Little is known about the religious makeup of the state prison population. Government agencies routinely report on the gender, racial and ethnic composition of inmates in state and federal prisons (see Appendix C) but not on their religious affiliation. One of the central goals of the Pew Forum survey is to offer a glimpse into the religious lives of prisoners through the observations of prison chaplains. The chaplains’ views inevitably are colored by their own attitudes and experiences, so their assessments should be viewed as impressions rather than as facts. Still, their responses to the survey provide some sense of the environment in which they work and of the changes they see occurring.

The chaplains’ estimates of the religious affiliation of inmates are, at best, a very rough indicator. But the estimates suggest that most inmates in state prisons are Christians, albeit with substantial numbers of Muslims, followers of pagan or earth-based religions, practitioners of Native American spirituality and inmates not affiliated with a religion.

About three-quarters of chaplains say that attempts by inmates to proselytize or convert fellow inmates are “very” or “somewhat” common (73%), and a similar portion (77%) say that either “a lot” or “some” religious conversion takes place behind bars. Fewer chaplains say that expressions of extreme religious views are common in state prison; less than half of the chaplains surveyed (41%) say that religious extremism is very or somewhat common in the prison where they work.

When asked to explain in their own words the kinds of extreme religious views they encounter, the chaplains frequently cite two themes: “racial supremacy disguised as religious views” (in the words of one chaplain) and religious exclusivity or intolerance toward other faiths.

A Window into Inmate Religious Preference

The Pew Forum survey asked chaplains whether or not the prisons where they work keep track of inmates’ religious affiliations. An overwhelming majority of chaplains (84%) report that formal tracking systems exist at their facilities. (Such data, however, are not generally publicly available.)

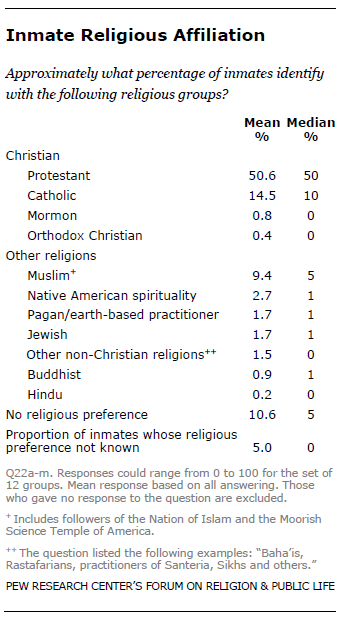

The Pew Forum survey also asked each chaplain to estimate the approximate percentage of inmates in the prison(s) where he or she works that identify with each of 12 religious groups. Of course, some chaplains may have quite a bit of knowledge and others rather little knowledge about the religious preferences of inmates. And, even if chaplains had perfect information about the relative distribution of religious groups among inmates, these findings are not weighted in proportion to the size of each prison’s population and thus cannot provide an accurate estimate of religious affiliation among the U.S. prison population. Nonetheless, these findings offer an impressionistic picture of the religious context in which chaplains work.

The findings suggest that the majority of inmates encountered by most chaplains are Christians. On average, the chaplains surveyed say that Christian groups make up about two-thirds of the inmate population, with Protestants, on average, estimated to comprise 51% of the inmate population, Catholics 15% and other Christian groups less than 2%. The median estimate by the chaplains of the portion of Protestants is 50%, meaning that half of the chaplains estimate that Protestants comprise more than 50% of the inmate population where they work, and half of the chaplains estimate the figure to be below that. There is a wide range of estimates for most of the 12 religious groups, including Protestants and Catholics.

Compared with Christians, other religious groups are seen by the chaplains as considerably smaller in size. Altogether, non-Christian religious groups are seen as comprising about 18% of the state prison population. On average, the chaplains surveyed say that Muslims make up about 9% of the inmate population in the prisons where they work, with half of the chaplains saying that Muslims comprise 5% or less of the population and half saying Muslim inmates make up more than 5% of the inmate population. Other non-Christian groups are perceived as considerably smaller in size (0 to 1% for about half of the chaplains responding).

Further, according to the chaplains surveyed, inmates with no religious preference appear to be a small minority. On average, chaplains say that about 11% of the inmate population is atheist, agnostic or has no particular religious affiliation. The median estimate of inmates with no religious preference is 5%.

By comparison, in the U.S. public as a whole, half (50%) of adults identify as Protestants and about a quarter (23%) are Catholics. About one-in-five adults (19%) are religiously unaffiliated (describing their religion as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular”). Smaller numbers describe themselves as Mormon (2%), Jewish (2%), Muslim (1%), Orthodox (1%) or another faith (3%).18

In a separate survey question, chaplains estimated the percentage of Protestant inmates who consider themselves born-again or evangelical Christians. On average, the chaplains surveyed say that about 50% of Protestant inmates are evangelicals. But their estimates run the gamut, with some chaplains estimating that evangelical Protestants comprise a minority of Protestant inmates and others estimating that a majority of Protestant inmates consider themselves to be born-again or evangelical Christians.

Religious Switching and Proselytizing

How much religious conversion takes place in state prisons? About three-quarters (76%) of the chaplains surveyed say that the prisons where they work maintain formal systems for tracking religious switching among inmates. About three-quarters of chaplains also say that conversion or proselytizing attempts among inmates are either very common (31%) or somewhat common (43%) while about a quarter say such attempts are not too common (22%) or not at all common (4%).

How successful are these attempts? About three-quarters of the chaplains surveyed estimate that religious switching occurs some (51%) or a lot (26%). Fewer say that either not much switching (20%) or none at all (2%) occurs in the prisons where they work.

Chaplains working in maximum security facilities (31%) are more likely than those in medium (25%) or minimum (18%) security facilities to say that “a lot” of switching occurs.

The Pew Forum survey also asked chaplains to estimate whether the ranks of 12 religious groups are swelling, shrinking or stable in the prison population. Among chaplains who report that religious switching occurs in the prison where they work, Muslims and Protestants were the groups most likely to be seen as growing in followers. About half of chaplains answering these questions (51%) report that Muslims are growing in number due to switching; 47% say the same about Protestants in the facilities where they work.

A sizable minority of the chaplains say that followers of pagan or earth-based religions are growing (34%) as are those practicing Native American spirituality (24%) and Judaism (19%).

For nine of the 12 religious groups considered, a solid majority of chaplains answering the question report that the size of each religious group is stable.

For some religious groups, the chaplains answering are more likely to say the group’s followers are shrinking than growing in size due to switching. For example, a fifth (20%) of chaplains answering say Catholics are shrinking in number, while 14% say the ranks of Catholics behind bars are growing. Similarly, 17% of chaplains answering say the number of inmates with no religious preference is shrinking, and 12% say the ranks of the unaffiliated are growing.

In response to open-ended questions on the survey, several chaplains mentioned that inmates may switch to particular religious groups solely to obtain certain privileges or benefits, such as kosher food. Some “inmates adopt Judaism because of the food benefits,” one chaplain wrote. Commenting on religious switching in general, another chaplain said: “You cannot draw any valid conclusions regarding religion in prisons by examining religion changes of offenders. These decisions are primarily privilege based and not religiously based in my experience.”

Other chaplains indicated that they see both half-hearted switching and sincere conversions. “Inmates often return to faith of childhood upbringing,” one chaplain noted, adding: “Some ‘try on’ various faiths. Only a small percentage of inmates seem to take it seriously and stick with it….”

Requests for Accommodation

The Pew Forum survey asked chaplains to estimate how often each of five kinds of requests for religious accommodation are approved or denied. The questions also allowed chaplains to indicate whether or not each kind of request has occurred in the prisons where they work.

Among those answering, an overwhelming majority (82%) say prisons usually approve inmates’ requests for religious books. Seven–in-ten (71%) chaplains answering say requests for visits by religious leaders are usually approved. About half say requests for a special religious diet (53%) and requests for permission to have religious items or clothing (51%) are usually approved.

However, only about three-in-ten (28%) chaplains answering say that requests for special accommodations related to hair or grooming are usually approved. More than a third (36%) say such requests are usually denied.

Some chaplains expressed frustration at the volume of requests for religious accommodation, including requests they view as “using religion to play the system,” in the words of one chaplain.

“Too much of my time is spent on accommodating those ‘using’ religion to get additional privileges, such as better food, religious items, additional packages, gangs trying to meet as religious groups, etc.,” another chaplain wrote in response to an open-ended question on the survey. “I do little ministry but facilitate perpetual changing of religious declarations for the next ‘food’ event or whatever gives the inmate the best gang option or ability to gain personal items,” yet another wrote.

Religious Extremism in the Prisons

The survey asked a number of questions about how often chaplains encounter “extreme religious views” within the prison population. About four-in-ten chaplains say that groups expressing extreme religious views are very common (12%) or somewhat common (29%); a majority says such views are not too common (42%) or not at all common (16%) in the prisons where they work.

Perceptions of the prevalence of extreme religious views tend to vary with the security level of the facility where the chaplains work.

Chaplains in maximum or medium security facilities are more likely than those in minimum security facilities to say that religious extremism is very or somewhat common. About four-in-ten chaplains in maximum security (44%) and medium security prisons (42%) say religious extremism is very or somewhat common, compared with 32% of chaplains who work in minimum security facilities.

These findings are, of course, colored by the perceptual lens of the chaplains responding. For example, assessments of the prevalence of religious extremism among inmates tend to vary with the religious affiliation and race of the chaplains surveyed. Protestant chaplains are more likely than those of the Catholic or Muslim faith to say that religious extremism in the prisons is either very or somewhat common. This tendency is a bit stronger among white evangelical chaplains than it is among white mainline Protestants.

Analysis of these differences is constrained by the modest number of chaplains from some of these faith traditions who are in the survey. For example, 98 respondents are Catholic, and only 53 are Muslim. However, those who are Muslim appear less likely than other chaplains to perceive a lot of religious extremism among inmates. Just 23% of the Muslim chaplains say religious extremism is either very common or somewhat common in the prisons where they work, while 43% of Protestant chaplains take that view. Catholic chaplains fall in between, with 32% saying religious extremism is very or somewhat common in the facilities where they work.

The survey also asked chaplains to estimate how often extreme views occur among inmates in each of 12 religious groups. Respondents were able to indicate if no inmates belonged to a particular group.

Of the chaplains expressing an opinion on these questions, a majority say it is very common (22%) or somewhat common (36%) for Muslim inmates to express extreme views. This includes inmates who belong to such groups as the Nation of Islam and the Moorish Science Temple of America, which traditional Muslims may view as unorthodox or heretical. (See Glossary.)

A sizable minority (39%) of chaplains also say religious extremism is very or somewhat common among inmates who practice pagan and earth-based religions (such as Asatru, Odinism and Wicca). Roughly one-fifth to one-quarter of chaplains with an opinion say religious extremism is very or somewhat common among Protestant inmates (24%), inmates who follow other non-Christian religions, such as Rastafarians and practitioners of Santeria and Voodoo (21%), and those practicing Native American spirituality (19%). (See Glossary.)

Interestingly, perceptions of religious extremism vary strongly with the security level of the chaplains’ facility for only one of the 12 religious groups – Muslims. Chaplains in maximum security facilities are more likely than those in either medium- or minimum-security facilities to say that extremism among Muslim inmates is very or somewhat common. Perceptions of the prevalence of religious extremism among inmates from other faith groups is not related, or only modestly related, to the facility security level.

The relative rankings of the top two inmate groups most associated with extremism are the same for chaplains working in each security level. Regardless of security level, the chaplains answering are most likely to say that extremism is very or somewhat common among Muslim inmates, followed by adherents of pagan or earth-based religions.

To better understand what is meant by religious extremism, the survey also asked chaplains to explain in their own words the kinds of extreme religious views that they encounter in state prisons. Overall, 62% of chaplains provided some response. Not surprisingly, those who say that encountering extreme religious views among inmates is very or somewhat common were more likely to respond to the question (82% answering) than were those who say that such views are not too or not at all common (47% answering).

Chaplains offered a wide range of comments to this open-ended question. Their responses were categorized according to the ideas or themes they suggested and, separately, according to the specific religious groups they named as espousing extreme views. Many chaplains mentioned multiple ideas or religious groups.

Among the chaplains responding, two themes are common. A net of 41% of those responding mention racial intolerance or prejudice against specific social groups. This figure includes references to views of black or white racial superiority and racial supremacy (36%) as well as hostility toward gays and lesbians, negative views of women (particularly in religious leadership roles) and intolerance toward sex offenders or other inmates based on the nature of their criminal offense. “Racially based beliefs are held by Odinist/Wotanist inmates and members of the Nation of Islam,” one chaplain noted. Another cited “demands that some inmates cannot be a part of the religious group because of sexual identity and/or sexual crimes.”

A nearly equal percentage (40%) of those responding mention religious intolerance. This figure includes references to views of exclusivity of faith and “religious bigotry” (32%) as well as references to those seeing only the King James Bible as authentic, espousing “militant” faiths, or attempting to intimidate or coerce others into belief.

A little more than a quarter (28%) of the chaplains responding cite specific requests for food, clothing or rituals in their descriptions of extremism. And some (22%) describe religious extremism in other ways, such as prisoners using religious groups as a cover for non-religious activities, espousing views that promote violence or rape, and creating new religions. (Note that percentages do not add to 100% because multiple responses were allowed.)

A wide range of groups are mentioned in connection with extreme religious views. Among chaplains responding, the most commonly mentioned group is Muslims (54%, including 21% who specifically cite the Nation of Islam). In addition, 34% mention Christians, including 7% who specifically cite evangelical or fundamentalist Protestants, 6% who mention Hebrew Israelites and 4% who cite followers of the so-called Christian Identity movement.19 Many chaplains also refer to other religions (net of 43%) in connection with religious extremism, including pagan or earth-based religions (16%) and Satanism or devil worship (12%).

To better understand what chaplains have in mind, the Pew Forum looked at the subset of respondents who cited the two most commonly mentioned religious groups (Muslims and Christians) in addition to some kind of thematic explanation of extremism. Among chaplains who mention Muslims and also provide some kind of thematic explanation (83 chaplains or 18% of those responding), about half (51%) mentioned Muslims in connection with the idea of racial and social group intolerance and about four-in-ten (41%) mentioned Muslims in connection with the idea of religious exclusivity. As an example of extremism, one chaplain cited “racism from the [I]slamic groups,” while another listed “Muslims who think their view of Islam is the only way.”

Among chaplains who mentioned Christians and also provided some kind of thematic explanation of extremism (52 chaplains or 12% of those responding), about two-thirds (67%) mentioned Christians in connection with the idea of religious exclusivity while 37% mentioned Christians in connection with the idea of racial and social group intolerance. One chaplain commented, for example, that “… some fundamentalist Christian organizations have found it difficult to respect the religious boundaries of others.” “On my unit there is a struggle between the Arminians (conditional salvation) and Calvinist (once saved always saved),” another noted. “We have had issues with white supremacy groups trying to start ‘Christian Identity’ services that [are] hate filled…,” a third chaplain wrote. These are just a few of such responses.

Thus, both kinds of extremism (racial intolerance and religious exclusivity) are perceived to exist among Muslim and Christian inmates, but religious exclusivity appears to be more strongly associated with Christian inmates, while racial and social group intolerance appears to be more strongly associated with Muslim inmates.

Does religious extremism threaten the safety and security of the prison environment? About three-quarters (76%) of chaplains say that religious extremism poses a security threat either “not too often” or “rarely or almost never.” About a quarter (23%) of chaplains say extremism “almost always” or “sometimes” poses a threat to security.

Those working in maximum security facilities are more likely than those working in other kinds of facilities to say that religious extremism poses a threat to security at least sometimes. About three-in-ten (29%) chaplains from maximum security facilities say that extremism is almost always or sometimes a threat to prison security; this compares with about a fifth of chaplains in medium security (19%) or minimum security facilities (18%) who say the same. However, upwards of seven-in-ten chaplains from any of these facility types say that religious extremism rarely, almost never, or “not too often” poses a threat to facility security.

What kinds of measures have state prisons taken to reduce the possibility of security threats stemming from religious extremism? The survey asked about four kinds of possible measures. A sizable minority of chaplains say the prisons where they work have consulted with experts in dealing with religious groups in which extremism is suspected (45%) or have provided additional supervision for religious gatherings (44%). In addition, about a third of chaplains say the prisons where they work have limited the number of gatherings held by religious groups (35%) or isolated particular inmates (33%) to address religious extremism.

Footnotes:

18 Figures for the general public in the U.S. are based on aggregated surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press between January and December 2011. (return to text)

19 As previously noted, Hebrew Israelites are categorized in this report as a Christian group because they historically come out of Christian denominations, but members of the group may view themselves as Jews and some chaplains may consider them to be Jews as well. (return to text)

Photo Credit: © Illustration Works/Corbis