In recent years, Europe has experienced a record influx of asylum seekers fleeing conflicts in Syria and other predominantly Muslim countries. This wave of Muslim migrants has prompted debate about immigration and security policies in numerous countries and has raised questions about the current and future number of Muslims in Europe.

In recent years, Europe has experienced a record influx of asylum seekers fleeing conflicts in Syria and other predominantly Muslim countries. This wave of Muslim migrants has prompted debate about immigration and security policies in numerous countries and has raised questions about the current and future number of Muslims in Europe.

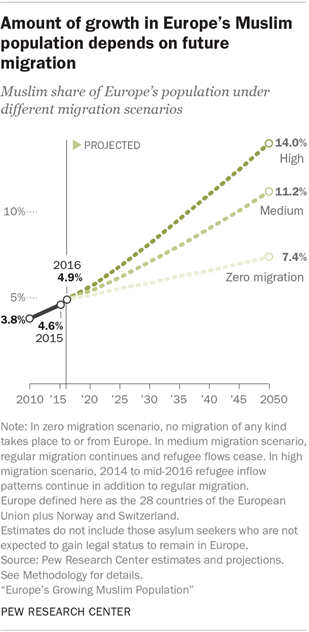

To see how the size of Europe’s Muslim population may change in the coming decades, Pew Research Center has modeled three scenarios that vary depending on future levels of migration. These are not efforts to predict what will happen in the future, but rather a set of projections about what could happen under different circumstances.

The baseline for all three scenarios is the Muslim population in Europe (defined here as the 28 countries presently in the European Union, plus Norway and Switzerland) as of mid-2016, estimated at 25.8 million (4.9% of the overall population) – up from 19.5 million (3.8%) in 2010.

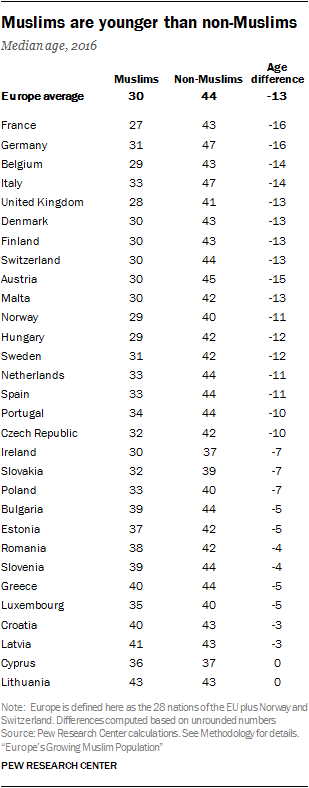

Even if all migration into Europe were to immediately and permanently stop – a “zero migration” scenario – the Muslim population of Europe still would be expected to rise from the current level of 4.9% to 7.4% by the year 2050. This is because Muslims are younger (by 13 years, on average) and have higher fertility (one child more per woman, on average) than other Europeans, mirroring a global pattern.

Even if all migration into Europe were to immediately and permanently stop – a “zero migration” scenario – the Muslim population of Europe still would be expected to rise from the current level of 4.9% to 7.4% by the year 2050. This is because Muslims are younger (by 13 years, on average) and have higher fertility (one child more per woman, on average) than other Europeans, mirroring a global pattern.

A second, “medium” migration scenario assumes that all refugee flows will stop as of mid-2016 but that recent levels of “regular” migration to Europe will continue (i.e., migration of those who come for reasons other than seeking asylum; see note on terms below). Under these conditions, Muslims could reach 11.2% of Europe’s population in 2050.

Finally, a “high” migration scenario projects the record flow of refugees into Europe between 2014 and 2016 to continue indefinitely into the future with the same religious composition (i.e., mostly made up of Muslims) in addition to the typical annual flow of regular migrants. In this scenario, Muslims could make up 14% of Europe’s population by 2050 – nearly triple the current share, but still considerably smaller than the populations of both Christians and people with no religion in Europe.

The refugee flows of the last few years, however, are extremely high compared with the historical average in recent decades, and already have begun to decline as the European Union and many of its member states have made policy changes aimed at limiting refugee flows (see sidebar).

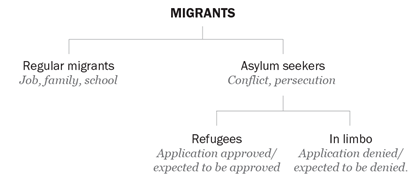

How key terms are used in this report: Regular migrants, asylum seekers and refugees

Migrants: This broad category includes all people moving across international borders to live in another country.

Regular migrants/other migrants: People who legally move to Europe for any reason other than seeking asylum – e.g., for economic, educational or family reasons.

Asylum seekers: Migrants who apply for refugee status upon entry to Europe. Asylum seekers whose requests for asylum are rejected can appeal the decision but cannot legally stay in Europe if the appeal is denied.

Refugees: Successful asylum seekers and those who are expected to receive legal status once their paperwork is processed. Estimates are based on recent rates of approval by European destination country for each origin country (among first-time applicants) and adjusted for withdrawals of asylum requests, which occur, for example, when asylum seekers move to another European country or outside of Europe.

In limbo: Asylum seekers whose application for asylum has been or is expected to be denied. Though this population may remain temporarily or illegally in Europe, these migrants are excluded from the population estimates and projections in this report.

Predicting future migration levels is impossible, because migration rates are connected not only to political and economic conditions outside of Europe, but also to the changing economic situation and government policies within Europe. Although none of these scenarios will play out exactly as projected, each provides a set of rough parameters from which to imagine other possible outcomes. For example, if regular migration continues at recent levels, and some asylum seekers also continue to arrive and receive refugee status – but not as many as during the historically exceptional surge of refugees from 2014 to 2016 – then the share of Muslims in Europe’s population as of 2050 would be expected to be somewhere between 11.2% and 14%.

While Europe’s Muslim population is expected to grow in all three scenarios – and more than double in the medium and high migration scenarios – Europe’s non-Muslims, on the other hand, are projected to decline in total number in each scenario. Migration, however, does mitigate this decline somewhat; nearly half of all recent migrants to Europe (47%) were not Muslim, with Christians making up the next-largest group.

While Europe’s Muslim population is expected to grow in all three scenarios – and more than double in the medium and high migration scenarios – Europe’s non-Muslims, on the other hand, are projected to decline in total number in each scenario. Migration, however, does mitigate this decline somewhat; nearly half of all recent migrants to Europe (47%) were not Muslim, with Christians making up the next-largest group.

Taken as a whole, Europe’s population (including both Muslims and non-Muslims) would be expected to decline considerably (from about 521 million to an estimated 482 million) without any future migration. In the medium migration scenario, it would remain roughly stable, while in the high migration scenario it would be projected to grow modestly.

The impact of these scenarios is uneven across different European countries (see maps below); due in large part to government policies, some countries are much more affected by migration than others.

Countries that have received relatively large numbers of Muslim refugees in recent years are projected to experience the biggest changes in the high migration scenario – the only one that projects these heavy refugee flows to continue into the future. For instance, Germany’s population (6% Muslim in 2016) would be projected to be about 20% Muslim by 2050 in the high scenario – a reflection of the fact that Germany has accepted many Muslim refugees in recent years – compared with 11% in the medium scenario and 9% in the zero migration scenario.

Countries that have received relatively large numbers of Muslim refugees in recent years are projected to experience the biggest changes in the high migration scenario – the only one that projects these heavy refugee flows to continue into the future. For instance, Germany’s population (6% Muslim in 2016) would be projected to be about 20% Muslim by 2050 in the high scenario – a reflection of the fact that Germany has accepted many Muslim refugees in recent years – compared with 11% in the medium scenario and 9% in the zero migration scenario.

Sweden, which also has accepted a relatively high number of refugees, would experience even greater effects if the migration levels from 2014 to mid-2016 were to continue indefinitely: Sweden’s population (8% Muslim in 2016) could grow to 31% Muslim in the high scenario by 2050, compared with 21% in the medium scenario and 11% with no further Muslim migration.

By contrast, the countries projected to experience the biggest changes in the medium scenario (such as the UK) tend to have been destinations for the highest numbers of regular Muslim migrants. This scenario only models regular migration.

And countries with Muslim populations that are especially young, or have a relatively large number of children, would see the most significant change in the zero migration scenario; these include France, Italy and Belgium.

And countries with Muslim populations that are especially young, or have a relatively large number of children, would see the most significant change in the zero migration scenario; these include France, Italy and Belgium.

Some countries would experience little change in any of the scenarios, typically because they have few Muslims to begin with or low levels of immigration (or both).

The starting point for all these scenarios is Europe’s population as of mid-2016. Coming up with an exact count of Muslims currently in Europe, however, is not a simple task. The 2016 estimates are based on Pew Research Center analysis and projections of the best available census and survey data in each country combined with data on immigration from Eurostat and other sources. While Muslim identity is often measured directly, in some cases it must be estimated indirectly based upon the national origins of migrants (see Methodology for details).

One source of uncertainty is the status of asylum seekers who are not granted refugee status. An estimated 3.7 million Muslims migrated to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016, including approximately 2.5 million regular migrants entering legally as workers, students, etc., as well as 1.3 million Muslims who have or are expected to be granted refugee status (including an estimated 980,000 Muslim refugees who arrived between 2014 and mid-2016).

One source of uncertainty is the status of asylum seekers who are not granted refugee status. An estimated 3.7 million Muslims migrated to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016, including approximately 2.5 million regular migrants entering legally as workers, students, etc., as well as 1.3 million Muslims who have or are expected to be granted refugee status (including an estimated 980,000 Muslim refugees who arrived between 2014 and mid-2016).

Based on recent rates of approval of asylum applications, Pew Research Center estimates that nearly a million (970,000) additional Muslim asylum seekers who came to Europe in recent years will not have their applications for asylum accepted, based on past rates of approval on a country-by-country basis. These estimates also take into account expected rates of withdrawals of requests for refugee status (see Methodology for details).

Where these asylum seekers “in limbo” ultimately will go is unclear: Some may leave Europe voluntarily or be deported, while others will remain at least temporarily while they appeal their asylum rejection. Some also could try to stay in Europe illegally.

For the future population projections presented in this report, it is assumed that only Muslim migrants who already have – or are expected to gain – legal status in Europe will remain for the long term, providing a baseline of 25.8 million Muslims as of 2016 (4.9% of Europe’s population). However, if all of the approximately 1 million Muslims who are currently in legal limbo in Europe were to remain in Europe – which seems unlikely – the 2016 baseline could rise as high as 26.8 million, with ripple effects across all three scenarios.

These are a few of the key findings from a new Pew Research Center demographic analysis – part of a broader effort to project the population growth of religious groups around the world. This report, which focuses on Muslims in Europe due to the rapid changes brought on by the recent influx of refugees, provides the first estimates of the growing size of the Muslim population in Europe following the wave of refugees between 2014 and mid-2016. It uses the best available data combined with estimation and projection methods developed in prior Pew Research Center demographic studies. The projections take into account the current size of both the Muslim and non-Muslim populations in Europe, as well as international migration, age and sex composition, fertility and mortality rates, and patterns in conversion. (See Methodology for details.)

Europe’s Muslim population is diverse. It encompasses Muslims born in Europe and in a wide variety of non-European countries. It includes Sunnis, Shiites, and Sufis. Levels of religious commitment and belief vary among Europe’s Muslim populations. Some of the Muslims enumerated in this report would not describe Muslim identity as salient in their daily lives. For others, Muslim identity profoundly shapes their daily lives. However, quantifying religious devotion and categories of Muslim identity is outside the scope of this report.

Between mid-2010 and mid-2016, the number of Muslims in Europe grew considerably through natural increase alone – that is, estimated births outnumbered deaths among Muslims by more than 2.9 million over that period. But most of the Muslim population growth in Europe during the period (about 60%) was due to migration: The Muslim population grew by an estimated 3.5 million from net migration (i.e., the number of Muslims who arrived minus the number who left, including both regular migrants and refugees). Over the same period, there was a relatively small loss in the Muslim population due to religious switching – an estimated 160,000 more people switched their religious identity from Muslim to another religion (or to no religion) than switched into Islam from some other religion or no religion – although this had a modest impact compared with births, deaths and migration.1

Between mid-2010 and mid-2016, the number of Muslims in Europe grew considerably through natural increase alone – that is, estimated births outnumbered deaths among Muslims by more than 2.9 million over that period. But most of the Muslim population growth in Europe during the period (about 60%) was due to migration: The Muslim population grew by an estimated 3.5 million from net migration (i.e., the number of Muslims who arrived minus the number who left, including both regular migrants and refugees). Over the same period, there was a relatively small loss in the Muslim population due to religious switching – an estimated 160,000 more people switched their religious identity from Muslim to another religion (or to no religion) than switched into Islam from some other religion or no religion – although this had a modest impact compared with births, deaths and migration.1

By comparison, the non-Muslim population in Europe declined slightly between 2010 and 2016. A natural decrease of about 1.7 million people in the non-Muslim European population modestly outnumbered the net increase of non-Muslim migrants and a modest net change due to religious switching.

The rest of the report looks at these findings in greater detail. The first section examines the number of migrants to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016, including patterns by religion and refugee status. The next section details the top origin and destination countries for recent migrants to Europe, including in each case the estimated percentage of Muslims. One sidebar looks at European public opinion toward the surge in refugees from countries like Iraq and Syria; another summarizes trends in government policies toward refugees and migration in individual countries and the EU as a whole. The following section examines more deeply the three projection scenarios on a country-by-country basis. Finally, the last two sections reveal data on two other key demographic factors that affect population growth: fertility and age structure.

This report was produced by Pew Research Center as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.

Surge in refugees – most of them Muslim – between 2014 and mid-2016

Overall, regardless of religion or immigration status, there were an estimated 7 million migrants to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (not including 1.7 million asylum seekers who are not expected to have their applications for asylum approved).

Overall, regardless of religion or immigration status, there were an estimated 7 million migrants to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (not including 1.7 million asylum seekers who are not expected to have their applications for asylum approved).

Historically, a relatively small share of migrants to Europe are refugees from violence or persecution in their home countries.2 This continued to be the case from mid-2010 to mid-2016 – roughly three-quarters of migrants to Europe in this period (5.4 million) were regular migrants (i.e., not refugees).

But the number of refugees has surged since 2014. During the three-and-a-half-year period from mid-2010 to the end of 2013, about 400,000 refugees (an average of 110,000 per year) arrived in Europe. Between the beginning of 2014 and mid-2016 – a stretch of only two and a half years – roughly three times as many refugees (1.2 million, or about 490,000 annually) came to Europe, as conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan continued or intensified. (These figures do not include an additional 970,000 Muslim asylum seekers and 680,000 non-Muslim asylum seekers who arrived between mid-2010 and mid-2016 but are not projected to receive legal status in Europe.)

But the number of refugees has surged since 2014. During the three-and-a-half-year period from mid-2010 to the end of 2013, about 400,000 refugees (an average of 110,000 per year) arrived in Europe. Between the beginning of 2014 and mid-2016 – a stretch of only two and a half years – roughly three times as many refugees (1.2 million, or about 490,000 annually) came to Europe, as conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan continued or intensified. (These figures do not include an additional 970,000 Muslim asylum seekers and 680,000 non-Muslim asylum seekers who arrived between mid-2010 and mid-2016 but are not projected to receive legal status in Europe.)

Of these roughly 1.6 million people who received refugee status in Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (or are expected to have their applications approved in the future), more than three-quarters (78%, or 1.3 million) were estimated to be Muslims.3 By comparison, a smaller percentage of regular migrants to Europe in this period (46%) were Muslims, although this still greatly exceeds the share of Europe’s overall population that is Muslim and thus contributes to Europe’s growing Muslim population. In fact, about two-thirds of all Muslims who arrived in Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 were regular migrants and not refugees.

Of these roughly 1.6 million people who received refugee status in Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (or are expected to have their applications approved in the future), more than three-quarters (78%, or 1.3 million) were estimated to be Muslims.3 By comparison, a smaller percentage of regular migrants to Europe in this period (46%) were Muslims, although this still greatly exceeds the share of Europe’s overall population that is Muslim and thus contributes to Europe’s growing Muslim population. In fact, about two-thirds of all Muslims who arrived in Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 were regular migrants and not refugees.

Altogether, a slim majority of all migrants to Europe – both refugees and regular migrants – between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (an estimated 53%) were Muslim. In total number, roughly 3.7 million Muslims and 3.3 million non-Muslims arrived in Europe during this period.

Non-Muslim migrants to Europe overall between mid-2010 and mid-2016 were mostly made up of Christians (an estimated 1.9 million), people with no religious affiliation (410,000), Buddhists (390,000) and Hindus (350,000). Christians made up 30% of regular migrants overall (1.6 million regular Christian migrants; 55% of all non-Muslim regular migrants) and 16% of all refugees (250,000 Christian refugees; 71% of all non-Muslim refugees).

Syria is top origin country not only for refugees but also for all Muslim migrants to Europe

Considering the total influx of refugees and regular migrants together, more migrants to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 came from Syria than any other country. Of the 710,000 Syrian migrants to Europe during this period, more than nine-in-ten (94%, or 670,000) came seeking refuge from the Syrian civil war, violence perpetrated by the Islamic State or some other strife.

Considering the total influx of refugees and regular migrants together, more migrants to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 came from Syria than any other country. Of the 710,000 Syrian migrants to Europe during this period, more than nine-in-ten (94%, or 670,000) came seeking refuge from the Syrian civil war, violence perpetrated by the Islamic State or some other strife.

An estimated nine-in-ten Syrian migrants (91%) were Muslims. In this case and many others, migrants’ religious composition is assumed to match the religious composition of their origin country. In some other cases, data are available for migrants from a particular country to a destination country; for example, there is a higher share of Christians among Egyptian migrants to Austria than there is among those living in Egypt. When available, this type of data is used to estimate the religious composition of new migrants. (For more details, see the Methodology.)

After Syria, the largest sources of recent refugees to Europe are Afghanistan (180,000) and Iraq (150,000). Again, in both cases, nearly all of the migrants from these countries were refugees from conflict, and overwhelming majorities from both places were Muslims.

Several other countries, however, were the origin of more overall migrants to Europe. India, for example, was the second-biggest source of migrants to Europe (480,000) between mid-2010 and mid-2016; very few of these migrants came as refugees, and only an estimated 15% were Muslims.

The top countries of origin of migrants in legal limbo are not necessarily the top countries of origin among legally accepted refugees. For example, relatively few Syrians are in legal limbo, while Albania, where fewer asylum seekers come from, is the origin of a large number of rejected applicants. Afghanistan, meanwhile, is both a major source of legally accepted refugees and also a major country of origin of those in legal limbo.

Since the primary criterion for asylum decisions is the safety of the origin country, particularly dangerous countries, such as Syria, have much higher acceptance rates than others. For more information on the countries of origin of those in legal limbo see Pew Research Center’s 2017 report, “Still in Limbo: About a Million Asylum Seekers Await Word on Whether They Can Call Europe Home.”

Syria also was by far the single biggest source of Muslim migrants to Europe overall in recent years. But Morocco, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Iran also sent considerable numbers of Muslim migrants to Europe between mid-2010 and mid-2016 – more than 1 million combined – and the vast majority of Muslims from these countries came to Europe as regular migrants and not as refugees.

Germany is top destination for Muslim refugees; UK is leading destination for regular Muslim migrants

Germany was the destination for an estimated 670,000 refugees between mid-2010 and mid-2016 – more than three times as many as the country with the next-largest number, Sweden (200,000). A similar number of regular migrants from outside Europe also arrived in Germany in recent years (680,000). But religiously, refugees and other migrants to Germany look very different; an estimated 86% of refugees accepted by Germany were Muslims, compared with just 40% of regular migrants to Germany.

Germany was the destination for an estimated 670,000 refugees between mid-2010 and mid-2016 – more than three times as many as the country with the next-largest number, Sweden (200,000). A similar number of regular migrants from outside Europe also arrived in Germany in recent years (680,000). But religiously, refugees and other migrants to Germany look very different; an estimated 86% of refugees accepted by Germany were Muslims, compared with just 40% of regular migrants to Germany.

Germany has the largest population and economy in Europe, is centrally located on the continent and has policies favorable toward asylum seekers (for more on EU policies toward refugees, see this sidebar). The UK, however, actually was the destination for a larger number of migrants from outside Europe overall between mid-2010 and mid-2016 (1.6 million). The UK voted in a 2016 referendum to leave the EU, which may impact immigration patterns in the future, but it is still counted as part of Europe in this report.

Relatively few recent immigrants to the UK (60,000) were refugees, but more than 1.5 million regular migrants arrived there in recent years. Overall, an estimated 43% of all migrants to the UK between mid-2010 and mid-2016 were Muslims.

Combining Muslim refugees and Muslim regular migrants, Germany was the destination for more Muslim migrants overall than the UK (850,000 vs. 690,000).

France also received more than half a million Muslim migrants – predominantly regular migrants – between mid-2010 and mid-2016, while 400,000 Muslims arrived in Italy. The two countries accepted a combined total of 210,000 refugees (130,000 by Italy and 80,000 by France), most of whom were Muslims.

Sweden received even more refugees than the UK, Italy and France, all of which have much larger populations. A large majority of these 200,000 refugees (an estimated 77%) were Muslims; Sweden also received 250,000 regular migrants, most of whom were Muslims (58%). Overall, 300,000 Muslim migrants – 160,000 of whom were refugees – arrived in Sweden in recent years. Only Germany, the UK, France and Italy received more Muslim migrants to Europe overall since mid-2010. But because Sweden is home to fewer than 10 million people, these arrivals have a bigger impact on Sweden’s overall religious composition than does Muslim migration to larger countries in Western Europe.

These estimates do not include migration from one EU country to another. Some countries, particularly Germany, received a large number of regular migrants from within the EU. In fact, with about 800,000 newcomers from other EU countries, Germany received more intra-EU migrants than regular migrants from outside the EU. Intra-EU migrants tend to have a similar religious composition to Europeans overall.

The number of Muslim asylum seekers in legal limbo – i.e., those who already have had or are expected to have their applications for asylum rejected – varies substantially from country to country, largely because of differences in policies on asylum, variation in the number of applications received and differing origins of those migrants. Germany, for example, has a high number of Muslim migrants in legal limbo despite a relatively low rejection rate – mainly because it has received such a large number of applications for asylum. Germany received about 900,000 applications for asylum from Muslims between mid-2010 and mid-2016, and is projected to ultimately accept 580,000 and reject roughly 320,000 – or slightly more than one-third (excluding applications that were withdrawn).

This rejection rate is similar to Sweden’s; Sweden ultimately is expected to reject an estimated 90,000 out of roughly 240,000 Muslim applications (again, excluding withdrawals). France, meanwhile, is projected to reject three-quarters of applications from Muslims, leaving an “in limbo” population of 140,000 (out of 190,000 Muslim applications). Italy is expected to reject about half of Muslim applicants (90,000 out of 190,000 applications), and the UK is projected to reject 60,000 out of 100,000.

Data for the 2010 to 2013 period are based on application decision rates. But due to the combination of still-unresolved applications and lack of comprehensive data on recent decisions when this analysis took place, rejection patterns for the 2014 to mid-2016 period are estimated based on 2010 to 2013 rates of rejection for each origin and destination country pair (for details, see Methodology). There is no religious preference inherent to the asylum regulations in Europe. However, if religious persecution is a reason for seeking asylum, that context (as opposed to religious affiliation in and of itself) can be considered in the decision process. Religion is estimated in this report based on available information about countries of origin and migration flow patterns by religion – application decisions are not reported by religious group.

Iraqi and Syrian refugees perceived as less of a threat in countries where more of them have sought asylum

For instance, Germany has been the primary destination country for asylum seekers from the Middle East, receiving 457,000 applications from Iraqis and Syrians between mid-2010 and mid-2016. Yet the share of people in Germany who say “large numbers of refugees from countries such as Iraq and Syria” pose a “major threat” is among the lowest of all European countries surveyed (28%).

For instance, Germany has been the primary destination country for asylum seekers from the Middle East, receiving 457,000 applications from Iraqis and Syrians between mid-2010 and mid-2016. Yet the share of people in Germany who say “large numbers of refugees from countries such as Iraq and Syria” pose a “major threat” is among the lowest of all European countries surveyed (28%).

Similarly, in Sweden, just 22% of the public says these refugees constitute a “major threat.” Iraqi and Syrian asylum seekers make up an even greater share of Sweden’s population than Germany’s; there are 139 asylum seekers from these countries for every 10,000 Swedes.

By contrast, majorities of the public in Greece (67%), Italy (65%) and Poland (60%) say large numbers of refugees from countries such as Iraq and Syria represent a “major threat,” even though there are relatively few such asylum seekers in these countries.4 Indeed, there are fewer than 10,000 people from Iraq and Syria seeking asylum in Italy and Poland combined, representing one or fewer per 10,000 residents in each country.

This pattern is not universal. Hungary received 85,000 applications for asylum from Iraqi and Syrian refugees between mid-2010 and mid-2016 – among the highest figures in Europe – and most Hungarians (66%) see this surge of refugees as a major threat. Hungary’s government decided to close its border with Croatia in October 2015, erecting a fence to keep migrants out. Tens of thousands of applications for asylum in Hungary have been withdrawn since 2015. (For more on government policies toward migration, see this sidebar.)

Concerns about refugees from Iraq and Syria, most of whom are Muslims, are tied to negative views about Muslims in general. In all 10 EU countries that were part of a Pew Research Center survey in 2016, people who have an unfavorable view of Muslims are especially likely to see a threat associated with Iraqi and Syrian refugees. In the United Kingdom, for example, 80% of those who have an unfavorable opinion of Muslims say large numbers of refugees from countries such as Iraq and Syria represent a major threat. Among British adults who view Muslims favorably, just 40% see the refugees as a major threat.

EU restrictions on migration tightening after surge

Changing government policies in European countries can have a major impact on migration flows. In recent years, several European countries – and the European Union itself, acting on behalf of its member states – have adopted policies that have generally moved to tighten Europe’s borders and to limit flows of migrants.

In 2016, the EU signed a deal with Turkey, a frequent stop for migrants coming from Syria. Under the terms of the deal, Greece, which shares a border with Turkey, can return to Turkey all new “irregular” or illegal migrants. In exchange, EU member states pledged to resettle more Syrian refugees living in Turkey and to increase financial aid for those remaining there. By 2017, the agreement had reduced by 97% the number of migrants coming from Turkey into Greece, according to the EU migration commissioner.

Another common path for large numbers of migrants to Europe is from sub-Saharan Africa to Italy, where they primarily arrive by sea from the Libyan coast. To try to stem the tide, Italy has worked with the Libyan coast guard to develop techniques to stop boats carrying the migrants, among other policies and tactics.

In addition, even Germany – the destination of more recent asylum seekers than any other European country — has deported some migrants, including to Afghanistan, and moved toward tougher border controls. German Chancellor Angela Merkel, following a September 2017 election that saw the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party gain a presence in parliament for the first time, agreed to a limit of 200,000 asylum seekers per year.

Sweden and Austria also have accepted high numbers of refugees, especially relative to their small populations. But in November 2015, leaders announced a tightening of Sweden’s refugee policy, requiring identity checks to be imposed on all forms of transportation, and limiting family reunification with refugees. And in an October 2017 election, Austrian voters favored parties that had campaigned on taking a harder line on immigration.

Immigration – and not just by refugees – has been a major campaign issue in several countries, and it was one of the key factors in the Brexit debate over whether the UK, the destination of more regular migrants than any other European country in recent years, should remain in the European Union. In the aftermath of the 2016 referendum in which British voters opted to leave the EU, UK government officials have vowed to remove the country from the freedom-of-movement policy, which allows EU citizens to move to and work in EU member states without having to apply for visas, in March 2019.

How Europe’s Muslim population is projected to change in future decades

Pew Research Center’s three scenarios projecting the future size of the Muslim population in Europe reflect uncertainty about future migration flows due to political and social conditions outside of Europe, as well as shifting immigration policies in the region.

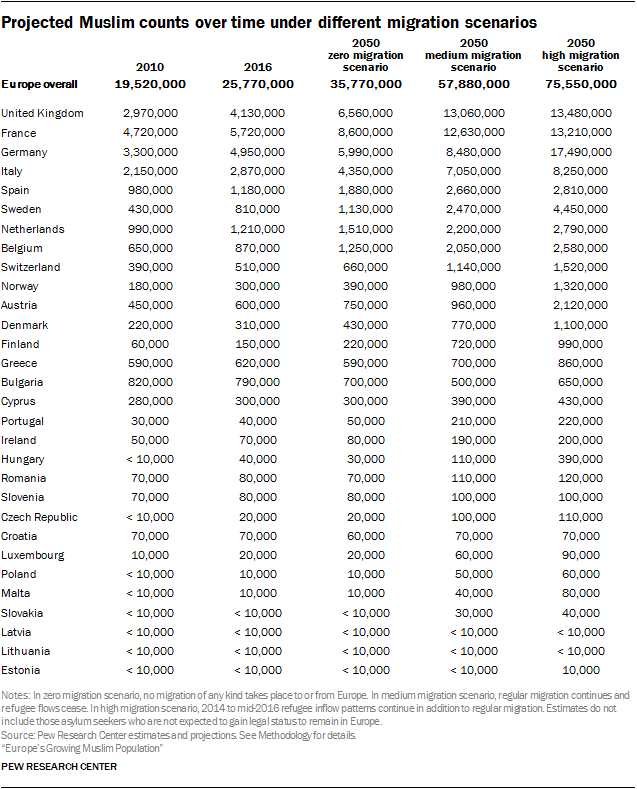

These projections start from an estimated baseline of 26 million Muslims in Europe as of 2016, which excludes asylum seekers who are not expected to gain legal status. Even with no future migration, Europe’s Muslim population is projected to increase by 10 million by 2050 based on fertility and age patterns (see here). If past levels of regular migration continue in the future – but with no more asylum seekers — the Muslim population in Europe would increase to nearly 58 million by midcentury (the medium scenario). And if the heavy refugee flows seen in recent years were to continue in the future on top of regular migration (the high migration scenario), there would be more than 75 million Muslims in Europe as of 2050.

In all three scenarios, the non-Muslim population in Europe is projected to shrink in total number between now and 2050.

As of 2016, France and Germany have the highest numbers of Muslims in Europe. But in the medium migration scenario, the United Kingdom would surpass them, with a projected 13 million Muslims in 2050 (compared with a projected 12.6 million in France and 8.5 million in Germany). This is because the UK was the top destination country for regular Muslim migrants (as opposed to refugees) between mid-2010 and mid-2016, and the medium scenario assumes that only regular immigration will continue.

Alternatively, in the high migration scenario, Germany would have by far the highest number of Muslims in 2050 – 17.5 million. This projection reflects Germany’s acceptance of a large number of Muslim refugees in recent years. The high scenario assumes that these refugee flows will continue in the coming decades, not only at the same volume but also with the same religious composition (i.e., that many refugees will continue to come from predominantly Muslim countries). Compared with the UK and France, Germany has received fewer regular Muslim migrants in recent years.

Other, smaller European countries also are expected to experience significant growth in their Muslim populations if regular migration or an influx of refugees continues (or both). For instance, in Sweden, the number of Muslims would climb threefold from fewer than a million (810,000) in 2016 to nearly 2.5 million in 2050 in the medium scenario, and fivefold to almost 4.5 million in the high scenario.

But some countries – even some large ones, like Poland – had very few Muslims in 2016 and are projected to continue to have very few Muslims in 2050 in all three scenarios. Poland’s Muslim population was roughly 10,000 in 2016 and would only rise to 50,000 in the medium scenario and 60,000 in the high scenario.

These growing numbers of Muslims in Europe, combined with the projected shrinkage of the non-Muslim population, are expected to result in a rising share of Muslims in Europe’s overall population in all scenarios.

These growing numbers of Muslims in Europe, combined with the projected shrinkage of the non-Muslim population, are expected to result in a rising share of Muslims in Europe’s overall population in all scenarios.

Even if every EU country plus Norway and Switzerland immediately closed its borders to any further migration, the Muslim share of the population in these 30 countries would be expected to rise from 4.9% in 2016 to 7.4% in 2050 simply due to prevailing demographic trends. In the medium migration scenario, with projected future regular migration but no refugees, the Muslim share of Europe would rise to 11.2% by midcentury. And if high refugee flows were to continue in future decades, Europe would be 14% Muslim in 2050 – a considerable increase, although still a relative minority in a Christian-majority region.

Cyprus currently has the highest share of Muslims in the EU (25.4%), due largely to the historical presence of predominantly Muslim Turkish Cypriots in the northern part of the island. Migration is not projected to dramatically change the Muslim share of the population in Cyprus in future scenarios.

In both the zero and medium migration scenarios, Cyprus would maintain the largest Muslim share in Europe in 2050. But in the high migration scenario, Sweden – which was among the countries to accept a large number of refugees during the recent surge – is projected to surpass even Cyprus. In this scenario, roughly three-in-ten Swedes (30.6%) would be Muslim at midcentury.

Even in the medium scenario, without any future refugee flows, Sweden would be expected to have the second-largest Muslim share (20.5%) as of 2050. If migration were to stop altogether, a much smaller percentage of Swedes (11.1%) would be Muslim in 2050.

Migration also drives the projected increase in the Muslim shares of France, the UK and several other countries. Both France and the UK are expected to be roughly 17% Muslim by 2050 in the medium scenario, several percentage points higher than they would be if all future migration were to stop. Because both countries have accepted many more Muslim regular migrants than Muslim refugees, France and the UK do not vary as greatly between the medium scenario and the high scenario.

Germany, on the other hand, sees a dramatic difference in its projected Muslim share depending on future refugee flows. The share of Muslims in Germany (6.1% in 2016) would increase to 10.8% in 2050 under the medium scenario, in which regular migration continues at its recent pace and refugee flows stop entirely. But it would rise far more dramatically, to 19.7%, in the high scenario, if the recent volume of refugee flows continues as well. There is a similar pattern in Austria (6.9% Muslim in 2016, 10.6% in 2050 in the medium scenario and 19.9% in 2050 in the high scenario).

Another way to look at these shifts is by examining the extent of the projected change in the share of each country that is Muslim in different scenarios.

Another way to look at these shifts is by examining the extent of the projected change in the share of each country that is Muslim in different scenarios.

From now until midcentury, some countries in Europe could see their Muslim populations rise significantly in the medium and high scenarios. For example, the Muslim shares of both Sweden and the UK would rise by more than 10 percentage points in the medium scenario, while several other countries would experience a similar increase in the high scenario. The biggest increase for a country in any scenario would be Sweden in the high scenario – an increase of 22.4 percentage points, with the percentage of Muslims in the Swedish population rising to 30.6%.

Other countries would see only marginal increases under these scenarios. For example, Greece’s Muslim population is expected to rise by just 2.4 percentage points in the medium scenario. And hardly any change is projected in any scenario in several Central and Eastern European countries, including Poland, Latvia and Lithuania.

In Europe overall, even if all Muslim migration into Europe were to immediately and permanently stop – a zero migration scenario – the overall Muslim population of Europe would be expected to rise by 2.5 percentage points, from the current level of 4.9% to 7.4% by 2050. This is because Muslims in Europe are considerably younger and have a higher fertility rate than other Europeans. Without any future migrants, these prevailing demographic trends would lead to projected rises of at least 3 percentage points in the Muslim shares of France, Belgium, Italy and the UK.

Muslims have an average of one more child per woman than other Europeans

Migration aside, fertility rates are among the other dynamics driving Europe’s growing Muslim population. Europe’s Muslims have more children than members of other religious groups (or people with no religion) in the region. (New Muslim migrants to Europe are assumed to have fertility rates that match those of Muslims in their destination countries; for more details, see Methodology.)

Migration aside, fertility rates are among the other dynamics driving Europe’s growing Muslim population. Europe’s Muslims have more children than members of other religious groups (or people with no religion) in the region. (New Muslim migrants to Europe are assumed to have fertility rates that match those of Muslims in their destination countries; for more details, see Methodology.)

Not all children born to Muslim women will ultimately identify as Muslims, but children are generally more likely to adopt their parents’ religious identity than any other.5

Taken as a whole, non-Muslim European women are projected to have a total fertility rate of 1.6 children, on average, during the 2015-2020 period, compared with 2.6 children per Muslim woman in the region. This difference of one child per woman is particularly significant given that fertility among European Muslims exceeds replacement level (i.e., the rate of births needed to sustain the size of a population) while non-Muslims are not having enough children to keep their population steady.

The difference between Muslim women and others varies considerably from one European country to another. In some countries, the disparity is large. The current estimated fertility rate for Muslim women in Finland, for example, is 3.1 children per woman, compared with 1.7 for non-Muslim Finns.6

Among Western European countries with the largest Muslim populations, Germany’s Muslim women have relatively low fertility, at just 1.9 children per woman (compared with 1.4 for non-Muslim Germans). Muslims in the UK and France, meanwhile, average 2.9 children – a full child more per woman than non-Muslims. This is one reason the German Muslim population – both in total number and as a share of the overall population – is not projected to keep pace with the British and French Muslim populations, except in the high scenario (which includes large future refugee flows).

Among Western European countries with the largest Muslim populations, Germany’s Muslim women have relatively low fertility, at just 1.9 children per woman (compared with 1.4 for non-Muslim Germans). Muslims in the UK and France, meanwhile, average 2.9 children – a full child more per woman than non-Muslims. This is one reason the German Muslim population – both in total number and as a share of the overall population – is not projected to keep pace with the British and French Muslim populations, except in the high scenario (which includes large future refugee flows).

In some countries, including Bulgaria and Greece, there is little difference in fertility rates between Muslims and non-Muslims.

Over time, Muslim fertility rates are projected to decline, narrowing the gap with the non-Muslim population from a full child per woman today to 0.7 children between 2045 and 2050. This is because the fertility rates of second- and third-generation immigrants generally become similar to the overall rates in their adopted countries.

The low fertility rate in Europe among non-Muslims is largely responsible for the projected decline in the region’s total population without future migration.

Young Muslim population in Europe contributes to growth

The age distribution of a religious group also is an important determinant of demographic growth.

The age distribution of a religious group also is an important determinant of demographic growth.

European Muslims are concentrated in young age groups – the share of Muslims younger than 15 (27%) is nearly double the share of non-Muslims who are children (15%). And while one-in-ten non-Muslim Europeans are ages 75 and older, this is true of only 1% of Muslims in Europe.

European Muslims are concentrated in young age groups – the share of Muslims younger than 15 (27%) is nearly double the share of non-Muslims who are children (15%). And while one-in-ten non-Muslim Europeans are ages 75 and older, this is true of only 1% of Muslims in Europe.

As of 2016, there is a 13-year difference between the median age of Muslims in Europe (30.4 years of age) and non-Muslim Europeans (43.8). Because a larger share of Muslims relative to the general population are in their child-bearing years, their population would grow faster, even if Muslims and non-Muslims had the same fertility rates.

As of 2016, France and Germany have the greatest age differences in Europe between Muslims and non-Muslims. The median age of Muslims in France is just 27, compared with 43 for non-Muslims. Germany has an equally large gap (31 for Muslims, 47 for non-Muslims).