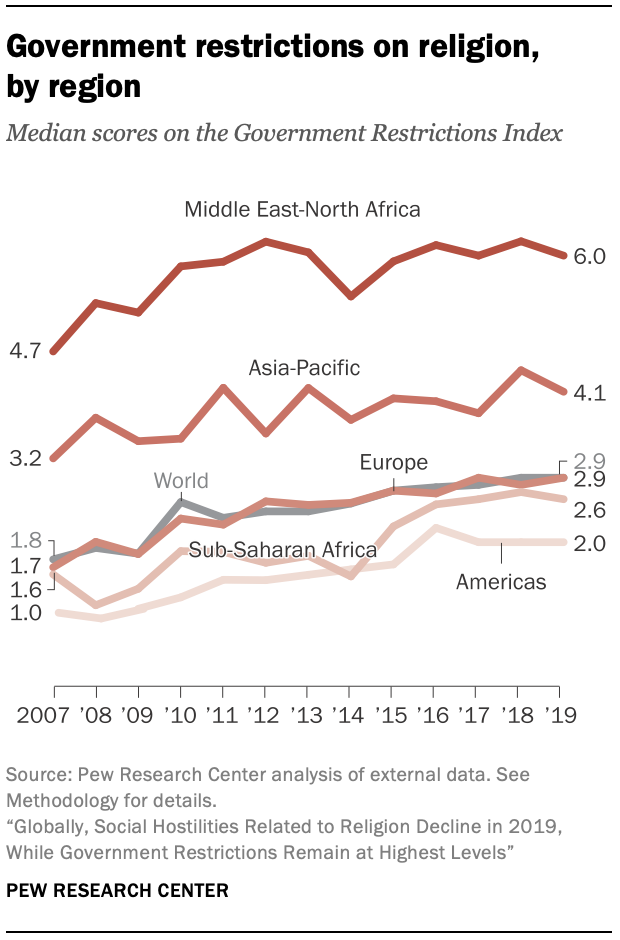

Government restrictions by region

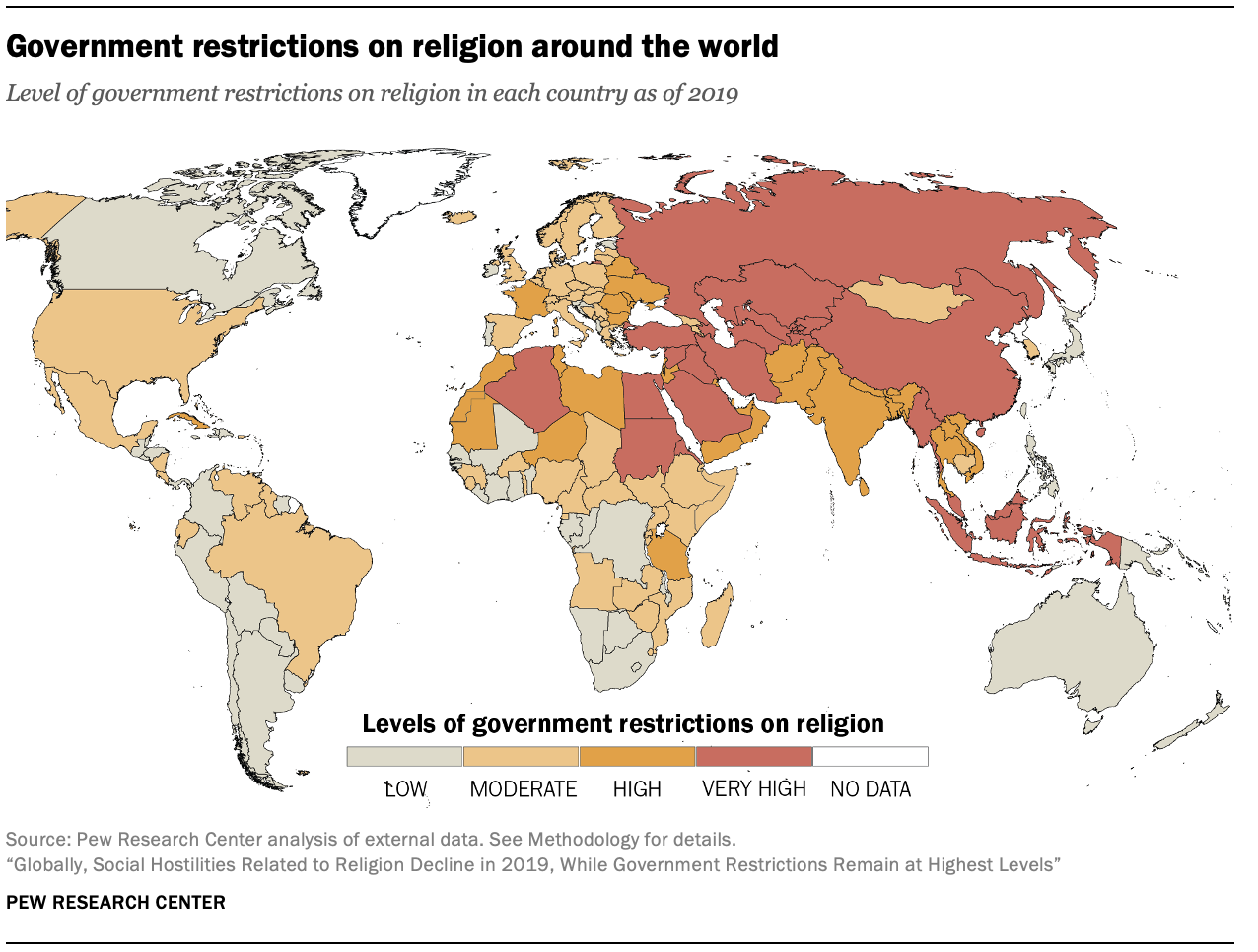

In 2019, the median Government Restrictions Index (GRI) score of the 198 countries and territories in this study remained stable at 2.9, staying at its highest level since Pew Research Center began tracking these measures in 2007 (see Overview). The median score on the index decreased in three of the five regions examined – Asia-Pacific, Middle East-North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa – while increasing slightly in Europe and remaining about the same in the Americas.52

In 2019, the median Government Restrictions Index (GRI) score of the 198 countries and territories in this study remained stable at 2.9, staying at its highest level since Pew Research Center began tracking these measures in 2007 (see Overview). The median score on the index decreased in three of the five regions examined – Asia-Pacific, Middle East-North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa – while increasing slightly in Europe and remaining about the same in the Americas.52

Although the Middle East-North Africa region experienced a small decline in its median GRI score, from 6.2 in 2018 to 6.0 in 2019, it continued to have the highest GRI score of all the regions studied. All 20 countries and territories in the region officially favored a religious group: Islam in 19, and Judaism in one (Israel). In addition, governments in every country in the region interfered in worship and harassed religious groups. In more than half of those countries, governments used physical violence against minority groups (12 countries) and formally banned at least one religious group (11 countries). For example, in Egypt, where Islam is the state religion, the law does not formally recognize Jehovah’s Witnesses or members of the Baha’i faith, barring them from owning houses of worship, holding bank accounts and importing religious literature.53

In the Asia-Pacific region, the median score on the GRI fell from 4.4 in 2018 to 4.1 in 2019, although it is still higher than it was in 2017 (3.8). The decline in 2019 was due in part to slightly fewer governments in the region using force against religious groups or attempting to remove a religious group from their country. (See GRI.Q.19 and GRI.Q.17 in Appendix D for more information on these measures.) Still, government force against religious groups occurred in more than half the countries in the region (28 of 50) in 2019, the second-highest share of any region studied.

In China, various sources estimated that more than a million Uyghur Muslims, ethnic Kazakhs, members of other Muslim groups and Uyghur Christians were being arbitrarily detained by government authorities in internment camps in Xinjiang province. While imprisoned, these individuals were subject to “forced disappearance, political indoctrination, torture,” and psychological and physical abuse, “including forced sterilization and sexual abuse, forced labor, and prolonged detention without trial because of their religion and ethnicity,” according to the U.S. Department of State. In addition, about half a million children in Xinjiang province were reported to have been separated from their families and relocated to boarding schools, where they were indoctrinated in the country’s dominant ethnic Han culture in an effort to stem the influence of religion from their homes.54

Harassment or intimidation of religious groups and interference in worship remained widespread in the rest of the Asia-Pacific region as well, with such restrictions occurring in at least 70% of countries in the region. In Vietnam, for instance, Catholic bishops and priests reported that they were harassed by authorities who disrupted or prevented their services and gatherings. In April, a Catholic community in the country’s Lai Chau province was denied permission to hold Easter Mass.55

Europe was the only region that had a small increase in its median level of government restrictions, ticking up from 2.8 in 2018 to 2.9 in 2019. According to sources used for this study, authorities in 24 of 45 European countries failed to protect religious groups from discrimination or abuse, up from 16 countries in 2018. For example, in Moldova, police initially refused to investigate a report that a Jehovah’s Witness was physically assaulted for preaching in a village, and when the authorities did look into the matter, they fined the Jehovah’s Witness for “insulting religious feelings” of a local Orthodox priest. (They also fined the priest, who had organized a harassment campaign against Jehovah’s Witnesses preaching in the area, for “obstructing religious freedom.”56) Meanwhile, in the Netherlands, there were reports that people who brought claims of anti-Semitic harassment or other incidents of discrimination were not taken seriously by the police or were discouraged from filing charges. In response to these reports, the Dutch parliament passed a nonbinding resolution in 2019 that called for special detectives to address cases of anti-Semitism and other incidents of discrimination.57

There also was a small uptick in the number of European countries where governments used force against religious groups, from 17 in 2018 to 19 in 2019, though most European countries had fewer than 10 reported cases of such incidents. Russia had the highest number of cases in the region; its government continued to enforce a 2017 ban on Jehovah’s Witnesses, labeling their activities as “extremist” and raiding nearly 500 homes of Jehovah’s Witnesses in 2019, compared with under 300 in 2018, according to Human Rights Watch.58

In sub-Saharan Africa, the median GRI score in the region’s 48 countries declined from 2.7 in 2018 to 2.6 in 2019, due in part to slightly fewer reports of government limits on public preaching, religious conversions and foreign missionaries. At the same time, more governments in sub-Saharan Africa interfered in worship and harassed or intimidated religious groups, including by force. In Comoros, for example, authorities in 2019 arrested at least 30 Shiite Muslims for group worship that was “not conforming to the state-endorsed version of Sunni Islam.”59 And in Togo, authorities suspended worship at five churches for failing to respond to noise complaints.60

The median government restrictions score for the Americas remained at 2.0 in 2019, the lowest of all regions studied.

Social hostilities by region

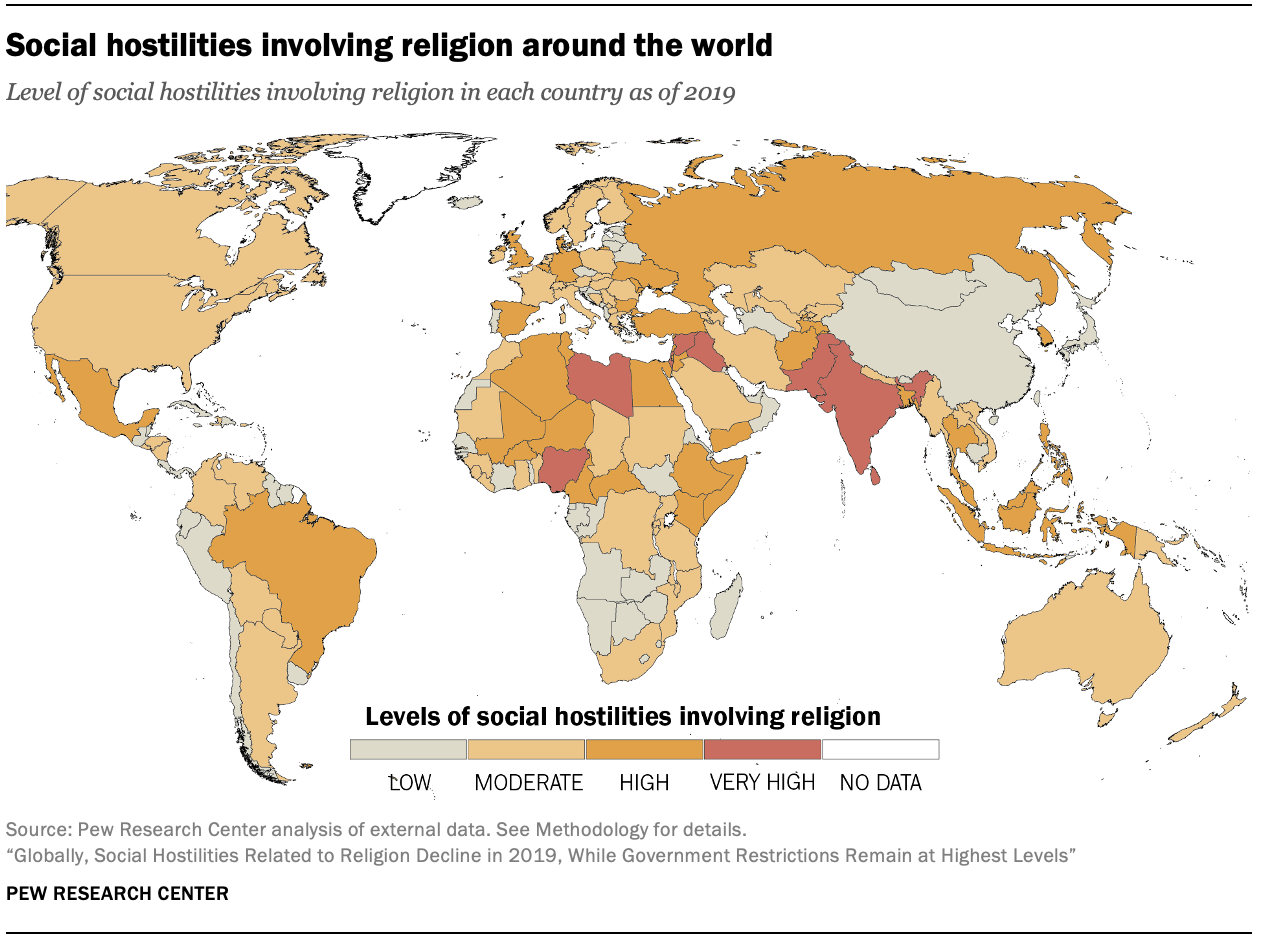

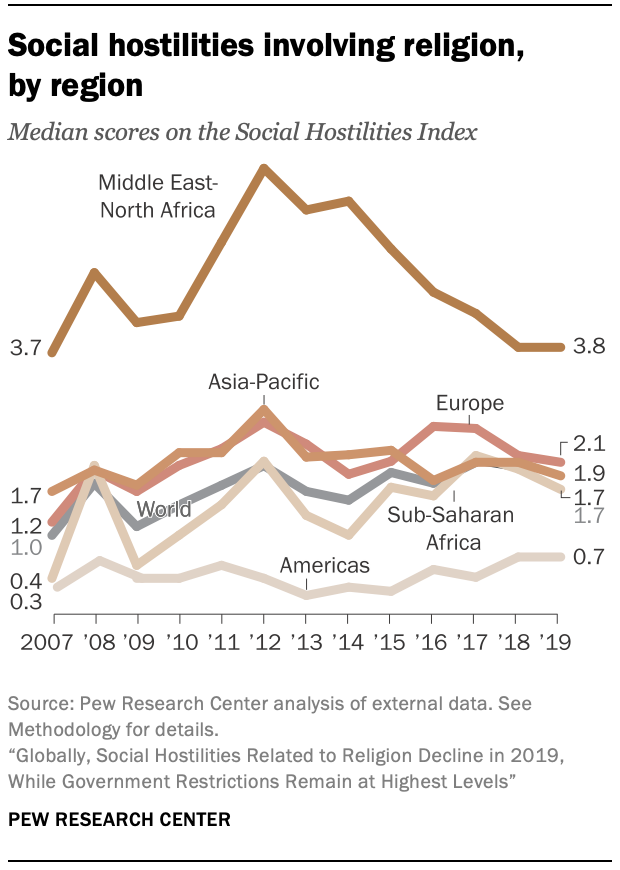

In 2019, the global median score on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) fell to a five-year low of 1.7. The Asia-Pacific region, Europe and sub-Saharan Africa all experienced declines on this index, while the scores for the Americas and the Middle East-North Africa region remained stable.

In 2019, the global median score on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) fell to a five-year low of 1.7. The Asia-Pacific region, Europe and sub-Saharan Africa all experienced declines on this index, while the scores for the Americas and the Middle East-North Africa region remained stable.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the median score on the Social Hostilities Index fell from 2.0 in 2018 to 1.7 in 2019. This was partly because fewer countries reported hostilities over conversions and fewer reported activities by organized groups that used force or coercion in an attempt to dominate public life with their perspectives on religion. (See SHI.Q.7 in Appendix D for more information on this measure and all other measures in each index of this study.)

The median level of social hostilities also decreased in the Asia-Pacific region (from 2.1 in 2018 to 1.9 in 2019), and in Europe (from 2.2 to 2.1). In both regions, there were fewer countries with groups that tried to prevent other religious groups from operating, fewer countries with religion-related terrorist incidents and fewer countries with mob violence related to religion.

Meanwhile, the median score for the Middle East-North Africa region stayed at 3.8 for the second straight year, near its lowest point (3.7 in 2007, the first year of the study). The median SHI score for the Americas also remained stable at 0.7 and was the lowest score among all regions in the study.