The share of the world’s countries with high or very high restrictions on religion has increased significantly in recent years, as documented in this study and previous Pew Research Center reports.1 Governments and societies around the world have attempted to address the rising tide of restrictions through a variety of initiatives and actions, from encouraging interfaith dialogue to modifying laws and policies.

As an extension of its continuing research on restrictions on religion around the world, Pew Research counted and categorized (“coded”) reports of these types of initiatives during calendar year 2011.2 The coding relied on widely cited, publicly available sources from groups such as the U.S. State Department, the United Nations, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and the International Crisis Group. (For a full list of sources, see Information Sources in the Methodology.)

The initiatives and actions were grouped into four broad categories: (1) interfaith dialogue; (2) efforts to combat or redress religious discrimination; (3) educational and training initiatives; and (4) land- or property-related initiatives (including the granting of building permits to construct or expand worship facilities).

This supplementary analysis has some important limitations. First, the coding does not attempt to assess the effectiveness of particular initiatives. Gauging effectiveness is difficult, in part because some initiatives may take years to produce results while others may have a short-term impact but little or no effect over the longer term.

Second, the sources used in this study tend to focus on the actions of governments more than the actions of nongovernmental organizations or other groups in society. Therefore, this supplementary analysis likely conveys a more complete picture of initiatives by governments than by private individuals or groups.

Finally, the Pew Research Center’s coding is meant to be values-neutral. The statement that a country had an initiative to reduce religious restrictions or hostilities is not intended to extol countries with such initiatives or to condemn those without such initiatives. The coding does not involve assigning credit or blame.

Key Findings

Analysis of data from calendar year 2011 finds that government or societal initiatives to reduce religious restrictions or hostilities were reported in 150 of 198 countries, or 76% of all the countries and territories studied. The most common types of initiatives, in descending order of prevalence, were: interfaith dialogue; efforts to combat or redress religious discrimination; educational and training initiatives; and land- or property-related initiatives.

Interfaith Dialogue

In 2011, interfaith-dialogue initiatives occurred in 110 of the 198 countries (56%), according to the sources used in this study.

Some of these efforts focused primarily on fostering communication and cooperation among leaders of religious groups. In Bolivia, for instance, leaders of the Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, Jewish and indigenous communities continued to hold interfaith meetings in 2011. For the first time, a representative of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also regularly participated in the sessions.3

Other interfaith-dialogue projects involved people-to-people contact. In November 2011, for instance, UNICEF and the Global Network for the Religion of Children, an interfaith children’s rights group, brought together more than 2,000 children of diverse religious backgrounds from the Tanzanian mainland and Zanzibar. The children participated in joint prayer sessions and attended music, drama and poetry events.4

The purpose of some interfaith dialogues was to develop strategies to combat religious intolerance. In May 2011, for example, 80 Muslim and Jewish leaders from Ukraine and Russia met in Kiev to work on a strategy to fight anti-Semitism and discrimination against Muslims.5 In 2011, the government of Paraguay established a permanent interfaith forum to promote dialogue between various religions.6

Governments sometimes encouraged interfaith dialogue as a strategy to reduce tensions between religious groups. For instance, the Liberian government encouraged Muslim-Christian dialogue in 2011 after mosques, churches and a Catholic school were damaged the previous year during religious violence in the northernmost part of the country.7

Some initiatives involved multiple countries. For instance, the governments of Saudi Arabia, Austria and Spain signed an agreement to establish the King Abdullah International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICIID) in October 2011. The center was inaugurated about a year later in Vienna, Austria, with the mission of fostering dialogue among members of different religions and cultures around the world.8

Efforts to Combat or Redress Religious Discrimination

Efforts to combat or redress religious discrimination and increase tolerance were reported in a total of 76 countries (38%) in 2011. These included changes to basic laws; establishment of government mechanisms to address religious tensions or grievances; official recognition of religious groups that previously found themselves in legal limbo; freeing prisoners held for religious reasons; protecting those in danger of persecution; and partnering with groups in society to address religious hatred and prejudice, among other initiatives.

In December 2011, for instance, the Mexican Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Mexican legislature, took steps to amend Article 24 of the Constitution to allow public celebrations of religious events without first obtaining government permission.9 (The proposal was approved by the Senate in March 2012. At least 17 of Mexico’s 31 states need to approve it for the proposal to become law. As of May 2013, more than a dozen states had submitted their approval to the Senate.10) In Jordan, an amended Public Gatherings Law took effect in March 2011, making it no longer necessary to obtain government permission for public meetings or demonstrations, including religious events.11

Some countries established government mechanisms to address religious tensions. The Austrian government, for example, appointed its first state secretary for integration in April 2011. The secretary is responsible for coordinating the government’s efforts to promote integration among the country’s ethnic and religious minorities, including Austria’s large ethnic Turkish community.12 In Canada, the Conservative Party – which won a majority of seats in Parliament in the 2011 elections – included in its platform a commitment to open an office within the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade to address religious freedom and tolerance.13 (The Canadian government officially opened the new Office of Religious Freedom in February 2013.14)

Several initiatives sought to address immigration restrictions that adversely affected religious groups. For instance, changes to New Zealand’s immigration policy made it easier for religious groups to recruit and retain workers from abroad by allowing for longer temporary visas that give workers more time to apply for permanent residency.15 And the Dutch government announced in September 2011 that it would no longer require Turkish migrants to pass a civic integration exam before immigrating to the Netherlands.16

Other policy changes included government recognition of previously unrecognized religious groups. For instance, the Azerbaijani government officially registered the Roman Catholic Church in July 2011.17 In September 2011, the Albanian government recognized Judaism as an official religion.18 And in October 2011, the Spanish government approved a process allowing 300 Muslim organizations to affiliate with the state-recognized Islamic Commission of Spain. Affiliation with the commission comes with certain benefits, including nonprofit tax status.19

In addition, some governments allowed religious groups to operate more freely in 2011 than in previous years. For instance, the Catholic Church was permitted to expand pastoral services to more regions in Laos and Vietnam.20 And in Cuba, the government allowed churches to broadcast limited religious programming on state-run radio and TV stations. There also were fewer reports of Cuban house churches being harassed in 2011, according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom.21

Governments in a number of countries released prisoners being held for religious activities or affiliations. In Uzbekistan, for instance, approximately 20 prisoners were reportedly released in the city of Andijan during 2011.22 In Morocco, the king pardoned more than 2,800 prisoners during the year, including 190 Salafists who had been held since a terrorist bombing incident in Casablanca in 2003.23 In May 2011, Sri Lankan authorities released Sarah Malanie Perera, who had been arrested in April 2010 under the Prevention of Terrorism Act because of a book she wrote describing her conversion from Buddhism to Islam.24

There also were initiatives to better protect the religious rights of incarcerated individuals. For instance, Chile’s Ministry of Justice began providing inmates with additional access to religious support services in 2011.25

A number of governments tried to protect those in danger of religious persecution. For instance, in July 2011, the Seoul Administrative Court – in what was described as an unprecedented reversal of a Ministry of Justice decision – granted refugee status to three Iranian Muslims who had converted to Christianity while living in South Korea.26 If deported to Iran, they could have faced apostasy charges, carrying a possible death sentence.27

Some government initiatives focused on protecting individuals accused of witchcraft from societal abuse. For instance, Burkina Faso’s government and tribal authorities worked together in 2011 on an awareness program and assisted with mediation efforts between local elders and accused witches.28 Similar efforts to resolve accusations of witchcraft were carried out by Ghana’s Ministry of Women and Children in 2011.29

Other initiatives sought to prevent violence against religious minorities. The government of Bangladesh, for instance, increased security deployments in 2011 to ensure the peaceful celebration of Hindu, Christian and Buddhist festivals.30

Educational and Training Initiatives

According to the sources coded for this analysis, in addition to interfaith dialogues, other educational and training initiatives to increase religious tolerance and decrease religious tensions occurred in a total of 39 countries (20%) in 2011.

Some educational and training programs were aimed at the general public. For instance, for five days each week in 2011, Portuguese state television aired a 30-minute program with segments written by various religious communities in the country; the segments were designed to encourage tolerance for religious diversity.31

Other educational programs targeted schools and teachers. Norway’s federal minister of education pledged six million kroner (about $1 million) in 2011 to train teachers to combat anti-Semitism in schools.32 Also in 2011, the Ministry of Education in Cyprus ran seminars on religious diversity for school teachers.33

In some cases, educational projects targeted groups considered susceptible to extremism. For instance, following 2010 terrorist attacks in Uganda, police in the country increased their outreach to local Muslim youth considered at-risk for recruitment by violent extremist groups.34

Other projects targeted research and university communities. The government of Oman, for instance, supported an endowed professorship of Abrahamic faiths at Cambridge University and sponsored 10 Omani students to participate in a religious pluralism program at the university.35

Several educational projects focused on helping religious communities and government officials better understand how to work within the law. One such project was carried out in Laos by the Institute for Global Engagement (a U.S.-based organization) in collaboration with the Lao Front for National Construction (the national agency responsible for religious affairs, among other issues). The training program helped local government officials and religious leaders not only to better relate to one another but also to better understand the Laotian basic law on religion (Decree 92).36

Some programs focused specifically on religious training. In Morocco, for instance, the government continued a training program begun in 2006 to increase women’s participation in Muslim religious life. According to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, the government stated that the training the women receive “is exactly the same as that required of male imams.”37

Training initiatives also can involve multiple countries. For instance, at the invitation of U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, representatives of 26 governments and four international organizations convened in Washington, D.C., from Dec. 12-14, 2011, to discuss the implementation of United Nations Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18 on combating religious intolerance and discrimination.38 A central focus of the meeting was on training government officials in effective outreach to religious communities.39

Land- or Property-Related Initiatives

In 2011, governments or groups in society intervened in a total of 29 countries (15%) on behalf of religious groups that previously had experienced problems acquiring land or obtaining building permits.

The Kuwaiti government, for instance, gave the Coptic Orthodox Church a parcel of land on which to construct a worship facility for its thousands of members in the country; the facility was nearing completion at the end of 2011.40 Also in 2011, the Greek government provided worship space for Athens’ Muslim community, unlike during the previous year.41

In Denmark, after a vigorous public debate on whether mosques with domes and minarets should be permitted in the country, the Copenhagen city council approved plans for the construction of two major mosques. Commenting on this, Copenhagen Employment and Integration Mayor Anna Mee Allerslev stated, “We have freedom of religion and free speech in Denmark, and therefore it is quite natural to have two beautiful mosques in Copenhagen.”42

Religious groups in some countries were able to rebuild properties that previously had been destroyed during religion-related violence. In September 2011, for instance, the Serbian Orthodox Church’s seminary reopened in Prizren, Kosovo. The seminary building was evacuated in 1999 due to security concerns and later destroyed during riots in 2004.43 In Kashmir, India, Muslims rebuilt a Christian school destroyed during religion-related violence in 2010.44

Some governments took steps to restore religious properties seized in previous decades. For instance, in June 2011, the Lithuanian Parliament passed a law mandating compensation to the Jewish community for properties taken during the Holocaust.45 And in August 2011, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced a new policy allowing non-Muslim communities to apply for compensation or return of properties confiscated by the state in 1936.46

Regions

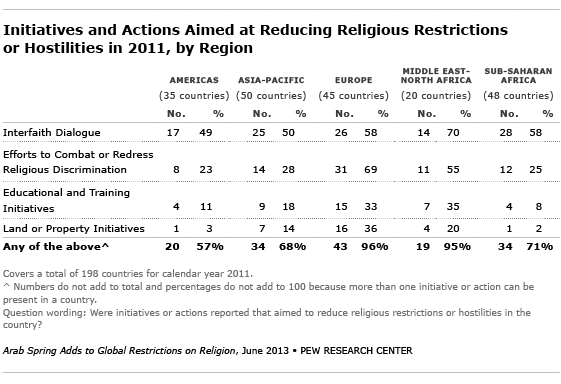

Initiatives and actions aimed at reducing religious restrictions or hostilities occurred in every region of the world in 2011. (See table below.) According to the sources coded for this analysis, these initiatives and actions were present in 96% of countries in Europe (43 of 45 countries) and 95% of countries in the Middle East and North Africa (19 of 20). Such initiatives and actions also were present in 71% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa (34 of 48), 68% of countries in the Asia-Pacific region (34 of 50) and 57% of countries in the Americas (20 of 35).

In Europe, policies or actions to combat or redress discrimination outnumbered interfaith dialogue as the most common effort to reduce religious restrictions or hostilities. In each of the other regions, by contrast, the most common initiative or action was interfaith dialogue. Europe and the Middle East-North Africa region had larger shares of countries than the three other regions with educational and training initiatives as well as land and property initiatives aimed at reducing religious restrictions or hostilities.

Footnotes:

1 See the Pew Research Center’s September 2012 report “Rising Tide of Restrictions on Religion,” https://legacy.pewresearch.org/religion/Government/Rising-Tide-of-Restrictions-on-Religion.aspx. Also see the Pew Research Center’s August 2011 report “Rising Restrictions on Religion,” https://legacy.pewresearch.org/religion/Government/Rising-Restrictions-on-Religion.aspx. (return to text)

2 This is the first time the Pew Research Center has included a question on initiatives and actions to reduce religious restrictions or hostilities in its ongoing study of global restrictions on religion. For consistency’s sake, the results of this question are not included in the Government Restrictions Index (GRI) or the Social Hostilities Index (SHI). (return to text)

3 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Bolivia.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/wha/192953.htm. (return to text)

4 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Tanzania.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/af/192767.htm . (return to text)

5 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Ukraine.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192873.htm. (return to text)

6 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Paraguay.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/wha/192993.htm. (return to text)

7 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Liberia.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/af/192727.htm. (return to text)

8 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Saudi Arabia.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/nea/192905.htm. For differing perspectives on KAICIID, see Schneider, Marc. Dec. 3, 2012. “Amid Conflict, King Abdullah Interfaith Center Replaces Fear with Hope.” The Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rabbi-marc-schneier/king-abdullah-interfaith-center-replaces-fear-with-hope_b_2232101.html. Also see, Abrams, Elliot. Dec. 31, 2012. “Plotting to Celebrate Christmas.” Council on Foreign Relations. http://blogs.cfr.org/abrams/2012/12/31/plotting-to-celebrate-christmas/.(return to text)

9 Human Rights Without Frontiers International. 2011. “Mexico.” Freedom of Religion or Belief Newsletter. http://www.hrwf.net/images/forbnews/2011/mexico%202011.pdf.(return to text)

10 See Mexico Senate of the Republic. May 2, 2013. “Reforma Constitucional turnada a los Congresos Estatales.” http://www.senado.gob.mx/index.php?ver=sen&mn=9&sm=23; and “Punto de Acuerdo” submitted to the Tabasco State Congress Mexico Congress of the Union on Feb. 15, 2013. “Direccion de Estudios Legislativos.” http://tempo.congresotabasco.gob.mx/documentos/2013/LXI/Estudio%20Legislativo/PUNTOS%20DE%20ACUERDO/6.pdf. (return to text)

11 Human Rights Watch. January 2012. “Jordan.” World Report 2012. http://www.hrw.org/world-report-2012/world-report-2012-jordan. (return to text)

12 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Austria.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192783.htm. For more information on religion and migration, see the Pew Research Center’s March 2012 report “Faith on the Move: The Religious Affiliation of International Migrants,” https://legacy.pewresearch.org/religion/faith-on-the-move.aspx. (return to text)

13 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Canada.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192957. (return to text)

14 For more information, see the website for the Canadian Office of Religious Freedom. http://www.international.gc.ca/religious_freedom-liberte_de_religion/index.aspx. (return to text)

15 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “New Zealand.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eap/192651.htm. (return to text)

16 Under a law that took effect on Jan. 1, 2007, migrants to the Netherlands must demonstrate that they have a basic command of the Dutch language and a basic knowledge of Dutch society. Their knowledge is tested in a civic integration exam. See http://www.government.nl/issues/integration/civic-integration. Also see, Human Rights Watch. January 2012. “European Union.” World Report 2012. http://www.hrw.org/world-report-2012/world-report-2012-european-union. (return to text)

17 While the Azerbaijani government permitted the Roman Catholic Church to legally register in the country, the U.S. State Department’s 2011 International Religious Freedom report on Azerbaijan says that the registration process continued “to serve as a point of leverage for the government to use against religious groups it deems undesirable.” For more information on this issue, see U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Azerbaijan.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192785.htm. (return to text)

18 U.S. Department of State. May 24, 2012. “Albania.” 2011 Human Rights Report. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2011/eur/186322.htm. (return to text)

19 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Spain.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192865. (return to text)

20 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Laos.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2007/90142.htm. U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Vietnam.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192677. (return to text)

21 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Cuba.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192965. U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. March 2012. “Cuba.” 2012 Annual Report. http://www.uscirf.gov/images/Annual%20Report%20of%20USCIRF%202012(2).pdf. (return to text)

22 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Uzbekistan.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/sca/192941.htm. (return to text)

23 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Morocco.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192899. (return to text)

24 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Sri Lanka.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/sca/192935.htm. (return to text)

25 U.S. Department of State. May 24, 2012. “Chile.” 2011 Human Rights Report. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2011/wha/186499.htm.(return to text)

26 U.S. Department of State. May 24, 2012. “South Korea.” 2011 Human Rights Report. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?dlid=186282. (return to text)

27 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Iran.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/nea/192883.htm. (return to text)

28 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Burkina Faso.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192685. (return to text)

29 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Ghana.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192717. (return to text)

30 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Bangladesh.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/sca/192919.htm.(return to text)

31 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Portugal.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192851. (return to text)

32 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Norway.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192847.htm. (return to text)

33 U.S. Department of State. May 24, 2012. “Cyprus.” 2011 Human Rights Report. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2011/eur/186342.htm. (return to text)

34 U.S. Department of State. July 31, 2012. “Africa Overview.” 2011 Report on Terrorism. http://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2011/195541.htm. (return to text)

35 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Oman.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/nea/192901.htm. (return to text)

36 Decree 92 (Decree on Religious Practice) was promulgated by the Laotian prime minister in 2002 and established the rules for religious practice in the country. See U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Laos.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eap/192639.htm. (return to text)

37 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Morocco.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192899. (return to text)

38 Resolution 16/18 on “Combating Intolerance, Negative Stereotyping and Stigmatization of, and Discrimination, Incitement to Violence and Violence Against, Persons Based on Religion or Belief” effectively tabled a previous U.N. Human Rights Council resolution, supported by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), to penalize the “defamation of religion.” Some critics had equated the earlier resolution with a global anti-blasphemy law. Resolution 16/18 also has received mixed reviews. Some have alleged that it could result in wider limits on free speech. See, for instance, Esman, Abigail R. Dec. 30, 2011. “Could You Be A Criminal? US Supports UN Anti-Free Speech Measure.” Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/abigailesman/2011/12/30/could-you-be-a-criminal-us-supports-un-anti-free-speech-measure/. Others have welcomed the new resolution. See, for example, United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. March 24, 2011. “USCIRF Welcomes Move Away from ‘Defamation of Religions’ Concept.” http://www.uscirf.gov/news-room/press-releases/3570. (return to text)

39 For more information on this event, see U.S. Department of State. March 19, 2012. “The Report of the United States on the First Meeting of Experts to Promote Implementation of United Nations Human Rights Council Resolution 16/18.” http://www.humanrights.gov/2012/04/19/1618-report/. (return to text)

40 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Kuwait.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/nea/192893.htm. (return to text)

41 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Greece.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192815.htm. (return to text)

42 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Denmark.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192803.htm. (return to text)

43 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Kosovo.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?dlid=192825. (return to text)

44 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “India.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/sca/192923.htm. (return to text)

45 U.S. Department of State. July 30, 2012. “Lithuania.” 2011 Report on International Religious Freedom. http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/2011/eur/192831.htm. (return to text)

46 For more information, see World Watch Monitor. Aug. 30, 2011. “Turkey Overturns Historic Religious Property Seizures.” http://www.worldwatchmonitor.org/2011/08-August/article_116880.html/ . (return to text)