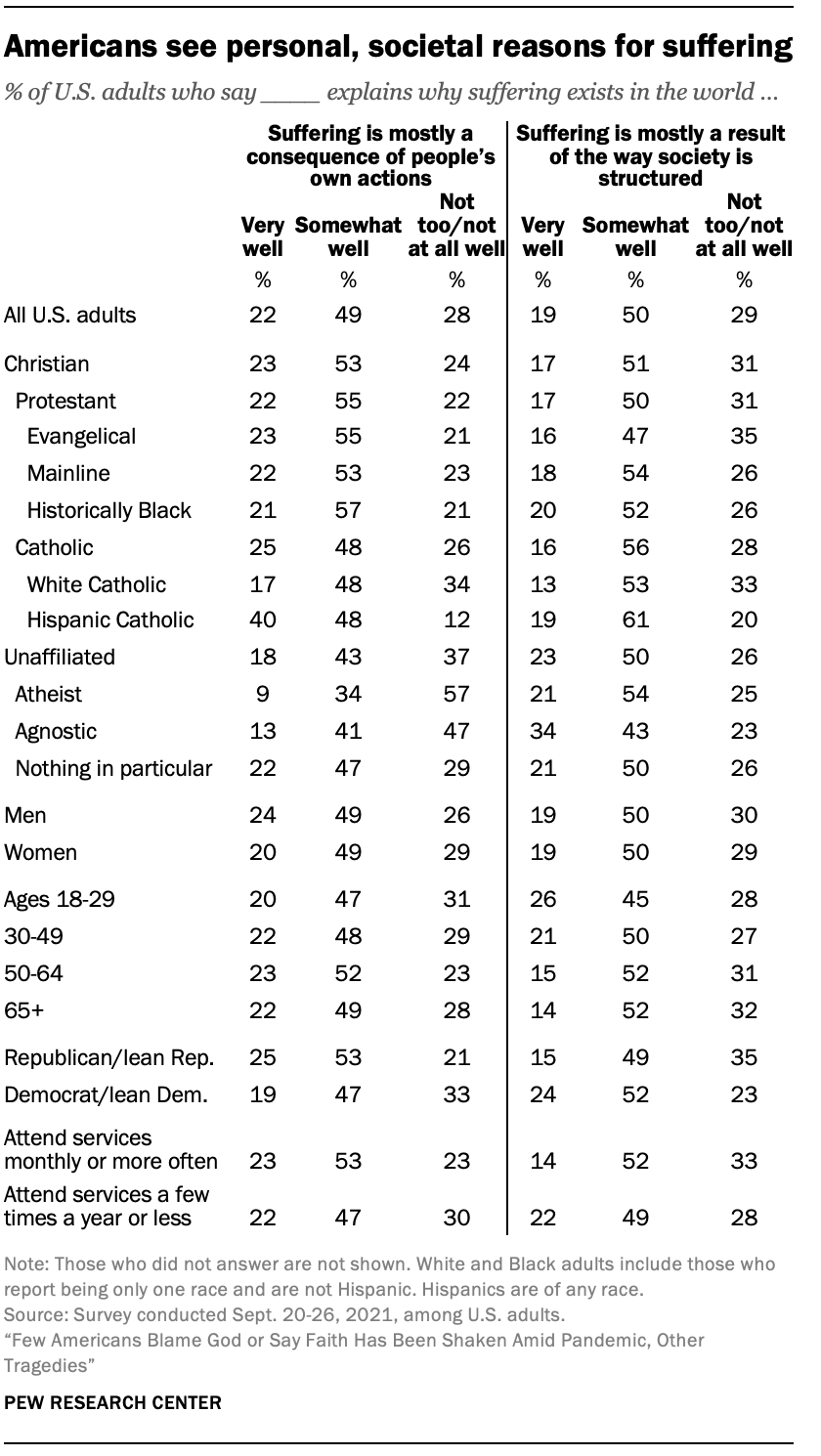

Similar shares of Americans express agreement with the following two statements: “Suffering is mostly a consequence of people’s own actions” and “Suffering is mostly a result of the way society is structured.” About seven-in-ten people surveyed say each statement explains their views at least somewhat well, although in both cases, only about one-in-five say it captures their perspective “very well.”

Similar shares of Americans express agreement with the following two statements: “Suffering is mostly a consequence of people’s own actions” and “Suffering is mostly a result of the way society is structured.” About seven-in-ten people surveyed say each statement explains their views at least somewhat well, although in both cases, only about one-in-five say it captures their perspective “very well.”

More than half of respondents (53%) say that both of these statements describe their views at least somewhat well, although just 8% say both reflect their perspective very well. More often, people say that one of these statements captures their views very well and the other somewhat well (15%), or that both reflect their views somewhat well (30%) – suggesting that many people do see both individual and societal reasons behind personal suffering, regardless of which is the primary cause.

Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party are somewhat more inclined than Republicans and GOP leaners to see suffering as more of a societal problem, while Republicans are modestly more likely to see suffering as a result of people’s own actions. Looked at another way, among all those who see suffering as a consequence of how society is structured but not of people’s own actions, three times as many are Democrats (72%) as Republicans (24%).

Views on God’s role in human suffering

To help see how Americans’ views about God intersect with their perspectives on human suffering, the survey asked Americans whether they believe in God or not. More than half of U.S. adults (58%), including eight-in-ten Christians, say they believe in God as described in the Bible. An additional 32% of Americans believe in some other kind of higher power or spiritual force, while roughly one-in-ten (9%) do not believe in God or any higher power in the universe. (For full question wording, see the topline.)

To help see how Americans’ views about God intersect with their perspectives on human suffering, the survey asked Americans whether they believe in God or not. More than half of U.S. adults (58%), including eight-in-ten Christians, say they believe in God as described in the Bible. An additional 32% of Americans believe in some other kind of higher power or spiritual force, while roughly one-in-ten (9%) do not believe in God or any higher power in the universe. (For full question wording, see the topline.)

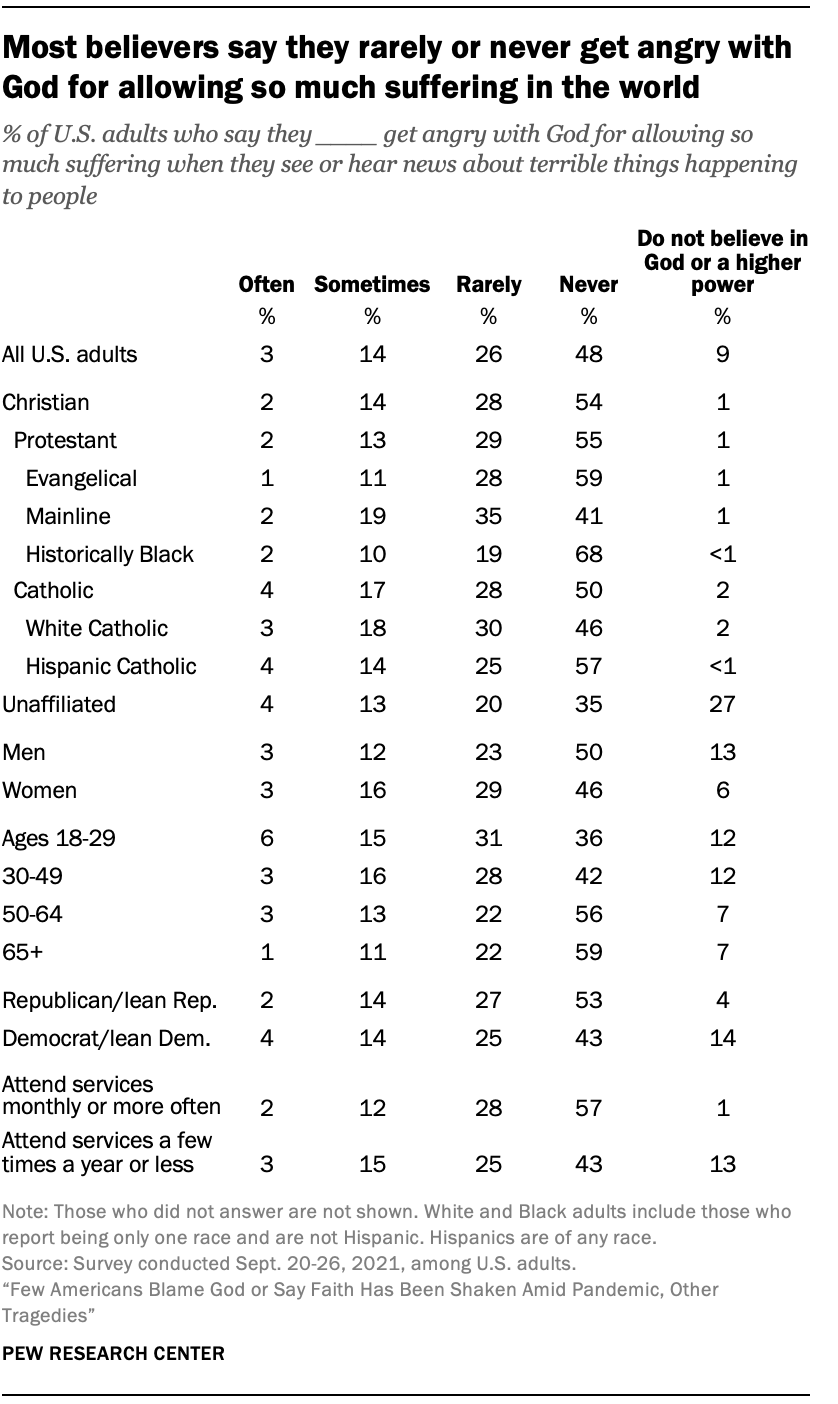

All respondents who expressed a belief in God or any kind of higher power were then asked whether, when they hear about terrible things happening to people, they get angry with God for allowing so much suffering in the world.

Relatively few U.S. adults (3%) say they feel this way “often,” while 14% say they “sometimes” experience such anger toward God. A majority of Americans say they “rarely” (26%) or “never” (48%) feel angry with God for allowing terrible things to happen to people.

Protestants in the historically Black tradition and Americans in older age cohorts are especially likely to say they never feel such anger toward God.

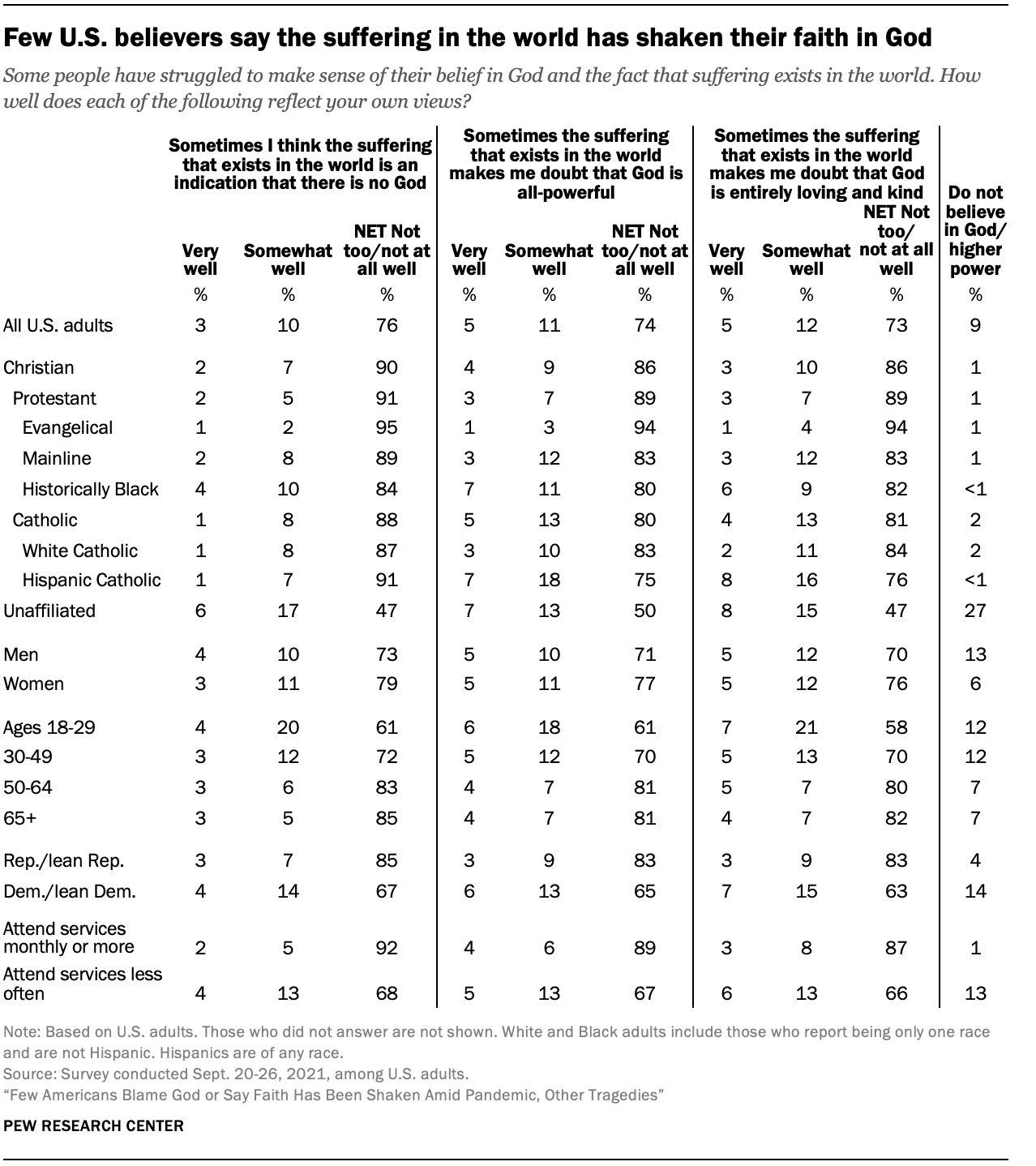

Respondents who believe in God or a higher power also were asked whether they experience doubts about those beliefs – or about certain attributes of God, such as kindness – because of the suffering they see in the world. Relatively few Americans echo such sentiments in a resounding way. For example, just 3% of U.S. adults say the following statement describes their own views very well: “Sometimes I think the suffering that exists in the world is an indication that there is no God.” Similarly, only 5% say that the statements “sometimes the suffering in the world makes me doubt that God is all-powerful” and “sometimes the suffering in the world makes me doubt that God is entirely loving and kind” describe their views very well.

Even a weaker resonance with these doubts is relatively rare. Fewer than one-in-five Americans say each of the three statements describes their views at least “somewhat well.” In each case, about three-quarters say it describes their feelings “not too well” or “not at all well.” (An additional 9% of Americans do not believe in God or any other higher power or spiritual force in the universe, and therefore were not asked these questions.)

Doubts about the existence of God or about God’s attributes based on the amount of human suffering in the world are somewhat more common among young adults, Democrats and religiously unaffiliated Americans who express a belief in God or a higher power. But even among these groups, believers are much more likely to say they do not have such doubts than to say they do.

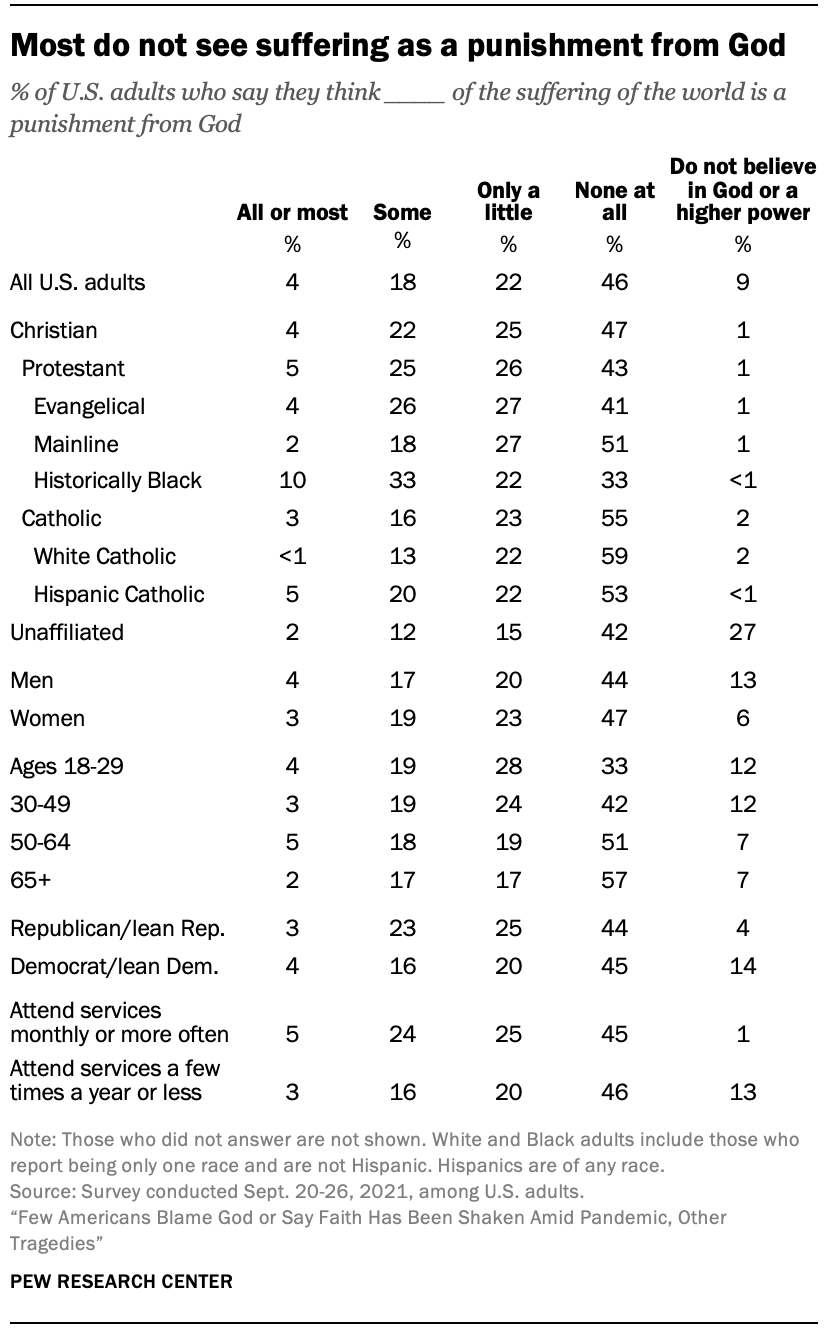

Similarly, relatively few Americans see much of the suffering in the world as a punishment from God. Just 4% say that “all” or “most” of the suffering in the world is a punishment from God, while an additional 18% say that “some” is, and 22% say that “only a little” of the world’s suffering results from God’s wrath. Nearly half of U.S. adults (46%) say “none at all” of the suffering in the world is a punishment from God (in addition to the 9% who do not believe in God).

Similarly, relatively few Americans see much of the suffering in the world as a punishment from God. Just 4% say that “all” or “most” of the suffering in the world is a punishment from God, while an additional 18% say that “some” is, and 22% say that “only a little” of the world’s suffering results from God’s wrath. Nearly half of U.S. adults (46%) say “none at all” of the suffering in the world is a punishment from God (in addition to the 9% who do not believe in God).

A 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that 40% of U.S. adults said God had ever punished them. That is similar to the share, in the new survey, who say at least “a little” of the suffering in the world is a punishment from God (44%).

Protestants in the historically Black tradition are somewhat more likely than other Christians to say at least “some” of the suffering in the world results from God’s punishment. Still, fewer than half (43%) believe this, and just one-in-ten say that all or most suffering comes from the wrath of God.

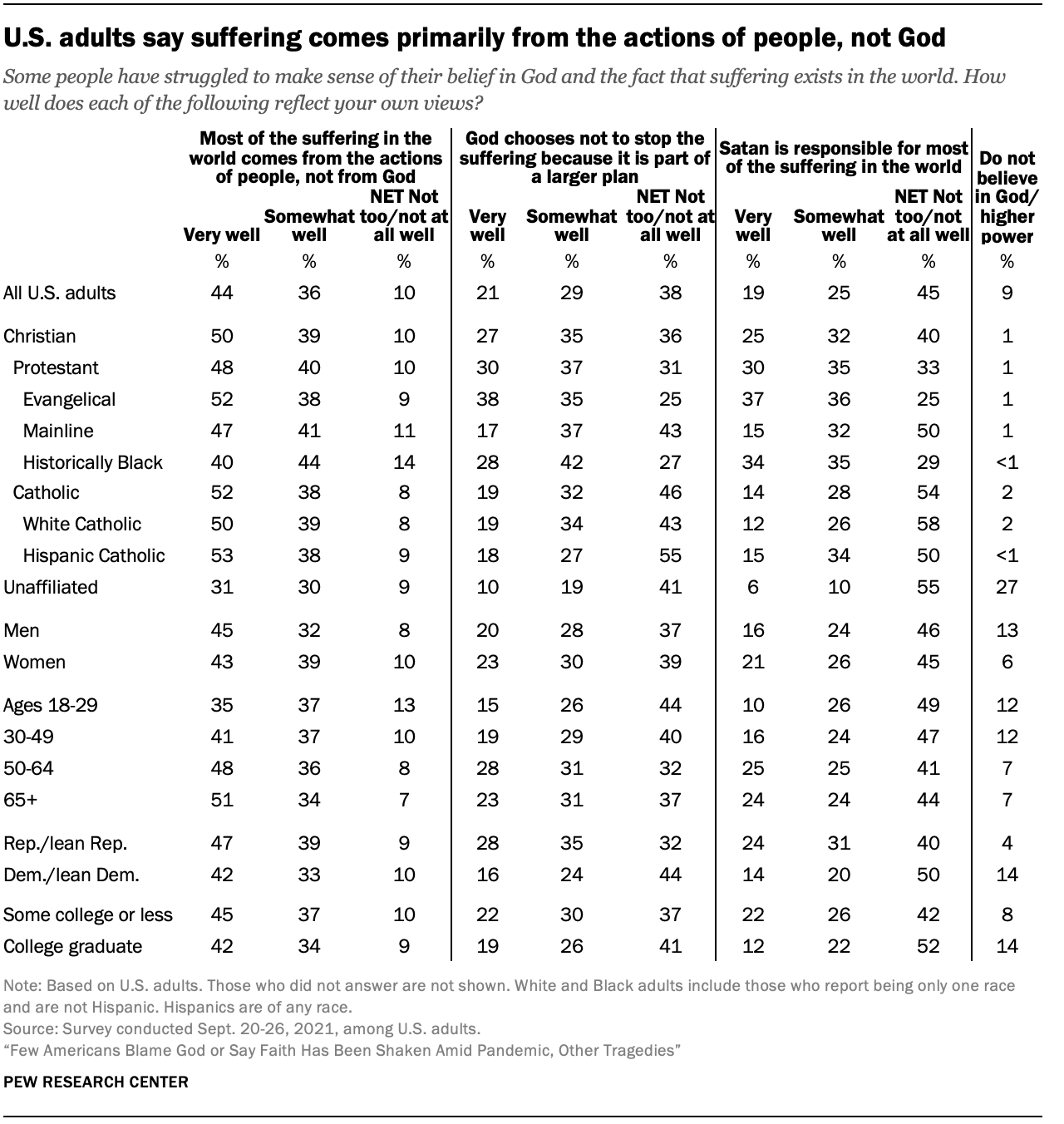

If the suffering in the world doesn’t make people doubt God’s existence, power or goodness, then how do people reconcile suffering with their beliefs about God? Most Americans largely place the blame for human suffering on people themselves. Eight-in-ten U.S. adults say the following statement describes their views at least somewhat well, including 44% who say it captures their perspective very well: “Most of the suffering in the world comes from the actions of people, not from God.”

Many also see human suffering as part of a larger plan. About half of U.S. adults endorse the idea that God chooses not to stop human suffering because it is part of a larger plan; 21% say this reflects their views very well, and an additional 29% say it is a somewhat accurate description of their feelings. Evangelical Protestants are more likely than other Americans to express strong agreement with the idea that human suffering is part of God’s larger plan.

Fewer than half of U.S. adults say that Satan is responsible for most of the human suffering in the world, including 19% who say this reflects their viewpoint very well and 25% who say it does somewhat well. Again, evangelical Protestants, along with members of the historically Black Protestant tradition, are especially inclined to hold these views about Satan, while Catholics are less likely to see the work of Satan in human suffering. And most religiously unaffiliated believers reject the idea that Satan is behind human suffering.

Americans with higher levels of education and young adults also are less likely than those with lower levels of education and older Americans to see Satan as primarily responsible for human suffering.

Relatively few say God directly influences everything that occurs

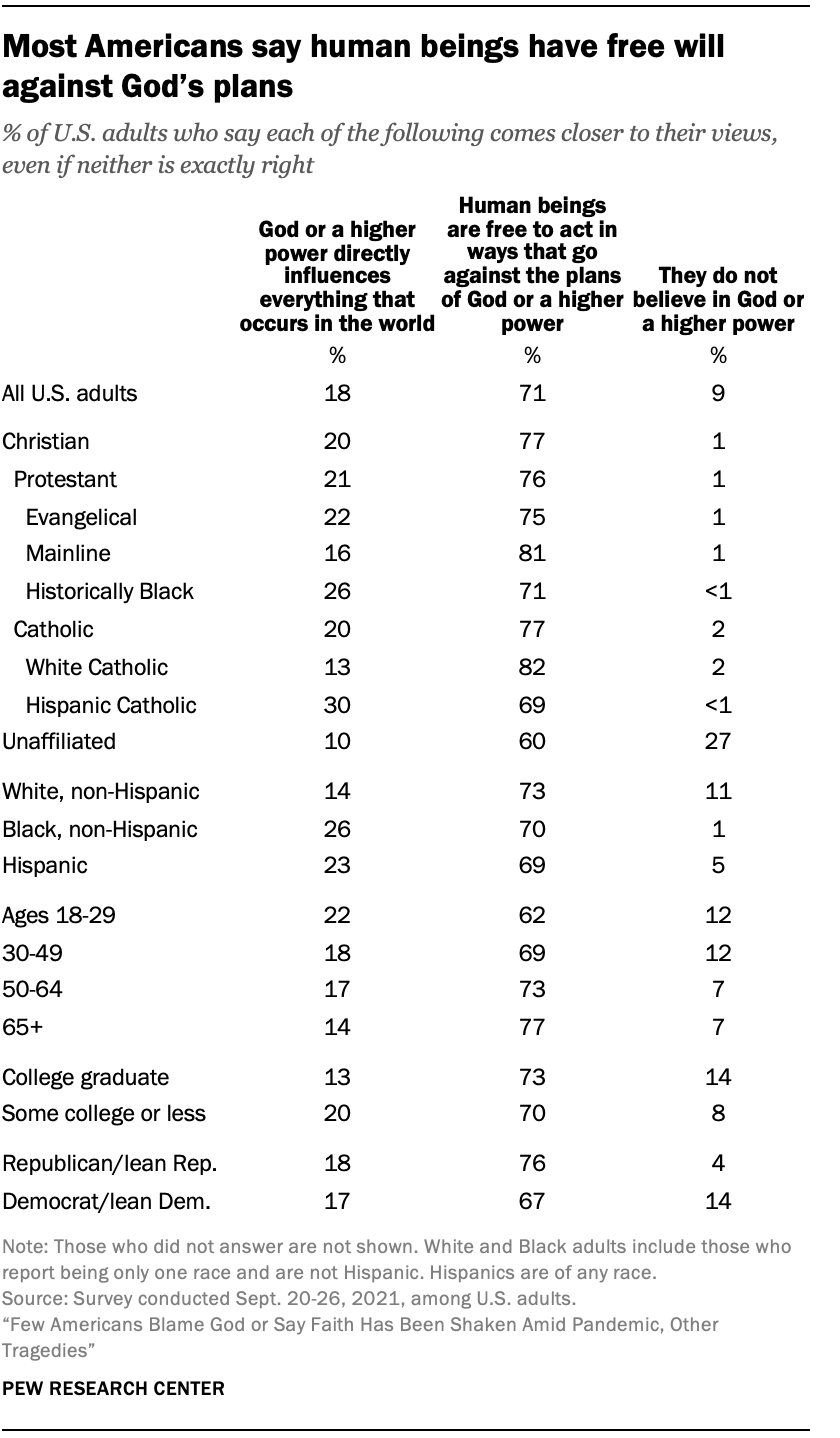

In a forced-choice question asking which of two positions comes closer to their views, Americans overwhelmingly say that human beings are “free to act in ways that go against the plans” of God or a higher power (71%), rather than that “God or a higher power directly influences everything” that occurs in the world (18%).

In a forced-choice question asking which of two positions comes closer to their views, Americans overwhelmingly say that human beings are “free to act in ways that go against the plans” of God or a higher power (71%), rather than that “God or a higher power directly influences everything” that occurs in the world (18%).

Black and Hispanic Americans are more likely than those who are White to say that God directly impacts everything that happens. In an overlapping pattern, people with college degrees are less inclined to believe this.

Strikingly, young adults (ages 18 to 29) are somewhat less likely than their elders to say that people have free will and can act contrary to God’s plans.