Every two years, Pew Research Center publishes a report on the religious affiliation of members of the incoming Congress. This report is the seventh in the series, which started with the 111th Congress that began in 2009.

Data on members of Congress comes from CQ Roll Call, which surveys members about their demographic characteristics, including religious affiliation. Pew Research Center researchers then code the data so that Congress can be compared with U.S. adults overall. For example, members of Congress who tell CQ Roll Call they are “Southern Baptists” are coded as “Baptists” – a broader category (including Southern Baptists as well as other Baptists) used for analysis of the general public.

Data in this report covers members of Congress sworn in on Jan. 3, 2021. One contested election, in New York’s 22nd District, was uncalled by the start of the new Congress. Congressman-elect Luke J. Letlow of Louisiana’s 5th District died before the swearing-in; his seat will go unfilled until a March special election. One representative, Mariannette Miller-Meeks of Iowa, was sworn in provisionally on Jan. 3; she is included in this analysis. In addition, both of Georgia’s Senate seats were subject to runoff elections set to take place Jan. 5, 2021. Therefore, this analysis includes 531 members of Congress, rather than 535.

Data for all U.S. adults comes from aggregated Pew Research Center political surveys conducted on the telephone from January 2018 through July 2019 and summarized in the report “In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace.” Figures for Protestant subgroups and Unitarians come from the Center’s 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study, conducted June 4 to Sept. 30, 2014, among more than 35,000 Americans. For more information about how Pew Research Center measures the religious composition of the U.S., see here.

When it comes to religious affiliation, the 117th U.S. Congress looks similar to the previous Congress but quite different from Americans overall.

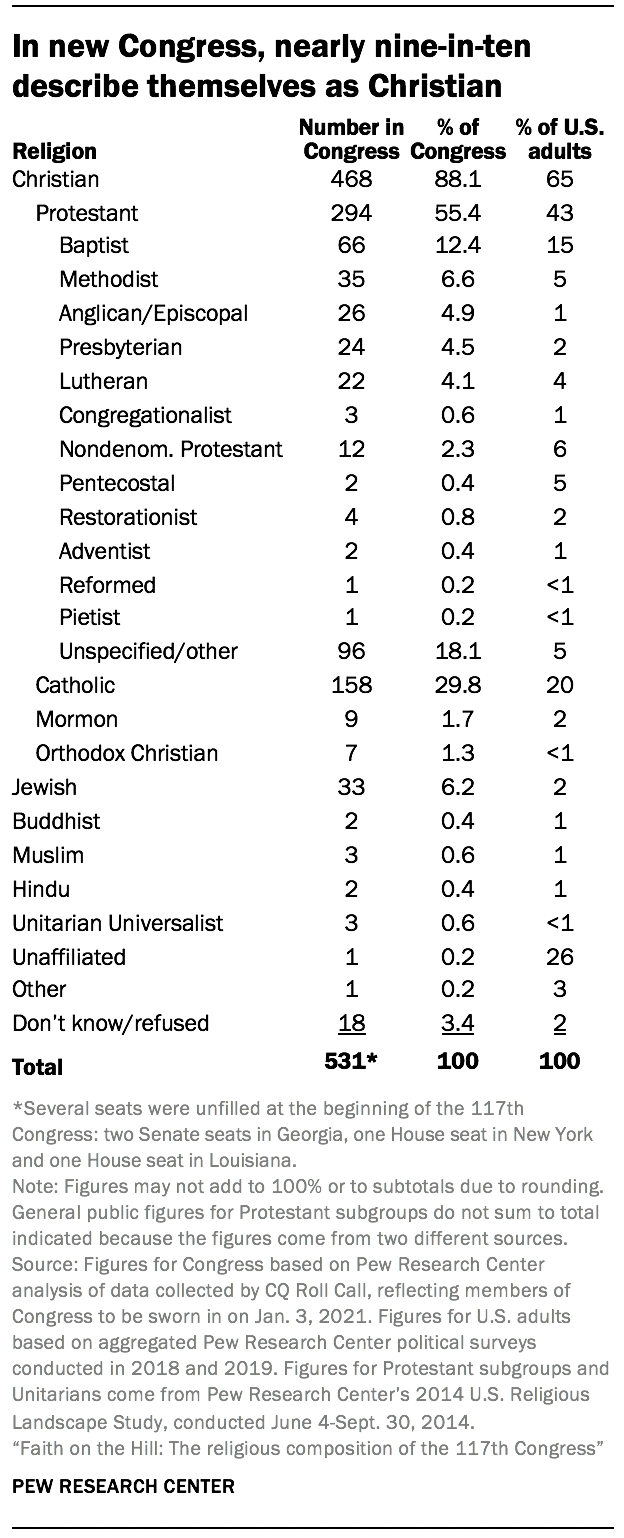

While about a quarter (26%) of U.S. adults are religiously unaffiliated – describing themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” – just one member of the new Congress (Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz.) identifies as religiously unaffiliated (0.2%).

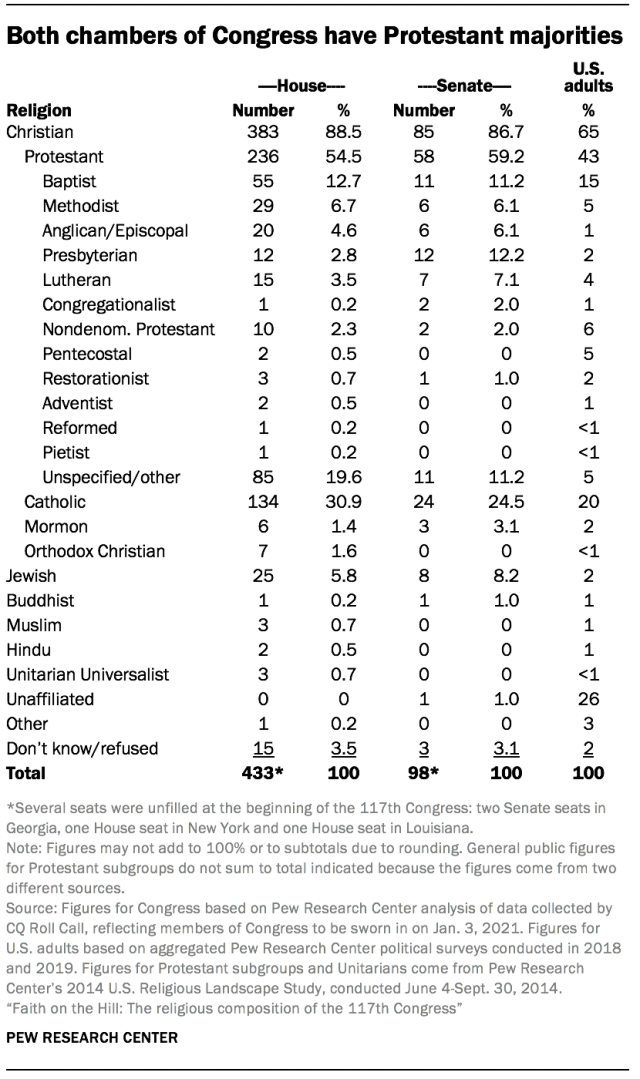

Nearly nine-in-ten members of Congress identify as Christian (88%), compared with two-thirds of the general public (65%). Congress is both more heavily Protestant (55% vs. 43%) and more heavily Catholic (30% vs. 20%) than the U.S. adult population overall.

Members of Congress also are older, on average, than U.S. adults overall. At the start of the 116th Congress, the average representative was 57.6 years old, and the average senator was 62.9 years old.1 Pew Research Center surveys have found that adults in that age range are more likely to be Christian than the general public (74% of Americans ages 50 to 64 are Christian, compared with 65% of all Americans ages 18 and older). Still, Congress is more heavily Christian even than U.S. adults ages 50 to 64, by a margin of 14 percentage points.2

Over the last several Congresses, there has been a marked increase in the share of members who identify themselves simply as Protestants or as Christians without further specifying a denomination. There are now 96 members of Congress in this category (18%). In the 111th Congress, the first for which Pew Research Center analyzed the religious affiliation of members of Congress, 39 members described themselves this way (7%). Meanwhile, the share of all U.S. adults in this category has held relatively steady.

Over the same period, the total number of Protestants in Congress has remained relatively stable: There were 295 Protestants in the 111th Congress, and there are 294 today. The increase in Protestants who do not specify a denomination has corresponded with a decrease in members who do identify with denominational families, such as Presbyterians, Episcopalians and Methodists.

Still, members of those three Protestant subgroups remain overrepresented in Congress compared with their share in the general public, while some other groups are underrepresented – including Pentecostals (0.4% of Congress vs. 5% of all U.S. adults), nondenominational Protestants (2% vs. 6%) and Baptists (12% vs. 15%).3

Jewish members also make up a larger share of Congress than they do of the general public (6% vs. 2%). The shares of most other non-Christian groups analyzed in this report (Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus and Unitarian Universalists) more closely match their percentages in the general public.

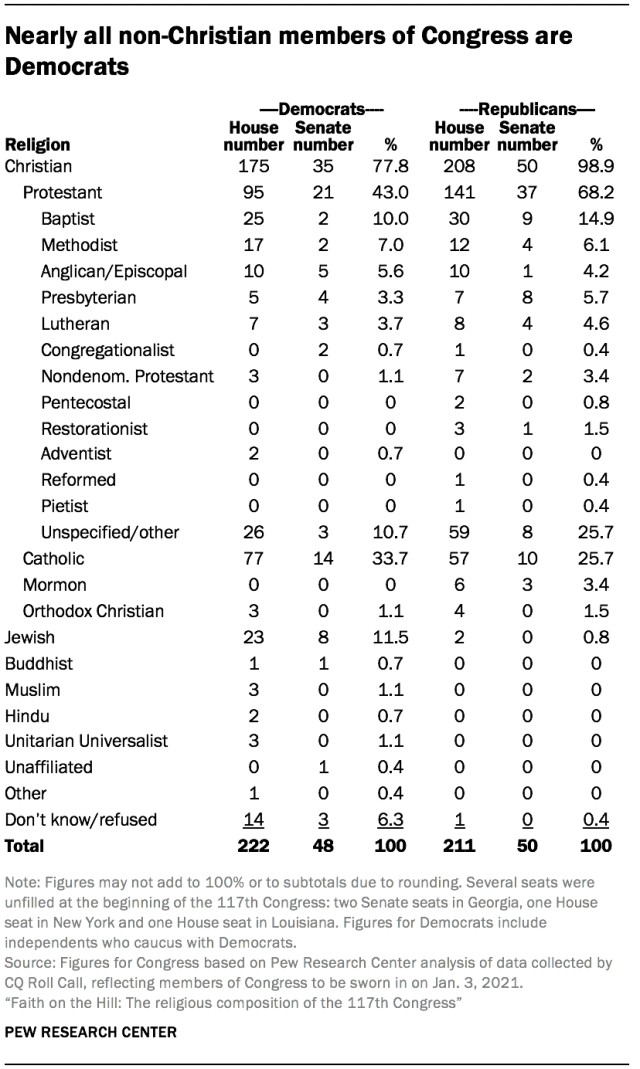

Nearly all non-Christian members of Congress are Democrats. Just three of the 261 Republicans who were sworn in on Jan. 3 (1%) do not identify as Christian; two are Jewish, and one declined to state a religious affiliation.

These are some of the key findings of an analysis by Pew Research Center of CQ Roll Call data on the religious affiliations of members of Congress, gathered through questionnaires and follow-up phone calls to candidates’ and members’ offices.4 The CQ questionnaire asks members what religious group, if any, they belong to. It does not attempt to measure their religious beliefs or practices. The Pew Research Center analysis compares the religious affiliations of members of Congress with the Center’s survey data on the U.S. public.

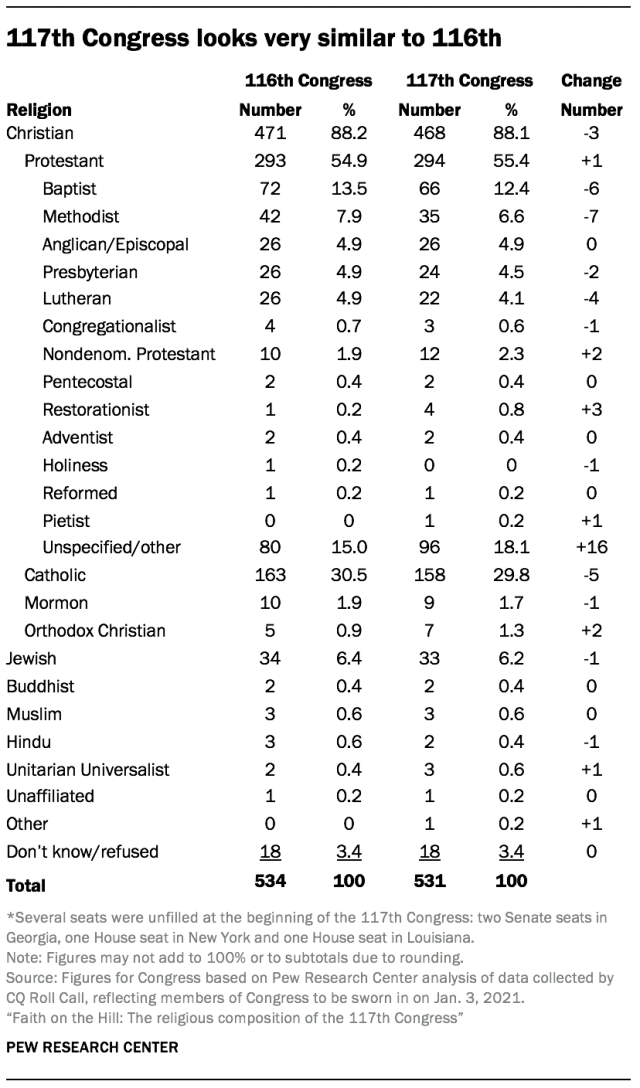

Little change between 116th and 117th Congresses for most religious groups

The overall composition of the new Congress is similar to that of the previous Congress – in part because 464 of the 531 members of the 117th Congress (87%) are returning members.

Methodists saw the largest loss – seven seats – followed closely by Baptists (six seats) and Catholics (five seats). There also are four fewer Lutherans in the 117th Congress than there were in the 116th. By contrast, Protestants who do not specify a denomination are up substantially, gaining 16 seats in the 117th Congress after also gaining 16 seats two years ago, when the 116th took office. Protestants in the Restorationist family also gained three seats (all members of Congress in this category identify with the Churches of Christ).5

In total, there currently are three fewer Christians in the new Congress than there were in the previous Congress, although this gap is all but certain to narrow once three of the four open seats are filled. Five of the six candidates in the uncalled or outstanding races identify as Christians; Jon Ossoff, a Democrat running for Senate in Georgia, is Jewish.6

When it comes to the 63 members of Congress who are not Christian, a slim majority (33) are Jewish, a number that has held relatively steady over the past several Congresses.

The next largest non-Christian group is made up of those who declined to specify a religious affiliation. There are 18 people in this category in the 117th Congress, the same as in the 116th, which had seen an increase of eight members in this group.

The three Muslim representatives from the 116th Congress return for the 117th: Reps. André Carson, D-Ind.; Ilhan Omar, D-Minn.; and Rashida Tlaib, D-Mich. Similarly, both Buddhists from the previous Congress return: Georgia Democratic Rep. Hank Johnson and Hawaii Democratic Sen. Mazie K. Hirono.

Unitarian Universalists gained one seat, as Rep. Deborah K. Ross, D-N.C., joins California Democratic Reps. Ami Bera and Judy Chu.

There are now two Hindus in Congress – Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., and Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, D-Ill., both returning members. Former Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, who served in the 115th and 116th Congresses, ran for president in 2020 and withdrew her reelection bid for her House seat. She is replaced by Kai Kahele, who declined to specify a religious affiliation.

One member, California Democratic Rep. Jared Huffman, describes himself as a humanist. He is listed in the “other” category. Fewer than three-tenths of 1% of U.S. adults specifically call themselves humanists.

Sinema is the only member of the 117th Congress who identifies as religiously unaffiliated. Both Sinema and Huffman have said they do not consider themselves atheists.7

Differences by chamber

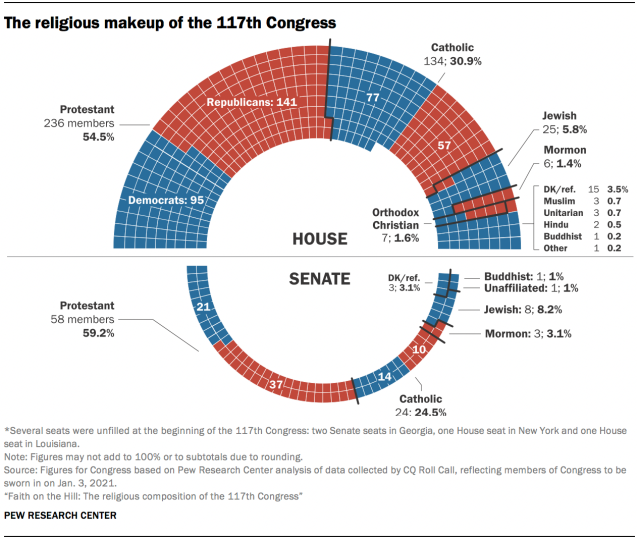

Most members of the House and Senate are Christians, with the House just slightly more Christian than the Senate (88% vs. 87%). And both chambers have a Protestant majority – 55% of representatives are Protestant, as are 59% of senators.

Within Protestantism, the largest differences are in Presbyterians (3% in the House vs. 12% in the Senate) and Protestants who do not specify a denomination (20% in the House, 11% in the Senate).

Catholics make up a larger share in the House (31%) than in the Senate (24%).

The Senate, meanwhile, has a higher share of Jewish (8% vs. 6%) and Mormon (3% vs. 1%) members than the House does.

All of the Muslims, Hindus and Unitarian Universalists in Congress are in the House, while there is one Buddhist in each chamber.

The sole religiously unaffiliated member of Congress (Sinema) is in the Senate, and the only member in the “other” category (Huffman) is in the House.

Differences by party

Fully 99% of Republicans in Congress identify as Christians. There are two Jewish Republicans in the House, Reps. Lee Zeldin of New York and David Kustoff of Tennessee. New York Rep. Chris Jacobs declined to specify a religious affiliation. All other Republicans in the 117th Congress identify as Christian in some way.

Most Republican members of Congress identify as Protestants (68%). The largest Protestant groups are Baptists (15%), Methodists (6%), Presbyterians (6%), Lutherans (5%) and Episcopalians (4%). However, 26% of Republicans are Protestants who do not specify a denomination – up from 20% in the previous Congress. There are 15 Republican freshmen in this category, compared with three Democratic newcomers.

Now that Democratic Sen. Tom Udall of New Mexico has retired, all nine members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (sometimes called Mormons) in Congress are Republicans.8

Democrats in Congress also are heavily Christian – much more than U.S. adults overall (78% vs. 65%).9 But the share of Democrats who identify as Christian is 21 percentage points lower than among Republicans (99%). Democrats are much less likely than Republicans to identify as Protestant (43% vs. 68%). Conversely, Catholics make up a higher share among Democrats than they do among Republicans (34% vs. 26%).

Among Democrats, 11% are Jewish, and 6% did not specify a religious affiliation. All of the Unitarian Universalists (3), Muslims (3), Buddhists (2) and Hindus (2) in Congress are Democrats, as are the single members in the “other” and religiously unaffiliated categories.

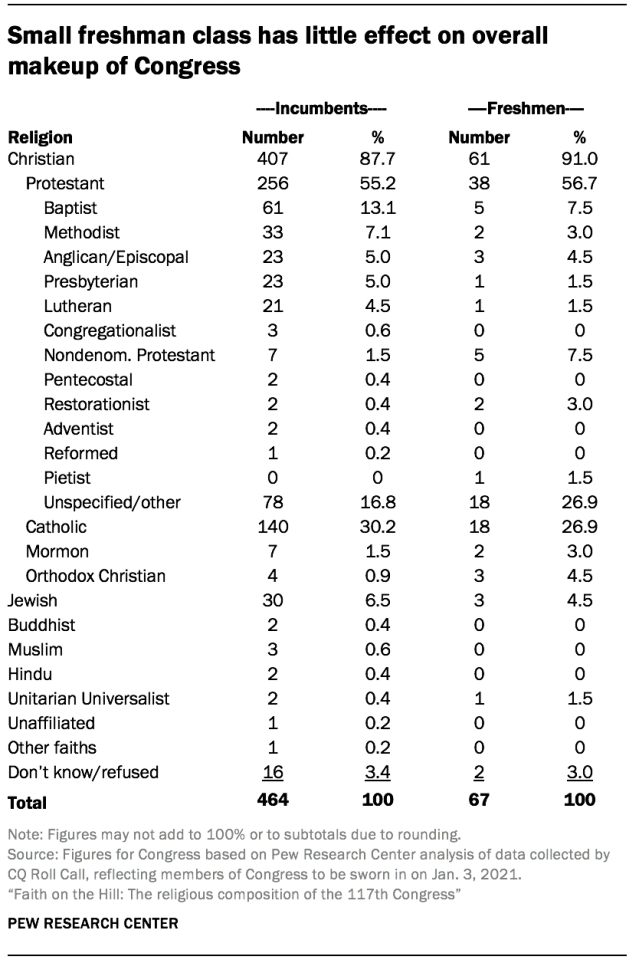

First-time members

While the small freshman class of the 117th Congress does little to change the overall makeup of the body, there are some notable differences in religious affiliation between incumbents and freshmen.

The freshman class is slightly more Christian than its incumbent counterpart. Just six of the 67 new members are not Christian: Three are Jewish, one is a Unitarian Universalist and two declined to share an affiliation.

The largest difference between newcomers and incumbents is in the share of Protestants who do not specify a denomination – 27% of freshmen are in this category, compared with 17% of incumbents. Similarly, those who specifically describe themselves as nondenominational Protestants make up 2% of incumbents and 7% of freshmen.

Among freshmen, there are two Restorationists – the same number as there are among incumbents.

Other Protestant subgroups are smaller among newcomers than they are among incumbents. For example, freshmen are less likely than incumbents to be Baptists (7% vs. 13%) or Methodists (3% vs. 7%).

Catholics, who make up 30% of Congress and 30% of incumbents, make up a smaller share of freshmen (27%). Orthodox Christians, on the other hand, make up just 1% of incumbents and 4% of freshmen (three new members).

Looking back

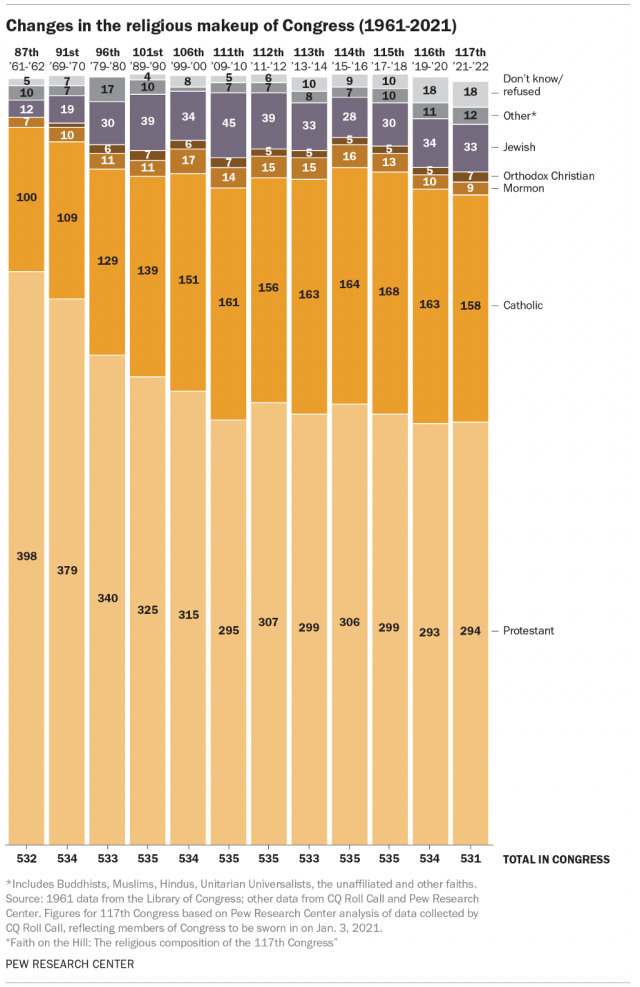

While the U.S. population continues to become less Christian, Congress has held relatively steady in recent years and has remained heavily Christian. In the 87th Congress (which began in 1961), the earliest for which aggregated religion data is available, 95% of members were Christian, which closely matched the roughly 93% of Americans who identified the same way at the time, according to historical religion data from Gallup.

Since the early ’60s, there has been a substantial decline in the share of U.S. adults who identify as Christian, but just a 7-point drop in the share of members of Congress who identify that way. Today, 88% of Congress is Christian, while 65% of U.S. adults are Christian, according to Pew Research Center surveys.