Muslims in America: Immigrants and those born in U.S. see life differently in many ways

The immigrant experience is deeply ingrained in the fabric of Islam in America. Most U.S. Muslim adults (58%) hail from other parts of the globe, their presence in America owing largely to the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act that lowered barriers to immigration from Asia, Africa and other regions outside Europe.

But the U.S.-born share of the American Muslim population is also considerable (42%). It consists of descendants of Muslim immigrants, converts to Islam (many of them black) and descendants of converts.

When Pew Research Center surveyed American Muslim adults in 2017, the findings revealed important similarities between foreign-born and U.S.-born Muslims. For example, immigrants and U.S.-born Muslims engage in religious practices at about the same levels. At the same time, there are also important differences. Immigrants tend to have secured a stronger socioeconomic foothold than U.S.-born Muslims, and they generally express more positive opinions about their place in America.

Diversity in origin, race

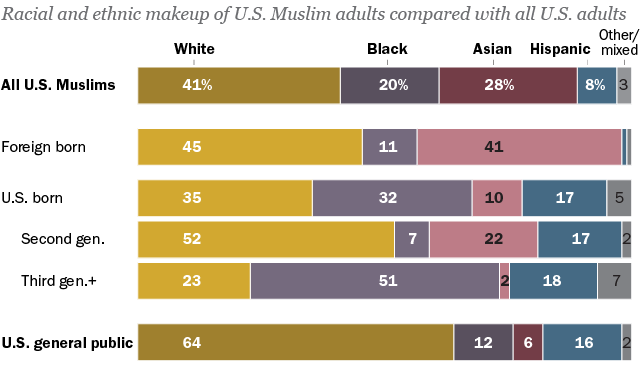

Both the immigrant and U.S.-born Muslim populations are racially and ethnically diverse, though in different ways. A large share of foreign-born Muslims are Asian, while many U.S.-born Muslims are black or Hispanic. And substantial shares of both foreign-born and U.S.-born Muslims identify as white, a category that also includes people who identify racially as Arab, Middle Eastern or Persian.

There’s no single racial or ethnic majority within the Muslim community.

Click to play video

Muslim immigrants in the United States, roughly half of whom (56%) have arrived since the year 2000, come from a wide array of countries, and no single region or country of origin accounts for a majority of them. In total, immigrant respondents in Pew Research Center’s 2017 survey of U.S. Muslims named 75 different countries of origin. And this is reflected in their racial and ethnic diversity: No single racial or ethnic group accounts for a majority among Muslim immigrants, with 45% identifying as white and a similar share (41%) identifying as Asian.

Muslim adults who were born in the U.S. to at least one immigrant parent — that is, those in the second generation — are more likely to be categorized as white (52%) than as any other race or ethnicity. About four-in-ten (44%), have at least one parent who emigrated from the Middle East or North Africa.

Among Muslims in the third generation or higher — people born in the U.S., and whose parents also were born in the U.S. — about half (51%) say they are black, while very few (2%) are Asian. Those in the third generation or higher also are much more likely to be converts: Two-thirds of Muslims in this group have not always been Muslim. By contrast, eight-in-ten second-generation U.S. Muslims (81%) and nearly all immigrant Muslims (95%) have been Muslim since childhood.

In all, second-generation Americans make up 18% of the U.S. Muslim adult population, while Muslims who have been in the United States for three or more generations make up an additional 24%.

Similarities in religious identity and national pride

Immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims exhibit similar levels of religious observance. People in both groups are about equally likely to attend religious services at least once a week, to say that eating halal food is essential to being a Muslim, and to say they fast during Ramadan. And similar shares say there is something about their “appearance, voice or clothing” that might identify them as Muslim; immigrant Muslim women are about as likely as U.S.-born Muslim women to regularly wear head coverings in public.

Muslims are also quite diverse in terms of their religious beliefs and practices.

Click to play video

The similarities between immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims also include high levels of pride in their religious and national identities. Large majorities in both groups say they are proud to be Muslim – and also proud to be American.

The American experience has been, for the vast majority of Muslims, an experience that has been empowering … so there’s a lot of pride.

Click to play video

Both immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims are about as likely as the general U.S. population to say they are proud to be American. And they express pride in their religious identity at about the same rate as U.S. Christians.

On social, economic issues, immigrants more satisfied, faring better

In significant ways, however, the Muslim American experience has been different for immigrants than for the U.S. born.

For example, by several measures often used to measure financial well-being and stability, immigrant Muslims are better off, collectively, than U.S.-born Muslims. Immigrant Muslims are roughly twice as likely as Muslims who were born in the United States to own a home and have a college degree.

Some of these differences are linked with broader racial patterns in the general population. For example, black Americans in general are less likely than people of other races to have a college degree or to make at least $100,000 in household income — and black people make up a much larger share of U.S.-born Muslims than of Muslim immigrants.

As a group, Muslim immigrants are different in these ways from U.S. immigrants overall, who tend to make lower salaries and are no more likely to have a college degree than people who were born in the United States.

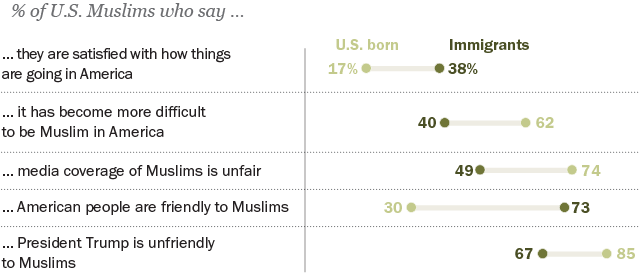

Compared with U.S.-born Muslims, immigrant Muslims are more likely to express positive feelings about life in America. For example, foreign-born Muslims are more likely than U.S.-born Muslims to say they are satisfied with how things are going in the country and to believe that other Americans are friendly to Muslims. They also are less likely than U.S.-born Muslims to say that media coverage of Muslims is unfair, that being a Muslim in America has become more difficult in recent years, and that President Trump is unfriendly to Muslim Americans.

I think the older generation of immigrants … are definitely more quiet on these issues … versus me, I’ve been here, I was born here, I’m here to change it and make it better.

Click to play video

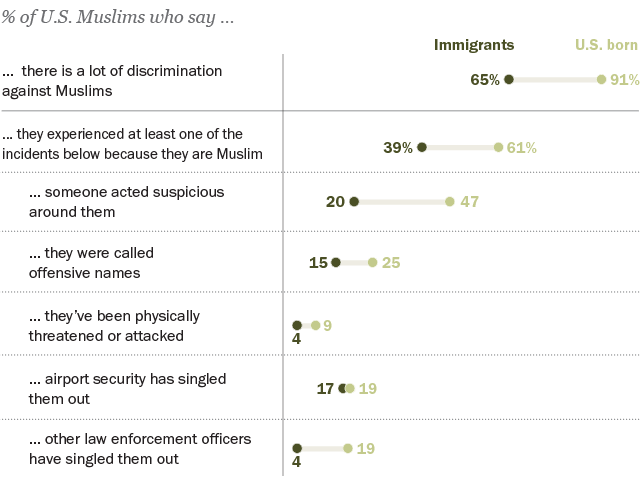

When asked about anti-Muslim discrimination, U.S.-born Muslims are more likely than immigrant Muslims to say there is a lot of it in America, as well as to say they personally have experienced it in one or more forms. And they are more likely to believe a lot of discrimination exists in the United States against black people, Hispanics, and gays and lesbians. Again, this may be connected – at least in part – to the views of black people in general, who are especially likely to perceive high levels of discrimination.

The experience of it, it’s just like being an African American. And you’re Muslim.

Click to play video

Mostly similar on politics, with some differences

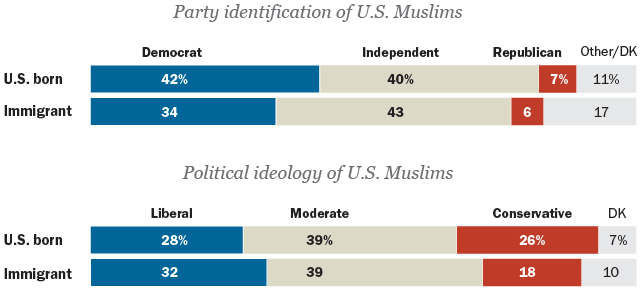

Despite these differences, immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims have much in common when it comes to politics. Each group is divided in roughly similar ways along the American political and ideological spectrums. Both U.S.-born and immigrant Muslims are far likelier to be Democrats than Republicans. And, ideologically, equal shares of both groups identify as moderates.

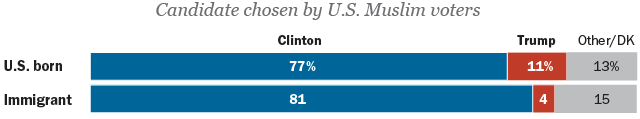

In addition, during the 2016 presidential election, both immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims overwhelmingly backed Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton over the Republican, Donald Trump. In the two previous Pew Research Center surveys of U.S. Muslims, most immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims also said they voted for the Democratic candidates, Barack Obama in 2008 and John Kerry in 2004, over Republicans John McCain and George W. Bush. In 2004, though, immigrant Muslims were more likely than U.S.-born Muslims to vote for Bush (21% vs. 8%).

Immigrant Muslims are less likely than U.S.-born Muslims to say they cast ballots in the 2016 election (36% vs. 54%). However, among U.S. Muslim immigrants who are citizens (and therefore eligible to vote), 53% say they voted — virtually identical to the share among U.S.-born Muslims.

Overall, seven-in-ten immigrant Muslims are U.S. citizens (70%). That’s a higher rate seen among U.S. immigrants overall (51%), according to the Census Bureau’s 2016 Current Population Survey. When the calculation excludes immigrants who arrived in the United States within five years of the 2017 survey results (since it typically takes at least five years of permanent residence to become a naturalized citizen), the rate of immigrant Muslim citizenship is even higher – 87%, compared with 55% among all U.S. immigrants.

For a more comprehensive political, religious and demographic portrait of Muslim Americans, see the full report on the survey. Watch the short documentary, “Being Muslim in the U.S.,” for a look inside the beliefs and attitudes of Muslims in America based on the survey.