Giving a share of one’s income to the church has been a part of European tradition for centuries. Today, several countries continue to collect a “church tax” on behalf of officially recognized religious organizations, in some cases levying the tax on all registered members.1 These payments add up to billions of euros annually and represent the biggest source of revenue for many religious institutions.

But growing numbers of people have been opting out of the tax by formally deregistering from their churches, perhaps another sign of secularization in the region. Some European advocates for greater distance between church and state argue that church tax systems violate freedom of religion and have called for their abolition. This raises a number of questions: Are Europeans rushing away from financially supporting organized religion? Why do many people continue to pay church taxes even though they rarely partake in religious services? Are church taxes hastening secularization in the region?

To gain insight into these questions, Pew Research Center sought to measure public attitudes toward church taxes in several Western European countries where such taxes are collected. Researchers posed a few relevant questions to Germans, Swedes and others: Have you ever paid church taxes? Do you currently pay them? And if you do, how likely are you to consider opting out in the future? These questions were asked of nationally representative groups of respondents by telephone (both cellphones and landlines) in 2017 as part of a broader survey of religion in Western Europe.

Are Europeans rushing away from financially supporting organized religion?

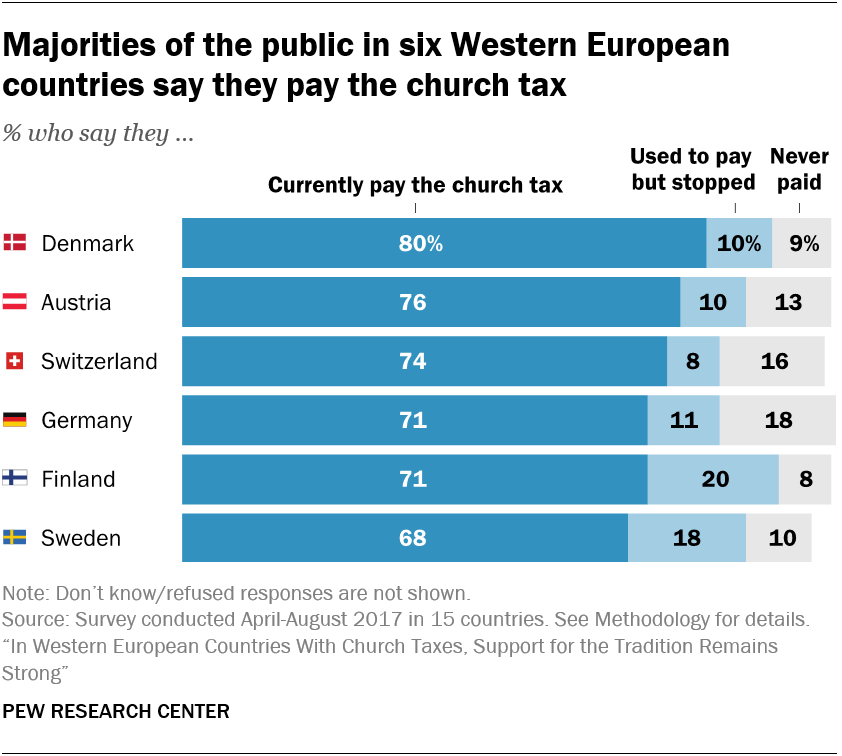

There is evidence that some Europeans are leaving the church tax system, but there does not appear to be a mass exodus. The survey finds that between 8% of adults (in Switzerland) and 20% (in Finland) say they have left their church tax system. And, in several countries, one-fifth or more of current payers describe themselves as either “somewhat” or “very” likely to opt out in the future.

There is evidence that some Europeans are leaving the church tax system, but there does not appear to be a mass exodus. The survey finds that between 8% of adults (in Switzerland) and 20% (in Finland) say they have left their church tax system. And, in several countries, one-fifth or more of current payers describe themselves as either “somewhat” or “very” likely to opt out in the future.

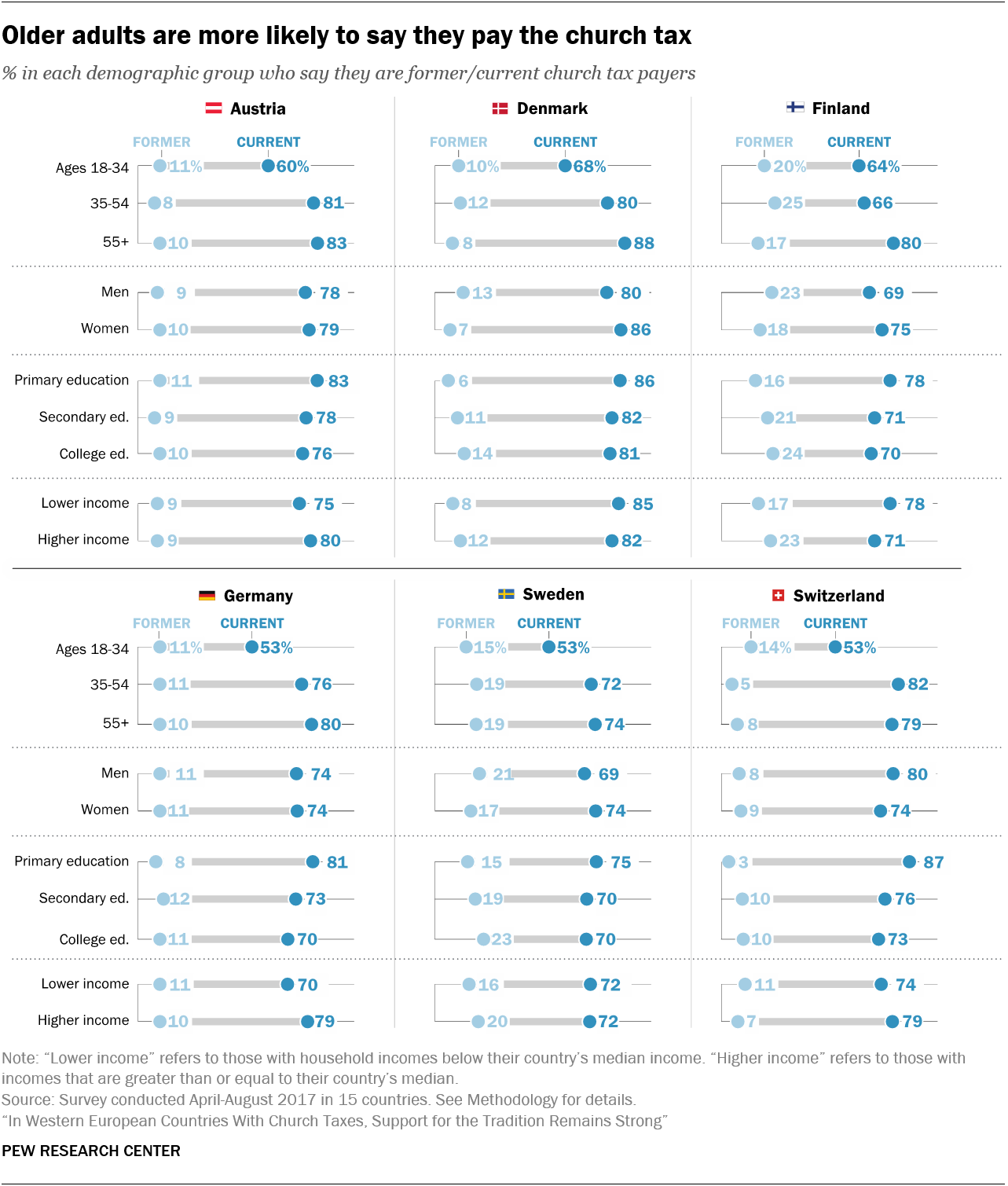

At the same time, majorities still support the tradition of paying taxes to religious institutions. Indeed, in six Western European countries with a mandatory tax on members of major Christian churches (and in some cases, other religious groups), most adults say they pay it. The share of self-reported church tax payers in these countries ranges from 68% of survey respondents in Sweden to 80% in Denmark, while no more than one-in-five in any country say they used to pay but have stopped.

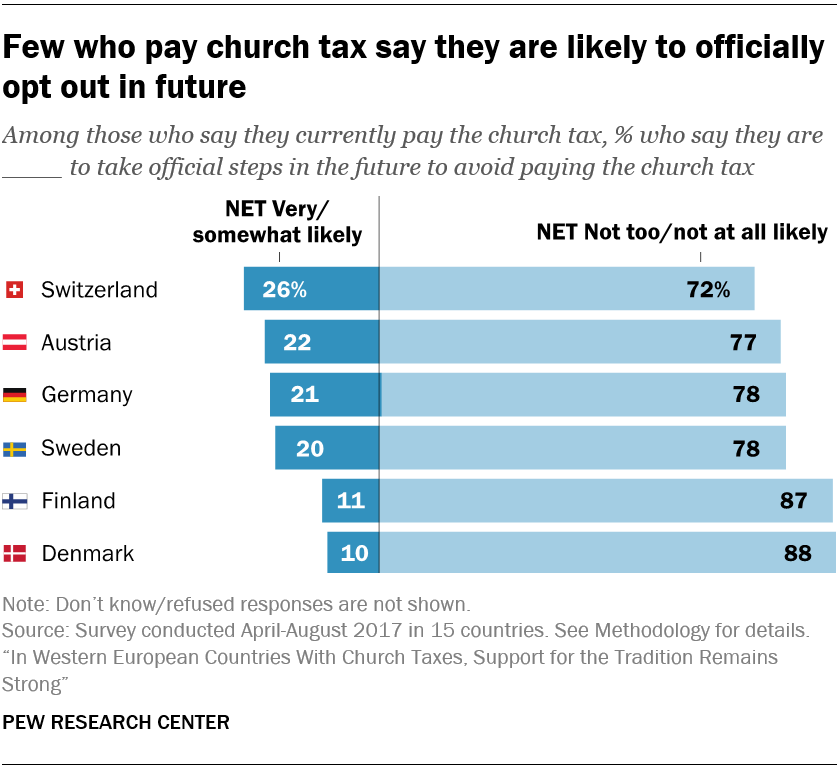

In addition, among those who say they pay, large majorities describe themselves as “not too” or “not at all” likely to take official steps to avoid paying the tax in the future, including nearly nine-in-ten in Denmark and Finland.

In addition, among those who say they pay, large majorities describe themselves as “not too” or “not at all” likely to take official steps to avoid paying the tax in the future, including nearly nine-in-ten in Denmark and Finland.

It should be noted that in Germany and Austria, the share of adults who say they pay the church tax starkly contrasts with official statistics. In Germany, where roughly seven-in-ten people surveyed say they pay the church tax, government data indicates the actual figure is only about a quarter of the adult population. And in Austria, 76% of survey respondents say they pay the tax, compared with the official estimate of about half (official estimates from Austria are for Catholics as reported by the Catholic Church; members of Protestant and Old Catholic denominations are also taxed, but these are a small portion of the population). In other countries, the gaps between self-reported numbers and official statistics are smaller.2

After ruling out other potential sources of large measurement error – such as the composition of the sample or question wording and translation – it seems likely that respondents answered this question on the basis of their eligibility or perceived obligation to pay the church tax. Furthermore, analysis of our survey data confirms that respondents who say they pay church taxes are attitudinally different from those who do not. At the very least, self-reported church tax payers think they are paying the tax or accept a general social obligation to pay such taxes, even if their personal circumstances might exempt them (for example, if they are retired, unemployed or earn low incomes). The perceived civic or religious obligation of paying church tax is a central point of debate in the countries surveyed – and a focus of this report.

Why do people say they pay the church tax even if they are not very religious?

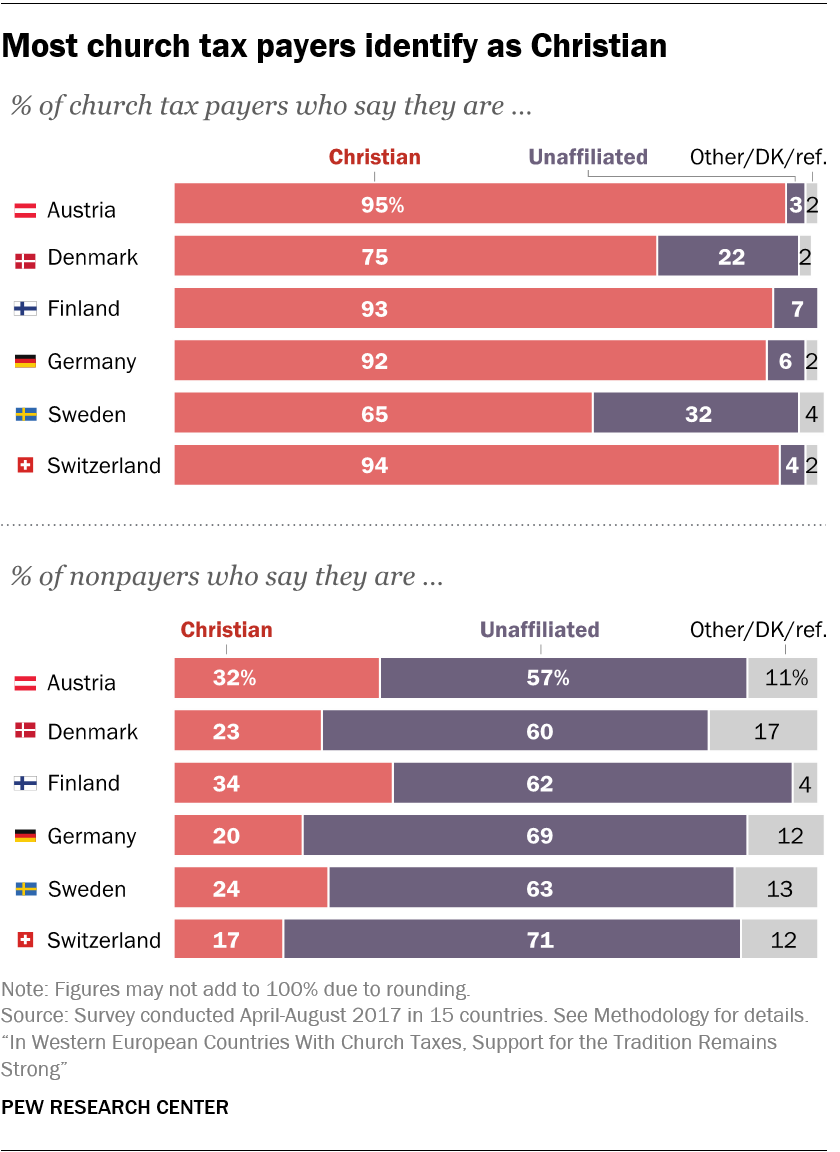

Religious identity is one obvious difference between people who say they pay the church tax and those who do not. Large majorities of self-reported church tax payers – including 95% in Austria and 94% in Switzerland – describe themselves as Christians, while most nonpayers say they are religiously unaffiliated (also known as religious “nones,” made up of those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”).3

Religious identity is one obvious difference between people who say they pay the church tax and those who do not. Large majorities of self-reported church tax payers – including 95% in Austria and 94% in Switzerland – describe themselves as Christians, while most nonpayers say they are religiously unaffiliated (also known as religious “nones,” made up of those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”).3

This dovetails with a possible explanation for the widespread support of church taxes. According to one theory, formally leaving a church and renouncing a part of one’s identity involves enough effort and symbolism that many people are deterred from taking that step, even if they are not religious. In countries with a mandatory church tax, people generally enter a church’s rolls at baptism – overwhelming majorities of Western European adults say they were baptized – and they must officially deregister from their denomination to avoid the fee. Not only is this a dramatic step for some, but it also requires knowledge that the option exists and how to exercise it, such as how to obtain and file the necessary forms. Staying on their church’s tax roster is the default status for people who are not sufficiently motivated to opt out.4

Still, not all church tax payers say they are Christians or members of other religious groups that benefit from the tax: Fully one-fifth (22%) of self-reported payers in Denmark and nearly a third (32%) in Sweden identify as religiously unaffiliated.

Religious “nones” make up a growing share of the population in Western Europe, and within this group, the percentage who say they pay the church tax ranges from 14% in Switzerland to a clear majority (60%) in Denmark. Not only that, but most Christians in the region say they attend church no more than a few times a year, yet large majorities say they pay the church tax. All of this raises a question: Why do people financially support religious institutions that they rarely – if ever – attend?

There are many reasons for this seeming contradiction, and explanations vary from person to person and country to country. However, one school of thought contends that many Europeans feel a culturally ingrained obligation to support the common good with taxes – and tend to see religious institutions as “public utilities” that help those in need.5

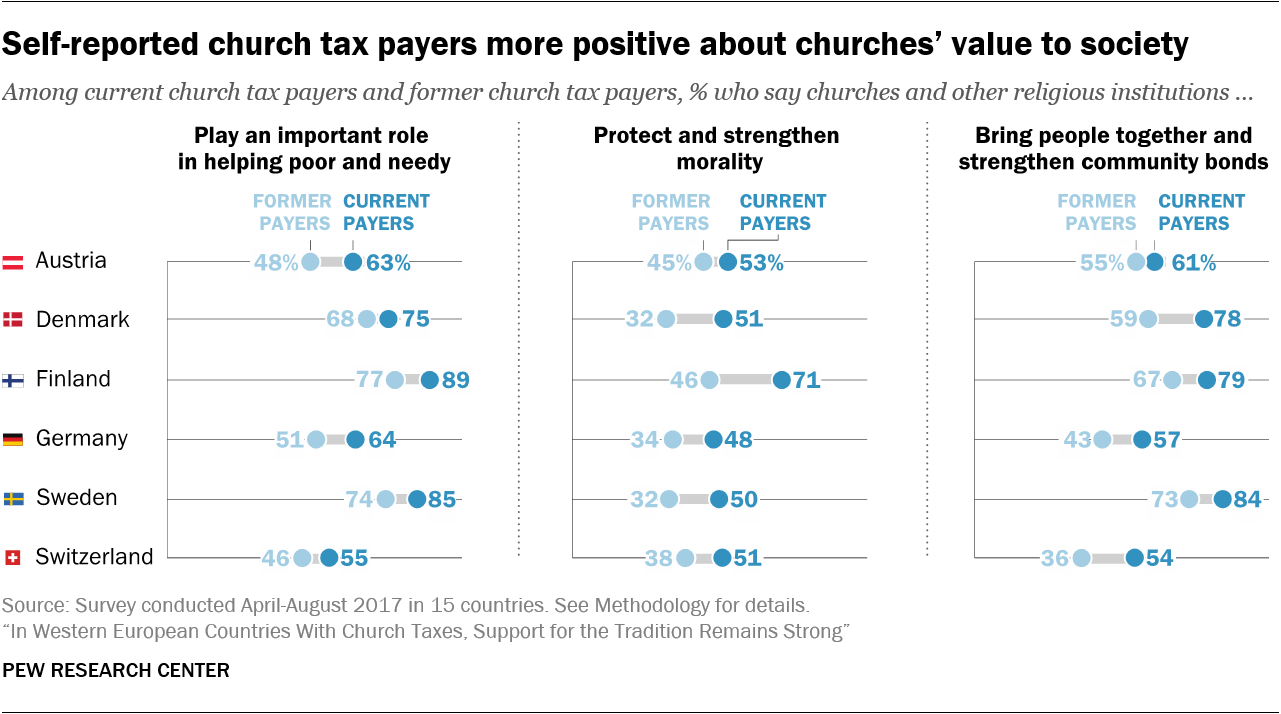

Indeed, the survey finds that across all six countries with church taxes, people who say they pay the tax tend to express more positive feelings about the impact of churches on society. For example, many self-reported payers say that churches and other religious institutions strengthen morality, bring people together and help the poor; on balance, fewer former church tax payers hold these views.6 Moreover, current taxpayers are less likely than former taxpayers to say that religion should be kept separate from government policies (see here).

Church tax payers also tend to be at least marginally more observant and place greater significance on religious belief. While most Western Europeans do not go to religious services regularly, those who say they pay church taxes are much more likely than former payers to say they at least sometimes attend services at a church or other house of worship, and they are also more likely to say that they believe in God and that religion is important in their lives. They may also want to have their own children baptized or to use a church on other special occasions – such as weddings or funerals – even though they are not regular attenders.7

Is the church tax pushing people away from Christian identity?

In several countries, members of the biggest Catholic and Protestant churches (and sometimes other religious groups) are subject to the tax, but people can avoid it by deregistering from their religious group. Theoretically, this may give people in these countries a financial incentive to disaffiliate. As a result, some social scientists have theorized that church taxes could be among the factors driving people away from religious organizations.8

In several countries, members of the biggest Catholic and Protestant churches (and sometimes other religious groups) are subject to the tax, but people can avoid it by deregistering from their religious group. Theoretically, this may give people in these countries a financial incentive to disaffiliate. As a result, some social scientists have theorized that church taxes could be among the factors driving people away from religious organizations.8

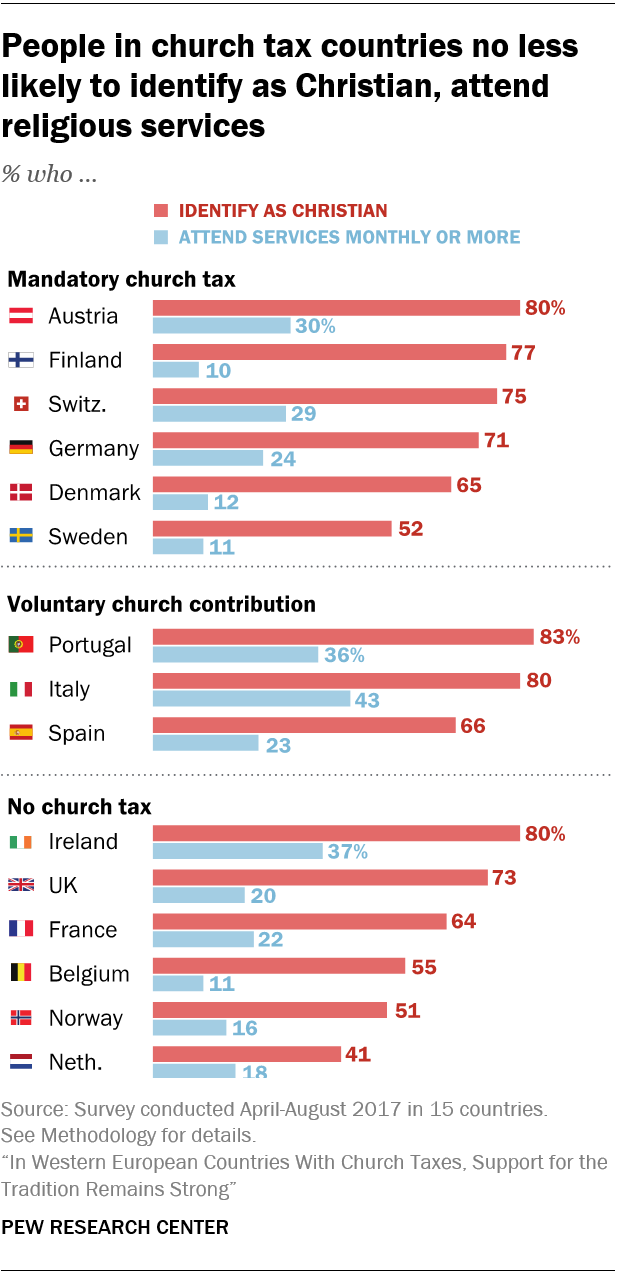

However, a comparison of responses across 15 Western European countries surveyed by Pew Research Center shows no obvious connection between secularization and the existence of a church tax.

Indeed, there is no evidence that church tax countries are experiencing more rapid declines in Christian identification than other countries in Europe. In all 15 Western European countries surveyed, fewer people say they are currently Christian than say they were raised Christian, and, in each case, more people say they are currently unaffiliated than say they were raised unaffiliated. But the countries with the steepest drops in Christian identification – including Belgium, Norway and the Netherlands – do not have church taxes.

If anything, people in countries with a mandatory church tax are more likely to self-identify as Christian than are people in Western European countries that do not have any church tax system. In four of the six countries surveyed that have mandatory church taxes for Christians (Austria, Finland, Germany and Switzerland), roughly seven-in-ten or more adults identify as Christians. In only two of the six countries surveyed that do not have a church tax (Ireland and the UK) does the share of Christians exceed seven-in-ten. Across Western Europe, the country with the smallest share of Christians (the Netherlands, 41%) does not have a church tax.

In addition, levels of religious observance are similar in Western European countries that have a mandatory church tax and those that do not have a church tax. For example, people in church tax countries are just as likely as people in surveyed Western European nations without church taxes to say they believe in God, pray daily, attend religious services monthly or consider religion important in their lives.

These are among the findings of Pew Research Center surveys conducted in Western Europe by telephone (both cellphones and landlines) in 2017. The Center surveyed 15 countries; this report focuses on six, but sometimes includes all 15 for comparison. This is the fourth report on the survey results. An initial analysis looked at Catholic-Protestant relations in Europe 500 years after the Protestant Reformation. Many further findings appeared in a study of Christian identity and secularization in Western Europe, and a follow-up report examined religion and nationalism across Europe, comparing countries in the East and West.

Countries included in the main analysis of this study are those that were surveyed and have a church tax. Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and most cantons of Switzerland have mandatory payment systems for registered church members; the systems have similar rules, allowing for straightforward comparisons. Spain and Portugal, which have voluntary church fee systems, are discussed separately here and in this sidebar. Italy, meanwhile, combines voluntary and mandatory elements in its “otto per mille” system, and is not included in this analysis. Iceland carves a church tax out of all income taxes it receives and passes it on to religious organizations based on their member count, but because Iceland was not part of the 2017 survey it is not part of this analysis.

In the remaining countries of Western Europe, such as France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, there are no church taxes, and religious groups receive funding entirely from other sources, including direct donations, state subsidies and financial investments.9 In many other places around the world, including the United States, tax exemptions for religious institutions also amount to a form of state support.

A prior Pew Research Center study looked at church-state relationships globally, including countries that have an official state religion or a preferred religion. This report focuses narrowly on church taxes in Western Europe.

Among the other findings:

- People who have opted out of the church tax in Western Europe are considerably more likely than those who say they pay to express support for the separation of church and state. But even among self-reported church tax payers, large majorities in some countries say religion should be kept separate from government policies.

- Although Europeans who say they pay church taxes tend to be more religious (by a variety of measures) than those who formerly paid the tax and have opted out, most people who say they currently pay the church tax are not regular churchgoers.

- Young adults (ages 18 to 34) are less likely to say they pay church taxes than older adults in the same countries. This is not because they are more likely than their elders to have opted out, but rather because higher shares of young Europeans say they have never paid church taxes in the first place, in part because some are students without taxable income. This aligns with the fact that young adults in Western Europe are less likely to identify with Christianity; many were raised without a religious affiliation and may have never been officially registered with a church.

- Income is not consistently correlated with proclivity for paying church tax. In Germany and Austria, people with higher incomes (greater than or equal to their country’s median income) are more likely than those with lower incomes to say they pay church taxes. But the reverse is true in Finland.

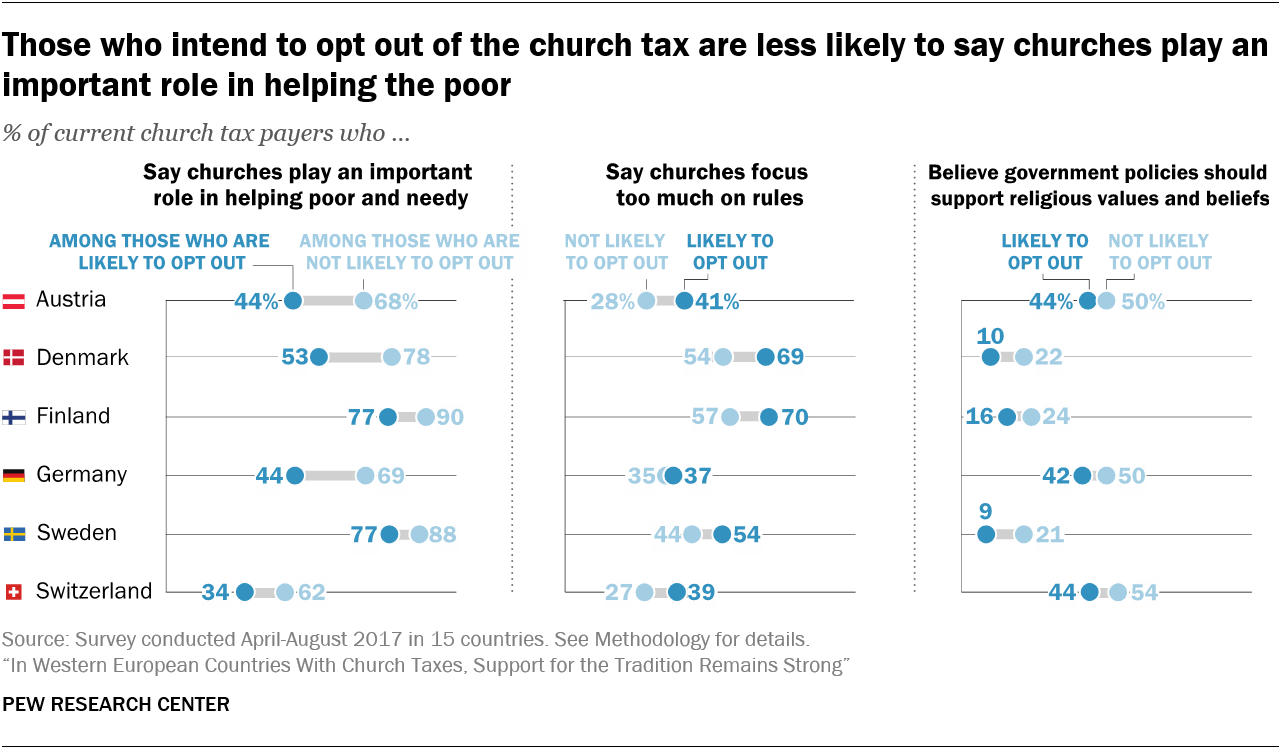

- People who say they are likely to opt out of paying the church tax are often – but not always – less religious than people in the same country who intend to keep paying it. The more consistent difference is how they regard religious institutions: Those who are considering opting out tend to hold more skeptical views about the impact of churches and other religious organizations on society.

Church tax systems across Europe

The rules that govern Western Europe’s church tax systems vary from country to country and sometimes even from parish to parish. Nevertheless, there are some commonalities. They typically involve a fee calculated either as a percentage of income or as a portion of total income tax owed. The money goes to churches and some other religious groups to help cover their costs, including clergy salaries, maintenance of buildings and charitable services.

In Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and most cantons of Switzerland, the church tax is mandatory for all adult members of major churches who meet minimum income criteria. That typically includes the majority of Christian taxpayers, but can exclude students, the unemployed, retirees and others with low earnings. Church membership usually is determined by baptism. Those who want to avoid the tax must deregister from their religious group; in most countries, a letter to the church is necessary, though websites recently have been set up (often by organizations advocating against the tax) to facilitate this process.10 In Germany, some states require a notarized deregistration form to be filed with local authorities who charge a fee to handle the paperwork.

In many cases, the tax is the largest source of funding for the country’s dominant church. For example, the Danish People’s Church received about 6.6 billion Danish kroner (roughly $1 billion) in church taxes in 2017, about three-quarters of its revenue that year. And in Austria, the Catholic Church (the country’s largest religious institution), collected 460 million euros in church taxes in 2017, making up a similar share of its revenue.

For individuals, meanwhile, the church tax typically amounts to less than 2% of taxable income. To give one concrete example: In Finland, the median income in 2017 was 23,602 euros, and the median amount paid in income taxes was 4,271 euros, including a median church tax of 262 euros (or slightly more than 1% of income) assessed on members of the country’s largest denomination, the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Differences in tax rates between countries can be hard to compare, because some countries calculate the tax as a percentage of taxable income (typically in the neighborhood of 1% or 2%) while other countries calculate it as a percentage of income tax owed (typically in the range of 8% to 21%).

In addition to the six countries mentioned above, Portugal and Spain also collect some taxes that are passed along to help support religious institutions. But in those two countries, the payments are voluntary, even for church members. Italy has yet another system, known as the otto per mille (eight per thousand). All Italian income tax payers contribute to a pool of funds, and they can choose whether their allocation goes to the Roman Catholic Church, some other religious institution or the government’s humanitarian efforts. Iceland, meanwhile, carves a set “parish fee” for each resident over the age of 16 out of the country’s income tax revenues. These funds are then passed on to religious organizations in proportion to how many members they have.

Sourcing details for this section are available in Appendix B.

A brief summary of church taxes in these 10 European countries follows.

Mandatory church tax systems (with opt-out provisions)

Austria’s Kirchenbeitrag

Rate: Roughly 1% of annual gross income after allowable deductions.

Who pays it: Members of the Austrian Catholic, Old Catholic and Protestant churches.

Rules: Taxpayers receive a quarterly or annual invoice from their church and make the payment directly to their church via bank transfer or online payment; opting out requires deregistering from the church. The payment is considered a fee, not a tax.

Total payers (2017): 3.4 million Catholics out of an estimated Austrian adult population of 7.2 million. Payer numbers for Old Catholic Church members and Protestants not available.

Amount collected (2017): The Catholic Church received 461 million euros from the Kirchenbeitrag, accounting for 76% of its revenue.

Denmark’s Kirkeskat

Rate: Fluctuates annually depending on economic conditions and parish budgets; the 2018 average was 0.87% of taxable income.

Who pays it: Members of the Church of Denmark.

Rules: Church tax is collected with income tax and redistributed to parishes; opting out requires leaving the church.

Total payers (2016): 3.41 million Danes out of an estimated adult population of 4.5 million.

Amount collected (2017): The Church of Denmark received 6.6 billion Danish kroner, accounting for roughly 75% of its funding.

Finland’s Kirkollisvero

Rate: Varies by location and parish budgets; in 2018 ranged from 1% to 2% of taxable income.

Who pays it: Members of the Evangelical Lutheran, Orthodox, German Evangelical Lutheran and Olaus Petri churches.

Rules: Church tax is collected with payroll tax and redistributed to parishes; opting out requires leaving the church.

Total payers (2016): 2.8 million taxpayers out of an estimated Finnish adult population of 4.4 million

Amount collected (2016): Finnish taxpayers paid 905 million euros to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in 2016, accounting for roughly 75% of its funding.

Germany’s Kirchensteuer

Rate: Most German states charge 9% of income tax; two states, including Bavaria, charge 8% of income tax.

Who pays it: Members of the Catholic and Protestant churches, in addition to members of some Jewish groups and Humanist groups. Other registered religious organizations – including those representing Mennonites, Jehovah’s Witnesses and a Muslim group – also are legally permitted to collect the tax, but do not do so.

Rules: Church tax is automatically collected along with income tax; the government manages the collection on behalf of religious organizations, which pay a fee to outsource this process. Opting out requires leaving the church.

Total payers (2014): 18.5 million people out of an estimated German adult population of 68.5 million.

Amount collected (2017): Germany’s Catholic and Protestant churches collected roughly 11.7 billion euros combined, accounting for almost half of their revenue.

Sweden’s Kyrkoavgift

Rate: Ranges between 0.8% and 1.5% of taxable income for Church of Sweden members depending on parish.

Who pays it: Members of the Church of Sweden; members of 15 other groups including the Roman Catholic Church and Muslim organizations may participate in a parallel fee system known as avgift till trossamfund (fee to religious communities).

Rules: Payments are collected with income tax; opting out requires leaving the church. The payment is considered a fee, not a tax.

Total payers (2017): 6.2 million people out of an estimated adult population of 7.8 million contributed to the Church of Sweden

Amount collected (2017): The Church of Sweden received 13.6 billion Swedish kronor ($1.7 billion), accounting for about 80% of its funding.

Switzerland’s Kirchensteuer

Rate: Varies by parish, canton and church. In the Swiss capital Bern, for example, it is 20.7% of income tax for Catholics and 18.4% of income tax for Protestants.

Who pays it: In most cantons, obligatory for members of the Catholic and Protestant churches who meet minimum income requirements.

Rules: Due to Switzerland’s highly decentralized federal structure, each of the country’s 26 cantons has a different tax system, some with relatively high church taxes and some with none at all. Many cantons also require businesses to pay the church tax.

Total payers: Not available.

Amount collected (2016): The Catholic and Protestant churches estimate that roughly 1.4 billion Swiss francs (about $1.4 billion) were collected from individuals. This is an estimate; official countrywide data is not available.

Other types of church tax systems

Iceland’s Sóknargjöld

Rate: A fixed amount is set annually depending on parish fee needs. In 2018, the monthly payment was 931 kronur (roughly $7.76) per person.

Who pays it: The government carves the payment out of its total income tax revenue on behalf of members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Iceland and dozens of other officially recognized religious or philosophy groups. These include Christian, Muslim and Buddhist groups, among others.

Rules: All Icelandic residents are automatically added to the Sóknargjöld roster at age 16 and assigned to their parents’ religious group unless they switch to another affiliation. The fee of Icelanders who declare themselves religiously unaffiliated is allocated to the national treasury.

Total members of the Church of Iceland with Sóknargjöld allocation (2018): 186,477 people out of an estimated adult population of 259,906.

Amount allocated to the Church of Iceland (2018): 2.1 billion Icelandic kronur (roughly $17.5 million).

Italy’s Otto Per Mille

Rate: 0.8% of the government’s total income tax revenue.

Who pays it: All Italian income taxpayers contribute to the otto per mille pool.

Rules: While the otto per mille (0.8%) is automatically carved out of the government’s income tax proceeds, taxpayers may choose how the funds are distributed. Choices include the Catholic Church, which receives the vast majority of otto per mille proceeds; about a dozen other religious organizations, including the Union of Italian Jewish Communities and the Italian Buddhist Union; and the state, which typically spends the proceeds on humanitarian efforts in Italy and overseas. The allocations of taxpayers who do not choose a destination are added into the wider otto per mille pool and divided according to the choices made by the taxpayers who did choose a destination.

Amount collected (2017): The Catholic Church received 986 million euros from the otto per mille mechanism, with about 80% of taxpayers (13.9 million) choosing this option.

Portugal

Rate: 0.5% of income tax.

Who pays it: Voluntary.

Rules: Taxpayers may assign 0.5% of their personal income tax liability to benefit an eligible church, charity or public interest entity.

Total payers: Not available.

Amount collected: Not available.

Spain’s Casilla de la Iglesia

Rate: 0.7% of income taxes owed.

Who pays it: Voluntary for anyone who files an income tax return.

Rules: Taxpayers may choose to contribute to the Catholic Church, to a fund for activities of general social interest, to both, or to neither. Organizations that receive money from the charity fund are chosen via a grant competition; they typically include international poverty alleviation groups as well as church-related charities such as Cáritas.

Amount collected (2017): 7.1 million taxpayers chose to give 0.7% of their income tax to the Catholic Church, amounting to nearly 260 million euros.

The church tax and views toward church-state relations

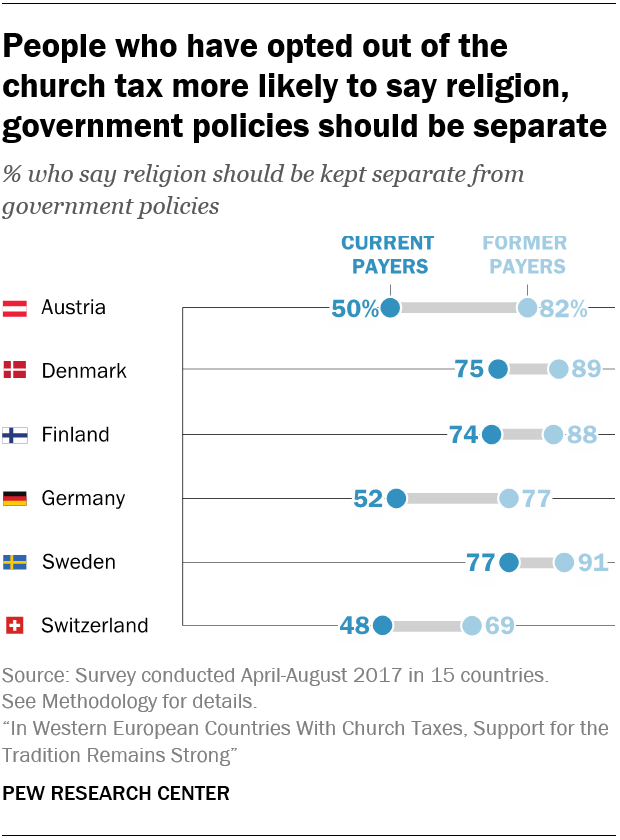

Within the six countries with mandatory church taxes for members, people who have opted out of the tax are more likely than those who say they currently pay to take the position that religion should be kept separate from government policies. And in each case, current payers are more likely to say that government policies should support religious values and beliefs. In some countries, the gaps are particularly stark: For example, the vast majority of Austrians who have opted out of the church tax (82%) say religion and government policies should be separate, while only half of those in Austria who say they pay the church tax take that position.

Within the six countries with mandatory church taxes for members, people who have opted out of the tax are more likely than those who say they currently pay to take the position that religion should be kept separate from government policies. And in each case, current payers are more likely to say that government policies should support religious values and beliefs. In some countries, the gaps are particularly stark: For example, the vast majority of Austrians who have opted out of the church tax (82%) say religion and government policies should be separate, while only half of those in Austria who say they pay the church tax take that position.

In Austria as well as Germany and Switzerland, self-reported church tax payers are about evenly split between those who say religion should be kept separate from government policies and those who say government policies should support religion. But in a few cases, even among payers, large majorities say religion should be kept separate from government policies. This includes about three-quarters of church tax payers in Sweden (77%), Denmark (75%) and Finland (74%), suggesting that for many residents of these countries, there is little tension between paying a church tax and, simultaneously, supporting the idea of church-state separation.

It may seem strange to Americans, accustomed to the principles of the U.S. Constitution, that people in Europe could favor separation of church and state while simultaneously paying church taxes. In fact, church-state separation is ingrained in the history of the church tax, which was introduced as an independent source of funding when many European governments began to scale back their financial support of clergy in the 19th century. And some Europeans argue that the church tax enhances the separation of church and state by creating a separate pool of funds for religious institutions to use as they see fit, without relying on government appropriations.11 (For more on the history of church taxes and church-state relations, see this sidebar.)

Origins of the church tax and the challenges it faces

Church taxes were introduced to help separate religion from government amid a wave of secularization that swept Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the system has survived many challenges – legal and otherwise – since that time.

Prior to Europe’s industrialization, the region’s religious and political leaders were closely connected. In some countries, senior clerics oversaw vast territories and held powerful political positions. Churches also held income-generating farmland, collected tithes from parishes and received other payments related to religious holidays and rites such as marriage. These revenue streams formed the basis of churches’ immense wealth.12

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, several economic and political shifts began to weaken the churches’ sovereignty. Some Enlightenment philosophers questioned traditional religious doctrine and spread new ideas about deism, while others argued for freedom of conscience. By the late 18th century, industrialization began to shift jobs away from farms to factories. Millions of Europeans moved out of tightly knit parishes to cities, where people were exposed to new ways of thinking about many things, including religion.

Meanwhile, following a series of military conflicts and territorial exchanges, churches in several European countries were forced to hand over much of their property to state entities, making them dependent on government funding.13

German states were among the first in Western Europe to introduce the church tax in the mid-1800s, after principalities were no longer able to uphold agreements to fund churches in exchange for land they had expropriated. Denmark and Sweden followed in the early 1900s, after agricultural reforms aimed at more equitable land ownership curbed churches’ tithing rights. In Austria, the church tax was introduced in 1939 by the Nazis. As part of a wider campaign to restrict church powers, the Nazi-led government confiscated the country’s existing “religion fund,” which had previously financed the clergy. Spain and Italy continued to support the Catholic Church out of government budgets until the late 1970s and mid-1980s, respectively, when both countries independently signed agreements with the Vatican curtailing the church’s privileges.

As Western European societies have become more religiously diverse in recent decades, governments have faced pressure to extend the tax option to a wider range of religious groups and even to nonreligious charities. In Sweden, for example, the government now allows more than a dozen religious organizations to participate in the system, though their fee is known as the “fee to religious communities” as opposed to the more widely known “church fee” that goes to the Church of Sweden.

In Germany, some humanist groups also collect the church tax, as do many Jewish organizations. Muslim groups in Germany do not take advantage of their right to levy a tax on their members, but some German politicians recently have called for the introduction of a new “mosque tax” to counter the influence of foreign funders in countries such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey who may seek to promote more radical interpretations of Islam.

Churches in countries that have a church tax depend heavily on it, but the arrangement is frequently challenged. For example, the Danish Atheist Society in 2016 ran an ad campaign, including ads on buses and online, calling for Danes to question their belief in God and urging them to visit a website that included simple instructions for deregistering from the national church. The campaign contributed to a surge in deregistrations in 2016, according to the Church of Denmark, which said that 24,728 people officially exited their faith in 2016, compared with only 9,979 the year prior.

And in Germany, the church tax has faced legal challenges – both from taxpayers who do not want their faith tied to a payment, and from expatriates who question churches’ jurisdiction over their religious identity.14 In 2012, Germany’s top administrative court ruled against Hartmut Zapp, a retired professor of church law, who had argued that he could continue to be a Catholic and participate in his congregation, even though he had officially deregistered from the legal statutory body that constituted the Catholic Church in Germany. The court, however, equated deregistration with an exit from the church itself, effectively siding with the German bishops conference, which says that Catholics who have deregistered from the church no longer qualify to receive services such as confession and Holy Communion.

Expatriates in Germany are often caught off guard by the tax, sometimes discovering that they owe it after they have received their tax bill. In 2015, Italian soccer player Luca Toni won a court case against the German accountants who managed his taxes while he played for Bayern Munich, arguing they had not adequately informed him about his obligation to pay the church tax and blaming them for a huge bill that had piled up as a result. A German court ruled in his favor and awarded him 1.25 million of the 1.7 million euros he owed. “If I’d have known how much it costs to be Catholic here (in Germany), I would have immediately left the church,” Toni reportedly said.

In Switzerland, which often settles national debates with referendums, voters in 1980 overwhelmingly rejected a constitutional amendment that would have eliminated churches’ authority to collect taxes and formally separated church and state. Today, one of the biggest controversies about the Swiss church tax revolves around some cantons (the Swiss equivalent of states or provinces) requiring corporations, foundations and other legal entities to pay it. Critics argue that the practice is unfair because these organizations cannot opt out.

And in Spain, the left-leaning prime minister Pedro Sánchez, who took office in 2018, has said he wants to cancel an agreement signed with the Vatican that guarantees funding to the church through the tax, in addition to scaling back other church privileges, such as tax exemption and state subsidies.

Although these debates raise questions about the long-term future of the church tax in Western Europe, millions of people pay it and, as this report shows, many say they plan to continue doing so.

People who say they pay the church tax tend to be more religious than former payers

While countries that do not have a church tax resemble those that have a church tax on many indicators of religious observance, there is a difference within church tax countries between people who report paying the tax and people who have opted out.

While countries that do not have a church tax resemble those that have a church tax on many indicators of religious observance, there is a difference within church tax countries between people who report paying the tax and people who have opted out.

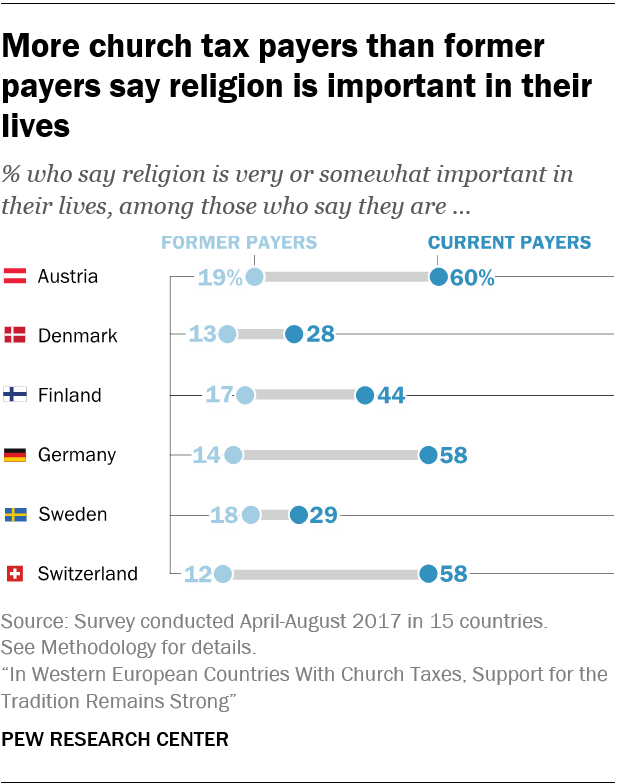

As one might expect, people who say they pay the church tax are more religious than former payers on a variety of measures. They are more likely to say they attend church and pray regularly, believe in God, and view religion as important in their lives. In Austria, for example, 60% of church tax payers say religion is at least somewhat important in their lives, compared with just 19% of former payers who say this. And in Germany, 77% of payers say they believe in God, compared with just 19% among those who have opted out of the tax.

At the same time, however, it is notable in some countries how relatively few self-reported church tax payers are highly religious in conventional ways. For example, among those who say they pay the tax, only about three-in-ten in Denmark and Sweden (28% and 29%, respectively) say religion is at least somewhat important to them – meaning that about seven-in-ten report paying the church tax even though they consider religion to be either “not too” or “not at all” important in their lives.

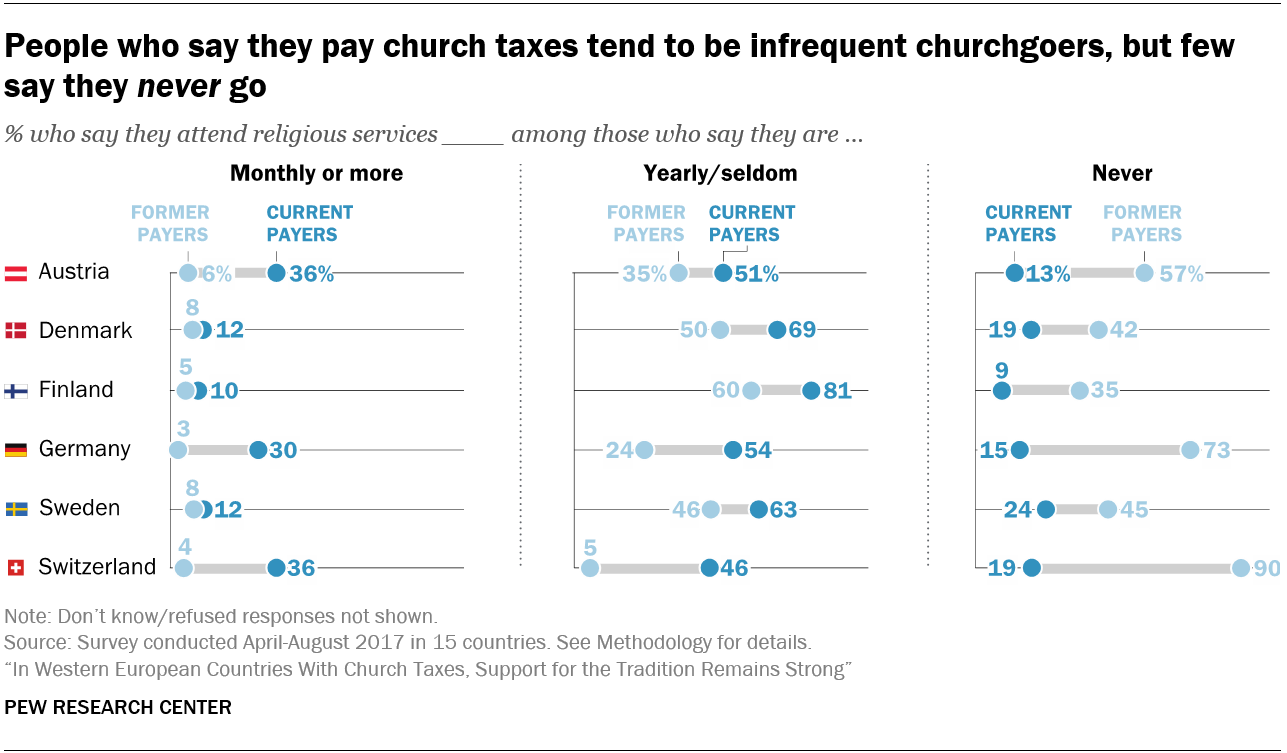

Similarly, current church tax payers are more likely than former payers to say they attend church at least monthly. But, in several countries, most people who say they pay church taxes do not attend church regularly. For example, in Switzerland, the majority of church tax payers – 64% – say they go to church less than once a month. Just 36% of Swiss church tax payers report attending church monthly or more. Former payers tend to go even less often; in Switzerland, just 4% of former payers say they go to church on a monthly basis.

Another important difference between current church tax payers and former payers is the percentage who say they never attend church. Compared with the shares who say they go to church at least sometimes, relatively few self-reported church tax payers in the countries surveyed say they never go to religious services. This suggests that for many people who pay church taxes, going to church is still something they do occasionally – even if just once or twice a year, perhaps at Christmas or Easter. Many people who have opted out of the tax, on the other hand, say they never go to church, including the vast majority of such people in Switzerland (90%) and Germany (73%).

Church tax payment does not vary consistently by income, but young adults are less likely to pay

Generally, across Western Europe, gender and education are not consistently correlated with people’s likelihood of paying a church tax. Even income levels do not have a clear relationship with people’s decisions about whether to pay the church tax. In Finland, for example, people with lower incomes (that is, those with income lower than the median) are more likely to pay the church tax, while in Germany and Austria those with higher incomes (those with incomes at the national median or higher) are more likely to pay. And while church tax payment varies by region in each country, most people across regions say they pay the tax.

But there is at least one overarching demographic pattern across the continent: Older people (ages 35 and older) are more likely than younger adults (ages 18 to 34) to say they pay church tax. This is mainly because young adults are more likely than older adults to say they have never paid the tax, reflecting lower rates of Christian affiliation among young Europeans. And it’s worth noting that in most of the countries surveyed, young adults are about as likely as older people in the same countries to be former church tax payers, even though presumably they have had fewer years in the tax system and, hence, less time to drop out.

There may also be a life cycle effect at work. Young people generally are less likely to ever have paid income taxes at all, perhaps because many are still students or have very low incomes at the beginning of their careers. As they get older, some may start to pay church taxes along with income taxes. However, the evidence suggests that a surge of young adults starting to pay church taxes is unlikely: In countries where the adequate sample sizes of young nonpayers are available, most are religiously unaffiliated. Far fewer (for example, 29% in Austria, 20% in Switzerland and 16% in Germany) identify as Christians.

As a single snapshot in time, the survey cannot conclusively determine whether the percentage of Europeans who pay church taxes has decreased, increased or stayed about the same in recent years. However, churches in countries including Finland, Germany and Sweden have asserted that the number of church tax payers has declined; it will probably continue to do so. The survey data suggests that the change may result not only from people opting out of the tax but also from generational replacement: Young people in Western Europe are less likely to have been baptized, and many are entering adulthood without a religious affiliation and without paying church taxes, replacing older generations of more heavily Christian church tax payers.

Indeed, being Christian is another – perhaps obvious – characteristic that is strongly correlated with paying the church tax.

The survey finds that self-identified Christians are much more likely to say they pay the tax, while religiously unaffiliated people are considerably more likely to say they have opted out of paying. And in a statistical model built on the survey data that controls for religious affiliation and other personal characteristics, Christian identity, much more than any other demographic indicator, goes hand in hand with whether a person pays the church tax or not. While age does have a modest independent correlation with paying the church tax – that is, young people are less likely to pay, even when controlling for religious affiliation – the statistical link between paying the tax and being Christian is several times more powerful.15

In some countries, young church tax payers and those with a college education are more likely to say they intend to opt out

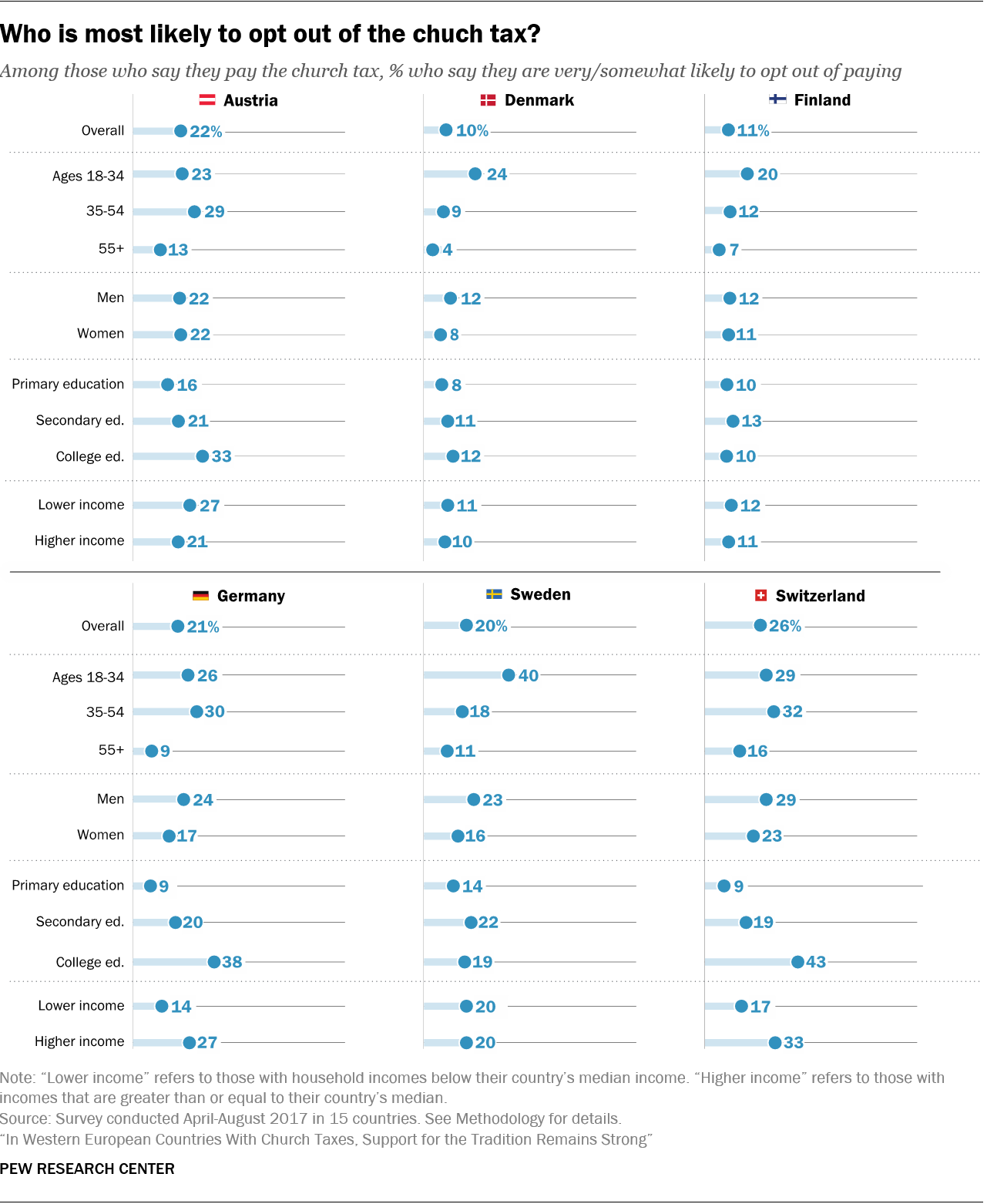

Not all people who say they pay the church tax intend to continue doing so in the future. While most self-reported church tax payers say they are unlikely to take official steps to opt out of the tax, substantial minorities say they are “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to do so (see this chart).

Who are the church tax payers most likely to opt out of paying in the future? Just as there are few demographic differences between current church tax payers and those who have already opted out, the patterns that distinguish ambivalent church tax payers from those who have no plans to stop paying vary by country.

In the three Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland and Sweden), for example, young church tax payers (ages 18 to 34) are more likely than others to say they plan to opt out. This pattern is particularly stark in Sweden; four-in-ten young Swedish church tax payers (40%) say they are at least somewhat likely to opt out, compared with 18% of those ages 35 to 54 and 11% of those 55 and older.

Meanwhile, in Austria, Germany and Switzerland, church tax payers under 35 are no more likely than those ages 35 to 54 to say they plan to opt out, although both of these age groups are more likely than the oldest cohort (ages 55 and older) to consider formally deregistering from their church or other religious organization.

Education makes a clear difference in Austria, Germany and Switzerland, in that payers with a college education are substantially more likely to say they intend to opt out. In Switzerland, for instance, 43% of college-educated adults say they are very or somewhat likely to stop paying the church tax, compared with 19% of those with a secondary education and only 9% of those with a primary education. This pattern is not seen in the Nordic countries.

In some countries, men are somewhat more likely than women to say they plan to opt out of the tax, but, overall, most men and women say they plan to keep paying in the future. Differences by income are similarly modest; the only exceptions are in Germany and Switzerland, where payers with higher incomes are more likely than others to say they plan on opting out.

People who intend to opt out of paying church taxes are less likely to view churches as playing a positive role in society

As previously noted, current church tax payers generally hold more positive views of the impact of churches on society than former payers do. (See this chart.) Similarly, the survey finds that Europeans who say they are likely to opt out of paying the church tax are considerably less likely to express positive views of churches’ contributions to society than are those who say they plan to keep paying the tax.

For example, in Denmark, people who intend to continue paying the tax overwhelmingly say churches “play an important role in helping the poor and needy” (78%), a view that is less common among current payers who are considering steps to opt out (53%). The same is true in Switzerland, where church tax payers who intend to opt out are about half as likely as those who intend to keep paying the tax to say churches and other religious institutions play an important role in helping the poor and needy (34% vs. 62%).

There is also a gap between these two groups on negatively worded questions about churches and religious institutions. In Austria, for instance, people who say they may stop paying the church tax are more likely than those who intend to keep paying it to say churches “focus too much on rules” (41% vs. 28%).

Further, in most countries, people who are considering opting out of church taxes are less likely to support government involvement in religion. In Germany, for example, 42% of those who intend to opt out of the tax say the state should support religious values, compared with 50% of taxpayers who do not plan to opt out.

When it comes to religious observance, however, those who intend to opt out are not necessarily less likely to go to church or to say religion is important in their lives. In Germany, similar shares of both groups say they attend church on a monthly basis (31% vs. 30%). The same is true for the shares who say religion is important in their lives (56% vs. 60%) or that they believe in God (74% vs. 79%).

Still, those who intend to opt out of paying church taxes are less likely to see themselves as a “religious person.” A majority of Germans (56%) who say they will continue to pay the tax say they would describe themselves as religious, compared with 38% among those who say they may stop paying in the future.

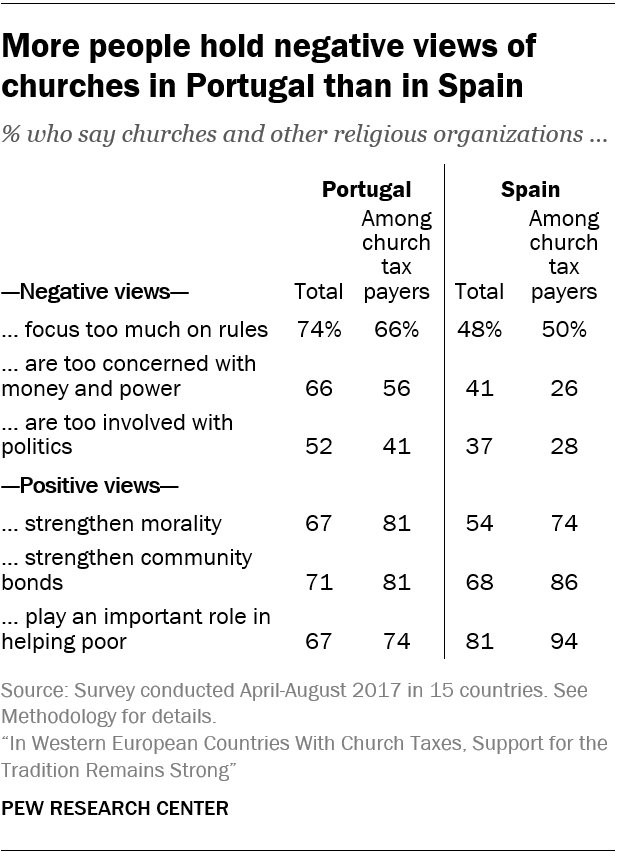

More people in Spain than Portugal pay voluntary church tax

Unlike countries where paying the church tax is mandatory for members of religious groups, Spain and Portugal give people the option of donating a share of their income tax to support churches or other charitable organizations. Although the systems are similar, the share who say they pay the tax is considerably higher in Spain (27%) than in Portugal (14%).

This is true even though by standard measures of religious observance, Portugal is a more religious country. For example, more than a third (36%) of people in Portugal say they attend church monthly, compared with 23% in Spain.

This is true even though by standard measures of religious observance, Portugal is a more religious country. For example, more than a third (36%) of people in Portugal say they attend church monthly, compared with 23% in Spain.

One possible explanation for this pattern could be that despite their higher levels of religious observance, people in Portugal are more critical of churches and other religious institutions than are Spaniards. While they see some positive contributions of these institutions to society, majorities of adults in Portugal say churches and other religious institutions “focus too much on rules” (74%) and that they “are too concerned with money and power” (66%). And about half (52%) of Portuguese adults say churches and other religious institutions “are too involved in politics.”

One possible explanation for this pattern could be that despite their higher levels of religious observance, people in Portugal are more critical of churches and other religious institutions than are Spaniards. While they see some positive contributions of these institutions to society, majorities of adults in Portugal say churches and other religious institutions “focus too much on rules” (74%) and that they “are too concerned with money and power” (66%). And about half (52%) of Portuguese adults say churches and other religious institutions “are too involved in politics.”

In Spain, fewer people agree with these negative statements about religious institutions, while Spaniards are considerably more likely to say religious institutions play an important role in helping the poor and needy (81% vs. 67% in Portugal).

Even among adults in both countries who do pay church taxes, the Portuguese are more likely to express criticism toward religious institutions. For example, a slim majority (56%) of church tax payers in Portugal say churches and other religious institutions are too concerned with money and power, compared with 26% among Spanish church tax payers. And Spaniards who pay the church tax overwhelmingly say religious institutions play an important role in helping the poor and needy (94%), compared with a smaller majority of those in Portugal (74%).