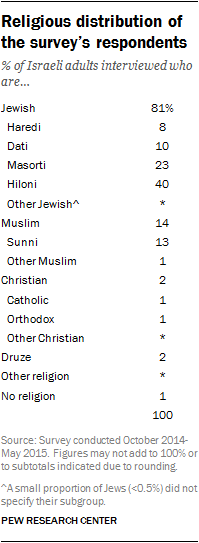

The vast majority of Israeli respondents in this survey identify as Jews (81%), including 40% who identify as Hiloni, 23% as Masorti, 10% as Dati and 8% as Haredi.

The vast majority of Israeli respondents in this survey identify as Jews (81%), including 40% who identify as Hiloni, 23% as Masorti, 10% as Dati and 8% as Haredi.

The sample also includes Muslims (14%), Christians (2%) and Druze (2%). Few Israelis analyzed in this study say they have no religion (1%).

After accounting for oversamples of Christians, Druze, Jews who identify as Haredi and Jews who live in the West Bank, the religious distribution of the survey’s respondents closely resembles the religious distribution of the adult population published in the 2014 Statistical Abstract by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics.

Readers should bear in mind that because of relatively high birthrates among Muslims who live in Israel, the proportion of Jews is slightly higher among adults than it is among children. The reverse is true for Muslims, who make up a higher share of children than they do of adults in Israel.

Slight discrepancies between survey proportions and census proportions also may result from the definition of religious groups used in the survey. For example, this report treats a small number of Israelis as Jewish even though they describe themselves, religiously, as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular because they have at least one Jewish parent or were raised Jewish and consider themselves Jewish aside from religion. This parallels the definition of “who is a Jew” that was used in Pew Research Center’s 2013 survey of Jews in the United States. (See the sidebar on “How religious groups are defined” in the Overview of this report.)

Roughly half of Jews identify as Hiloni (secular)

Roughly one-in-five Israeli Jews (22%) identify with groups that are commonly considered Orthodox: Haredim (9%) and Datiim (13%).

Roughly one-in-five Israeli Jews (22%) identify with groups that are commonly considered Orthodox: Haredim (9%) and Datiim (13%).

Fully three-quarters of Israeli Jews (78%) identify as Masortim (29%) and Hilonim (49%).

Among Jews, these four groups display a broad spectrum of religious observance. Haredim and Hilonim form the bookends of the spectrum: Those who identify themselves as Haredim show the highest levels of religious observance, while Hilonim are, on the whole, the least observant.

Datiim also adhere closely to Jewish law, although on several standard measures of religious observance and practice, they are somewhat less religiously committed than Haredim. Masortim often display moderate levels of religious belief and practice. (See Chapter 4: Religious Commitment, and Chapter 5: Jewish Beliefs and Practices.)

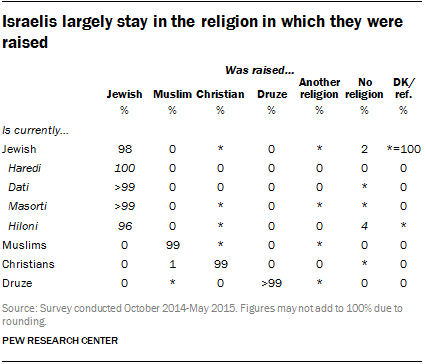

Virtually no conversion across religions in Israel

Nearly universally, adults in Israel who identify as Jews were raised Jewish. Fully 98% of Israelis who currently identify as Jewish were raised Jewish.

Nearly universally, adults in Israel who identify as Jews were raised Jewish. Fully 98% of Israelis who currently identify as Jewish were raised Jewish.

Religious conversion also is uncommon among Israeli Muslims, Christians and Druze. Nearly all respondents who currently identify as Muslim, Christian or Druze say they were raised within those religious traditions.

Net loss for Datiim through switching to other Jewish subgroups

The survey shows a slight net loss for Datiim between the share who were raised Dati and the share who currently identify as Dati. Fully 19% of Jews were raised Dati, while 13% currently identify as Dati – a loss of 6 percentage points.

The survey shows a slight net loss for Datiim between the share who were raised Dati and the share who currently identify as Dati. Fully 19% of Jews were raised Dati, while 13% currently identify as Dati – a loss of 6 percentage points.

But among other Jewish subgroups, there are no significant differences between the shares who were raised Haredi, Masorti or Hiloni and the shares who currently identify with these groups. For example, 8% of adults were raised Haredim, while about as many (9%) currently identify as Haredim.

But among other Jewish subgroups, there are no significant differences between the shares who were raised Haredi, Masorti or Hiloni and the shares who currently identify with these groups. For example, 8% of adults were raised Haredim, while about as many (9%) currently identify as Haredim.

This overall picture of stability masks substantial movement among Jewish subgroups. For example, while the proportion of Jewish adults raised Masorti is roughly the same as the proportion that is currently Masorti, 9% of Jewish adults say they were raised Masorti and are no longer in the group, while 10% of adults were raised in another group and now identify as Masortim.

Similarly, while the proportion of Hilonim has remained relatively stable during survey respondents’ lifetimes, 4% of Israeli Jewish adults were raised as Hilonim and no longer identify as such, while twice as many (8%) now identify as Hilonim after having been raised in a different subgroup.

About one-in-ten Jewish adults (9%) were raised Datiim and are no longer Datiim, while approximately 2% now consider themselves Datiim after being raised in another group.

Compared with the other three groups, there has been relatively little switching out of the Haredi community.

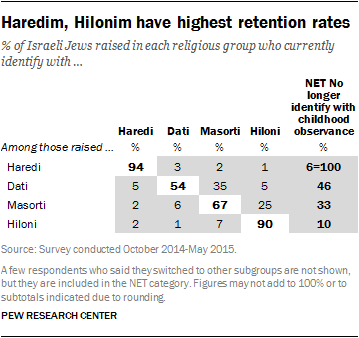

Jews raised as Haredi or Hiloni usually stay

Overall, the two poles of Israeli Judaism – Hilonim and Haredim – experience the highest retention rates. The vast majority of those raised Haredim are still Haredim (94%), and nine-in-ten Jews raised Hilonim are still Hilonim.

Overall, the two poles of Israeli Judaism – Hilonim and Haredim – experience the highest retention rates. The vast majority of those raised Haredim are still Haredim (94%), and nine-in-ten Jews raised Hilonim are still Hilonim.

The movement among Jewish subgroups in Israel is generally in the direction of lower observance. For example, while 54% of those raised as Datiim still identify as Datiim, most of the rest are now either Masortim (35%) or Hilonim (5%) – groups that are generally less observant than Datiim. And while two-thirds of those raised Masorti are still Masorti, most of those who have switched now identify as Hilonim (25% of all those raised Masorti).

Fewer Jews switch to groups with a higher level of observance than the one in which they were raised.

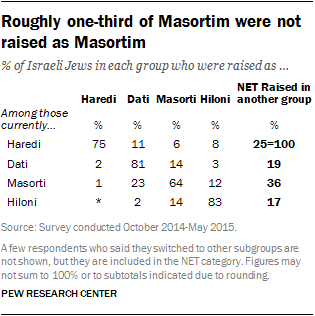

About one-in-five current Masortim were raised as Datiim

The flip side of examining retention rates is to consider which groups are most heavily made up of people who have switched into the group.

The flip side of examining retention rates is to consider which groups are most heavily made up of people who have switched into the group.

Jews who identify as Masortim have the highest share of switchers. Roughly one-third of Jews who currently identify as Masortim were not raised as Masortim (36%), including 23% who are former Datiim and 12% who are former Hilonim.

A quarter of current Haredim were raised in another Jewish subgroup, including 11% who were raised as Datiim and others who were raised as Masortim (6%) or Hilonim (8%).

Datiim and Hilonim are composed of 19% and 17% of switchers, respectively. Among each group, 14% of adults were raised Masorti.