U.S. Jews see being Jewish as more a matter of ancestry, culture and values than of religious observance. Six-in-ten say, for example, that being Jewish is mainly a matter of culture or ancestry, compared with 15% who say it is mainly a matter of religion. Roughly seven-in-ten say remembering the Holocaust and leading an ethical life are essential to what it means to them to be Jewish, while far fewer say observing Jewish law is a central component of their Jewish identity. And two-thirds of Jews say that a person can be Jewish even if he or she does not believe in God.

To be sure, there are big differences among Jews about what it means to be Jewish. For instance, Orthodox Jews generally attach much more importance to the religious elements of being Jewish. And for Jews by religion, caring about Israel is much more central than it is for Jews of no religion.

There also are vast differences between Jews by religion and Jews of no religion in their level of involvement in Jewish organizations, in their self-reported ability to speak and understand Hebrew, and in their approach to child rearing. In all of these areas, Jews by religion are much more connected to their Jewish heritage than are Jews of no religion.

Denominational Identity

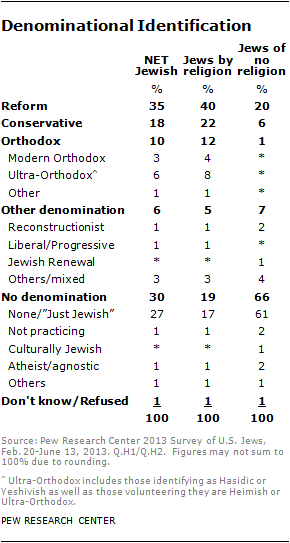

More than one-third of U.S. Jews (35%) identify with the Reform movement. About one-in-five (18%) identify with the Conservative movement. One-in-ten Jews identify with Orthodox Judaism (10%), including 6% who belong to Ultra-Orthodox groups and 3% who are Modern Orthodox. Three-in-ten Jews (30%) do not identify with any particular Jewish denomination. The remainder (7%) identify with smaller movements (such as Reconstructionism or the Jewish Renewal movement), say they belong to more than one movement (such as both Conservative and Orthodox), or decline to answer the question.

More than one-third of U.S. Jews (35%) identify with the Reform movement. About one-in-five (18%) identify with the Conservative movement. One-in-ten Jews identify with Orthodox Judaism (10%), including 6% who belong to Ultra-Orthodox groups and 3% who are Modern Orthodox. Three-in-ten Jews (30%) do not identify with any particular Jewish denomination. The remainder (7%) identify with smaller movements (such as Reconstructionism or the Jewish Renewal movement), say they belong to more than one movement (such as both Conservative and Orthodox), or decline to answer the question.

Most Jews by religion identify with either Reform (40%), Conservative (22%) or Orthodox Judaism (12%), with just 19% saying they belong to no particular denomination. By contrast, most Jews of no religion have no denominational affiliation (66%). However, one-in-five Jews of no religion describe themselves as Reform Jews (20%), while 6% identify with Conservative Judaism and 1% say they are Orthodox Jews.

Not all Jews who identify with a denominational movement or stream are members of synagogues. Among Jews who say they are synagogue members, 39% identify with Reform Judaism, 29% with Conservative Judaism, 22% with Orthodox Judaism, 4% with another denominational movement and 6% with no denomination.

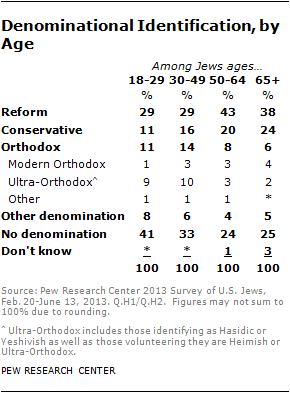

Compared with older Jews, younger Jews are more likely to have no denominational attachment and somewhat more likely to be Orthodox Jews. Four-in-ten Jewish adults under age 30 (41%) have no denominational affiliation, and 33% of Jews in their 30s and 40s have no denominational attachment. By contrast, only about a quarter of Jews 50 and older say they have no denominational affiliation.

Compared with older Jews, younger Jews are more likely to have no denominational attachment and somewhat more likely to be Orthodox Jews. Four-in-ten Jewish adults under age 30 (41%) have no denominational affiliation, and 33% of Jews in their 30s and 40s have no denominational attachment. By contrast, only about a quarter of Jews 50 and older say they have no denominational affiliation.

Among Jews under age 30, 11% are Orthodox Jews (including 9% who are Ultra-Orthodox). And among Jews in their 30s and 40s, 14% are Orthodox (including 10% who are Ultra-Orthodox). One-in-ten or fewer Jews ages 50 and older describe themselves as Orthodox Jews.

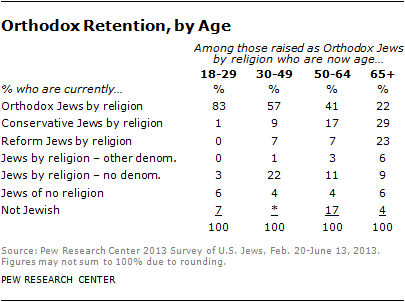

Though Orthodox Jews today make up 10% of the net Jewish population and 12% of current Jews by religion, larger numbers (14% of all Jews and 17% of Jews by religion) say they were raised as Orthodox. This reflects a high rate of attrition from Orthodox Judaism, especially among older cohorts. Among those 65 and older who were raised as Orthodox Jews, just 22% are still Orthodox Jews by religion. And among those ages 50-64 who were raised Orthodox, just 41% are still Orthodox Jews by religion. In stark contrast, 83% of Jewish adults under 30 who were raised Orthodox are still Orthodox. Some experts think this is not a result of accumulated departures as people get older (i.e., a life cycle effect), but rather could be a period effect in which people who came of age during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s left Orthodoxy in large numbers.

Though Orthodox Jews today make up 10% of the net Jewish population and 12% of current Jews by religion, larger numbers (14% of all Jews and 17% of Jews by religion) say they were raised as Orthodox. This reflects a high rate of attrition from Orthodox Judaism, especially among older cohorts. Among those 65 and older who were raised as Orthodox Jews, just 22% are still Orthodox Jews by religion. And among those ages 50-64 who were raised Orthodox, just 41% are still Orthodox Jews by religion. In stark contrast, 83% of Jewish adults under 30 who were raised Orthodox are still Orthodox. Some experts think this is not a result of accumulated departures as people get older (i.e., a life cycle effect), but rather could be a period effect in which people who came of age during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s left Orthodoxy in large numbers.

Importance of Being Jewish

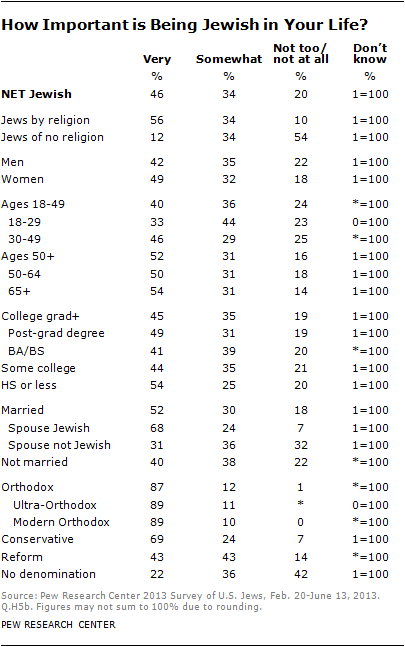

More than four-in-ten U.S. Jews (46%) say being Jewish is a very important part of their lives, and a third (34%) say being Jewish is somewhat important to them. One-fifth of Jews say that being Jewish is not too (15%) or not at all important to them (5%). Jews by religion are nearly five times more likely to say being Jewish is very important to them compared with Jews of no religion (56% vs. 12%).

More than four-in-ten U.S. Jews (46%) say being Jewish is a very important part of their lives, and a third (34%) say being Jewish is somewhat important to them. One-fifth of Jews say that being Jewish is not too (15%) or not at all important to them (5%). Jews by religion are nearly five times more likely to say being Jewish is very important to them compared with Jews of no religion (56% vs. 12%).

Nearly nine-in-ten Orthodox Jews (87%) and two-thirds of Conservative Jews (69%) describe being Jewish as very important in their lives. Far fewer self-identified Reform Jews say being Jewish is very important to them (43%). Among Jews who are unaffiliated with any particular Jewish movement or denomination, just one-in-five say being Jewish is very important to them (22%).

A third of Jews under age 30 say being Jewish is very important to them. Jewish identity is very important to larger numbers of older Jews, including 46% of those ages 30-49, 50% of those ages 50-64 and 54% of those 65 and older.

Pride, Connectedness and Responsibility

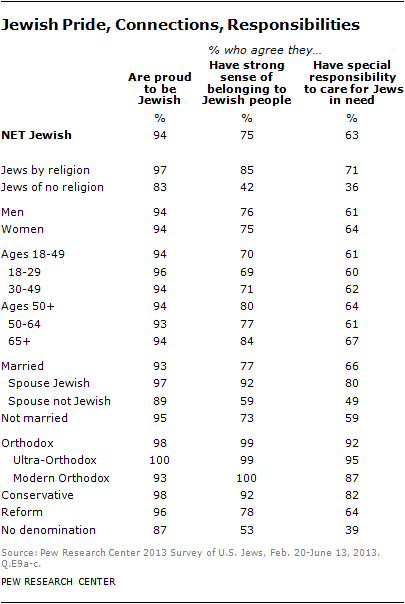

More than nine-in-ten Jews (94%) agree they are “proud to be Jewish.” Three-quarters (75%) say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, and about six-in-ten (63%) say they have a special responsibility to care for Jews in need around the world.

More than nine-in-ten Jews (94%) agree they are “proud to be Jewish.” Three-quarters (75%) say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, and about six-in-ten (63%) say they have a special responsibility to care for Jews in need around the world.

Overwhelming majorities of both Jews by religion and Jews of no religion say they are proud to be Jewish (97% and 83%, respectively). Most Jews by religion also say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people (85%) and that they feel a responsibility to care for Jews in need (71%). Far fewer Jews of no religion share these sentiments.

Large majorities in all of the major Jewish movements express pride in being Jewish. Virtually all Orthodox (99%) and nine-in-ten Conservative Jews (92%) feel a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, as do 78% of Reform Jews. This connection with the Jewish people is felt less strongly by those with no denominational attachment (53%). Similarly, while majorities of Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Jews say they have a special responsibility to care for Jews in need, less than half of Jews with no denominational affiliation (39%) feel this kind of responsibility.

More older Jews than younger Jews say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people. Eight-in-ten Jews 50 and older (80%) say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people, compared with 70% of Jews under age 50. Differences among the age groups are smaller on the questions about pride in being Jewish and caring for Jews in need.

Married Jews who have Jewish spouses feel more connected to and responsible for other Jews as compared with Jews who are married to non-Jews. Fully nine-in-ten Jews married to fellow Jews say they have a strong sense of belonging to the Jewish people (92%), and 80% say they feel a responsibility to care for Jews in need. The comparable figures for Jews in mixed marriages are 59% and 49%, respectively.

What Does it Mean to be Jewish?

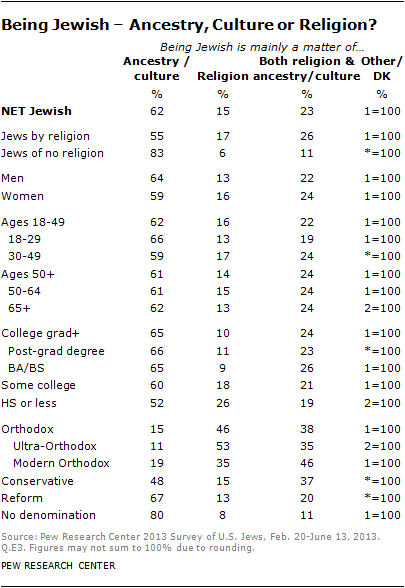

When asked whether being Jewish is mainly a matter of religion, ancestry or culture, six-in-ten (62%) cite either ancestry or culture (or a combination of the two). Fewer than one-in-five (15%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of religion. About a quarter of Jews (23%) say being Jewish is a matter of religion as well as ancestry and/or culture.

More than half of Jews by religion (55%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry or culture, while 17% say it is mainly a matter of religion, and 26% say it is a combination of religion and ancestry/culture. Roughly eight-in-ten Jews of no religion (83%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry or culture, while just 6% say it is mainly a matter of religion.

More than half of Jews by religion (55%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry or culture, while 17% say it is mainly a matter of religion, and 26% say it is a combination of religion and ancestry/culture. Roughly eight-in-ten Jews of no religion (83%) say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry or culture, while just 6% say it is mainly a matter of religion.

Orthodox Jews are more apt than other Jews to say that being Jewish is mainly a matter of religion. But even among the Orthodox, large numbers say being Jewish is mainly a matter of ancestry and culture (15%) or that being Jewish is a matter of both religion and ancestry/culture (38%).

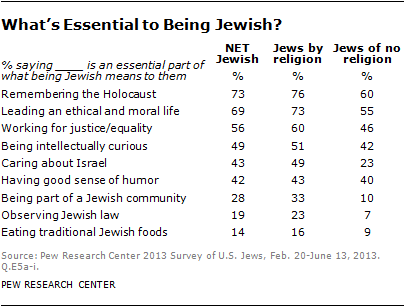

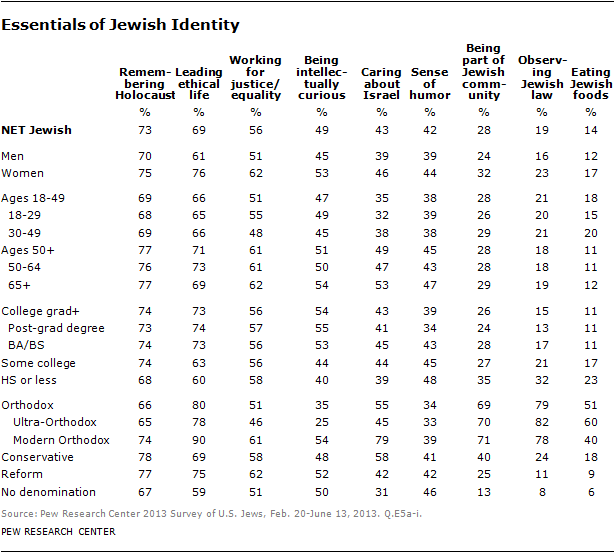

The survey asked Jews whether each of nine attributes and activities is essential to what being Jewish means to them, is important but not essential, or is not an important part of what it means to be Jewish. In response, roughly seven-in-ten U.S. Jews (73%) say remembering the Holocaust is an essential part of what being Jewish means to them. Nearly as many say leading an ethical and moral life is essential to what it means to be Jewish. And a majority of U.S. Jews say working for justice and equality in society is essential to being Jewish.

Nearly half of U.S. Jews (49%) say being intellectually curious is central to their Jewish identity, and four-in-ten also include caring about Israel (43%) and having a good sense of humor (42%) as essential to what it means to be Jewish. Fewer Jews cite being part of a Jewish community (28%), observing Jewish law (19%) and eating traditional Jewish foods (14%) as essential elements of their Jewish identity.

Nearly half of U.S. Jews (49%) say being intellectually curious is central to their Jewish identity, and four-in-ten also include caring about Israel (43%) and having a good sense of humor (42%) as essential to what it means to be Jewish. Fewer Jews cite being part of a Jewish community (28%), observing Jewish law (19%) and eating traditional Jewish foods (14%) as essential elements of their Jewish identity.

Across the board, Jews by religion are more likely than Jews of no religion to consider the nine attributes or activities as essential to being Jewish. Both groups, however, prioritize the items in a similar way. Remembering the Holocaust and leading an ethical and moral life are most frequently cited as essential by both Jews by religion and Jews of no religion. And both groups rank observing Jewish law and eating traditional Jewish foods near the bottom of what it means to be Jewish.

However, one striking difference between the two groups is the importance they attach to caring about Israel. About half of Jews by religion (49%) say caring about Israel is essential to what it means to them to be Jewish. Among Jews of no religion, by contrast, roughly a quarter express this view (23%). In fact, Jews of no religion are more likely to see having a good sense of humor as essential to what it means to be Jewish than to see caring about Israel as essential to their Jewish identity (40% vs. 23%).

The survey also finds a generational divide in the importance attached to caring about Israel. Among Jews 65 and older, about half (53%) say caring about Israel is essential to what being Jewish means to them. Among Jews under age 30, by contrast, 32% express this view. Older Jews also are more likely than their younger counterparts to say remembering the Holocaust, working for justice and equality in society, and having a good sense of humor are essential to their Jewish identity.

The view that remembering the Holocaust is essential to what it means to be Jewish is shared by majorities in all of the large Jewish denominational groupings. But there are sizable differences across denominations in the importance attached to Israel. Half or more of Conservative Jews (58%) and Orthodox Jews (55%) say caring about Israel is essential to what being Jewish means to them. Among Reform Jews, 42% express this view. And among Jews with no denominational affiliation, just 31% say caring about Israel is essential to their Jewish identity.

Eight-in-ten Orthodox Jews (79%) say observing Jewish law is essential to what being Jewish means to them. This view is shared by just 24% of Conservative Jews, 11% of Reform Jews and 8% of Jews with no denominational affiliation.

What is Compatible – and What is Incompatible – With Being Jewish?

American Jews overwhelmingly say a person can be Jewish even if they work on the Sabbath (94%) or are strongly critical of Israel (89%). Two-thirds (68%) also say a person can be Jewish even if they do not believe in God. Far fewer say believing that Jesus was the messiah is compatible with being Jewish. Even here, however, a sizable minority (34%) says a person can be Jewish even if he or she believes Jesus was the messiah.

American Jews overwhelmingly say a person can be Jewish even if they work on the Sabbath (94%) or are strongly critical of Israel (89%). Two-thirds (68%) also say a person can be Jewish even if they do not believe in God. Far fewer say believing that Jesus was the messiah is compatible with being Jewish. Even here, however, a sizable minority (34%) says a person can be Jewish even if he or she believes Jesus was the messiah.

Among both Jews by religion and Jews of no religion, roughly nine-in-ten or more say a person can be Jewish even if they work on the Sabbath or are strongly critical of Israel. Jews of no religion are somewhat more inclined than Jews by religion to say a person can be Jewish even if he or she does not believe in God (75% vs. 66%). Similarly, Jews of no religion are more likely than Jews by religion to say believing in Jesus is compatible with being Jewish (47% vs. 30%).

Among both Jews by religion and Jews of no religion, roughly nine-in-ten or more say a person can be Jewish even if they work on the Sabbath or are strongly critical of Israel. Jews of no religion are somewhat more inclined than Jews by religion to say a person can be Jewish even if he or she does not believe in God (75% vs. 66%). Similarly, Jews of no religion are more likely than Jews by religion to say believing in Jesus is compatible with being Jewish (47% vs. 30%).

Jewish college graduates are nearly unanimous in saying a person can be Jewish even if they work on the Sabbath (98%), and three-quarters say a person can be Jewish without believing in God (73%). These views are shared by smaller majorities of Jews with less education. On the question of whether believing in Jesus is compatible with being Jewish, however, those who have not graduated from college are more permissive than Jewish college graduates; 48% of Jews with a high school diploma or less education and 38% of those with some college say a person can be Jewish even if they believe Jesus was the messiah, compared with 28% among college graduates.

The view that a person can be Jewish even if they work on the Sabbath is shared by a large majority of Orthodox Jews (75%). And nearly six-in-ten Orthodox Jews say a person can be Jewish without believing in God (57%). There are, however, large differences between Modern Orthodox Jews and Ultra-Orthodox Jews on these questions, with Ultra-Orthodox Jews espousing a stricter standard about what is compatible with being a Jew. Whereas 96% of Modern Orthodox say a person can be Jewish and work on the Sabbath, far fewer Ultra-Orthodox Jews share this view (64%). And while seven-in-ten Modern Orthodox (70%) say a person can be Jewish without believing in God, just half of Ultra-Orthodox say the same (50%).

Participation in Jewish Causes and Organizations

Roughly one-third of Jews (31%) say they belong to a synagogue, and nearly one-in-five (18%) say they belong to other kinds of Jewish organizations. A majority of Jews (56%) say they made a donation to a Jewish charity or cause in 2012.

Roughly one-third of Jews (31%) say they belong to a synagogue, and nearly one-in-five (18%) say they belong to other kinds of Jewish organizations. A majority of Jews (56%) say they made a donation to a Jewish charity or cause in 2012.

Participating in Jewish organizations in these ways is far more common among Jews by religion than among Jews of no religion. Synagogue membership is nearly 10 times more common among Jews by religion than among Jews of no religion (39% vs. 4%), and membership in other Jewish organizations is almost six times more common among Jews by religion than Jews of no religion (22% vs. 4%). And while 67% of Jews by religion say they made a donation to a Jewish cause in 2012, just 20% of Jews of no religion say the same.

Having made a financial contribution to a Jewish cause is more common among older Jews than among younger Jews. Making financial donations to Jewish causes is also more common among people in high-income households than among those with lower household incomes. Nearly two-thirds of Jews with a household income of $150,000 or more say they made a donation to a Jewish cause in 2012, as do 60% of those with incomes between $100,000 and $150,000 and 54% of those earning between $50,000 and $100,000. Among those earning less than $50,000, 46% say they donated to a Jewish cause. Higher household income also is associated with higher rates of synagogue membership. But the link between income and membership in other kinds of Jewish organizations is weaker.

Compared with members of other denominations, more Orthodox Jews say they belong to Jewish organizations and donate to Jewish causes. Perhaps not surprisingly, relatively few Jews who have no denominational affiliation say they belong to a synagogue (6%) or other Jewish organizations (4%).

Among married Jews, those who have Jewish spouses are much more engaged in the Jewish community in these ways than are those married to non-Jews. Nearly nine-in-ten Jews married to a Jewish spouse (88%) say they donated to a Jewish cause last year, compared with 42% of Jews in mixed marriages. Almost six-in-ten Jews married to a Jewish spouse (59%) say they belong to a synagogue, roughly four times the rate seen among Jews in mixed marriages (14%). And whereas one-third of Jews who are married to a Jewish spouse say they belong to a Jewish organization other than a synagogue, just 6% of those married to a non-Jew say the same.

Jewish Friendship Networks

About a third of American Jews say that all (5%) or most (27%) of their close friends are Jewish. By comparison, 57% of Mormons say all (4%) or most (53%) of their close friends are Mormon, and about half of U.S. Muslims say that all (7%) or most (41%) of their friends are Muslim.23

About a third of American Jews say that all (5%) or most (27%) of their close friends are Jewish. By comparison, 57% of Mormons say all (4%) or most (53%) of their close friends are Mormon, and about half of U.S. Muslims say that all (7%) or most (41%) of their friends are Muslim.23

Jews by religion are far more likely than Jews of no religion to say that most or all of their close friends are Jewish (38% vs. 14%). Among Orthodox Jews, 84% have a close circle of friends consisting mostly or entirely of other Jews, compared with 39% of Conservative Jews and 28% of Reform Jews. Among Jews with no denominational affiliation, 17% say all or most of their close friends are Jewish.

Older Jews are more connected with Jewish social networks than are younger Jews; 44% of those 65 and older say all or most of their friends are Jewish, while far fewer of those ages 18-29 (25%), 30-49 (32%) and 50-64 (30%) say the same about their close circle of friends.

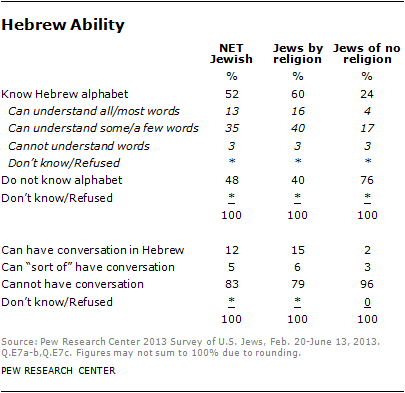

Hebrew Language Ability

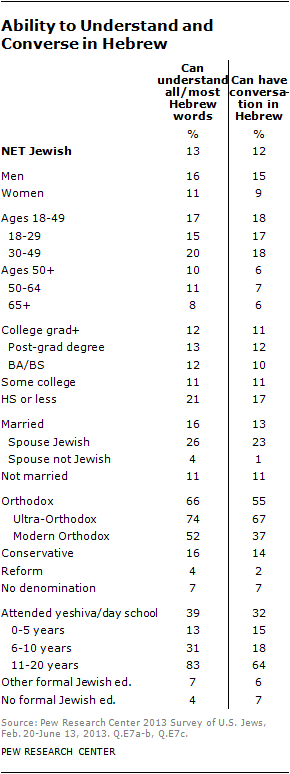

Fully half of U.S. Jews (52%) say they know the Hebrew alphabet, though far fewer (13%) say they can understand most or all of the words when they read Hebrew. Roughly one-in-ten Jews say they can carry on a conversation in Hebrew, with an additional 5% volunteering they can “sort of” have a conversation in Hebrew.

Fully half of U.S. Jews (52%) say they know the Hebrew alphabet, though far fewer (13%) say they can understand most or all of the words when they read Hebrew. Roughly one-in-ten Jews say they can carry on a conversation in Hebrew, with an additional 5% volunteering they can “sort of” have a conversation in Hebrew.

Facility with Hebrew is much more common among Jews by religion than among Jews of no religion. Six-in-ten Jews by religion say they know the Hebrew alphabet (60%), compared with 24% of Jews of no religion. And whereas 15% of Jews by religion say they can have a conversation in Hebrew, just 2% of Jews of no religion say the same.

Proficiency with Hebrew is much more common among Orthodox Jews – especially the Ultra-Orthodox – than among members of other Jewish denominations. Two-thirds of Orthodox Jews (and 74% of the Ultra-Orthodox) say they can understand all or most of the words when reading Hebrew, and 55% of Orthodox Jews (including 67% of Ultra-Orthodox Jews) say they can carry on a conversation in Hebrew.

Proficiency with Hebrew is much more common among Orthodox Jews – especially the Ultra-Orthodox – than among members of other Jewish denominations. Two-thirds of Orthodox Jews (and 74% of the Ultra-Orthodox) say they can understand all or most of the words when reading Hebrew, and 55% of Orthodox Jews (including 67% of Ultra-Orthodox Jews) say they can carry on a conversation in Hebrew.

Jews with a high school degree or less education report being able to understand written Hebrew at somewhat higher rates than do Jews with college experience.

Hebrew proficiency is higher among Jews who attended a yeshiva or Jewish day school than among Jews who had some other sort of formal Jewish education only. Four-in-ten (39%) of those who attended Jewish day school or yeshiva report being able to understand all or most Hebrew words, and a third (32%) say they can have a conversation in Hebrew. Proficiency rates increase with the number of years spent in formal schooling; 83% of those who attended yeshiva or a Jewish day school for more than 10 years can understand all or most Hebrew words, and 64% of that group can hold a conversation in Hebrew. Fewer than one-in-ten Jews who had some other formal Jewish education only (other than yeshiva or day school) can understand all or most Hebrew words (7%) or carry on a conversation in Hebrew (6%).

Adults’ Upbringing and Education

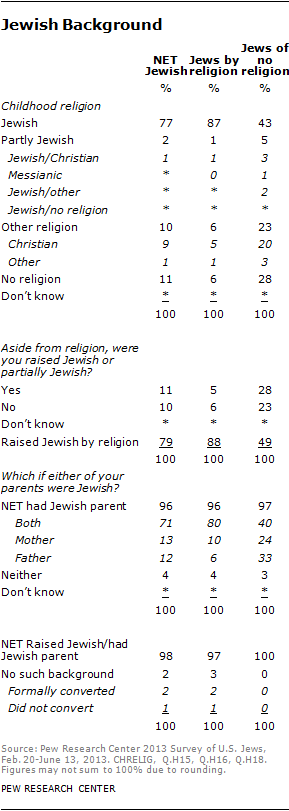

Three-quarters of Jews say they were raised Jewish by religion (77%). One-in-ten (11%) say they were not raised Jewish by religion but were raised Jewish aside from religion (e.g., culturally, ethnically or secularly Jewish). Nearly nine-in-ten Jews by religion say they were raised Jewish by religion, and 5% say they were raised Jewish aside from religion. Almost half of Jews of no religion were raised Jewish or partially Jewish by religion, with 28% saying they were raised Jewish aside from religion.

Nearly all Jews say they had at least one Jewish parent, including 96% of Jews by religion and 97% of Jews of no religion.

All in all, 98% of Jews (and, by definition, 100% of Jews of no religion) were raised Jewish or had at least one Jewish parent; 2% of Jews had no such background but indicate they had a formal conversion to Judaism, while 1% did not formally convert.

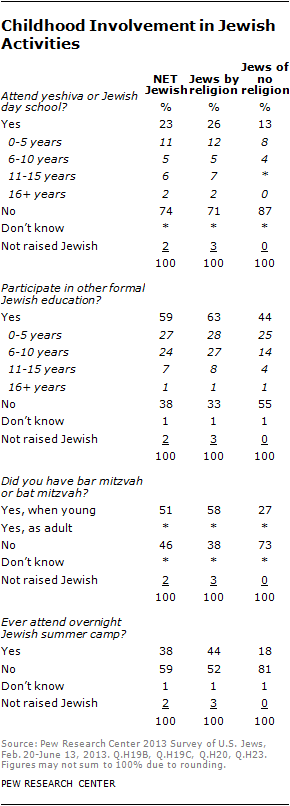

Nearly one-quarter of Jews (23%) say they attended a yeshiva or Jewish day school as a child. And nearly six-in-ten say they participated in other formal Jewish education programs aside from day school. Overall, 67% of Jews either attended a Jewish day school or participated in some other kind of formal Jewish education.

Jews by religion are more likely to have participated in these kinds of programs than are Jews of no religion. But even among Jews of no religion, sizable minorities say they attended yeshiva or day school (13%) or some other kind of Jewish educational program (44%).

Roughly half of Jews (51%) say they have had a bar mitzvah or a bat mitzvah. Most Jews by religion have undergone this rite of passage (58%), whereas about one-quarter of Jews of no religion have had a bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah.

More than one-third of Jews say they attended an overnight Jewish summer camp as a child, including 44% of Jews by religion who say they had this experience. Fewer Jews of no religion (18%) say they spent time at an overnight Jewish summer camp.

Child Rearing

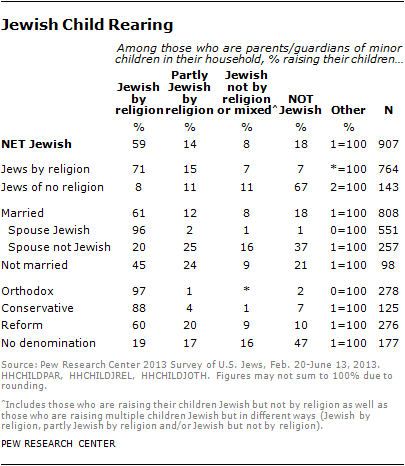

Among Jews who are currently parents or guardians of at least one child residing in their household, about eight-in-ten say they are raising those children as Jewish. This includes 59% who say they are raising their children Jewish by religion, 14% who say they are raising their children partly Jewish by religion and partly something else, and 8% who are raising their children Jewish but not by religion or who have multiple children with some being raised Jewish by religion and others being raised partially Jewish. Roughly one-in-five (18%) say they are not raising their children Jewish at all.

Among Jews who are currently parents or guardians of at least one child residing in their household, about eight-in-ten say they are raising those children as Jewish. This includes 59% who say they are raising their children Jewish by religion, 14% who say they are raising their children partly Jewish by religion and partly something else, and 8% who are raising their children Jewish but not by religion or who have multiple children with some being raised Jewish by religion and others being raised partially Jewish. Roughly one-in-five (18%) say they are not raising their children Jewish at all.

Among parents of minor children, more than nine-in-ten Jews by religion say they are raising their children Jewish in some way; 71% are raising their children Jewish by religion, 15% partly Jewish by religion and 7% Jewish but not by religion. Among Jews of no religion, by contrast, two-thirds (67%) say they are not raising their children Jewish in any way.

Among Jews in the largest denominational movements – Reform, Conservative and Orthodox – roughly nine-in-ten or more say they are raising their children Jewish. This includes 97% of Orthodox Jews and 88% of Conservative Jews who are raising their children Jewish by religion. But nearly half of Jewish parents who have no denominational affiliation (47%) say they are not raising their children Jewish (either by religion or otherwise).

There are vast differences in the approaches to child rearing by Jewish parents who are married to a Jewish spouse compared with Jewish respondents married to a non-Jewish spouse. Among the former group, 96% say they are raising their children Jewish by religion, and just 1% say they are not raising their children Jewish. But among Jews married to non-Jews, just 20% say they are raising their children Jewish by religion, and 37% say their children are not being raised Jewish.

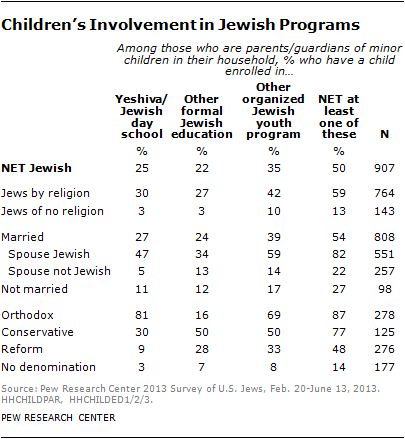

Overall, 25% of Jewish parents say they have a child who was enrolled in a yeshiva or Jewish day school in the past year; 22% say they have a child who was enrolled in some other kind of Jewish educational program, and 35% say they have a child enrolled in other kinds of Jewish youth programs such as Jewish day care, youth groups, day camps and sleep-away camps. In total, 50% of Jewish parents say they had a child enrolled in at least one of these kinds of programs over the past year.24

Overall, 25% of Jewish parents say they have a child who was enrolled in a yeshiva or Jewish day school in the past year; 22% say they have a child who was enrolled in some other kind of Jewish educational program, and 35% say they have a child enrolled in other kinds of Jewish youth programs such as Jewish day care, youth groups, day camps and sleep-away camps. In total, 50% of Jewish parents say they had a child enrolled in at least one of these kinds of programs over the past year.24

Participation by their children in all of these types of activities is far more common among parents who are Jews by religion than among Jews of no religion. Nearly six-in-ten Jews by religion (59%) had a child participating in at least one of these kinds of programs, compared with 13% of Jews of no religion. Similarly, Jewish parents who are married to a Jewish spouse are roughly four times as likely to have enrolled their children in one of these types of programs compared with Jews who are married to non-Jews (82% vs. 22%).

Among Orthodox Jewish parents, 87% say they have at least one child enrolled in at least one of the youth programs asked about in the survey, including 81% who say they have a child enrolled in a yeshiva or Jewish day school. Three-quarters of Conservative Jewish parents (77%) say they have a child enrolled in at least one of these activities, as do roughly half of Reform Jewish parents (48%). Among Jewish parents who have no denominational affiliation, 14% have a child enrolled in a Jewish educational or youth program.