In the midst of a global pandemic that has killed millions and altered the lives of billions around the world, Pew Research Center conducted this survey to explore how Americans make sense of suffering and bad things happening to people. To achieve this, researchers reviewed existing literature and received guidance from academic experts to help develop a questionnaire. Additionally, the Center sought to explore views of the afterlife, including whether it exists and what it is like.

For this report, we surveyed 6,485 U.S. adults from Sept. 20 to 26, 2021. All respondents to the survey are part of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, religious affiliation and other categories. For more, see the ATP’s methodology and the methodology for this report.

The questions used in this report can be found here.

For centuries, philosophers and theologians have attempted to answer a vexing question: If there is a good and all-powerful God, then why is there so much suffering and evil in the world? From the biblical Book of Job to the 18th-century satirist Voltaire, the 20th-century Christian writer C.S. Lewis and the 1981 bestseller “When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” both great literature and popular culture repeatedly have tackled this “problem of evil.”

The question takes on added significance amid a global pandemic that has killed 5 million people and recent natural disasters including floods, hurricanes and wildfires. Against the backdrop of these events and others, most Americans say they have spent some time in the past year thinking about big questions like the meaning of life, whether there is any purpose to suffering, and why bad things happen to people, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Nearly a quarter of U.S. adults (23%) say they have mulled over these topics “a lot.”

In the new survey, the Center attempted for the first time to pose some of these philosophical questions to a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, finding that Americans largely blame random chance – along with people’s own actions and the way society is structured – for human suffering, while relatively few believers blame God or voice doubts about the existence of God for this reason.

Asking about the causes and meanings of suffering

There are many different ways to understand the causes and consequences of human suffering. People may bring some suffering on themselves, through poor choices or misguided actions. Other suffering might be caused by the way society is structured. Some may believe that suffering can arise as a punishment or a lesson from God or for some reason they cannot understand. Others may come to doubt God’s existence because they cannot reconcile the fact that suffering exists with the idea that there is a kind and all-powerful God in control of the universe. And of course, some suffering may occur randomly, for no reason at all.

To give respondents an opportunity to describe their beliefs on these matters, Pew Research Center asked about a wide variety of ways to make sense of the causes and consequences of suffering and gave respondents the opportunity to indicate whether each one describes their own views very well, somewhat well, not too well or not at all well. The questions were not designed to be mutually exclusive, and respondents were not asked to choose which one best explained their own views, but rather could effectively say “yes” to more than one (or even to all) of the survey’s questions on these topics.

Finally, while the survey touched on many possible reasons for suffering, there is no way for such a list to be exhaustive. So, in addition to the survey’s closed-ended questions, it also included an open-ended question in which respondents were invited to describe in their own words why they think terrible things sometimes happen to people through no fault of their own.

The survey gave respondents multiple opportunities to express their views on why terrible things happen – both in their own words in response to an open-ended question, and by reading through a list of possible explanations for suffering and indicating whether each statement describes their views very well, somewhat well, not too well or not at all well. The answers to these questions were not mutually exclusive; respondents could assent to more than one statement, and many did.

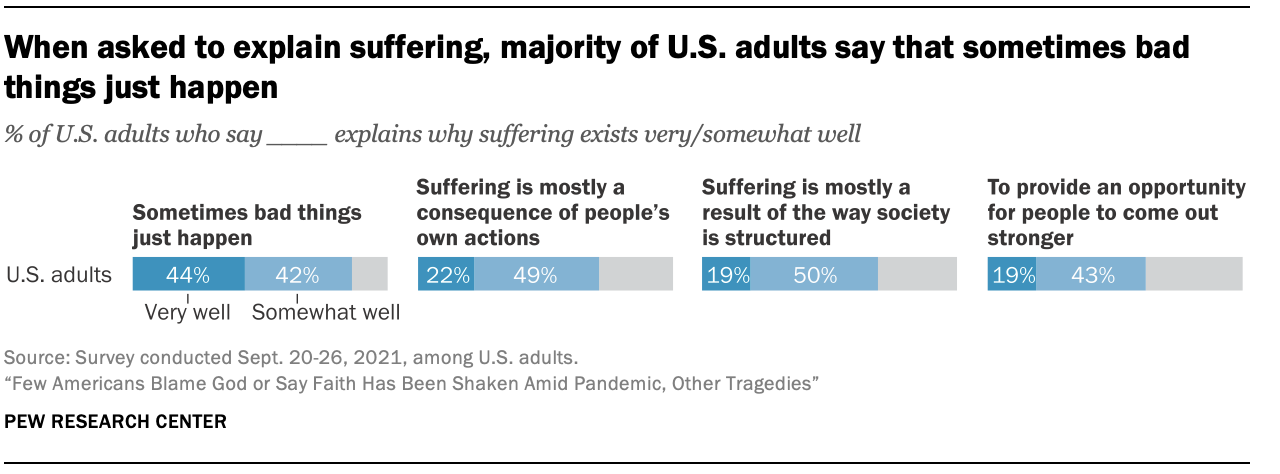

For example, the vast majority of U.S. adults ascribe suffering at least partly to random chance, saying that the phrase “sometimes bad things just happen” describes their views either very well (44%) or somewhat well (42%). Yet it is also quite common for Americans to feel that suffering does not happen in vain. More than half of U.S. adults (61%) think that suffering exists “to provide an opportunity for people to come out stronger.” And, in a separate set of questions about various religious or spiritual beliefs, two-thirds of Americans (68%) say that “everything in life happens for a reason.”

Many Americans lay some blame for the suffering that occurs in the world at the feet of individuals and societal institutions. Roughly seven-in-ten adults (71%) say the following statement describes their views at least somewhat well: “Suffering is mostly a consequence of people’s own actions.” A similar share of all adults (69%) express support for the statement “suffering is mostly a result of the way society is structured.”

For many people, views on suffering are connected to views about God. Religious thinkers have long attempted to reconcile the idea of an all-powerful, all-knowing and benevolent God as presented in the Abrahamic religious traditions – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – with the existence of tremendous evil in the world. Skeptics like the 18th-century British philosopher David Hume have argued that there is a logical contradiction, while writers from St. Augustine to the 20th-century American philosopher Alvin Plantinga have offered various defenses, such as that God has reasons for allowing evil that humans cannot understand, or that free will inevitably makes suffering and evil possible.

The new survey finds that nearly six-in-ten U.S. adults (58%) say they believe in God as described in the Bible, and an additional one-third (32%) believe there is some other higher power or spiritual force in the universe. The combined nine-in-ten Americans who believe in God or a higher power (91%) were asked a series of follow-up questions about the relationship between God and human suffering. (Those who do not believe in God or any higher power were not asked these questions.)

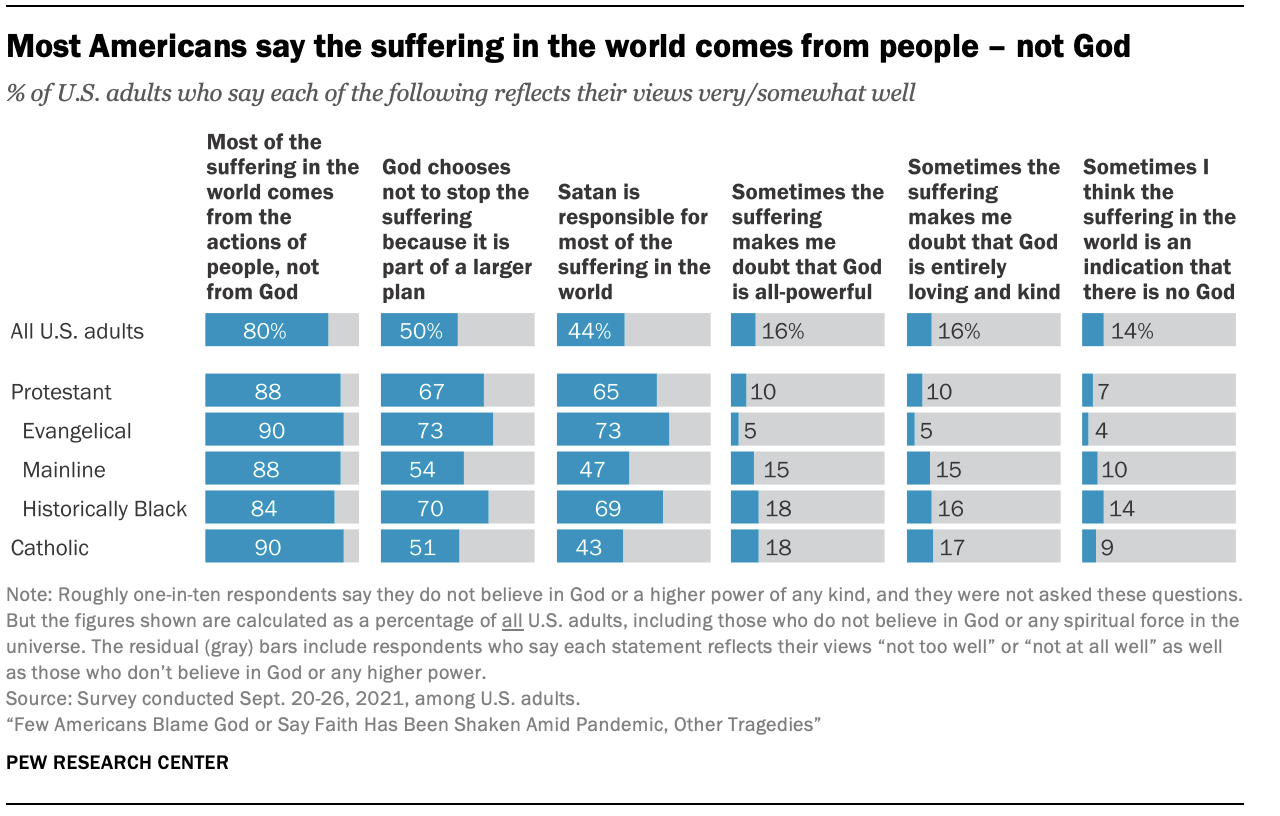

A large majority of U.S. adults (80%) are believers who say that most of the suffering in the world comes from people rather than from God. Relatedly, about seven-in-ten say that in general, human beings are free to act in ways that go against the plans of God or a higher power. At the same time, half of all U.S. adults (or 56% of believers) also endorse the idea that God chooses “not to stop the suffering in the world because it is part of a larger plan.”

Meanwhile, 44% of all U.S. adults (48% of believers) say the notion that “Satan is responsible for most of the suffering in the world” reflects their views either “very well” or “somewhat well,” with Protestants in the evangelical and historically Black traditions especially likely to take this position.

By comparison, relatively few Americans seem to question their religious beliefs because human suffering exists. For instance, 14% of U.S. adults overall (or 15% of believers) affirm that “sometimes I think the suffering in the world is an indication that there is no God.” Results are similar on questions about whether suffering has caused Americans to doubt that God is all-powerful or entirely loving.

In addition, fewer than one-in-five U.S. adults are believers who say they often (3%) or sometimes (14%) get angry with God “for allowing so much suffering.” And relatively small numbers view the suffering in the world as a punishment from God: Just 4% of U.S. adults overall are believers who say “all or most” suffering is a punishment from God, and 18% say “some” of it is. The remainder say that “only a little” (22%) or “none at all” (46%) of the suffering in the world is punishment from God, or they don’t believe in God or any higher power (9%).

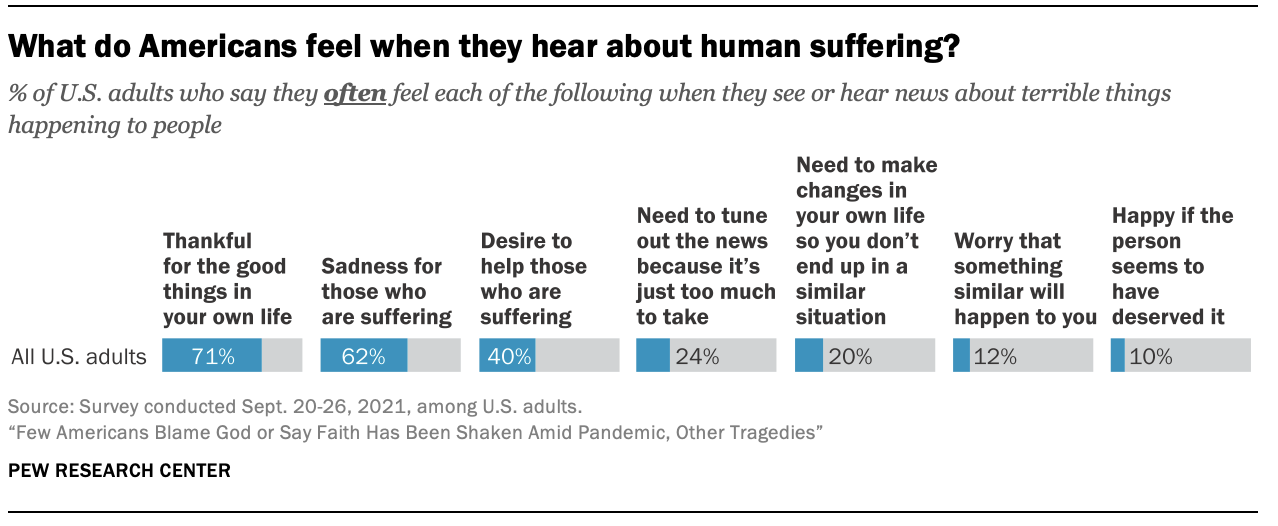

Majorities of U.S. adults say that when they see or hear news about terrible things happening to people, they often feel gratitude for the good things in their own lives and sadness for those who are suffering. About one-quarter say they feel the need to tune out the bad news “because it’s just too much to take,” and one-in-ten admit to schadenfreude, or feeling happy “if the person [who is suffering] seems to have deserved it.”

These are among the key findings from a new Pew Research Center survey of 6,485 U.S. adults, conducted on the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP). Although the survey was conducted among Americans of all religious backgrounds – including Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, Mormons and more – it did not obtain enough respondents from these smaller religious groups to report separately on their views.

The new survey also asked about views of the afterlife, finding that many Americans believe in an afterlife where suffering either ends entirely or continues in perpetuity.

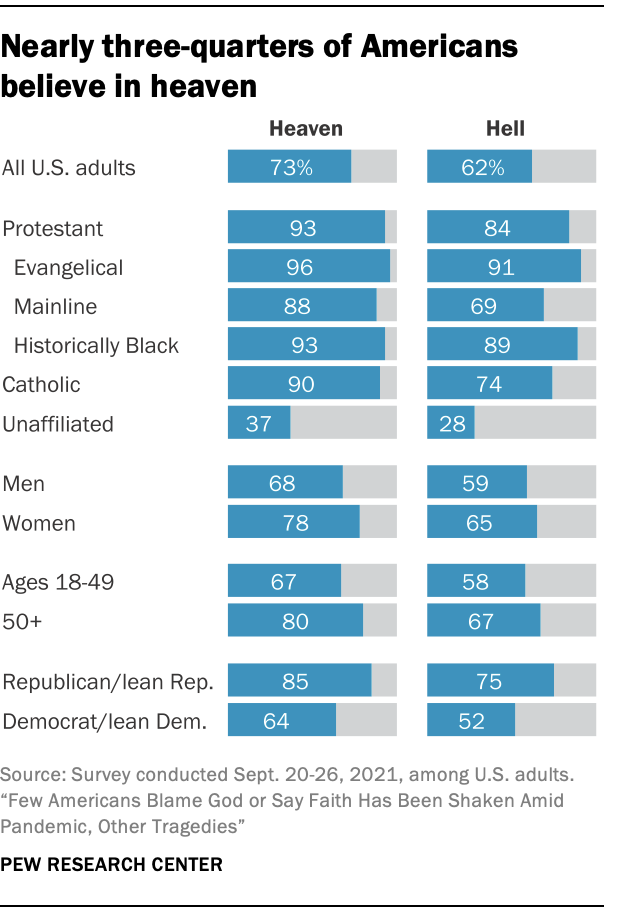

Nearly three-quarters of all U.S. adults (73%) say they believe in heaven, while a smaller share – but still a majority (62%) – believe in hell. Both figures are similar to what the Center found when it last asked these questions, in 2017. Among Christians, overwhelming majorities of all major subgroups express belief in heaven, but Protestants who belong to the evangelical and historically Black Protestant traditions are more likely than mainline Protestants and Catholics to express belief in hell. Meanwhile, roughly a quarter of U.S. adults say they believe in neither heaven nor hell, including 7% who believe in some other kind of afterlife and 17% who do not believe in any afterlife at all.

Nearly three-quarters of all U.S. adults (73%) say they believe in heaven, while a smaller share – but still a majority (62%) – believe in hell. Both figures are similar to what the Center found when it last asked these questions, in 2017. Among Christians, overwhelming majorities of all major subgroups express belief in heaven, but Protestants who belong to the evangelical and historically Black Protestant traditions are more likely than mainline Protestants and Catholics to express belief in hell. Meanwhile, roughly a quarter of U.S. adults say they believe in neither heaven nor hell, including 7% who believe in some other kind of afterlife and 17% who do not believe in any afterlife at all.

Americans who expressed belief in heaven and hell were asked several questions about what they think those places are like. The vast majority of those who believe in heaven – which is most U.S. adults – say they believe heaven is “definitely” or “probably” a place where people are free from suffering, are reunited with loved ones who died previously, can meet God, and have perfectly healthy bodies. And about half of all Americans (i.e., most of those who believe in hell) view hell as a place where people experience psychological and physical suffering and become aware of the suffering they created in the world. A similar share says that people in hell cannot have a relationship with God.

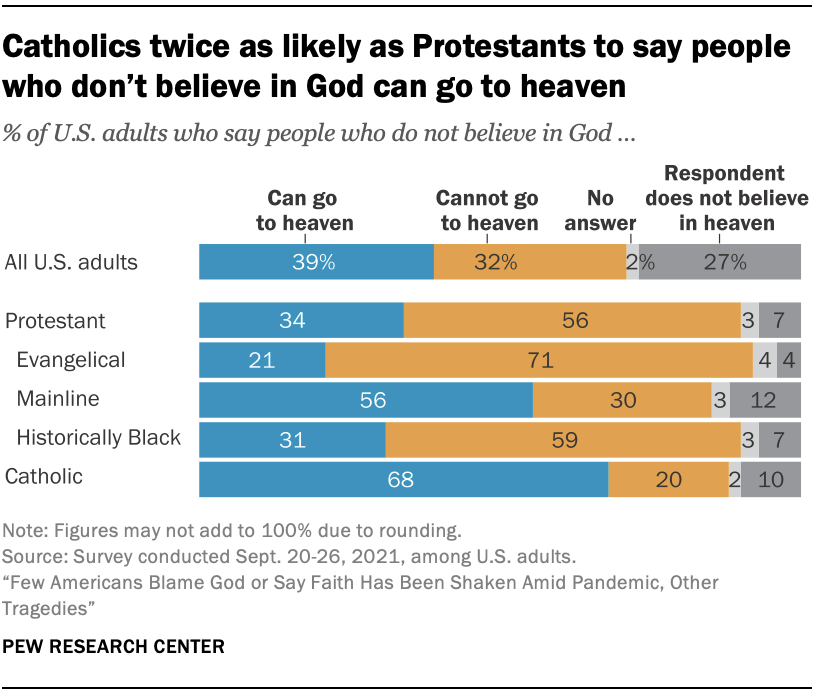

In addition to these questions about the nature of heaven, respondents who expressed belief in heaven were asked about who they think will be allowed to go there. Four-in-ten U.S. adults (39%) say they think people who do not believe in God can enter heaven, compared with about one-third (32%) who say only believers can gain access. (Again, 27% of adults do not believe in heaven at all.) Catholics are far more likely than Protestants to say that people who do not believe in God can go to heaven (68% vs. 34%). Evangelical Protestants are especially restrictive in their view, with just 21% saying that people who do not believe in God can get to heaven.

In addition to these questions about the nature of heaven, respondents who expressed belief in heaven were asked about who they think will be allowed to go there. Four-in-ten U.S. adults (39%) say they think people who do not believe in God can enter heaven, compared with about one-third (32%) who say only believers can gain access. (Again, 27% of adults do not believe in heaven at all.) Catholics are far more likely than Protestants to say that people who do not believe in God can go to heaven (68% vs. 34%). Evangelical Protestants are especially restrictive in their view, with just 21% saying that people who do not believe in God can get to heaven.

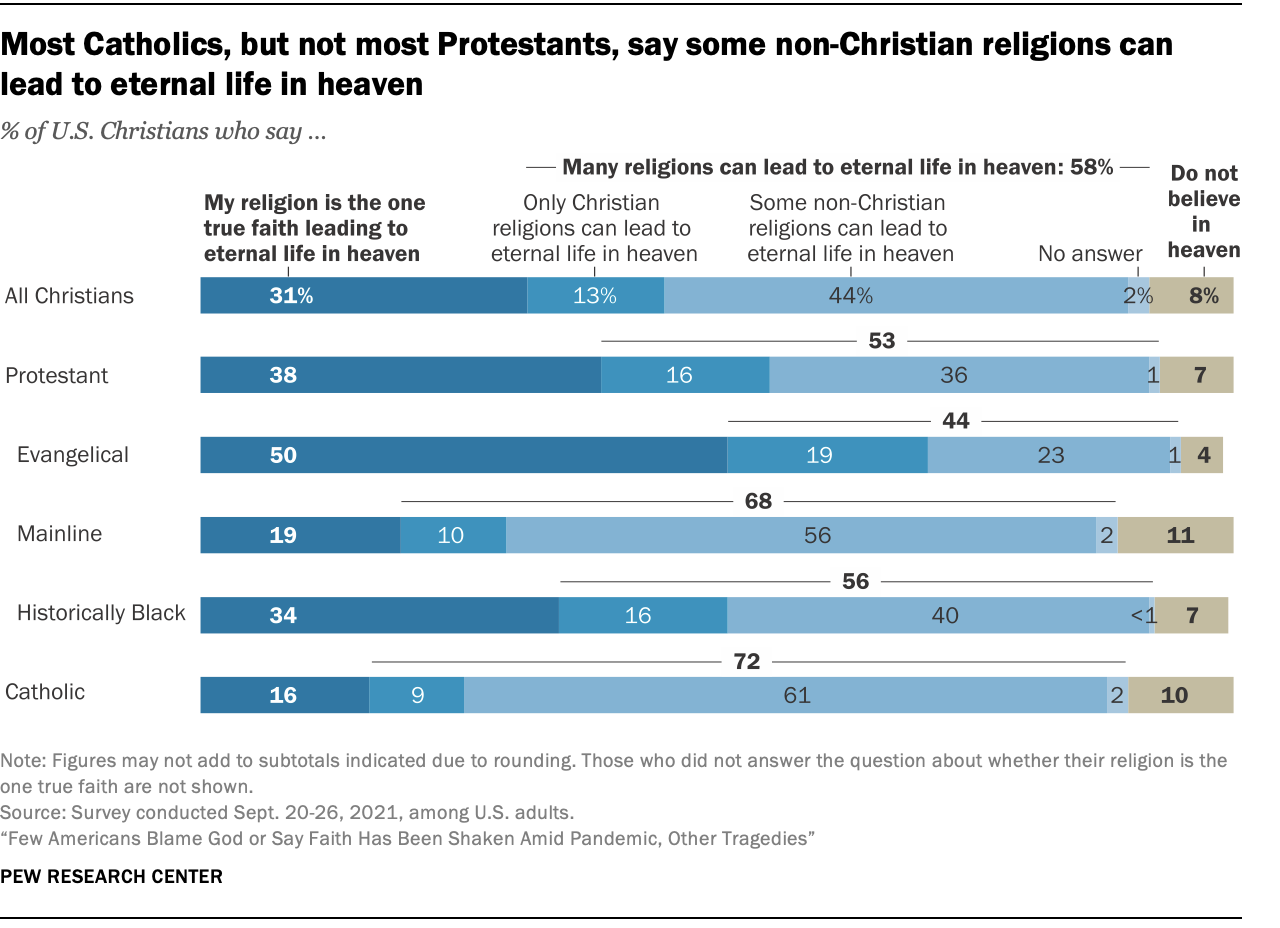

There also is wide variance among Christians on the question of whether “many religions” can lead to eternal life in heaven or if their religion is the “one true faith” leading to heaven. Protestants are more than twice as likely as Catholics to say that their faith is the one true faith leading to eternal life in heaven (38% vs. 16%), with half of evangelicals expressing this view. On the other hand, 44% of evangelical Protestants say that many religions can lead to eternal life in heaven, though they are split on whether this reward is granted only to members of other branches of Christianity (19%) or if followers of some non-Christian religions also can go to heaven (23%).

Other findings from the survey include:

- One-third of all U.S. adults say they believe in reincarnation, the idea that people will be reborn again and again in this world. Unlike the pattern on many religious beliefs – including belief in heaven and hell – younger adults (under age 50) are more likely than their elders to report holding this belief. Black and Hispanic adults also are more likely than White adults to say they believe in reincarnation.

- A larger share (44%) expresses belief in fate – the idea that the course of their life is predetermined – including roughly two-thirds of Black Americans (65%) who hold this view.

- More than eight-in-ten U.S. adults say they believe things can happen that cannot be explained by science or natural causes. And, in response to more specific questions, majorities say it is possible to feel the presence of someone who has died, to receive a direct revelation from God, to receive a definite answer to a prayer request and to have a near-death experience in which a person’s spirit actually leaves their body.

The remainder of this report explores the survey findings in more detail.