The new, 116th Congress includes the first two Muslim women ever to serve in the House of Representatives, and is, overall, slightly more religiously diverse than the prior Congress.1

There has been a 3-percentage-point decline in the share of members of Congress who identify as Christian – in the 115th Congress, 91% of members were Christian, while in the 116th, 88% are Christian. There are also four more Jewish members, one additional Muslim and one more Unitarian Universalist in the new Congress – as well as eight more members who decline to state their religious affiliation (or lack thereof).

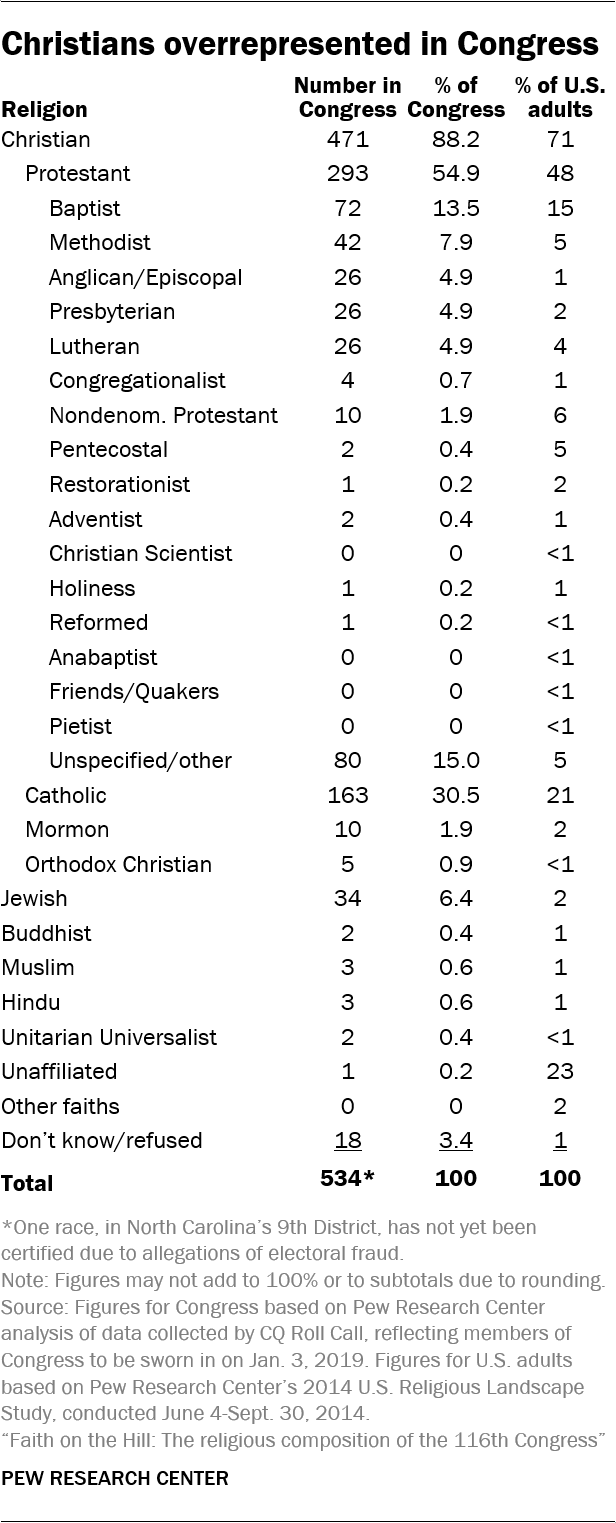

While the number of self-identified Christians in Congress has ticked down, Christians as a whole – and especially Protestants and Catholics – are still overrepresented in proportion to their share in the general public. Indeed, the religious makeup of the new, 116th Congress is very different from that of the United States population.

Within Protestantism, certain groups are particularly numerous in the new Congress, including Methodists, Anglicans/Episcopalians, Presbyterians and Lutherans. Additionally, Protestants in the “unspecified/other” category make up just 5% of the U.S. public, but 15% of Congress.2 By contrast, some other Protestant groups are underrepresented, including Pentecostals (5% of the U.S. public vs. 0.4% of Congress).

But by far the largest difference between the U.S. public and Congress is in the share who are unaffiliated with a religious group. In the general public, 23% say they are atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” In Congress, just one person – Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., who was recently elected to the Senate after three terms in the House – says she is religiously unaffiliated, making the share of “nones” in Congress 0.2%.

When asked about their religious affiliation, a growing number of members of Congress decline to specify (categorized as “don’t know/refused”). This group – all Democrats – numbers 18, or 3% of Congress, up from 10 members (2%) in the 115th Congress. Their reasons for this decision may vary. But one member in this category, Rep. Jared Huffman, D-Calif., announced in 2017 that he identifies as a humanist and says he is not sure God exists. Huffman remains categorized as “don’t know/refused” because he declined to state his religious identity in the CQ Roll Call questionnaire used to collect data for this report.3

These are some of the findings from an analysis by Pew Research Center of CQ Roll Call data on the religious affiliations of members of Congress, gathered through questionnaires and follow-up phone calls to members’ and candidates’ offices.4 The CQ questionnaire asks members what religious group, if any, they belong to. It does not attempt to measure their religious beliefs or practices. The Pew Research Center analysis compares the religious affiliations of members of Congress with the Center’s survey data on the U.S. public.5

Religious makeup of new Congress similar to that of previous class

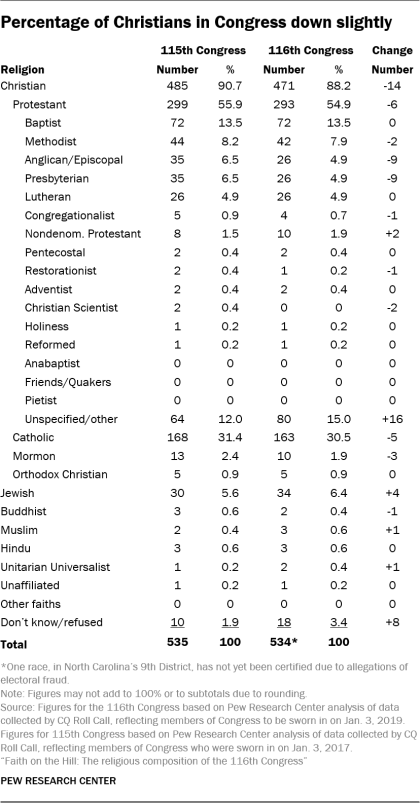

While the overall composition of the new Congress is similar to that of the previous Congress – roughly nine-in-ten members of each identified as Christian – the 116th Congress has 14 fewer Christians than the 115th, and 20 fewer Christians than the 114th Congress (2015-2016).

While the overall composition of the new Congress is similar to that of the previous Congress – roughly nine-in-ten members of each identified as Christian – the 116th Congress has 14 fewer Christians than the 115th, and 20 fewer Christians than the 114th Congress (2015-2016).

Anglicans/Episcopalians and Presbyterians experienced the largest losses in the 116th Congress, which has nine fewer members in each of these groups compared with the previous Congress. Methodists, Congregationalists, Restorationists and Christian Scientists also lost at least one seat; there are no longer any Christian Scientists in Congress.

Some Protestant denominational families now have more members in the new Congress, led by those in the “unspecified/other” category, which gained 16 seats, bringing the total number in this category to 80. Among members of Congress, “unspecified/other” Protestants include those who say they are Christian, evangelical Christian, evangelical Protestant or Protestant, without specifying a denomination. By contrast, nondenominational Protestants, who also gained two seats (going from eight to 10), are Christians who specifically describe themselves as nondenominational.

There are five fewer Catholics and three fewer Mormons in the new Congress. There has been no change in the number of Orthodox Christians (five seats in both the new and prior Congress).

Among non-Christians, four additional Jewish members bring the Jewish share of the new Congress to 6% – three times the share of Jews in the general public (2%). Additionally, Unitarian Universalists gained one seat.

Muslim women join the new Congress for the first time – Michigan Democrat Rashida Tlaib and Minnesota Democrat Ilhan Omar. They join Andre Carson, a Muslim Democrat from Indiana, in the House, bringing the number of Muslims in the new Congress to three – one more than in the 115th Congress. (Omar represents Minnesota’s 5th district – replacing Keith Ellison, who was the first Muslim elected to Congress in 2006.)

The number of Hindus in Congress is holding steady at three. All of the Hindus from the 115th Congress are returning for the 116th: Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif.; Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, D-Ill.; and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii.

The number of Buddhists in Congress has dropped by one. Colleen Hanabusa, D-Hawaii, decided to run for governor in Hawaii rather than seek re-election in the House. (She was ultimately unsuccessful in her gubernatorial campaign.) Georgia Democratic Rep. Hank Johnson and Hawaii Democratic Sen. Mazie K. Hirono, both Buddhist members of the previous Congress, are returning for the 116th.

Sinema remains the sole member of Congress who publicly identifies as religiously unaffiliated, although there has been an increase of eight members in the “don’t know/refused” category.

Differences by chamber

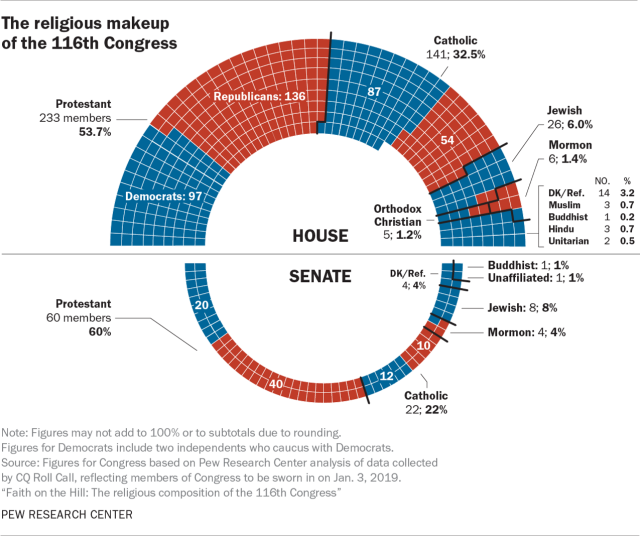

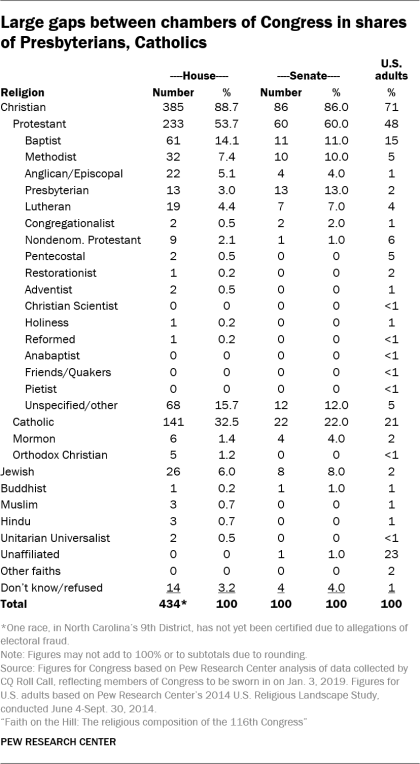

Christians make up large majorities in both chambers. In fact, Protestants alone form majorities in both the House (54%) and the Senate (60%). For the most part, there are only modest differences between the chambers within the Protestant denominational families, except when it comes to Presbyterians: There are 13 Presbyterians in each chamber, making up 13% of the Senate and just 3% of the House.

Christians make up large majorities in both chambers. In fact, Protestants alone form majorities in both the House (54%) and the Senate (60%). For the most part, there are only modest differences between the chambers within the Protestant denominational families, except when it comes to Presbyterians: There are 13 Presbyterians in each chamber, making up 13% of the Senate and just 3% of the House.

By contrast, Catholics make up a larger share of the lower chamber than the upper chamber: There are 141 Catholics in the House (32%) and 22 in the Senate (22%).

The Senate gains its first member to identify as religiously unaffiliated: Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., joins the Senate from the House, where she was the first unaffiliated member in that chamber.6

All of the Hindus and Muslims (three each) are in the House, along with both Unitarians. The two Buddhists in the 116th are split between the chambers. Jewish members make up a slightly larger proportion of the Senate than the House (8% vs. 6%).

The number of members who prefer not to specify a religious affiliation doubled in the House between the 115th Congress and the 116th – they now number 14. In the Senate, there are four members who do not specify a religion, up from three who said this in the previous Congress.

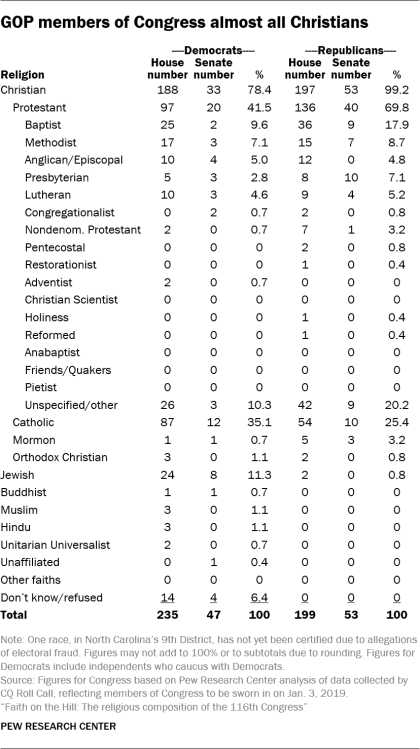

Differences by party

In the 116th Congress, just two of the 252 GOP members do not identify as Christian: Reps. Lee Zeldin, R-N.Y., and David Kustoff, R-Tenn., are Jewish.7

In the 116th Congress, just two of the 252 GOP members do not identify as Christian: Reps. Lee Zeldin, R-N.Y., and David Kustoff, R-Tenn., are Jewish.7

By contrast, 61 of the 282 Democrats do not identify as Christian. More than half of the 61 are Jewish (32), and 18 decline to specify a religious affiliation. Congressional Democrats also include Hindus (3), Muslims (3), Buddhists (2), Unitarian Universalists (2) and one religiously unaffiliated member. 8

Christians remain overrepresented in both parties’ congressional delegations compared with their coalitions in the general public. While 78% of Democrats in Congress identify as Christians, among registered voters in the broader U.S. adult population, the share of Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party who identify as Christians is just 57%.9

Among Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party in the general public, 82% of registered voters are Christians, compared with about 99% of Republicans in Congress. Put another way, 18% of Republican voters are not Christian, which stands in stark contrast to the 0.8% of congressional Republicans who are not Christian.

Republican members of Congress are more likely than Democratic members to identify as Protestants (70% vs. 41%). Democrats in Congress, by contrast, are more likely to be Catholic – 35% of congressional Democrats are Catholic, compared with 25% of Republicans in Congress.

There has been a rapid shift in the partisan composition of Catholics in the House. In the 114th Congress (2015-2016), the numbers of Catholic Democrats and Catholic Republicans in the House were almost identical (68 vs. 69), and the figures remained similar in the 115th Congress (74 Catholic Democrats vs. 70 Catholic Republicans in the House). But the new Congress has 33 more Catholic Democrats than Catholic Republicans in the House (87 vs. 54).

First-time members

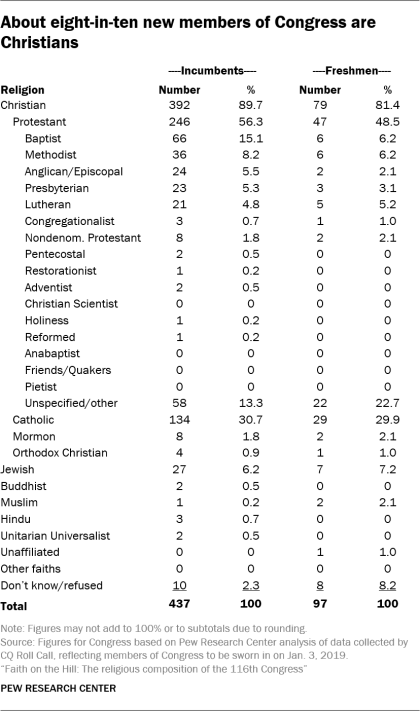

The new, 116th Congress has the largest freshman class since 2011 – 97 new members join 437 incumbents.10

The new, 116th Congress has the largest freshman class since 2011 – 97 new members join 437 incumbents.10

Of the new members, fully 81% identify as Christians. While this is lower than the Christian share of incumbents, it is still higher than the share of U.S. adults who are Christian (71%).

About half of freshmen are Protestants (49%), and three-in-ten are Catholic (30%). Among the Protestants in the freshman class, 23% are in the “unspecified/other” Protestant category. Rounding out the Christian freshmen are two Mormons (Democratic Rep. Ben McAdams and Republican Sen. Mitt Romney, both of Utah) and one Orthodox Christian (Rep. Chris Pappas, D-N.H.).

Among the newcomers, there also are seven Jewish members and eight who prefer not to specify their religion, as well as two Muslims and an unaffiliated member (Sinema is counted as a freshman because she is moving from the House to the Senate).

Looking back

Over the 11 congresses for which Pew Research Center has data, the 116th has the lowest number of both Christians (471) and Protestants (293). The 116th Congress also has the fewest Mormon members in at least a decade – members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints now number 10, a low over the last six congresses.

Catholics have held steady at 31% over the last four congresses, although there are now many more Catholics in Congress than there were in the first Congress for which Pew Research Center has data (19% in the 87th Congress, which began in 1961). The share of Jewish members also has increased markedly since the early ’60s.

CORRECTION (Jan. 3, 2019): A previous version of this report’s dataset had the wrong member of Congress listed for California’s 21st District. Freshman Rep. TJ Cox, a Catholic Democrat, represents the district. The report and detailed tables have been updated to reflect this correction.