The New, 114th Congress

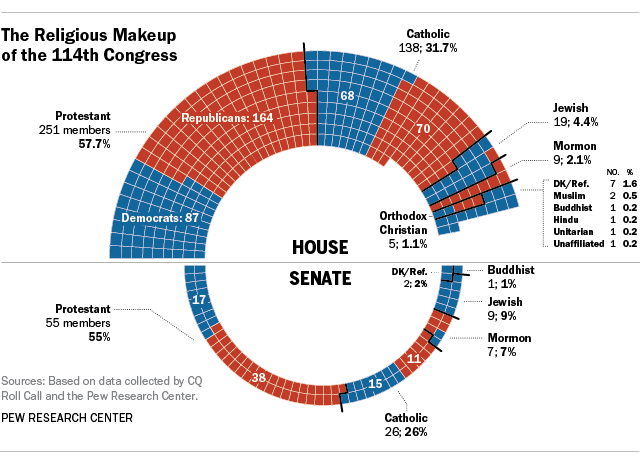

Pew Research surveys find that, as of 2013, about half of American adults (49%) identify as Protestant, but Congress remains majority Protestant. The percentage of Protestants in the new Congress (57%) is roughly the same as the percentage in the previous Congress (56%).

While the overall proportion of Protestants in Congress remains about the same, there are some modest changes within Protestant denominational families. For example, the number of Baptists in the new Congress increased by six, from 73 to 79, while the number of Lutherans rose by four, from 23 to 27. The number of Presbyterian members dropped by seven, from 43 to 36. This was the biggest drop, in numerical terms, among all the religious groups.

While the overall proportion of Protestants in Congress remains about the same, there are some modest changes within Protestant denominational families. For example, the number of Baptists in the new Congress increased by six, from 73 to 79, while the number of Lutherans rose by four, from 23 to 27. The number of Presbyterian members dropped by seven, from 43 to 36. This was the biggest drop, in numerical terms, among all the religious groups.

There is one more Catholic in the 114th Congress (164) than there was in the 113th. There are 16 Mormon members, one more than in the previous Congress. The number of Orthodox Christians (five) is unchanged.

Among non-Christian religious groups, Jews saw the largest losses, going from 33 members in the 113th Congress (6%) to 28 members (5%) in the 114th. The number of Jews in Congress is now nearly 40% lower than it was in the 111th Congress (2009-10), when there were 45 Jewish members.

The number of Buddhists in Congress fell from three to two, as Rep. Colleen Hanabusa, D-Hawaii, lost her bid for a Senate seat. Rep. Hank Johnson, D-Ga., who was re-elected, is now the lone Buddhist in the House of Representatives. In 2012, Mazie K. Hirono, D-Hawaii, became the first Buddhist elected to the Senate.

There were no changes in the number of Muslims (two), Hindus (one), Unitarian Universalists (one) or religiously unaffiliated people (one) serving in Congress. As noted above, Rep. Sinema of Arizona is the only member of Congress who identifies publicly as religiously unaffiliated. Rep. Ami Bera, D-Calif., is the only Unitarian Universalist, and Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, D-Hawaii, is the only Hindu. Both Muslim members of Congress – Rep. Keith Ellison, D-Minn., and Rep. Andre Carson, D-Ind. – were re-elected in 2014. Nine members (all Democrats) refused to specify their religious affiliation, one fewer than in the 113th Congress.

Differences by Chamber

Protestants as a whole make up roughly equal percentages of the House (58%) and Senate (55%). Most Protestant denominational families are represented in roughly equal proportions in both chambers, but there are a few exceptions. For example, Baptists, Episcopalians and Protestants who do not specify a denomination have higher representation in the House than in the Senate, while Presbyterians, Lutherans and Methodists are more heavily represented in the Senate than in the House.

Protestants as a whole make up roughly equal percentages of the House (58%) and Senate (55%). Most Protestant denominational families are represented in roughly equal proportions in both chambers, but there are a few exceptions. For example, Baptists, Episcopalians and Protestants who do not specify a denomination have higher representation in the House than in the Senate, while Presbyterians, Lutherans and Methodists are more heavily represented in the Senate than in the House.

Several other religious groups also have uneven representation in the two chambers. As was the case in the 113th Congress, Catholics make up a somewhat higher percentage of the House (32%) than the Senate (26%), while Mormons make up a larger share of the Senate (7%) than the House (2%). There are five Orthodox Christians in the House (1%), but none in the Senate.

All of Congress’ Muslim, Hindu, Unitarian Universalist and unaffiliated members serve in the House. (See section above for details.) One Buddhist serves in the House (Johnson of Georgia) and one in the Senate (Hirono of Hawaii).

Differences by Party Affiliation

Overall, 56% of the members of the new, 114th Congress are Republicans and 44% are (or caucus with) Democrats.

The study finds that two-thirds of congressional Republicans (67%) are Protestant, compared with 44% of Democrats. By comparison, Catholics make up a higher share of Democrats than Republicans (35% vs. 27%). Roughly 5% of all congressional Republicans are Mormons, compared with 1% of Democrats. Jews, on the other hand, account for nearly 12% of congressional Democrats but less than 1% of congressional Republicans.

First-Time Members

The new, 114th Congress has a relatively small freshman class of 71 – 16 fewer than in the 113th Congress and 41 fewer than in the 112th.2 Of the 114th’s first-time members, 55 are Republicans (77%).

The new, 114th Congress has a relatively small freshman class of 71 – 16 fewer than in the 113th Congress and 41 fewer than in the 112th.2 Of the 114th’s first-time members, 55 are Republicans (77%).

More than six-in-ten freshmen members are Protestant; in the 113th Congress, 48% of freshmen were Protestant. A few Protestant denominations – including Lutherans, Presbyterians and Protestants who do not specify a denomination – have a higher percentage of freshmen than incumbents. The same is true for Catholics, who represent 35% of freshmen and 30% of incumbents. Mormons are represented in about the same proportion among both freshmen and incumbents.

The only non-Christian freshman is Jewish Republican Rep. Zeldin of New York. In the 113th Congress, 13% of freshmen were non-Christians, including the first Hindu in the House or Senate, Democratic Rep. Gabbard of Hawaii, and four members who did not specify their religious affiliation.

Clergy in Congress

There are at least seven ordained ministers in the 114th Congress, all serving in the House of Representatives. Four are Republicans, and three are Democrats. (Some information on ordained ministers comes from the Congressional Research Service, which contacts members of Congress whose educational or occupational background suggests they might have been ordained.)

Four of the ordained ministers are Baptist (Doug Collins, R-Ga.; Jody Hice, R-Ga.; John Lewis, D-Ga.; and Mark Walker, R-N.C.); one is a Methodist (Emanuel Cleaver, D-Mo.); one is a Pentecostal (Bobby L. Rush, D-Ill.); and one is a Protestant who does not specify a denomination (Tim Walberg, R-Mich.). Walberg was ordained as a Baptist, but he now prefers to be identified as a Christian. Among all Protestant denominational families, Baptists have the largest representation in Congress (15%).

Two of the ordained ministers in the 114th Congress, Hice of Georgia and Walker of North Carolina, are freshmen. The rest were re-elected.

In addition to the ordained ministers in Congress, several members of the incoming Congress told CQ Roll Call that they have held religion-related occupations, including one senator, Oklahoma Republican James Lankford, who was director of a Baptist youth camp. In the House, Robert Pittenger, R-N.C., was a youth ministry organization manager, and Juan C. Vargas, D-Calif., was a Jesuit novice.

The overall number of ordained ministers in Congress has remained fairly steady over the last seven Congresses, ranging from a high of seven in the 114th Congress to a low of four in the 111th Congress. However, the tradition of clergy serving in Congress dates back to the early years of the Republic, as explored in a sidebar to this report.

Looking Back

Although Congress remains predominantly Christian and majority Protestant, it is more religiously diverse than it was in the 1960s and ’70s.

Comparing the 114th Congress with the 87th (1961-1962), for example, the share of Protestants is down by 18 percentage points, while the share of Catholics is up by 12 points. The percentage of Jewish members in Congress is up 3 points.

One thing has not changed, however: Even though the percentage of U.S. adults identifying as religious “nones” has grown in recent decades, the congressional representation of the unaffiliated continues to lag behind. As noted earlier, only one member of the new Congress identifies as religiously unaffiliated. And over the past five decades, only one member has publicly declared that he does not believe in God or a Supreme Being: Rep. Pete Stark, D-Calif., who served in Congress from 1973-2012.