Most Hispanics in the United States continue to belong to the Roman Catholic Church. But the Catholic share of the Hispanic population is declining, while rising numbers of Hispanics are Protestant or unaffiliated with any religion. Indeed, nearly one-in-four Hispanic adults (24%) are now former Catholics, according to a major, nationwide survey of more than 5,000 Hispanics by the Pew Research Center. Together, these trends suggest that some religious polarization is taking place in the Hispanic community, with the shrinking majority of Hispanic Catholics holding the middle ground between two growing groups (evangelical Protestants and the unaffiliated) that are at opposite ends of the U.S. religious spectrum.

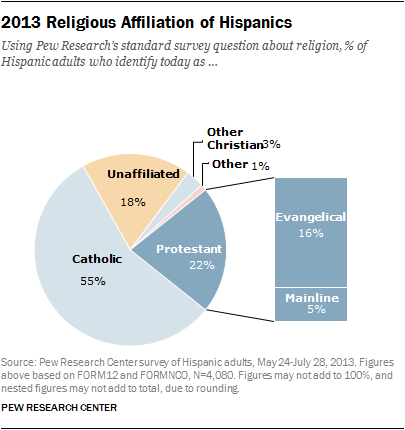

The Pew Research Center’s 2013 National Survey of Latinos and Religion finds that a majority (55%) of the nation’s estimated 35.4 million Latino adults – or about 19.6 million Latinos – identify as Catholic today. 1 About 22% are Protestant (including 16% who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical) and 18% are religiously unaffiliated.

The Pew Research Center’s 2013 National Survey of Latinos and Religion finds that a majority (55%) of the nation’s estimated 35.4 million Latino adults – or about 19.6 million Latinos – identify as Catholic today. 1 About 22% are Protestant (including 16% who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical) and 18% are religiously unaffiliated.

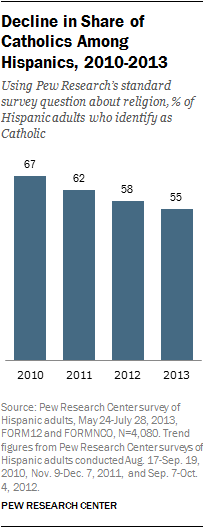

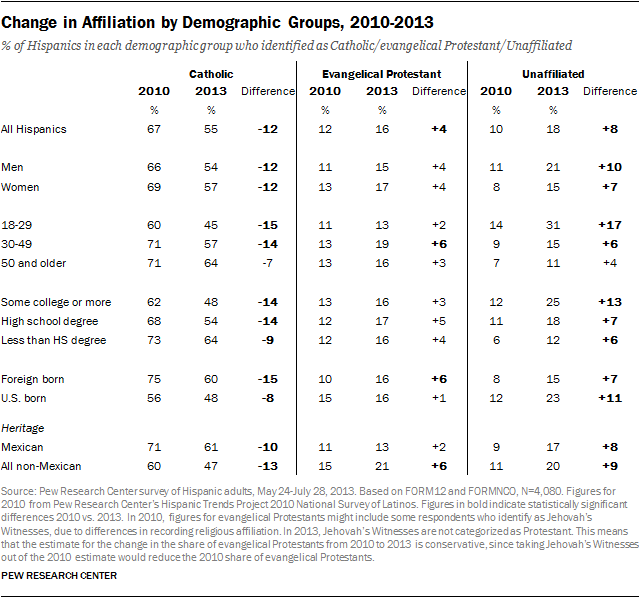

The share of Hispanics who are Catholic likely has been in decline for at least the last few decades.2 But as recently as 2010, Pew Research polling found that fully two-thirds of Hispanics (67%) were Catholic. That means the Catholic share has dropped by 12 percentage points in just the last four years, using Pew Research’s standard survey question about religious affiliation.3

The long-term decline in the share of Catholics among Hispanics may partly reflect religious changes underway in Latin America, where evangelical churches have been gaining adherents and the share of those with no religious affiliation has been slowly rising in a region that historically has been overwhelmingly Catholic.4 But it also reflects religious changes taking place in the U.S., where Catholicism has had a net loss of adherents through religious switching (or conversion) and the share of the religiously unaffiliated has been growing rapidly in the general public.5

The long-term decline in the share of Catholics among Hispanics may partly reflect religious changes underway in Latin America, where evangelical churches have been gaining adherents and the share of those with no religious affiliation has been slowly rising in a region that historically has been overwhelmingly Catholic.4 But it also reflects religious changes taking place in the U.S., where Catholicism has had a net loss of adherents through religious switching (or conversion) and the share of the religiously unaffiliated has been growing rapidly in the general public.5

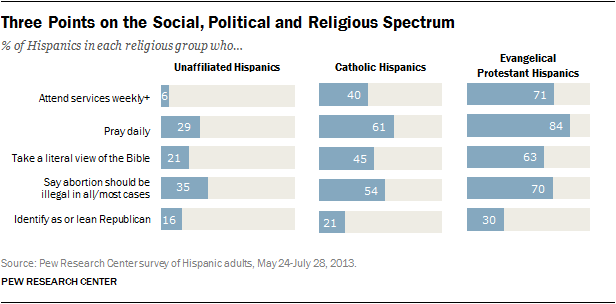

Hispanics leaving Catholicism have tended to move in two directions. Some have become born-again or evangelical Protestants, a group that exhibits very high levels of religious commitment. On average, Hispanic evangelicals – many of whom also identify as either Pentecostal or charismatic Protestants – not only report higher rates of church attendance than Hispanic Catholics but also tend to be more engaged in other religious activities, including Scripture reading, Bible study groups and sharing their faith.

At the same time, other Hispanics have become religiously unaffiliated – that is, they describe themselves as having no particular religion or say they are atheist or agnostic. This group exhibits much lower levels of religious observance and involvement than Hispanic Catholics. In this respect, unaffiliated Hispanics roughly resemble the religiously unaffiliated segment of the general public.

Hispanic Catholics are somewhere in the middle. They fall in between evangelicals and the unaffiliated in terms of church attendance, frequency of prayer and the degree of importance they assign to religion in their lives, closely resembling white (non-Hispanic) Catholics in their moderate levels of religious observance and engagement (see Chapter 3).

These three Hispanic religious groups also have distinct social and political views, with evangelical Protestants at the conservative end of the spectrum, the unaffiliated at the liberal end and Hispanic Catholics in between.

These are among the key findings of the Pew Research Center’s 2013 National Survey of Latinos and Religion. The survey was conducted May 24-July 28, 2013, among a representative sample of 5,103 Hispanic adults (ages 18 and older) living in the United States. The survey was conducted in English and in Spanish on both cellular and landline telephones with a staff of bilingual interviewers. The margin of error for results based on all respondents is plus or minus 2.1 percentage points. For more details, see Appendix A: Survey Methodology.

The remainder of this overview discusses the key findings in greater detail, beginning with a deeper look at changes in religious affiliation among Latinos in recent years, which have been concentrated among young and middle-aged adults (ages 18-49). While these shifts are complicated and defy any single, simple explanation, the report examines some potential factors, including patterns in religious switching since childhood, the reasons Latinos most frequently give for changing their religion, areas of agreement and disagreement with the Catholic Church, and the continuing appeal of Pentecostalism. The report also explores key differences between Latino religious groups, placing Latino Protestants, Catholics and religiously unaffiliated adults on a spectrum in terms of religious commitment, social attitudes and political views.

Broad-Based Changes in Religious Identity

The recent changes in religious affiliation are broad-based, occurring among Hispanic men and women, those born in the United States and those born abroad, and those who have attended college as well as those with less formal education. The changes are also occurring among Hispanics of Mexican origin (the largest single origin group) and those with other origins.

The change, however, has occurred primarily among Hispanic adults under the age of 50, and the patterns vary considerably among different age groups. Among the youngest cohort of Hispanic adults, those ages 18-29, virtually all of the net change has been away from Catholicism and toward no religious affiliation. Among those ages 30-49, the net movement has been away from Catholicism and toward both evangelical Protestantism and no religious affiliation. Among Hispanics ages 50 and older, the changes in religious identity are not statistically significant.

For more on religious affiliation, see Chapter 1.

Latinos Make Up a Rising Share of Catholics

Even though the percentage of Hispanics who identify as Catholic has been declining, Hispanics continue to make up an increasingly large share of U.S. Catholics. Indeed, as of 2013, one-third (33%) of all U.S. Catholics were Hispanic, according to Pew Research surveys.

Even though the percentage of Hispanics who identify as Catholic has been declining, Hispanics continue to make up an increasingly large share of U.S. Catholics. Indeed, as of 2013, one-third (33%) of all U.S. Catholics were Hispanic, according to Pew Research surveys.

Both trends can occur at the same time because of the growing size of the Hispanic population, which has increased from 12.5% of the total U.S. population in 2000 to 16.9% in 2012. Indeed, if both trends continue, a day could come when a majority of Catholics in the United States will be Hispanic, even though the majority of Hispanics might no longer be Catholic.

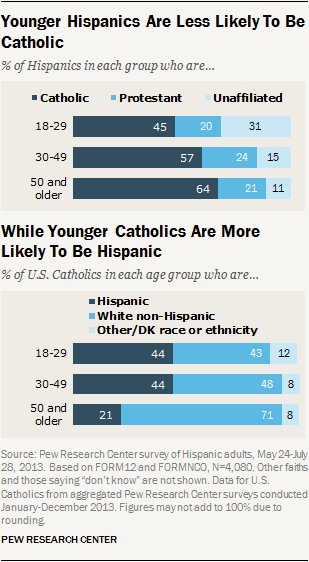

While the decline in Catholic affiliation is occurring among multiple age groups, it is more pronounced among younger generations of Hispanics. Today, fewer than half of Hispanics under age 30 are Catholic (45%), compared with about two-thirds of those ages 50 and older (64%).

At the same time, Catholics under age 50 are much more likely to be Hispanic than those ages 50 and older (44% vs. 21%).

Religious Switching Since Childhood

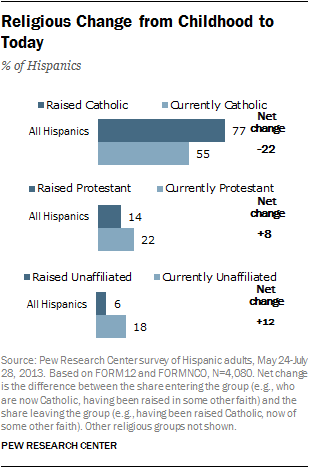

The decline in Catholic affiliation among Latinos is due, at least in part, to changes in religious affiliation since childhood.6 Three-quarters of Latino adults in the new survey (77%) say they were raised as Catholics, while just over half (55%) currently describe themselves as Catholics. Roughly a quarter of Latinos were raised Catholic and have left the faith (24%), while just 2% were raised in some other faith and have converted to Catholicism, for a net decline of 22 percentage points.

The decline in Catholic affiliation among Latinos is due, at least in part, to changes in religious affiliation since childhood.6 Three-quarters of Latino adults in the new survey (77%) say they were raised as Catholics, while just over half (55%) currently describe themselves as Catholics. Roughly a quarter of Latinos were raised Catholic and have left the faith (24%), while just 2% were raised in some other faith and have converted to Catholicism, for a net decline of 22 percentage points.

Catholicism is the only major religious tradition among Latinos that has seen a net loss in adherents due to religious switching. Net gains have occurred among the religiously unaffiliated (up 12 percentage points) and among Protestants (up eight points).

Foreign Born

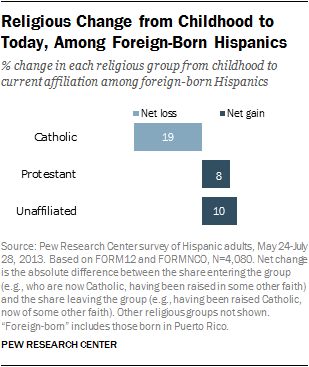

Roughly half of Hispanic adults (50%) were born outside the United States. 7 Among these first-generation immigrants, Catholics have had a net loss of 19 percentage points due to religious switching. The net gains are about evenly divided between those who have changed to Protestant (a net gain of eight percentage points) and those who have changed to no religious affiliation (a net gain of 10 percentage points).

Roughly half of Hispanic adults (50%) were born outside the United States. 7 Among these first-generation immigrants, Catholics have had a net loss of 19 percentage points due to religious switching. The net gains are about evenly divided between those who have changed to Protestant (a net gain of eight percentage points) and those who have changed to no religious affiliation (a net gain of 10 percentage points).

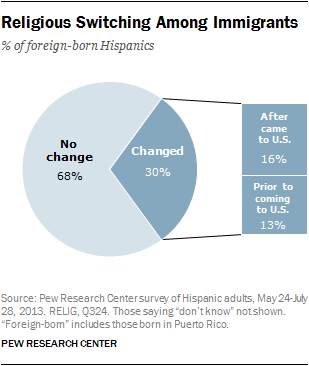

Among Hispanic immigrants who say their current religion is different from their childhood religion, roughly half say this change occurred after moving to the U.S., while nearly as many say they changed religion before coming to the United States.

Among Hispanic immigrants who say their current religion is different from their childhood religion, roughly half say this change occurred after moving to the U.S., while nearly as many say they changed religion before coming to the United States.

U.S. Born

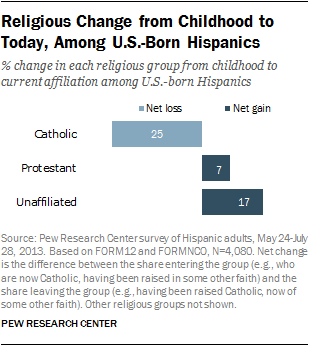

At the same time, a growing share of Hispanics were born in the U.S., and they are gradually shifting the demographic center of gravity in the Hispanic community from immigrants to the U.S. born.8 Looking at religious switching among the native born, the biggest gains have been among the unaffiliated (a net gain of 17 percentage points) and Protestants (a net gain of seven points). Catholics, by contrast, have had a net loss of 25 percentage points among the native born.

At the same time, a growing share of Hispanics were born in the U.S., and they are gradually shifting the demographic center of gravity in the Hispanic community from immigrants to the U.S. born.8 Looking at religious switching among the native born, the biggest gains have been among the unaffiliated (a net gain of 17 percentage points) and Protestants (a net gain of seven points). Catholics, by contrast, have had a net loss of 25 percentage points among the native born.

For more on religious switching, see Chapter 2.

Reasons Given for Switching Religions

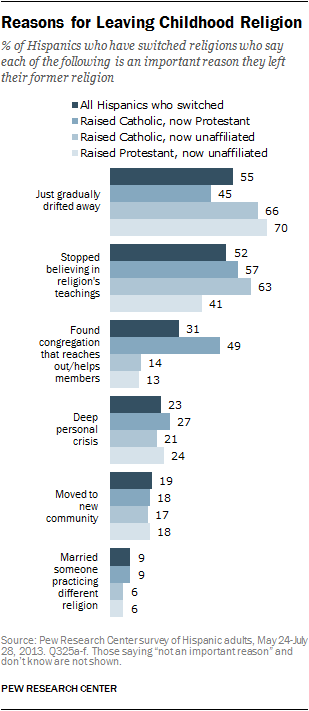

The new survey asked respondents who have left their childhood religion about the reasons they did so. Of six possible reasons offered on the survey, two were cited as important by half or more of Hispanics who have changed faiths: 55% say they just gradually “drifted away” from the religion in which they were raised, and 52% say they stopped believing in the teachings of their childhood religion.

The new survey asked respondents who have left their childhood religion about the reasons they did so. Of six possible reasons offered on the survey, two were cited as important by half or more of Hispanics who have changed faiths: 55% say they just gradually “drifted away” from the religion in which they were raised, and 52% say they stopped believing in the teachings of their childhood religion.

In addition, nearly a third (31%) say they found a congregation that reaches out and helps its members more, while roughly a fifth say the decision was associated with a “deep personal crisis” (23%) or with moving to a new community (19%). About one-in-ten (9%) say that marrying someone who practices a different faith was an important reason for leaving their childhood religion.

Latinos who have left the Catholic Church are especially likely to say that an important reason was that they stopped believing in its teachings; 63% of former Catholics who are now unaffiliated and 57% of former Catholics who are now Protestants give this reason for having left the church.

In addition, 49% of Hispanics who were raised as Catholics and have become Protestants say that an important factor was finding a church that “reaches out and helps its members more.”

The survey also contained an open-ended question asking respondents to explain, in their own words, the main reason they left their childhood religion. Some former Catholics cite particular aspects of Catholicism that they now reject, such as the veneration of saints and the Virgin Mary, or trust in the Catholic priesthood; about 3% specifically mention the scandal over sexual abuse by clergy, for example. But many others give general answers, such as that they no longer accept Catholic doctrine, came to a different understanding of the Bible, found God’s love, lost faith in all religions or decided for themselves what to believe.

For more on the reasons Hispanics give for switching faiths, see Chapter 2.

For an analysis of the extent to which childhood Catholics who have switched faiths or become religiously unaffiliated retain vestiges of Catholic beliefs and practices, such as praying to the Virgin Mary and displaying a crucifix or other religious objects in their home, see Chapter 4.

Attitudes of Current and Former Catholics Toward the Catholic Church

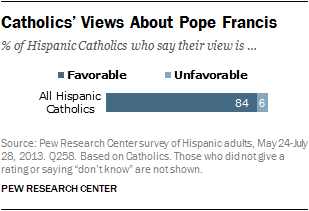

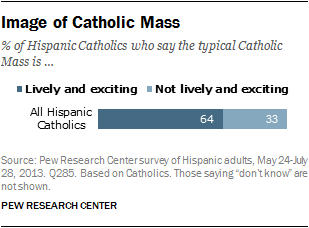

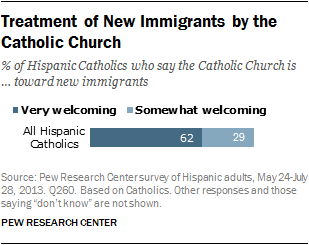

On the whole, Hispanic Catholics express very positive views of some aspects of their church. For example, more than eight-in-ten say their opinion of Pope Francis is either very favorable (45%) or mostly favorable (38%).9 Nearly two-thirds (64%) say they consider the typical Catholic Mass to be “lively and exciting.” And about six-in-ten Hispanic Catholics (62%) consider the Catholic Church to be very welcoming to new immigrants. An additional three-in-ten (29%) say it is somewhat welcoming; just 5% say it is “not too” welcoming or “not at all” welcoming to immigrants. Foreign-born and U.S.-born Catholics are about equally likely to see the Catholic Church as welcoming toward immigrants.

On the whole, Hispanic Catholics express very positive views of some aspects of their church. For example, more than eight-in-ten say their opinion of Pope Francis is either very favorable (45%) or mostly favorable (38%).9 Nearly two-thirds (64%) say they consider the typical Catholic Mass to be “lively and exciting.” And about six-in-ten Hispanic Catholics (62%) consider the Catholic Church to be very welcoming to new immigrants. An additional three-in-ten (29%) say it is somewhat welcoming; just 5% say it is “not too” welcoming or “not at all” welcoming to immigrants. Foreign-born and U.S.-born Catholics are about equally likely to see the Catholic Church as welcoming toward immigrants.

In general, the survey finds that former Catholics tend to be less positive on these questions. Though a plurality (50%) of Hispanics who were raised as Catholics and have since left the church hold favorable opinions of Pope Francis, a larger share of former Catholics than current Catholics express an unfavorable view of the pontiff (21% vs. 6%) or do not state an opinion (29% vs. 5%). Only one-third of Hispanics who have left the faith say the Catholic Church is very welcoming toward new immigrants (33%), and just one-in-five think the typical Mass is lively and exciting (19%). However, these are classic chicken-and-egg situations: it is impossible to know whether such views are a cause of religious switching or a consequence of having switched.

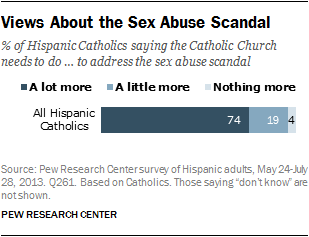

Even as Latino Catholics generally express positive views of their church, there is strong consensus among them that more action is needed to address the clergy sex abuse scandal. About three-quarters of the current Catholics surveyed say the church needs to do “a lot more” (74%) to address the scandal; just 4% say the church does not need to do anything more to address the sex abuse issue.

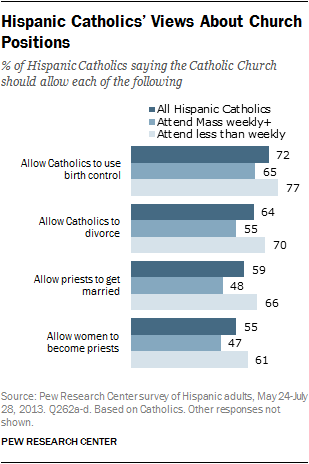

Moreover, most Hispanic Catholics are at odds with the church’s teachings on divorce and contraception, and most favor allowing priests to marry and women to become priests. Disagreement with these church teachings is stronger among Hispanic Catholics who attend Mass less regularly. But even among weekly Mass attenders, about half or more support changing the church’s positions on these issues.10 (Questions about whether the Catholic Church should change its positions were asked only of Catholics.)

Continuing Appeal of Pentecostalism

One of the main findings of the first major Pew Research survey of Latinos and religion, conducted in 2006 and released in 2007, was the strong influence of Pentecostalism and related “charismatic” or “spirit-filled” religious movements, which have been burgeoning in Latin America and other countries in the “global South” for the past century or so.11 Those who belong to this diverse and dynamic branch of Christianity are sometimes referred to as “renewalists” because of their belief in the spiritually renewing gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as speaking in tongues, divine healing and prophesying. They also nurture a strong sense of God’s direct, often miraculous, role in everyday life.

The influence of Pentecostalism is still strongly felt within the Hispanic community. The new survey finds that among Hispanics who have left Catholicism and now identify as Protestants, more than a quarter (28%) are Pentecostal. Among Hispanic Protestants overall, two-thirds either say they belong to a traditional Pentecostal denomination (29%) or describe themselves as charismatic or Pentecostal Christians (38%). Among Hispanic Catholics, 52% describe themselves as charismatic Christians. (For definitions of terms, see Chapter 7.)

The influence of Pentecostalism is still strongly felt within the Hispanic community. The new survey finds that among Hispanics who have left Catholicism and now identify as Protestants, more than a quarter (28%) are Pentecostal. Among Hispanic Protestants overall, two-thirds either say they belong to a traditional Pentecostal denomination (29%) or describe themselves as charismatic or Pentecostal Christians (38%). Among Hispanic Catholics, 52% describe themselves as charismatic Christians. (For definitions of terms, see Chapter 7.)

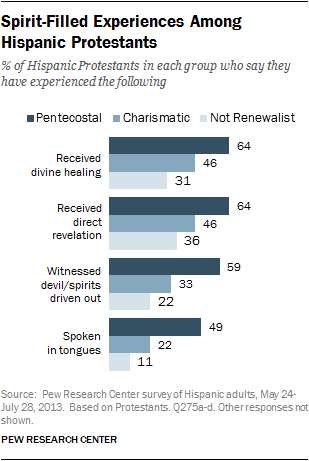

Hispanics who are Pentecostals are particularly likely to report having received a divine healing (64%) or a direct revelation from God (64%), to have witnessed the devil or spirits being driven out of a person (59%), and to say they have spoken in tongues (49%). And those who describe themselves as charismatics are more likely than those who do not describe themselves as renewalist Christians to have witnessed or participated in these types of experiences. For more on renewalism among both Protestants and Catholics, see Chapter 7. In addition, Chapter 8 looks at the influence of indigenous or Afro-Caribbean religions and the importance of the spirit world in Hispanics’ everyday lives.

Measures of Religious Commitment

As the religious diversity of Latinos grows, the major religious groups are marked by sharply differing levels of religious commitment.

As the religious diversity of Latinos grows, the major religious groups are marked by sharply differing levels of religious commitment.

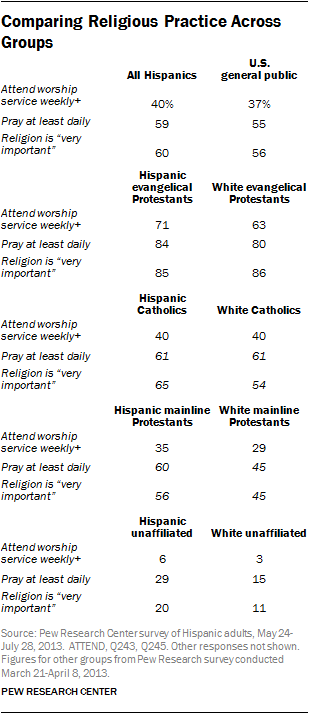

Latino evangelical Protestants are the most likely to say they attend worship services at least weekly, pray daily and consider religion to be very important in their lives. Religiously unaffiliated Latinos are at the other end of the spectrum, with just 6% reporting that they attend services weekly and a minority saying that religion is very important to them (20%) or that they pray daily (29%). Latino Catholics and mainline Protestants fall in the middle between these two groups.

With few exceptions, Hispanic religious groups are similar to their non-Hispanic counterparts in the general public in terms of religious commitment. The main exception is Hispanic mainline Protestants, who tend to be somewhat more religious, by conventional measures, than white (non-Hispanic) mainline Protestants. The differences stem primarily from higher levels of religious practice among foreign-born mainliners. U.S.-born Hispanic mainline Protestants resemble white (non-Hispanic) mainline Protestants in their levels of religious commitment. For more on religious commitment and practices, including engagement in congregational life, see Chapter 3.

Social and Political Views

When it comes to social and political views, Hispanics also fall into distinct groups along religious lines.

Same-Sex Marriage

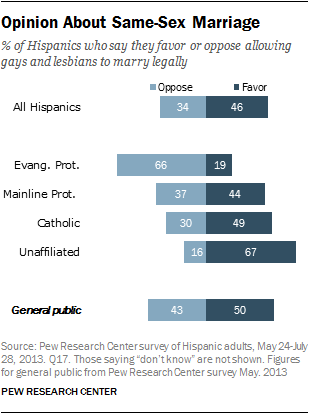

Like the U.S. public as a whole, Latinos have become more inclined to favor same-sex marriage in recent years; support among Latinos has risen from 30% in 2006 to 46% in 2013. However, there still are sizable differences in views about same-sex marriage among Hispanic religious groups. Religiously unaffiliated Hispanics favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally by a roughly four-to-one margin (67% to 16%). Hispanic Protestants tilt in the opposite direction, with evangelical Protestants much more inclined to oppose same-sex marriage (66% opposed, 19% in favor). Hispanic Catholics fall in between, though more say they favor same-sex marriage (49%) than oppose it (30%). Mainline Protestants are closely divided on the issue, with nearly four-in-ten (37%) opposed to same-sex marriage and 44% in favor. These differences among Hispanic religious groups are largely in keeping with patterns found among the same religious groups in the general public.12

Like the U.S. public as a whole, Latinos have become more inclined to favor same-sex marriage in recent years; support among Latinos has risen from 30% in 2006 to 46% in 2013. However, there still are sizable differences in views about same-sex marriage among Hispanic religious groups. Religiously unaffiliated Hispanics favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally by a roughly four-to-one margin (67% to 16%). Hispanic Protestants tilt in the opposite direction, with evangelical Protestants much more inclined to oppose same-sex marriage (66% opposed, 19% in favor). Hispanic Catholics fall in between, though more say they favor same-sex marriage (49%) than oppose it (30%). Mainline Protestants are closely divided on the issue, with nearly four-in-ten (37%) opposed to same-sex marriage and 44% in favor. These differences among Hispanic religious groups are largely in keeping with patterns found among the same religious groups in the general public.12

Abortion

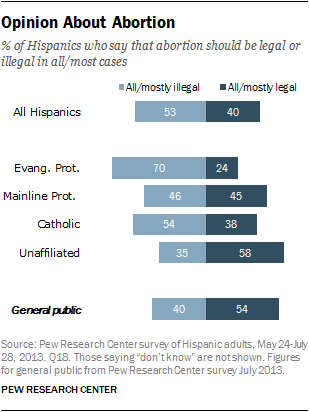

Hispanics tend to be more conservative than the general public in their views on abortion. While 54% of U.S. adults say that abortion should be legal in all or most circumstances, just four-in-ten Hispanics take this position.

Hispanics tend to be more conservative than the general public in their views on abortion. While 54% of U.S. adults say that abortion should be legal in all or most circumstances, just four-in-ten Hispanics take this position.

But Latino religious groups differ markedly in their views about abortion. Most Latino evangelical Protestants (70%) say that abortion should be illegal in all or most circumstances, as do 54% of Latino Catholics. Latino mainline Protestants are closely divided, with 45% saying abortion should be mostly legal and 46% saying it should be mostly illegal. And a majority of religiously unaffiliated Hispanics (58%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

Views on abortion among Hispanic evangelical Protestants are similar to those among white (non-Hispanic) evangelicals, 64% of whom say that abortion should be illegal in all or most circumstances. Hispanic Catholics are more inclined than white Catholics to say that abortion should be illegal (54% vs. 44%). Hispanic mainline Protestants are also more inclined than white mainline Protestants to say that abortion should be illegal in all or most circumstances (46% vs. 31%).13 The belief that abortion should be illegal in all or most cases is more common among those who attend religious services at least once a week.

Religion in Politics

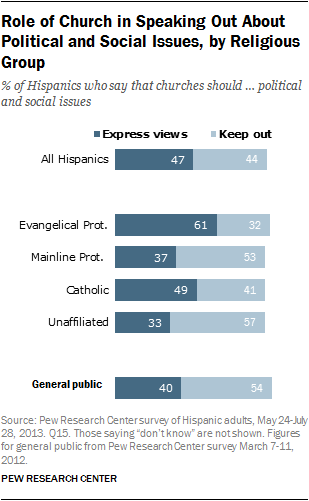

Latinos are closely divided over the role that churches and other houses of worship should play in public debates over social and political issues. While 47% say that churches should express their views on social and political issues, a similar share (44%) say they should not. In the general public, more Americans say that churches should keep out of politics (54% to 40%), according to a 2012 Pew Research survey.

Latinos are closely divided over the role that churches and other houses of worship should play in public debates over social and political issues. While 47% say that churches should express their views on social and political issues, a similar share (44%) say they should not. In the general public, more Americans say that churches should keep out of politics (54% to 40%), according to a 2012 Pew Research survey.

But, once again, there are sizable differences of opinion among Hispanic religious groups. About six-in-ten Hispanic evangelical Protestants (61%) say that church leaders should express their views on social and political issues, while about a third say church leaders should keep out of political matters. By contrast, half or more of religiously unaffiliated and mainline Protestant Hispanics say that church leaders should stay out of political matters. Hispanic Catholics are more divided on this issue, with about half (49%) saying church leaders should express their views and 41% saying church leaders should keep out of political matters.

Gender Roles

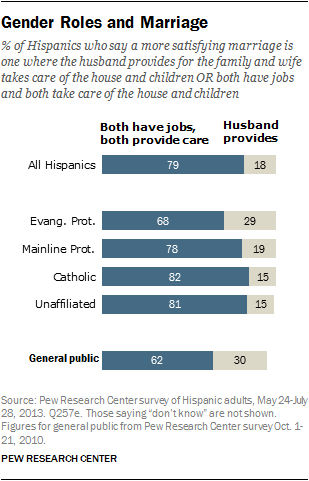

Solid majorities of Hispanics in all major religious groups reject traditional views of gender roles within marriage. Most say that a marriage in which both husband and wife hold jobs and help take care of the children (79%) is preferable to a traditional arrangement where the husband is the financial provider and the wife takes care of the house and children (18%). Further, about six-in-ten Hispanics (63%) reject the idea that “husbands should have the final say in family matters” – though fully one-third (34%) say husbands should have final say. Overall, Hispanics are no more likely to prefer traditional marriage roles than the general public was in a 2010 Pew Research survey that asked many of the same questions.14 And there are few significant differences of opinion about marital roles among Hispanics by gender, age or immigrant generation.

Solid majorities of Hispanics in all major religious groups reject traditional views of gender roles within marriage. Most say that a marriage in which both husband and wife hold jobs and help take care of the children (79%) is preferable to a traditional arrangement where the husband is the financial provider and the wife takes care of the house and children (18%). Further, about six-in-ten Hispanics (63%) reject the idea that “husbands should have the final say in family matters” – though fully one-third (34%) say husbands should have final say. Overall, Hispanics are no more likely to prefer traditional marriage roles than the general public was in a 2010 Pew Research survey that asked many of the same questions.14 And there are few significant differences of opinion about marital roles among Hispanics by gender, age or immigrant generation.

However, Latino evangelical Protestants are somewhat more likely than either Latino Catholics or religiously unaffiliated Latinos to say a traditional marriage is a more satisfying way of life (29% vs. 15% each).

And Latino Protestants – including mainline as well as evangelical Protestants – are more inclined than either Catholics or the religiously unaffiliated to believe that husbands should have the final say on family matters. Latinos who attend services more regularly are more inclined to say this than are those who attend less frequently.

Partisanship

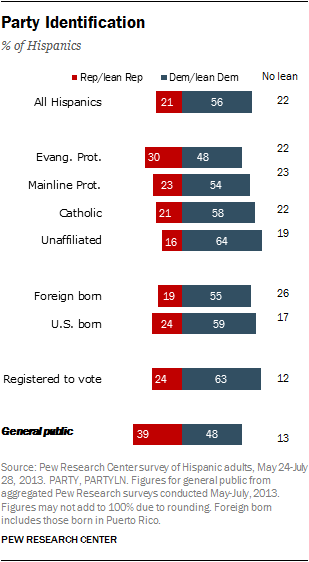

Hispanics are more unified when it comes to party identification. Across all of the major religious groups, Hispanics are more likely to identify with the Democratic Party than with the Republican Party. Overall, 56% of Hispanics describe themselves as Democrats or as independents who lean toward the Democratic Party. About a fifth (21%) identify with or lean toward the Republican Party, and about a fifth (22%) do not lean toward either party.

Hispanics are more unified when it comes to party identification. Across all of the major religious groups, Hispanics are more likely to identify with the Democratic Party than with the Republican Party. Overall, 56% of Hispanics describe themselves as Democrats or as independents who lean toward the Democratic Party. About a fifth (21%) identify with or lean toward the Republican Party, and about a fifth (22%) do not lean toward either party.

The partisan gap is narrower among Latino evangelicals than among other religious groups. Three-in-ten Latino evangelical Protestants identify as Republicans or lean toward the Republicans, while 48% identify with or lean toward the Democrats. The religiously unaffiliated are particularly likely to identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party (64%) over the Republican Party (16%). Latino Catholics also tilt more heavily toward the Democrats (58%) than toward the GOP (21%).

About half or more of both foreign-born and U.S.-born Hispanics identify as Democrats or as independents who lean toward the Democratic Party. However, those who are foreign born – including some who are not U.S. citizens – are less likely to express a party affiliation than those who are U.S. born.

For more on views about social and political issues, see Chapter 9.

About the Survey

Religious Affiliation

Religious affiliation is based on self-identification into religious groups.

For the purposes of this analysis, evangelical Protestants are those who describe themselves as being a “born-again” or evangelical Christian. All other Protestants are classified as “mainline Protestants.”

Other Christian groups include those who identify as Mormons, Orthodox Christians and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Note that figures for the general public (but not for Hispanics) include Jehovah’s Witnesses as Protestants due to the way questions about religious affiliation have been asked in prior surveys. The overall effect on estimates of Protestants in the general public is quite small because Jehovah’s Witnesses make up less than 1% of the general public.

This report is based on findings from a Pew Research Center survey conducted May 24-July 28, 2013, among a nationally representative sample of 5,103 Hispanic adults. The survey was conducted in both English and Spanish on cellular as well as landline telephones. The margin of error for the full sample is plus or minus 2.1 percentage points at the 95% confidence interval. Interviews were conducted for Pew Research by Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS). For a detailed description of the methodology, see Appendix A.

Estimates of the current religious profile of Hispanics are based on 4,080 respondents who were asked the standard Pew Research question on religious affiliation, which has been used in numerous U.S. surveys since 2007.15 For more details on the current religious affiliation of Hispanics, see Chapter 1.

Estimates of change in religious affiliation from 2010 to 2013 are based on Pew Research surveys that use the same standard question about religious affiliation.

Pew Research’s first major survey of Hispanics and religion, conducted in 2006 and released in 2007, used a slightly different question on religious affiliation. To allow for a direct comparison with that survey, a random subsample of 1,023 respondents in the new survey were asked about their religious affiliation using the 2006 question wording. For more details, see the sidebar in Chapter 1.

Other analyses throughout this report are based on the full, combined sample (N=5,103).

Many Pew Research staff members contributed to the development of this survey and accompanying report. Jessica Hamar Martinez and Cary Funk were the principal researchers on this survey and lead authors of the report. They were assisted by Greg Smith, Associate Director of Religion Research. Elizabeth Sciupac contributed to the data analysis, writing and number checking. Juan Carlos Esparza Ochoa and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera also assisted with questionnaire development and analysis, and Besheer Mohamed and Angelina Theodorou helped with number checking. Sandra Stencel, Tracy Miller and Michael Lipka provided editorial review and copy editing. Others who contributed to the report include Erin O’Connell, Anna Brown, Noble Kuriakose, Joseph Liu, Eileen Patten, Katherine Ritchey, Stacy Rosenberg and Bill Webster. Fieldwork for the survey was ably carried out by Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS) under the direction of David Dutwin. The questionnaire and analysis benefited from the guidance of a number of others at the Pew Research Center, especially the center’s director of Hispanic research, Mark Hugo Lopez, as well as Claudia Deane, Michael Dimock and Alan Murray. Expert advice on portions of the questionnaire was provided by R. Andrew Chesnut of Virginia Commonwealth University, Joseph M. Murphy of Georgetown University and Timothy J. Steigenga of Florida Atlantic University. All these efforts were guided by Luis Lugo, former director of the Religion & Public Life Project, and the current director, Alan Cooperman.

Pew Research previously released two other reports in October 2013 based on this survey: “Latinos’ Views of Illegal Immigration’s Impact on Their Community Improve” and “Three-Fourths of Hispanics Say Their Community Needs a Leader.”

Roadmap to the Report

The remainder of this report details the survey’s findings on Latinos and religion. Chapter 1 looks at the religious affiliation of Hispanics, including religious profiles of the major Hispanic origin groups in the United States. Chapter 2 covers religious switching among Hispanics as well as reasons for leaving one’s childhood religion. Chapter 3 describes religious commitment and religious practices, including frequency of attendance at worship services, frequency of prayer and involvement in church activities aside from worship services. Chapter 4 examines Hispanics’ views of Pope Francis and of the Catholic Church more broadly. Chapter 5 discusses the ethnic characteristics of the churches that Hispanics attend, including the availability of Spanish-language worship services, the presence of Hispanic clergy and the presence of other Hispanic churchgoers. Chapter 6 explores religious beliefs, including beliefs about the Bible, the Virgin Mary and the prosperity gospel. Chapter 7 examines renewalism among Hispanics, including the beliefs and practices of those who identify as Pentecostal and charismatic Protestants and Catholics. Chapter 8 takes a closer look at the experience of the spirit world. Chapter 9 covers views on social and political issues, such as abortion, same-sex marriage, gender expectations and the role of the church in political matters.

Terms and Definitions

The terms “Latino” and “Hispanic” are used interchangeably in this report.

“U.S. born” and “native born” refer to persons who were born in the United States.

“Foreign born” refers to persons born outside of the United States, and includes those born in Puerto Rico. While those born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens by birth, they are classified in this report for analysis with others born into a Spanish-dominant culture.

“First generation” refers to foreign-born people. The terms “foreign born,” “first generation” and “immigrant” are used interchangeably in this report.

“Second generation” refers to people born in the United States, with at least one first-generation parent.

“Third and higher generation” refers to people born in the United States, with both parents born in the United States. This report uses the term “third generation” as shorthand for “third and higher generation.”

Language dominance, or primary language, is a composite measure based on self-described assessments of speaking and reading abilities. “Spanish-dominant” persons are more proficient in Spanish than in English, i.e., they speak and read Spanish “very well” or “pretty well” but rate their English-speaking and reading ability lower. “Bilingual” refers to persons who are proficient in both English and Spanish. “English-dominant” persons are more proficient in English than in Spanish.

U.S. Hispanic groups, subgroups, heritage groups and country-of-origin groups are used interchangeably to refer to a respondent’s self-classification into the group best describing “you and your family’s heritage.” This self-identification may or may not match a respondent’s country of birth or their parent’s country of birth.

Racial and ethnic groups are classified as follows unless otherwise noted: whites include only non-Hispanic whites; blacks include only non-Hispanic blacks; Hispanics are of any race.

Some trend figures in this report may differ from past publications due to differences in classifying religious groups.