As long-simmering debates continue over how American society should commemorate the Christmas holiday, a new Pew Research Center survey finds that most U.S. adults believe the religious aspects of Christmas are emphasized less now than in the past – even as relatively few Americans are bothered by this trend. In addition, a declining majority says religious displays such as nativity scenes should be allowed on government property. And compared with five years ago, a growing share of Americans say it does not matter to them how they are greeted in stores and businesses during the holiday season – whether with “merry Christmas” or a less-religious greeting like “happy holidays.”

Not only are some of the more religious aspects of Christmas less prominent in the public sphere, but there are signs that they are on the wane in Americans’ private lives and personal beliefs as well. For instance, there has been a noticeable decline in the percentage of U.S. adults who say they believe that biblical elements of the Christmas story – that Jesus was born to a virgin, for example – reflect historical events that actually occurred. And although most Americans still say they mark the occasion as a religious holiday, there has been a slight drop in recent years in the share who say they do this.

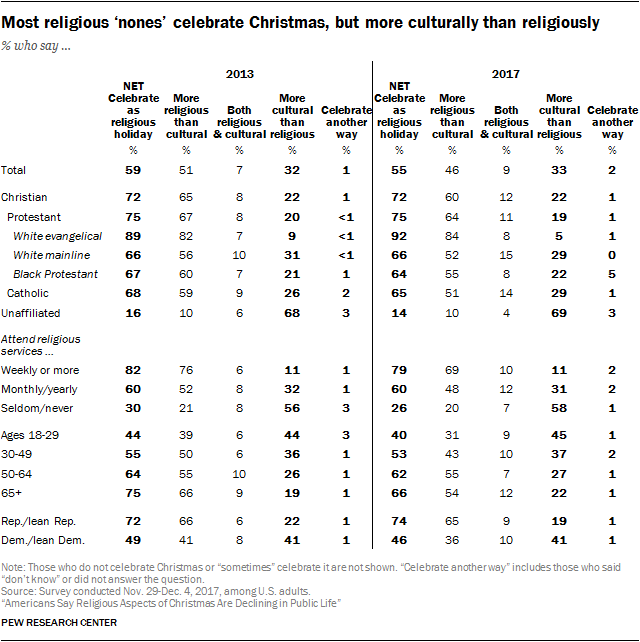

Currently, 55% of U.S. adults say they celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, including 46% who see it as more of a religious holiday than a cultural holiday and 9% who celebrate Christmas as both a religious and a cultural occasion. In 2013, 59% of Americans said they celebrated Christmas as a religious holiday, including 51% who saw it as more religious than cultural and 7% who marked the day as both a religious and a cultural holiday.

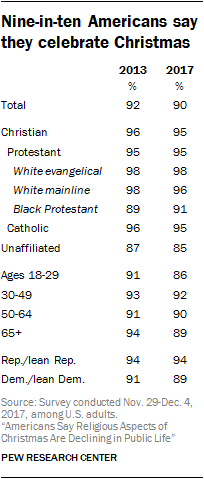

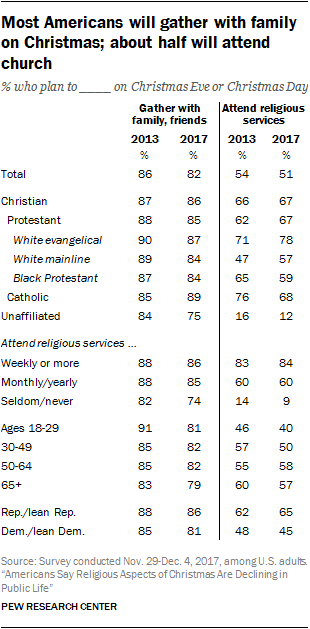

To be sure, while the public’s commemoration of Christmas may have less of a religious component now than in the past, the share of Americans who say they celebrate Christmas in some way has hardly budged at all. Nine-in-ten U.S. adults say they celebrate the holiday, which is nearly identical to the share who said this in 2013. About eight-in-ten will gather with family and friends. And half say they plan to attend church on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day, little changed since 2013, the last time Pew Research Center asked the question.

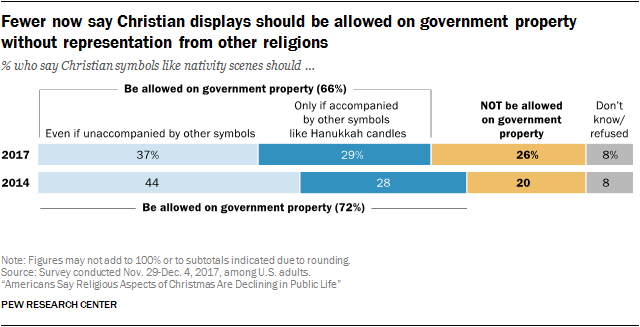

But some of the ways Americans think about and commemorate Christmas appear to be moving in a more secular direction. For instance, while two-thirds of Americans continue to say that Christian displays like nativity scenes should be permitted on government property during the holidays, the share who say these displays should be allowed on their own (unaccompanied by symbols of other faiths) has declined by 7 percentage points since 2014. Meanwhile, the share of Americans who believe no religious displays should be permitted on government property has grown from 20% to 26% over the past three years.

For more than a decade, conservative commentators and others – perhaps most prominently former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly – have been warning about what they perceive as a “War on Christmas,” or an effort to remove religious elements of the holiday from the public sphere. Conflicts over related issues have continued this year, and Donald Trump has repeatedly said, both during the 2016 presidential campaign and since his election, that Americans will be “saying ‘merry Christmas’ again” during his presidency.

For more than a decade, conservative commentators and others – perhaps most prominently former Fox News host Bill O’Reilly – have been warning about what they perceive as a “War on Christmas,” or an effort to remove religious elements of the holiday from the public sphere. Conflicts over related issues have continued this year, and Donald Trump has repeatedly said, both during the 2016 presidential campaign and since his election, that Americans will be “saying ‘merry Christmas’ again” during his presidency.

A rising share of Americans say they do not have a preference about how they are greeted in stores during the holiday season, while a declining percentage prefer to have stores greet them with “merry Christmas.” Today, fully half of the U.S. public (52%) says that a business’ choice of holiday greeting does not matter to them, while roughly a third (32%) prefers for stores and businesses to greet customers with “merry Christmas” during the holidays. When this question was first asked over a decade ago, and then again in 2012, roughly equal shares expressed a preference for “merry Christmas” and said it didn’t matter.

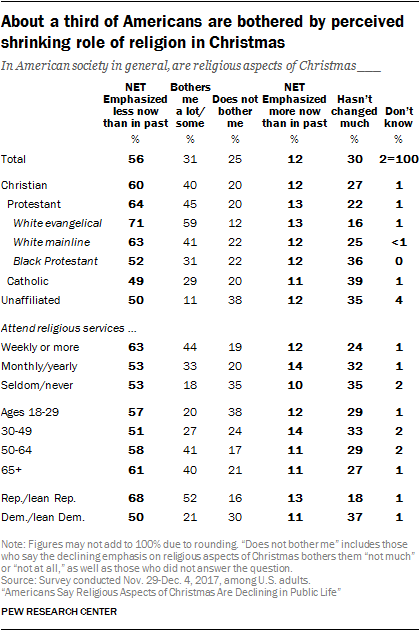

When asked directly, most respondents in the new poll say they think religious aspects of Christmas are emphasized less in American society today than in the past. But relatively few Americans both perceive this trend and are bothered by it. Overall, 31% of adults say they are bothered at least “some” by the declining emphasis on religion in the way the U.S. commemorates Christmas, including 18% who say they are bothered “a lot” by this. But the remaining two-thirds of the U.S. public either is not bothered by a perceived decline in religion in Christmas or does not believe that the emphasis on the religious elements of Christmas is waning.

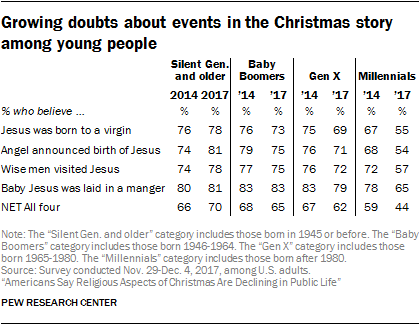

Among the topics probed by the new survey, one of the most striking changes in recent years involves the share of Americans who say they believe the birth of Jesus occurred as depicted in the Bible. Today, 66% say they believe Jesus was born to a virgin, down from 73% in 2014. Likewise, 68% of U.S. adults now say they believe that the wise men were guided by a star and brought gifts for baby Jesus, down from 75%. And there are similar declines in the shares of Americans who believe that Jesus’ birth was heralded by an angel of the Lord and that Jesus was laid in a manger as an infant.

Among the topics probed by the new survey, one of the most striking changes in recent years involves the share of Americans who say they believe the birth of Jesus occurred as depicted in the Bible. Today, 66% say they believe Jesus was born to a virgin, down from 73% in 2014. Likewise, 68% of U.S. adults now say they believe that the wise men were guided by a star and brought gifts for baby Jesus, down from 75%. And there are similar declines in the shares of Americans who believe that Jesus’ birth was heralded by an angel of the Lord and that Jesus was laid in a manger as an infant.

Overall, 57% of Americans now believe in all four of these elements of the Christmas story, down from 65% in 2014.

Religious ‘nones’ explain much, but not all, of decline in belief in Christmas story

The religiously unaffiliated – those who identify religiously as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” and who are sometimes also referred to as religious “nones” – are much less likely than Christians to express belief in the biblical Christmas story. And, in recent years, “nones” have become even less likely to believe in it, contributing to the public’s overall decline in belief in the biblical depiction of Jesus’ birth. (Religious “nones” also have been growing as a share of the U.S. population, although the religiously unaffiliated share of respondents in the December 2017 survey is similar in size to the unaffiliated share of the December 2014 sample.)

The religiously unaffiliated – those who identify religiously as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular,” and who are sometimes also referred to as religious “nones” – are much less likely than Christians to express belief in the biblical Christmas story. And, in recent years, “nones” have become even less likely to believe in it, contributing to the public’s overall decline in belief in the biblical depiction of Jesus’ birth. (Religious “nones” also have been growing as a share of the U.S. population, although the religiously unaffiliated share of respondents in the December 2017 survey is similar in size to the unaffiliated share of the December 2014 sample.)

At the same time, the new study finds a small but significant decline in the share of Christians who believe in the Christmas narrative contained in the Bible. To be sure, large majorities of Christians still believe in key elements of the nativity story as described in the Bible. But the shares of Christians who believe in the virgin birth, the visit of the Magi, the announcement of Jesus’ birth by an angel and the baby Jesus lying in the manger all have ticked downward in recent years. Overall, the share of Christians who believe in all four of these elements of the Christmas story has dipped from 81% in 2014 to 76% today. This decline has been particularly pronounced among white mainline Protestants (see below for details).

Partisan differences in views on Christmas in public life

The study finds clear divisions along party lines in questions about the way Christmas is observed in American culture. For example, about half of those who identify with or lean toward the Republican Party express a preference for hearing “merry Christmas” from stores and businesses, compared with 19% of Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party. By contrast, a majority of Democrats (61%) say “it doesn’t matter” when asked how they prefer to be greeted during the holidays; 38% of Republicans take this position. Democrats also are more likely than Republicans to prefer a less-religious greeting like “happy holidays” (20% vs. 7%).

The study finds clear divisions along party lines in questions about the way Christmas is observed in American culture. For example, about half of those who identify with or lean toward the Republican Party express a preference for hearing “merry Christmas” from stores and businesses, compared with 19% of Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party. By contrast, a majority of Democrats (61%) say “it doesn’t matter” when asked how they prefer to be greeted during the holidays; 38% of Republicans take this position. Democrats also are more likely than Republicans to prefer a less-religious greeting like “happy holidays” (20% vs. 7%).

A higher share of Republicans than Democrats express the view that the religious aspects of Christmas are emphasized less now than in the past (68% vs. 50%). And the partisan gap is even bigger when it comes to whether this perceived trend is seen as negative. Fully half of Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP say they are bothered “a lot” (32%) or “some” (20%) by a declining emphasis on the religious aspects of Christmas. Among Democrats, just one-in-five say they are bothered “a lot” (10%) or “some” (11%) by these changes.

There also are clear partisan divisions when it comes to the debate about religious displays on public property. Among Republicans, 54% say that Christian symbols, like nativity scenes, should be allowed on government property even if they are not accompanied by symbols from other faiths, while only half as many Democrats (27%) share this view.

Big differences in how generational cohorts mark the holidays

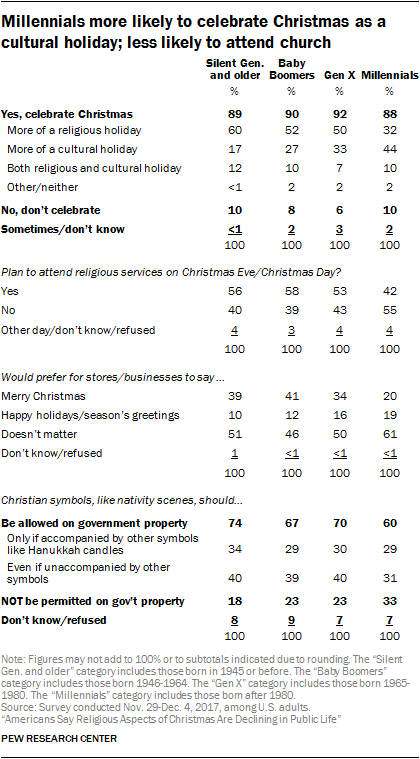

The survey finds large generational differences in the way Americans approach Christmas. Millennials, for example, are much less likely than older cohorts to say they celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, and more likely to say they celebrate it as a cultural holiday.

The survey finds large generational differences in the way Americans approach Christmas. Millennials, for example, are much less likely than older cohorts to say they celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, and more likely to say they celebrate it as a cultural holiday.

Similarly, while 42% of Millennials say they plan to attend church this Christmas, half or more of those in older generations say they will incorporate a trip to church into their Christmas celebration.

These generation gaps extend to questions about Christmas in public life. A majority of Millennials (61%) say they do not have a preference about how stores and businesses greet them during the holiday, while just 20% say they prefer for businesses to greet them with “merry Christmas” – significantly lower than the share of older cohorts who say this. And Millennials also are less likely than members of older generations to say it is acceptable to display Christian symbols on government property.

The survey also finds an important generational component to trends in beliefs about the Christmas story. Simply put, Millennials express lower levels of belief in the Christmas narrative than they did in 2014, and they are now significantly less likely than their elders to say that the Christmas story reflects events that actually occurred. This partly reflects the fact that there are fewer self-identified Christians among Millennials than among older generations. Even among Christians, however, Millennials are now significantly less likely than older adults as a whole to believe in all four elements of the Christmas story covered in the survey, which is a change since 2014.

The survey also finds an important generational component to trends in beliefs about the Christmas story. Simply put, Millennials express lower levels of belief in the Christmas narrative than they did in 2014, and they are now significantly less likely than their elders to say that the Christmas story reflects events that actually occurred. This partly reflects the fact that there are fewer self-identified Christians among Millennials than among older generations. Even among Christians, however, Millennials are now significantly less likely than older adults as a whole to believe in all four elements of the Christmas story covered in the survey, which is a change since 2014.

These are among the key findings from the latest Pew Research Center survey, conducted by telephone Nov. 29 to Dec. 4, 2017, among a representative sample of 1,503 adults nationwide. The rest of this report looks at the results of the survey in more detail, including trends over time and differences by religious affiliation and observance.

Christmas in public life

Smaller majority now says Christian displays on government property are acceptable

While most Christians (73%) continue to think displaying religious symbols on government property is acceptable during the Christmas season, Christians as a whole have become less supportive of this position over the last three years. The change is most pronounced among white evangelical Protestants, who are less likely, by 10 percentage points, to favor displaying Christian symbols on government property today (80%) than in 2014 (90%). By comparison with white evangelicals, the views of other Christian groups are more stable on this question.

Most white evangelical Protestants (57%) say they think it is OK for Christian symbols like nativity scenes to be displayed on government property even if the Christian symbols are not accompanied by imagery from other faiths. Smaller shares of black Protestants (41%), white mainline Protestants (39%) and Catholics (35%) are comfortable displaying only Christian symbols on government property, although similar shares of all three groups say such displays are acceptable if they are accompanied by religious symbols from other faiths.

Religious “nones” are divided in their views about religious displays on government property. Half think that displaying Christian symbols on government property is acceptable (including 24% who think such displays are OK by themselves and 27% who think they are only acceptable if accompanied by other religious symbols), while 45% say no religious symbols should be displayed on government property.

Most say religious aspects of Christmas emphasized less now than in past

Seven-in-ten white evangelical Protestants say that in American society, the religious aspects of Christmas are emphasized less today than in the past, and most (59%) say they find this at least somewhat bothersome. Nearly two-thirds of white mainline Protestants agree that the religious aspects of Christmas get less emphasis today than in the past, but compared with white evangelicals, they are less troubled by this development; 41% of white mainline Protestants say the declining emphasis on the religious aspects of Christmas bothers them “a lot” or “some.”

Seven-in-ten white evangelical Protestants say that in American society, the religious aspects of Christmas are emphasized less today than in the past, and most (59%) say they find this at least somewhat bothersome. Nearly two-thirds of white mainline Protestants agree that the religious aspects of Christmas get less emphasis today than in the past, but compared with white evangelicals, they are less troubled by this development; 41% of white mainline Protestants say the declining emphasis on the religious aspects of Christmas bothers them “a lot” or “some.”

Roughly half of Catholics (49%), religious “nones” (50%) and black Protestants (52%) say religion has a shrinking role in the way Christmas is celebrated in the U.S., but “nones” are less likely than other groups to be bothered by this trend.

While half or more of adults of all ages agree that emphasis on the religious aspects of Christmas has declined (compared with Christmases past), adults under 50 are significantly less likely than those ages 50 and older to say they find this bothersome.

One-third prefer for stores, businesses to use ‘merry Christmas,’ while half now say it doesn’t matter to them

One-third prefer for stores, businesses to use ‘merry Christmas,’ while half now say it doesn’t matter to them

Most white evangelical Protestants say they prefer for stores and other businesses to greet their customers by saying “merry Christmas” during the holidays. But evangelicals are somewhat less likely to express this view today (61%) compared with 2012 (70%).

Within every other major Christian tradition, there are at least as many people who say the holiday greetings used by stores and businesses don’t matter to them as there are who say they prefer “merry Christmas.” And among religious “nones,” fully 72% say the holiday greeting businesses use doesn’t much matter to them.

Christmas commemorations and beliefs

Religious and family elements of Christmas celebrations

Large majorities in every major Christian group say they celebrate Christmas. Even among religious “nones,” fully 85% say they celebrate the holiday.

Large majorities in every major Christian group say they celebrate Christmas. Even among religious “nones,” fully 85% say they celebrate the holiday.

There are sizable differences, though, in the way people from various religious groups think about the occasion. Perhaps not surprisingly, most Christians (72%) say they mark the day as a religious holiday, including 60% who celebrate as more of a religious holiday than a cultural occasion and 12% who mark it as both a religious holiday and a cultural holiday. The share of Christians who celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday – either solely religious or partly religious and partly cultural – ranges from 64% among black Protestants to 92% among white evangelical Protestants.

Among religious “nones,” however, seven-in-ten (69%) say they celebrate Christmas as more of a cultural holiday than a religious occasion, compared with just 10% who celebrate it as a more of a religious holiday and 4% who celebrate both the religious and cultural aspects.

The survey also finds that older adults are much more likely than younger people to celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday. And Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to observe Christmas as a religious holiday. About three-quarters of Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP say they celebrate Christmas as a religious holiday, compared with just 46% of Democrats.

This year, roughly eight-in-ten Americans (82%) say they intend to gather with family and friends on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day, down slightly since 2013 (86%). Large majorities in every religious group, ranging from 75% of religious “nones” to 89% of Catholics, say they anticipate attending a family gathering at Christmastime.

This year, roughly eight-in-ten Americans (82%) say they intend to gather with family and friends on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day, down slightly since 2013 (86%). Large majorities in every religious group, ranging from 75% of religious “nones” to 89% of Catholics, say they anticipate attending a family gathering at Christmastime.

About half of American adults (51%) are planning to attend religious services on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. Among white evangelicals and white mainline Protestants, the shares who say they will attend religious services this Christmas are somewhat higher than in 2013. Among Catholics, by contrast, the share saying they will attend Christmas Mass has declined somewhat since 2013, from 76% to 68%.

Fully 84% of those who attend religious services on a weekly basis throughout the year say they will also go this Christmas. And most people who attend religious services occasionally – once or twice a month or a few times a year – also say they will go at Christmas (60%). Among those who seldom or never attend religious services, by contrast, very few (9%) say they will make an exception for Christmas.

Nearly two-thirds of Republicans and those who lean toward the GOP say they will attend church on Christmas (65%). Among Democrats, 45% plan on attending religious services this year.

Shrinking majority of public believes biblical Christmas story depicts actual events

Most Americans believe Jesus was born to a virgin, that he was visited by three wise men from the east, that his birth was announced to shepherds by an angel of the Lord, and that the baby Jesus was laid in a manger as an infant. But the share of Americans who believe that each of these four elements of the Christmas story reflects actual historical events is lower today than in 2014.

The declines in belief in the Christmas narrative are sharpest among religious “nones.” For instance, belief in the virgin birth has declined from 30% in 2014 to 17% today among religious “nones.” But even among some Christian groups, there are signs of growing doubts about the Christmas story as relayed in the Bible. The share of white mainline Protestants who believe in the virgin birth, for instance, has declined from 83% to 71%. And the share of Catholics who believe the birth of Jesus was announced by an angel of the Lord now stands at 82%, down from 90% in 2014.

Taken together, the data show that nine-in-ten white evangelical Protestants continue to believe in all four of these parts of the Christmas story, which is very similar to the share who said this in 2014. Among white mainline Protestants, by contrast, a shrinking majority believes in each of these four aspects of the Christmas narrative. (The change in the share of Catholics who believe in all four parts of the Christmas story is not statistically significant.)

Taken together, the data show that nine-in-ten white evangelical Protestants continue to believe in all four of these parts of the Christmas story, which is very similar to the share who said this in 2014. Among white mainline Protestants, by contrast, a shrinking majority believes in each of these four aspects of the Christmas narrative. (The change in the share of Catholics who believe in all four parts of the Christmas story is not statistically significant.)

Among religious “nones,” just 11% believe in all four of these parts of the Christmas story (down from 21%), while fully half believe in none of them (53%, up from 42%).

Three-quarters of Republicans believe in the virgin birth, the visit of the three wise men, the announcement of Jesus’ birth by an angel, and the laying of baby Jesus in a manger. By contrast, about half of Democrats (47%) believe in all four of these parts of the Christmas story.