Darwin in America

The evolution debate in the United States

Almost 160 years after Charles Darwin publicized his groundbreaking theory on the development of life, Americans are still arguing about evolution. In spite of the fact that evolutionary theory is accepted by all but a small number of scientists, it continues to be rejected by many Americans. In fact, about one-in-five U.S. adults reject the basic idea that life on Earth has evolved at all. And roughly half of the U.S. adult population accepts evolutionary theory, but only as an instrument of God’s will.

Most biologists and other scientists contend that evolutionary theory convincingly explains the origins and development of life on Earth. Moreover, they say, a scientific theory is not a hunch or a guess, but is instead an established explanation for a natural phenomenon, like gravity, that has repeatedly been tested and refined through observation and experimentation.

So if evolution is as established in the scientific community as the theory of gravity, why are people still arguing about it more than century and a half after Darwin proposed it? The answer lies, in large part, in the theological implications of evolutionary thinking. For many religious people, the Darwinian view of life – a panorama of brutal struggle and constant change – conflicts with both the biblical creation story and the Judeo-Christian concept of an active, loving God who intervenes in human events. (See “Religious Groups’ Views on Evolution.”)

This basic concern with evolutionary theory has helped drive the decadeslong opposition to teaching it in public schools. Even over the last 15 years, educators, scientists, parents, religious leaders and others in more than a dozen states have engaged in public battles in school boards, legislatures and courts over how school curricula should handle evolution. The issue was even discussed and debated during the runups to the 2000 and 2008 presidential elections. This battle has ebbed in recent years, but it has not completely died out.

Outside the classroom, much of the opposition to evolution has involved its broader social implications and the belief that it can be understood in ways that are socially and politically dangerous. For instance, some social conservatives charge that evolutionary theory serves to strengthen broader arguments that justify practices they vehemently oppose, such as abortion and euthanasia. Evolutionary theory also plays a role in arguments in favor of transhumanism and other efforts to enhance human abilities and extend the human lifespan. Still other evolution opponents say that well-known advocates for atheism, such as Richard Dawkins, view evolutionary theory not just as proof of the folly of religious faith, but also as a justification for various types of discrimination against religion and religious people.

A look back at American history shows that, in many ways, questions about evolution have long served as proxies in larger debates about religious, ethical and social norms. From efforts on the part of some churches in the 19th and early 20th centuries to advance a more liberal form of Christianity, to the more recent push and pull over the roles of religion and science in the public square, attitudes toward evolution have often been used as a fulcrum by one side or the other to try to advance their cause.

Darwin comes to America

In formulating his theory of evolution through natural selection, Charles Darwin did not set out to create a public controversy. In fact, his concerns over how his ideas would be received by the broader public led him to wait more than 20 years to publicize them. He might never have done so if another British naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, had not in 1858 independently come up with a very similar theory. At that point, Darwin, who had already shared his conclusions with a small number of fellow scientists, finally revealed his long-held ideas about evolution and natural selection to a wider audience.

Darwin built his theory on four basic premises. First, he argued, each animal is not an exact replica of its parents, but is different in subtle ways. Second, he said, although these differences in each generation are random, some of them convey distinct advantages to an animal, giving it a much greater chance to survive and breed. Over time, this beneficial variation spreads to the rest of the species, because those with the advantage are more likely than those without it to stay alive and reproduce. And, finally, over longer periods of time, cumulative changes produce new species, all of which share a common ancestor. (For more on this, see “Darwin and His Theory of Evolution.”)

In November 1859, Darwin published “On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection,” which laid out his theory in detail. The book became an instant bestseller and, as Darwin had feared, set off a firestorm of controversy in his native Britain. While many scientists defended Darwin, religious leaders and others immediately rejected his theory, not only because it directly contradicted the creation story in the biblical book of Genesis, but also because – on a broader level – it implied that life had developed due to natural processes rather than as the creation of a loving God.

In the United States, which was on the verge of the Civil War, the publication of “Origin” went largely unnoticed. By the 1870s, American religious leaders and thinkers had begun to consider the theological implications of Darwin’s theory. Still, the issue didn’t filter down to the wider American public until the end of the 19th century, when many popular Christian authors and speakers, including the famed Chicago evangelist and missionary Dwight L. Moody, began to inveigh against Darwinism as a threat to biblical truth and public morality.

At the same time, other dramatic shifts were taking place in the country’s religious landscape. From the 1890s to the 1930s, the major American Protestant denominations gradually split into two camps: modernist, or theologically liberal Protestantism (what would become mainline Protestantism); and evangelical, or otherwise theologically conservative, Protestantism.

This schism owed to numerous cultural and intellectual developments of the era, including, but not limited to, the advent of new scientific thinking. Theologians and others also grappled with new questions about the historical accuracy of biblical accounts, as well as a host of provocative and controversial new ideas from such thinkers as Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud about both the individual and society. Modernist Protestants sought to integrate these new theories and ideas, including evolution, into their religious doctrine, while more conservative Protestants resisted them.

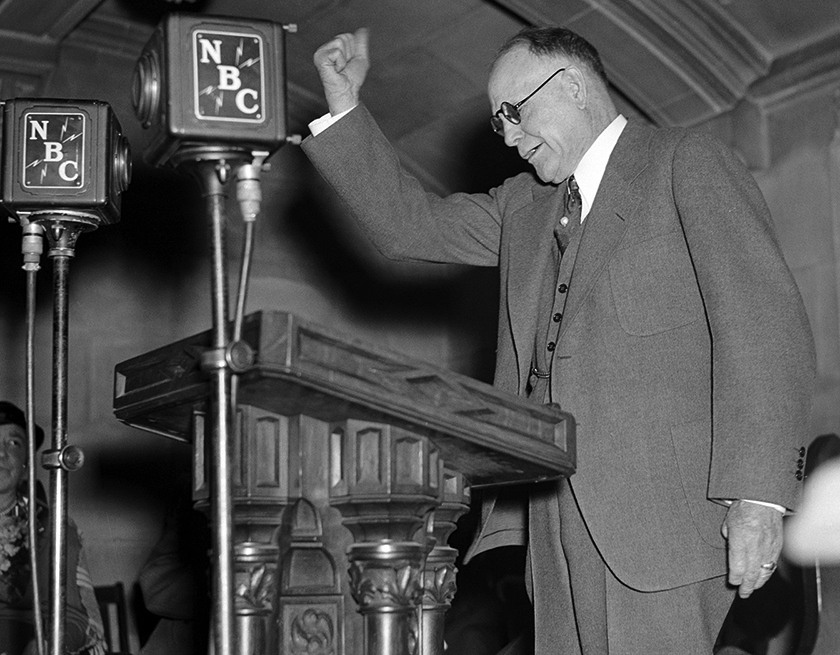

By the early 1920s, evolution had become perhaps the most important wedge issue in this Protestant divide, in part because the debate had taken on a pedagogical dimension, with students throughout the nation now studying Darwin’s ideas in biology classes. The issue became a mainstay for Protestant evangelists, including Billy Sunday, the most popular preacher of this era. “I don’t believe the old bastard theory of evolution,” he famously exclaimed during a 1925 revival meeting. But it was William Jennings Bryan, a man of politics, not the cloth, who ultimately became the leader of a full-fledged national crusade against evolution.

Bryan, a populist orator and devout evangelical Protestant who had thrice run unsuccessfully for president, believed that teaching of evolution in the nation’s schools would ensure that whole generations would grow up believing that the Bible was no more than “a collection of myths,” and would undermine the country’s Christian faith in favor of the doctrine of “survival of the fittest.”

Bryan’s fear of social Darwinism was not entirely unfounded. Evolutionary thinking had helped birth the eugenics movement, which maintained that one could breed improved human beings in the same way that farmers breed better sheep and cattle. Eugenics led to now-discredited theories of race and class superiority that helped inspire Nazi ideology; in America, some used social Darwinism to argue in favor of restricting immigration (particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe) or to enact state laws requiring sterilization to stop “mental deficients” from having children.

Many who favored the teaching of evolution in public schools did not support eugenics, but simply wanted students to be exposed to the most current scientific thinking. For others, like supporters of the newly formed American Civil Liberties Union, teaching evolution was an issue of freedom of speech as well as a matter of maintaining a separation of church and state. And still others, like famed lawyer Clarence Darrow, saw the battle over evolution as a proxy for a wider cultural conflict between what they saw as progress and modernity on the one side, and religious superstition and backwardness on the other.

Scopes and its aftermath

At the urging of Bryan and evangelical Christian leaders, evolution opponents tried to ban the teaching of Darwin’s theory in a number of states. Although early legislative efforts failed, evolution opponents won a victory in 1925 when the Tennessee Legislature overwhelmingly approved legislation making it a crime to teach “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible.” Soon after the Tennessee law was enacted, the ACLU offered to defend any science teacher in the state who was willing to break it. John Scopes, a teacher in the small, rural town of Dayton, Tennessee, agreed to take up the ACLU’s offer.

The subsequent trial popularly referred to as the Scopes “monkey” trial, was one of the first true media trials of the modern era, covered in hundreds of newspapers and broadcast live on the radio. Defending Scopes was Darrow, then the most famous lawyer in the country. And joining state prosecutors was Bryan. From the start, both sides seemed to agree that the case was being tried more in the court of public opinion than in a court of law.

As the trial progressed, it seemed increasingly clear that Darrow’s hope of spurring public debate over the merits of teaching evolution was being stymied by state prosecutors. But then Darrow made the highly unorthodox request of calling Bryan to the witness stand. Although the politician was under no obligation to testify, he acceded to Darrow’s invitation.

With Bryan on the stand, Darrow proceeded to ask a series of detailed questions about biblical events that could be seen as inconsistent, unreal or both. For instance, Darrow asked, how could there be morning and evening during the first three days of biblical creation if the sun was not formed until the fourth? Bryan responded to this and similar questions in different ways. Often, he defended the biblical account in question as the literal truth. On other occasions, however, he admitted that parts of the Bible might need to be interpreted in order to be fully understood.

Scopes was convicted of violating the anti-evolution law and fined, although his conviction was later overturned by the Tennessee Supreme Court on a technicality. But the verdict was largely irrelevant to the broader debate. The trial, particularly Darrow’s questioning of Bryan, created a tremendous amount of positive publicity for the pro-evolution camp, especially in northern urban areas, where the media and cultural elites were sympathetic toward Scopes and his defense.

At the same time, this post-Scopes momentum did not destroy the anti-evolution movement. Indeed, in the years immediately following Scopes, the Mississippi and Arkansas state legislatures enacted bills similar to Tennessee’s. Other states, particularly in the South and Midwest, passed resolutions condemning the inclusion of material on evolution in biology textbooks. These actions, along with a patchwork of restrictions from local school boards, prompted most publishers to remove references to Darwin from their science textbooks.

Efforts to make evolution the standard in all biology classes stalled, due largely to the fact that the government prohibition on religious establishment or favoritism, found in the establishment clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, applied at the time only to federal and not state actions. State governments could set their own policies on church-state issues. Only in 1947, with the Supreme Court’s decision in Everson v. Board of Education, did the constitutional prohibition on religious establishment begin to apply to state as well as federal actions. Evolution proponents also received a boost a decade after Everson, in 1957, when the Soviet launch of the first satellite, Sputnik I, prompted the United States to make science education a national priority.

Meanwhile, beginning in the late 1960s, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a number of important decisions that imposed severe restrictions on state governments that opposed the teaching of evolution. In 1968, in Epperson v. Arkansas, the high court unanimously struck down as unconstitutional an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools. Specifically, the justices said, the law violated the First Amendment’s establishment clause because it sought to prevent students from learning a particular viewpoint antithetical to conservative Christianity, and thus promoted religion.

Almost 20 years after Epperson, the court issued another key ruling, this time involving the teaching of “creation science” in public schools. Proponents of creation science contend that the weight of scientific evidence supports the creation story as described in the biblical book of Genesis, with the formation of Earth and the development of life occurring in six 24-hour days. The presence of fossils and evidence of significant geological change are attributed to the catastrophic flood described in the eighth chapter of Genesis.

In Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), the high court struck down a Louisiana law requiring public schools to teach “creation science” alongside evolution, ruling (as in Epperson) that the statute violated the establishment clause because its aim was to promote religion. (For more on the legal aspects of the evolution debate, see “The Social and Legal Dimensions of the Evolution Debate in the U.S.”)

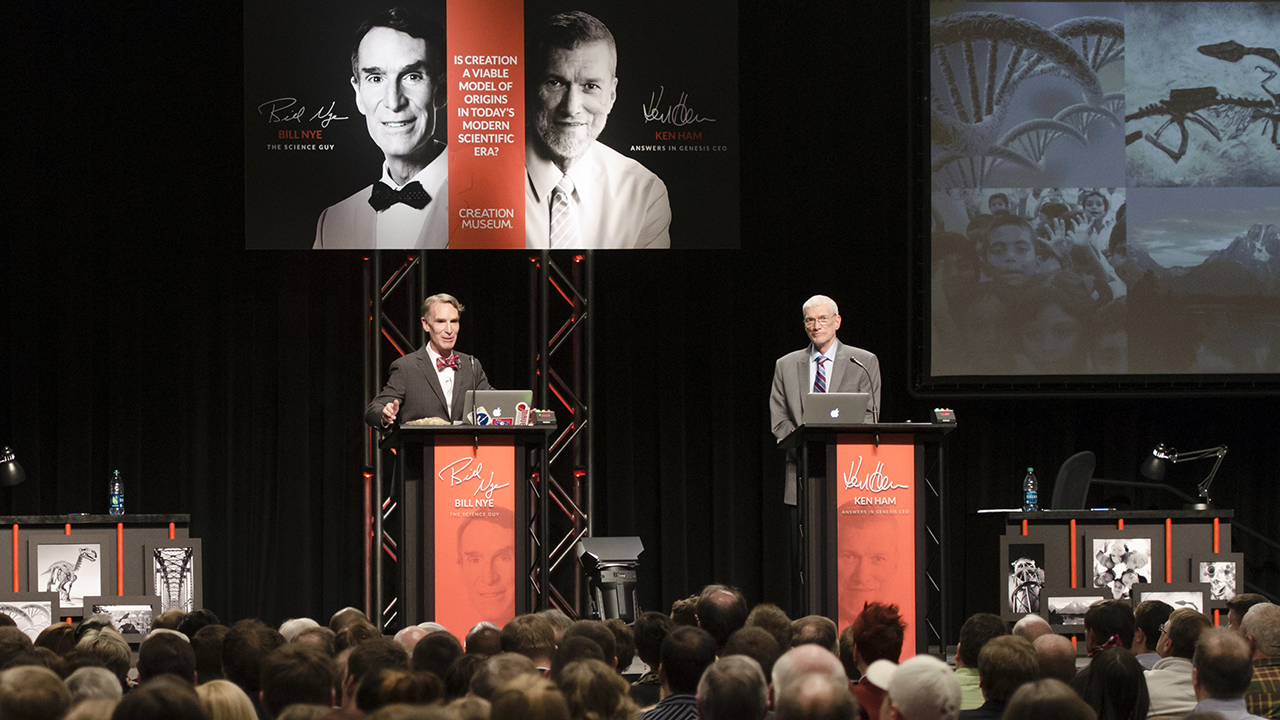

Partly due to these and other court decisions, opposition to teaching evolution itself evolved, with opponents changing their goals and tactics. In the first decade of the 21st century, for instance, some local and state school boards mandated the teaching of what they argued were scientific alternatives to evolution – notably the concept of “intelligent design,” which posits that life is too complex to have developed without the intervention of an outside, possibly divine, force. While rejected by most scientists as creationism cloaked in scientific language, supporters of intelligent design cite what they call “irreducibly complex” systems (such as the eye or the process by which blood clots) as proof that Darwinian evolution is not an adequate explanation for the development of life.

But efforts to inject intelligent design into public school science curricula met the same fate as creation science had decades earlier. Once again, courts ruled that intelligent design is a religious argument, not science, and thus couldn’t be taught in public schools. Other efforts to require schools to teach critiques of evolution or to mandate that students listen to or read evolution disclaimers also were struck down.

In the years following these court decisions, there have been new efforts in Texas, Tennessee, Kansas and other states to challenge the presence of evolutionary theory in public school science curricula. For instance, in 2017, the South Dakota Senate passed legislation that would allow teachers in the state’s public schools to present students with both the strengths and weaknesses of scientific information. The measure, which critics claimed was clearly aimed at critiquing evolution, ultimately stalled in the state’s House of Representatives. And in 2018, an internal review at the Arizona State Board of Education led to an unsuccessful effort to dilute references to evolution in the state’s science standards.

For more information about how Pew Research Center asks the U.S. public about their views on evolution, see “The Evolution of Pew Research Center’s Survey Questions About the Origins and Development of Life on Earth” and “How highly religious Americans view evolution depends on how they’re asked about it.”

Title photo: Famed attorney Clarence Darrow makes a point at the “Scopes Monkey Trial” in 1925. Darrow defended teacher John Scopes, who had run afoul of Tennessee’s law against teaching evolution in public schools. (Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)