In the United States, religious congregations have been graying for decades, and young adults are now much less religious than their elders. Recent surveys have found that younger adults are far less likely than older generations to identify with a religion, believe in God or engage in a variety of religious practices.

But this is not solely an American phenomenon: Lower religious observance among younger adults is common around the world, according to a new analysis of Pew Research Center surveys conducted in more than 100 countries and territories over the last decade.

Although the age gap in religious commitment is larger in some nations than in others, it occurs in many different economic and social contexts – in developing countries as well as advanced industrial economies, in Muslim-majority nations as well as predominantly Christian states, and in societies that are, overall, highly religious as well as those that are comparatively secular.

For example, adults younger than 40 are less likely than older adults to say religion is “very important” in their lives not only in wealthy and relatively secular countries such as Canada, Japan and Switzerland, but also in countries that are less affluent and more religious, such as Iran, Poland and Nigeria.

While this pattern is widespread, it is not universal. In many countries, there is no statistically significant difference in levels of religious observance between younger and older adults. In the places where there is a difference, however, it is almost always in the direction of younger adults being less religious than their elders.

Same pattern seen over multiple measures of religious commitment

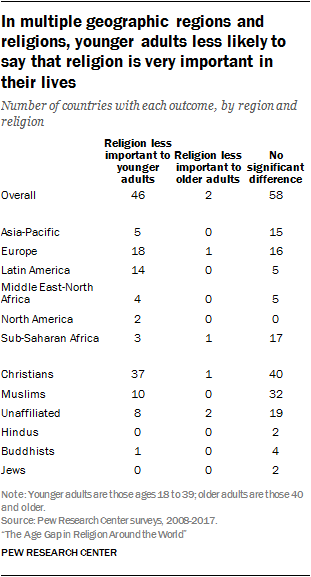

Overall, adults ages 18 to 39 are less likely than those ages 40 and older to say religion is very important to them in 46 out of 106 countries surveyed by Pew Research Center over the last decade. In 58 countries, there are no significant differences between younger and older adults on this question. And just two countries – the former Soviet republic of Georgia and the West African country of Ghana – have younger adults who are, on average, more religious than their elders. (For theories about why younger adults often are less religious, see Chapter 1. For a discussion of some of these exceptions, see the sidebar in Chapter 2.)

Similar patterns also are found using three other standard measures of religious identification and commitment: affiliation with a religious group, daily prayer and weekly worship attendance.

In 41 countries, adults under 40 are significantly less likely than their elders to have a religious affiliation, while in only two countries (Chad and Ghana) are younger adults more likely to identify with a religious group. In 63 countries, there is no statistically significant difference in affiliation rates.

Younger adults are less likely to say they pray daily in 71 of 105 countries and territories for which Pew Research Center survey data are available, while they are more likely to pray daily in two countries (Chad and Liberia). And adults under 40 are less likely to attend religious services on a weekly basis in 53 of 102 countries; the opposite is true in just three countries (Armenia, Liberia and Rwanda).

While the number of countries with a significant age gap shows how widespread this pattern is, it does not give a sense of the magnitude of the differences between older and younger adults on these measures.

In many countries, the gaps are relatively small. Indeed, the average gap between younger adults and older adults across all the countries surveyed is 5 percentage points for affiliation, 6 points for importance of religion, 6 points for worship attendance and 9 points for prayer.

But a substantial number of countries have much bigger differences. There are gulfs of at least 10 percentage points between the shares of older and younger adults who identify with a religious group in more than two dozen countries – mostly with predominantly Christian populations in Europe and the Americas. For example, the share of U.S. adults under age 40 who identify with a religious group is 17 percentage points lower than the share of older adults who are religiously affiliated. The gap is even larger in neighboring Canada (28 points). And there are double-digit age gaps in affiliation in countries as far flung as South Korea (24 points), Uruguay (18 points) and Finland (17 points).

A note on averages

To help make sense of an enormous pool of data, this report sometimes cites global averages of country-level data. In calculating the averages, each country is weighted equally, regardless of population size. Global averages, therefore, should be interpreted as the average finding among all countries surveyed, not as population-weighted averages representing all people around the world.

Differences among regions, religions

Age gaps are more common in some geographic regions than others. For instance, in 14 out of 19 countries and territories surveyed in Latin America and the Caribbean, adults under age 40 are significantly less likely than their elders to say religion is very important in their lives. This is also the case in about half of the European countries surveyed (18 out of 35), and in both countries in North America (the U.S. and Canada; Mexico is included in the figures for Latin America).

Age gaps are more common in some geographic regions than others. For instance, in 14 out of 19 countries and territories surveyed in Latin America and the Caribbean, adults under age 40 are significantly less likely than their elders to say religion is very important in their lives. This is also the case in about half of the European countries surveyed (18 out of 35), and in both countries in North America (the U.S. and Canada; Mexico is included in the figures for Latin America).

On the other hand, in sub-Saharan Africa, where overall levels of religious commitment are among the highest in the world, there is no significant difference between older and younger adults in terms of the importance of religion in 17 out of 21 countries surveyed.

Age gaps are also more common within some religious groups than in others. For example, religion is less important to younger Christian adults in nearly half of all the countries around the world where sample sizes are large enough to allow age comparisons among Christians (37 out of 78). For Muslims, this is the case in about one-quarter of countries surveyed (10 out of 42). Among Buddhists, younger adults are significantly less religious in just one country (the United States) out of five countries for which data are available. There is no age gap by this measure among Jews in the U.S. or Israel, or among Hindus in the U.S. or India.1

Do age gaps mean the world is becoming less religious?

The widespread pattern in which younger adults tend to be less religious than older adults may have multiple potential causes. Some scholars argue that people naturally become more religious as they age; to others, the age gap is a sign that parts of the world are secularizing (i.e., becoming less religious over time). (For a detailed discussion of theories about age gaps and secularization, see Chapter 1.)

But even if parts of the world are secularizing, it is not necessarily the case that the world’s population, overall, is becoming less religious. On the contrary, the most religious areas of the world are experiencing the fastest population growth because they have high fertility rates and relatively young populations.

Previously published projections show that if current trends continue, countries with high levels of religious affiliation will grow fastest. The same is true for levels of religious commitment: The fastest population growth appears to be occurring in countries where many people say religion is very important in their lives.

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center analysis of surveys collected over the last decade in 106 countries. The data analyzed in this report come from 13 different Pew Research Center studies, including annual Global Attitudes Surveys as well as major studies on religion in sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East and other countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America; the United States; Central and Eastern Europe; and Western Europe.

The number of countries analyzed varies by measure and type of comparison. While data are available for as many as 106 countries depending on the measure, the number of countries with reliable data on a particular religious group depends on the size of that group in each country’s sample. For example, there are sufficient data to gauge the importance of religion among Christians in 84 countries, and the sample sizes are large enough to compare responses among older and younger Christians in 78 of those 84 countries.

Another limitation is that the measures of religious observance contained in many surveys around the world and analyzed in this report may not be equally suitable for all religious groups. In particular, rates of prayer and attendance at worship services are generally seen as reliable indicators of religious observance within Abrahamic faiths (Christianity, Islam and Judaism), but they may not be as applicable for Buddhism, Hinduism and other Eastern religions. Because of these disparities, this report does not seek to compare levels of religious commitment between the world’s major religions (e.g., to compare Christians with Buddhists or Muslims). Rather, the primary focus is on age differences within religious groups and within countries or geographic regions (e.g., comparing younger Christians with older Christians, or younger Indonesians with older Indonesians).

This study, produced with funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, a broader effort to understand religious change, including the demographic patterns shaping religion around the world. Previous reports have focused on gender and religion, religion and education and population growth projections for major world religions.

The rest of this report looks in more detail at both age gaps in religious commitment (Chapter 2) and overall levels of religious commitment around the world (Chapter 3), by four standard measures: religious affiliation, importance of religion, attendance and prayer. Appendixes detail the methodology and sources used, and include tables that show each of the four measures for every country surveyed with data for overall levels of religious commitment, figures for adults over and under 40, age gaps for the total population and age gaps by religious group. But, first, Chapter 1 examines theories about why levels of religious observance vary so markedly across different age groups and different parts of the world.