A new comprehensive survey by the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life examines Mormons’ beliefs and practices, political ideology, and attitudes toward their faith, family life, the media and society. In a conference call with journalists, the Forum’s staff discussed the findings of Mormons in America: Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society. The survey was conducted between Oct. 25 and Nov. 16, 2011, among a national sample of 1,019 respondents who currently describe their religion as “Mormon.” It is the first nationally representative survey of Mormons ever undertaken by a non-LDS research organization.

Speakers:

Greg Smith, Senior Researcher, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

David Campbell, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Notre Dame

Matthew Bowman, Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion, Hampden-Sydney College

Moderator:

Luis Lugo, Director, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

Navigate This Transcript:

Not in the Mainstream But Gaining Acceptance

High Level of Religious Commitment

Ideologically Conservative and Republican

Moderate Views Toward Immigration

Younger Mormons More Politically Conservative

A Community Within the American Community

Missionary Experience Affecting Attitudes

Parallels With the Muslim Experience

The “Cult” Word

OPERATOR: Hello and thank you for joining us today for the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion and Public Life’s Q&A session on the findings from a new survey, Mormons in America: Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society.

Luis Lugo, director of the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, will moderate the discussion, and Greg Smith, the Pew Forum’s senior researcher and lead author of this survey, will present the findings. They are joined by two members of the survey’s advisory board — David Campbell, associate professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, and Matt Bowman, visiting assistant professor of religion at Hampden-Sydney College. We will go to the question and answer portion after brief remarks from our speakers.

Please note this call is being recorded and I’ll be standing by should you need any assistance. It is now my pleasure to turn the conference over to Mr. Luis Lugo. Please go ahead, sir.

LUIS LUGO, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: Thank you. Good morning to all of you, and thank you for joining us today to discuss the findings of our national survey of Mormons. As far as we know, this is the first survey of its kind ever published by a non-LDS research organization. I’m Luis Lugo, as was mentioned; I’m the director of the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. As many of you know, we are a project of the Pew Research Center, which is a nonpartisan organization that does not take positions on issues or policy debates.

The idea for this survey came about this past summer when some articles in prominent media outlets declared that the U.S. was experiencing a “Mormon moment.” Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman had made clear their presidential aspirations. Mormon author, Stephenie Meyer, was in the spotlight for her bestselling “Twilight” vampire novels. And the hit musical “The Book of Mormon” was playing on Broadway.

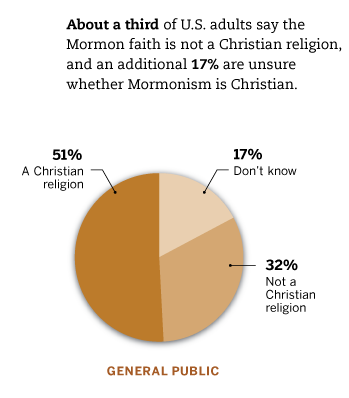

A Newsweek article stated that despite the sudden proliferation of Mormons in the mainstream, Mormonism itself wasn’t gaining any mainstream acceptance. Indeed, in a survey we conducted this past November, half of Americans told us that they know very little or nothing about Mormonism. And as you folks well know, we’re not a country of particularly tough graders. The same survey found that one-third of U.S. adults say the Mormon faith is not a Christian religion, and another fifth or so say that they are unsure whether Mormonism is Christian. In an open-ended question, we asked what one word best describes the Mormon religion. The most commonly offered response: cult.

So we know something about what the general public knows and thinks about Mormons, but what do Mormons themselves think about their place in American life? With the rising prominence of members of the LDS Church in politics, popular culture and the media, do Mormons feel more secure and accepted in American society? And what exactly are their religious beliefs and practices? This new survey seeks to answer these questions and more.

Please note that in this survey we’ve defined Mormons in the same way that we define other religious groups in all our surveys, that is, through self-identification. So this survey covers people who currently describe themselves religiously as Mormon. This means that people who might think of themselves, say, as ethnic Mormons but not Mormons in a religious sense may not necessarily be captured in this survey.

While this survey comes in the midst of an election campaign, it is not primarily about politics. Rather, we hope that it will contribute to a broader public understanding of Mormons and Mormonism in American society. We see this quite simply as part of the Pew Forum’s continuing efforts to generate and widely disseminate information about important issues at the intersection of religion and public life in the U.S. and around the world.

As was mentioned, we’re pleased to have on the conference call with us two outside experts who served on our advisory board for this survey, Matt Bowman of Hampden-Sydney College and David Campbell of the University of Notre Dame. Matt and Dave will share what they find most interesting about the survey and also will be available to answer your questions. Please note, though, these folks do not speak for the Pew Forum, so we’d ask that you identify them in terms of their academic affiliation. I’m sure their institutions’ communications departments would appreciate that as well.

Now I’d like to turn things over to Pew Forum senior researcher Greg Smith, who is the lead author of this report and who will briefly discuss the findings. Thanks again to everyone for joining us. Greg, over to you.

GREG SMITH, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: Thank you, Luis. As Luis mentioned, one of the key questions we aimed to explore with this survey was: How are Mormons in the U.S. experiencing and responding to this “Mormon moment” that we seem to be in? What the survey finds is a mixed picture. On the one hand, many Mormons tell us that they feel misunderstood, discriminated against and like they’re not accepted by other Americans as part of mainstream society. You can see this in responses to a number of the survey’s questions.

For example, when asked how much the American people as a whole know about the Mormon religion and its practices, six-in-ten Mormons say that the American public knows little or nothing about Mormonism. When asked to describe in their own words the most important problems facing Mormons living in the United States today, a majority mentioned things like misconceptions about Mormonism, that Mormons are not seen as Christian, or that Mormonism is still associated with polygamy or seen as a cult. And fully two-thirds of Mormons tell us they think that the American people as a whole do not think of Mormonism as part of mainstream American society. Clearly then, this is a population that in many ways still sees itself as being on the periphery of American society and looking in.

On the other hand, however, the survey also shows that in many ways Mormons are happy with their own lives and see acceptance of Mormonism as on the increase. There are indications that they view themselves as a group that’s on the way up, you might say. For example, even though most Mormons don’t think Mormonism is currently seen as mainstream by the American people, most Mormons do think that the public is becoming more likely to see Mormonism as mainstream. The survey also shows that nearly nine-in-ten Mormons say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their own lives, and a similar number rate their communities as excellent or good places to live. These numbers exceed what we see among the public as a whole.

And in response to what I personally think is one of the most interesting questions in the study, the majority of Mormons we spoke with say they think that the American people as a whole are ready to elect a Mormon as president. Now, I should point out that while it’s impossible to know for sure precisely what mix of considerations might underlay the findings on this question, we tend to think of it more as an indicator of Mormons’ attitudes about their acceptance and incorporation into American society, rather than as a concrete political prediction. The question came right after those I mentioned previously about acceptance of Mormonism, and it was separated from more explicitly political questions, like views of the presidential candidates, political partisanship and the like.

So when it comes to their views of their place in American society, we see a mixed picture. This is certainly a population that is acutely aware of the reservations that many Americans have about Mormonism. But it’s also one that’s comprised of people that are largely satisfied with their own lives and that perceives itself as increasingly seen as part of the mainstream.

Another area that the survey explores in some depth is religious beliefs and practices. In what ways do Mormons resemble the broader public, religiously speaking, and in what ways are they distinctive? The survey finds areas of commonality between Mormons and traditional Christianity. Nearly all Mormons, for instance, say they believe in the Resurrection, that Jesus rose from the dead. And nearly all Mormons assert that the Mormon religion is, in fact, a Christian religion.

Another finding that leaps out of these data is that Mormons have very high levels of religious commitment. Three-quarters tell us that they attend religious services on a weekly basis. And upwards of eight-in-ten tell us that they pray every day and that religion is very important to them in their own lives.

Combining these questions, we find that roughly seven-in-ten Mormons exhibit high levels of religious commitment in that they possess all three attributes: they say they attend church at least once a week, and they say they pray every day, and they say religion is very important in their lives. By comparison, among the public as a whole, less than half as many display high levels of religious commitment.

I should take this opportunity, while discussing their uniquely high level of religious commitment, to reiterate what Luis mentioned and provide a reminder about just who is in our current sample and who is not. Our survey covers people who currently describe their religious identity as Mormonism. It does not cover former Mormons. It does not cover people who might think of themselves as Mormons but solely in ethnic terms or because of their family background.

We would expect that an alternative survey with a sampling frame drawn, say, from church membership lists, which might include both active and inactive members, might well generate different results than the current approach. I say this, again, just to reiterate that it’s important to keep in mind just who we’ve surveyed here, which are people who currently think of themselves, religiously speaking, as Mormons. In any event, the approach we’ve adopted here is just the same one that we used to define other religious groups in our surveys, which is to say through self-identification. And the high degree of religious commitment displayed by this community is striking.

Getting back to the topic at hand, the survey confirms that Mormons are a highly religiously committed group with important commonalities with traditional Christianity. But it also shows that Mormons are united in affirming a number of tenets that are central to the teachings of the LDS Church and that are distinct from traditional Christianity. For example, nine-in-ten Mormons say they believe that the president of the LDS Church is a prophet of God. Nearly all believe that families can be bound together eternally in temple ceremonies. And nearly all believe that God the Father and Jesus Christ are separate, physical beings.

Turning from religion to politics, the survey confirms that Mormons are a highly conservative and Republican constituency. Two-thirds of Mormons describe their political ideology as conservative, which is far higher than the number saying the same among the general public. And nearly three-quarters of Mormon registered voters describe themselves as Republicans or say they lean toward the Republican Party, again a rate of affinity for the GOP far exceeding that seen among the public as a whole.

The survey also shows that Mormons have a highly positive view of Mitt Romney. Even Mormon Democrats view Romney in a positive light. In fact, his favorability rating is as high among Mormon Democrats as it is among Republicans in the general public. By comparison with Romney, Jon Huntsman is viewed somewhat less favorably by Mormons, with one-quarter of Mormon voters unable to rate Huntsman at all. Huntsman does, however, have a strong 70 percent favorability rating in Utah, where he used to be the governor and where he is much better known than he is nationally.

Finally, to conclude these remarks, I’d like to say just a word or two about what the survey says about the relationship between Mormons and evangelicals in the United States — two groups whose relationship with one another has increasingly come under the microscope. The survey confirms that these are two groups that have a fair amount in common with each other politically speaking, in that large numbers in both groups are ideologically conservative and Republican in their partisan leanings. In some ways, Mormons and evangelicals also resemble each other and stand out from the broader public in their religious characteristics, in that majorities in both groups exhibit high levels of religious commitment.

Yet Mormons perceive that there’s a significant degree of hostility directed toward them from evangelical Christians. Fully half of those surveyed say that evangelical Christians are generally unfriendly toward Mormons. And this perceived hostility we think reflects findings from other Pew polls that show that evangelicals express reservations about Mormonism. Roughly half of white evangelical Protestants say that Mormonism is not a Christian religion. And two-thirds say that Mormonism and their own religion are really pretty different from one another. So the tension between these groups is significant, it’s real, and it’s certainly firmly on the radar screen of the Mormons that we spoke with in doing this survey.

I hope these remarks provide a basic sense of some of the highlights and the main themes that emerge from the survey. I’ll now turn the floor back over to Luis, and I look forward to responding to your questions.

LUGO: Thank you, Greg. David Campbell from the University of Notre Dame, if I could ask you for your comments next, please.

DAVID CAMPBELL, UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME: Sure. What I thought I would do is highlight a few things that I think are notable from the study, and I’d like to begin with a political question. Greg, I think, accurately characterized the Mormon population as being highly conservative, strongly Republican, and that will not come as a surprise to anyone. But what might be a little surprising is the fact that on at least one issue Mormons actually would not be ranked among the most conservative in the country, and that is immigration.

Mormons are actually far more positive toward immigrants than are evangelicals, another highly conservative group. And they’re quite a bit more positive toward immigrants than are mainline Protestants, white Catholics and black Protestants. So, in other words, on one of the most hot-button issues in politics today, especially among conservatives, Mormons are actually quite moderate, I would say. The average Mormon opinion of immigrants looks just like the rest of the general public, which, again, is remarkable given the general political conservatism that we find within Mormonism.

There are undoubtedly a variety of reasons for that. The LDS Church itself is actually quite moderate — you might even say, a voice of compassion — on the question of immigration. And of course, many Mormons serve as missionaries abroad, where they learn a foreign language and they spend up to two years with people of another culture, and that undoubtedly leads to a greater appreciation for immigrants here in the United States. So that’s one thing that I thought was remarkable.

Another, also sticking with politics, is that if you look at the age breakdown of Mormons and who describe themselves as political conservatives, we find among Mormons a trend that is exactly the opposite of what you find in the general population. In general, younger people are more likely to refer to themselves as liberal or less likely to call themselves conservative than are older people, and that shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone.

But among Mormons, it’s exactly the opposite, actually. It’s the younger Mormons who are more likely to describe themselves as conservative than are older Mormons, and that’s likely because these older Mormons came of age, at least politically, in an era when there was greater political diversity among Mormons. The almost monolithic Republicanism among Mormons is a relatively recent innovation over roughly the last generation or so, so say 25 or 30 years. But prior to that, you found much more partisan diversity among Mormons, and that’s reflected in the survey.

Let me just comment on a few other things that I thought were interesting. Another contrast between Mormons and what you find in the general population — among Mormons, you find that greater education, and that is, a greater level of education, corresponds to greater — maybe orthodoxy is the way to describe it — greater adherence to the beliefs of Mormonism. Now in other religious groups, more education correlates with more religious attendance and religious behavior. So it’s a misnomer that in America religion is only for the working class or for the poor. That’s actually not true. In general, churchgoing is a very middle-class activity in the United States.

But among other religious groups, highly educated people, while they might be participatory in their religion, don’t necessarily hold to orthodox beliefs within their faith. That’s not the case with Mormons. The more education Mormons have, the more likely they are to say that they believe wholeheartedly in everything within Mormonism, and then the more likely they are to subscribe to the particular tenets of the faith.

Let me close my remarks with just one further observation that I thought was interesting and that relates to something I mentioned earlier, the missionary service that so many Mormons engage in. We find in the survey that missionary service, that is, people who have served as full-time missionaries for the LDS Church, actually correlates with thinking that other religions are similar to Mormonism. So it seems as though serving as a missionary for the church, where your objective is to convert others to Mormonism, appears to foster a greater appreciation for other religions or, at the very least, fosters an appreciation for what Mormonism has in common with other religions, which is interesting because you might have thought it would actually go the other way, that serving as a missionary would only serve to accentuate the differences between Mormonism and other religions. But it doesn’t seem to pan out that way.

I’ll conclude my thoughts there, but I’m happy to answer other questions as the conversation proceeds.

LUGO: Terrific. Very interesting, David. Thank you so much. Now, from Virginia’s beautiful Southside District, Matt Bowman from Hampden-Sydney College.

MATTHEW BOWMAN, HAMPDEN-SYDNEY COLLEGE: Hi there. Thank you. I would like to build off something that Dave just said, particularly with reference to immigration. He mentioned that it’s quite possible that Mormons are moderate on immigration because this is their church’s position, and because the church itself is transnational in a lot of ways, and because many Mormons interact with immigrants as well. I think this points to something that I think the survey illustrates quite well, which is many Mormons’ ambivalence towards their position in American society. On one hand, they feel a strong desire to participate in American society; on one hand, they are satisfied with their lives in America — 56 percent think that America is ready for a Mormon president.

But at the same time, there’s also a powerful sense that the Mormons are what the former president of the church, Gordon B. Hinckley, used to call “a peculiar people,” quoting the Bible. That is, 68 percent of Mormons believe Americans don’t think that Mormons are part of mainstream culture. Nearly half feel that they suffer discrimination in American society, and nearly six-in-ten say that most or all of their close friends are Mormon. So there is then this strong sense of themselves as a community, as a people who are different from the society around them, while at the same time wanting to participate in that society.

I’d also like to point to one other factor that I think illustrates this in an interesting way. One of the survey questions asked Mormons to comment on what they thought was essential to being a good Mormon. Many of the factors here were traditional boundary markers of behavior, things like the Word of Wisdom, which prohibits Mormons from consuming alcohol, tea, coffee or tobacco, or not watching R-rated movies. Many Mormons did affirm those. But 73 percent of Mormons said that feeding the poor, that helping the poor, was essential to being a good Mormon.

At the same time, however, 75 percent believe that America needs a smaller government with fewer social services. Now this would seem to be initially in disjunction, one with another. But I think it points actually to the church’s powerful, powerful sense of itself as a community. There is a very strong welfare system active in the church. Many Mormons participate in this welfare system to take care of their own, to take care of other people in their communities.

I think, then, that this illustrates one way in which Mormons are kind of a community within the broader American community. They have both of these identities — their identity as a Mormon, as a member of their church, but also in American culture more broadly. I think this survey does a great deal to illustrate this tension between the two. I will be happy to take questions on that as well.

LUGO: Thank you so much. Again, as a reminder, please identify both David and Matt with their respective institutions rather than the Pew Forum — unless, of course, the reference is to them having served as advisers on this survey, and then we’re happy to own them. I should mention that we also have with us — though struggling with a bad cold — Alan Cooperman, the Pew Forum’s associate director for research, who worked closely with Greg on this report and who will also participate in the Q&A.

Again, if you want to direct your questions specifically to either Matt or David, please indicate that so that we can direct those to them. But I’m sure we’ll get them into the discussion in any case because I have some questions for them, particularly on candidate Romney and immigration questions and so forth. But there is a lot of good stuff there to chew on.

But you’ve been very patient. There are a lot of you on this conference call, which we appreciate — our friends from the media — so let’s get directly to your questions.

MITCHELL LANSBERG, LOS ANGELES TIMES: Yes, hi. This is a question for David. You talked about the support for immigration, and you speculated that the missionary experience might have something to do with that. Did the survey actually indicate that Mormons who had been missionaries were more likely to support immigrants?

CAMPBELL: I’m just actually looking at the report —

LUGO: David, we have our team here too of numbers-crunchers, so we’ll — I’m not sure that particular point was made in the report, but we certainly have that data and we’ll —

SMITH: I’m just looking at it now. The question we asked about immigration is this: Which statement comes closer to your own views, even if neither is exactly right? Would you say immigrants mostly strengthen our country because of their hard work and talent, or would you say that immigrants are a burden on the country because they take American jobs, housing and health care?

What we find is that there is a significant link there between having served a mission and views on this question. Among Mormons who had served a mission, 56 percent say that immigrants strengthen our country. That is significantly higher than what we see among those who have not served a mission, among whom 41 percent say that immigrants strengthen our country. So there does appear to be a significant link between missionary experience and attitudes toward immigration.

LUGO: David, please add to that.

CAMPBELL: The addition I would make is that you see in the data that having served as a missionary does seem to have a relationship to the way you perceive immigrants. But I would suggest that the pervasiveness of missionary service within the LDS Church and within the Mormon culture is such that you probably don’t even have to have served a mission yourself to have this appreciation.

It’s very common in Mormon congregations if a missionary has served abroad, particularly in a more exotic place, to come back and speak about it, show slides and pictures, and give presentations to youth groups. Many Mormon families speak at great length about family members of theirs who have served for two years in Portugal or in Japan or in Mexico or wherever else. It’s a community that I think is very cosmopolitan, or at least aware of international culture, because of this high level of missionary service. So it’s not just that individuals themselves have served, but also that you’re sort of in this culture where the service is quite common and commonly referred to.

SMITH: Just to add to that and reiterate, the data are certainly consistent with that. We see that there is a link, for example, between level of religious commitment and attitudes toward immigration, with people who have the highest levels of commitment also the most favorably disposed toward immigrants. So that would certainly be consistent with David’s comments, given that it’s the most highly religiously committed people who are probably most likely to be surrounded by and in conversation with people with missionary experience, regardless of whether or not they themselves have served.

LUGO: But to add just a little bit on that, isn’t it also the case, though, Greg, just to look at this from another dimension, that those Mormons who had served a mission also indicated a higher degree of hostility from evangelicals? Or am I making that up?

SMITH: I think that’s right. Let’s see here; yes, those people who had served a mission are more likely than those who have not to say that evangelicals are mostly unfriendly toward the Mormon religion. And that seems to be specific to attitudes toward evangelicalism because we don’t see the same kind of linkage with respect to missionary status and opinions as to whether or not people who are not religious are friendly toward Mormons. That’s right.

LUGO: And David mentioned generally more openness on the part of those who had served a mission, but there is the evangelical exception here, which I think is also quite interesting and bears repeating.

RICHARD ALLEN GREENE, CNN: I guess my question is primarily for Dave and for Luis. I was struck, reading the report, on the degree to which I think you could substitute the word Muslim for Mormon through a lot of this report in the sense in which you’ve got a small minority community, they don’t feel particularly accepted, but they are still comfortable in the country and they feel they are gaining more acceptance.

And Dave, it put me in mind of “American Grace,” in the sense that this is a particular example of a much broader American experience. You’re not going to get the Muslims, obviously, saying they’re overwhelmingly Republican. But on the broad picture about acceptance and belief and belonging and community, how much is the Mormon experience simply a particular example of the American religious experience?

LUGO: Fascinating question, Richard; thank you. David, why don’t you go first, and then I will ask our folks here to weigh in? We have done two major surveys of Muslims in the U.S., and so there are some interesting comparisons to be made indeed.

CAMPBELL: Well, thank you very much for the reference to “American Grace.” For those who may not know what he’s referring to, that’s a book I published with Bob Putnam of Harvard about a year ago. In that book we asked the question of how America can be religiously devout as a country, religiously diverse and also religiously tolerant. Most Americans are quite comfortable with people of other religions, but there are some exceptions. One is the Muslim community and another is the Mormon community, although they’re not the only two exceptions; there are others. We find that, for example, Buddhists are also not viewed necessarily very positively by the American public.

All three of those groups — and undoubtedly there are others as well — share characteristics, like they’re relatively small, they’re relatively insular, and most importantly, they’re not well-known to other Americans. And so, in the broad contours I would say, yes, there is a parallel between the Mormon experience in America and the Muslim experience and the experience of other small and distinctive religious groups — the Sikhs come to mind, for example.

But I think when you get into the specifics, there are some unique features of Mormonism that undoubtedly frustrate many members of the LDS Church as to why they don’t have greater acceptance. This is, after all, a religion that was born in America; it’s a religion that’s been in the United States for a long time. And numerically, there are a reasonably large number of Mormons — there are about as many Mormons in America as there are Jews, and yet Mormons still feel that they are not fully accepted by the mainstream of America.

I think that that speaks to the distinctiveness of Mormonism. But I wouldn’t want to make too much of the Mormon-Muslim connection, just because, while they, as I said, are consistent in some of the broad contours, there are some unique features of Mormonism that I think are particularly telling. I’ll leave it at that.

SMITH: Just picking up on what David said, I certainly agree that I think that there are some important differences between the Muslim community and the Mormon community. Muslims, we know from our surveys, are primarily an immigrant population; Mormons are not. Muslims are primarily composed of racial and ethnic minorities; Mormons are not. Mormonism has its roots in the United States; Islam does not. So there are these important differences. And, Richard, you mentioned some of the political differences between the two groups, which are also very real and very large.

But what I was struck by sounds like very much what you were struck by, Richard, in the sense that despite these differences, we do see a remarkable degree of similarity in terms of their perceptions of what it’s like to be part of their group in American society. Muslims, very much like Mormons, are under no illusions, in the sense that they recognize that it’s an uphill battle, so to speak, to gain acceptance; that they’re often discriminated against; that they think people largely don’t understand their faith; that their treatment by the media isn’t always fair. We see the same kinds of things among Mormons.

But again, despite this, members of both groups overall express high levels of satisfaction with their lives in the United States and express a high degree of optimism. So I think that there are some important similarities there, despite some very real differences in terms of their characteristics and their history in the United States.

LUGO: Yeah, that’s a very nice way to put it in terms of the challenges, but also the fact that both groups are relentlessly positive about the U.S. and their future in it.

BILL TAMMEUS, THE KANSAS CITY STAR: I have a quick clarifying question and then a real question. It looked to me as though you allowed people who are members of the Community of Christ, which used to be the reorganized Latter-day Saints Church based here in the Kansas City area, to be part of this, but it looks to me as though nobody participated from the Community of Christ. I wonder if you’d clarify that.

And then let me go ahead and ask the question. It’s a question about the bias against Mormons. Were you able, or were Mormons themselves able, to determine whether this stems primarily from ignorance, or is it a case of theological familiarity breeding contempt?

SMITH: To answer the first question, anyone who describes their religion as Mormonism is eligible for this survey. The question that we asked people is: What is your present religion, if any?

TAMMEUS: I’m looking at what was given there, which told me nobody participated.

SMITH: Well, that’s right. We asked: Are you Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, Hindu, atheist, agnostic, something else or nothing in particular? Anybody who answered that question by describing themselves as Mormon was eligible to participate in our survey. Now, subsequent to that question we asked a follow-up, which was: And is that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Community of Christ or some other Mormon church?

In practice, upwards of 99 percent of all of the self-identified Mormons confirmed that they are part of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as opposed to some other church. So on the one hand, yes, the survey was open to Mormons who might not consider themselves part of the LDS, but in practice, hardly any of them actually participated.

With respect to the second question, maybe I’ll say just a couple words and then see if David and Matt have some additional thoughts. It’s an interesting question. I don’t think the data suggests that Mormons think this is contempt bred of familiarity, in the sense that six-in-ten Mormons tell us that they think most people know little or nothing about Mormonism. So I don’t think there’s any evidence there to suggest that Mormons feel like their faith is understood and disliked nonetheless.

With that said, I think you also see in response to other questions that regardless of how much Americans may actually know, factually speaking, about Mormonism, there certainly is the realization on the part of Mormons that many Americans have conceptions, have ideas, about Mormonism that may or may not be accurate and that in many cases are negative. We have lots of Mormons telling us that they feel like most people don’t view them as Christian; that they feel like people view their faith as a cult; that they feel like they’re too often associated with polygamy. So it’s not so much that there’s a feeling that it’s familiarity that’s breeding these things, but maybe there are significant misconceptions that are associated with them.

LUGO: Yeah, that’s helpful. Let me actually ask Matt to jump in here because I’m much taken with the sort of tension between remaining a peculiar people, sort of internally coherent and solidified, versus joining the mainstream. I mean, this question is not unrelated to that. Do you find, Matt, historically, that that’s part of the hesitation on the part of some Mormons in terms of joining the mainstream, that familiarity could breed more contempt towards Mormons?

BOWMAN: Sure and I will address that. But another point I think that’s worth making about the Community of Christ is that the word “Mormon” is a contested term, and many members of the Community of Christ would not use that to describe themselves. So it is possible that that screened out some of them.

As to the theological question, I think there is an extent to which many Mormons would feel that beliefs which seem normal and compatible with being American, like, say, having a prophet or being in a relatively authoritarian church, are things that other Americans find un-American and difficult. We’ve seen a lot of comparison recently between John F. Kennedy and Mitt Romney, and it strikes me that much of the criticism that Mormons feel directed at them today is similar to that which was directed at Catholics 50 years ago. That is, they belong to an authoritarian church; they are not really Christian; their church is ritualistic and strange, not individualistic like American Protestantism is.

But Mormons would not reject those things; Mormons feel that their priesthood hierarchy and all the rest are not incompatible with being a member of American society as well. So there is, on the part of many Mormons, great confusion about why exactly they are distrusted so much.

ALEX ROARTY, NATIONAL JOURNAL: I was just wondering if you guys in the survey had come up with a figure in terms of the evangelical Protestants — I mean, if you asked how many of them would be comfortable with Mitt Romney as president, or whether or not they would vote for a Mormon as president. Did that come up at all?

LUGO: Thank you, Alex. We did, in fact, probe that question, not in this particular survey, which was just of Mormons, but in the survey we did not too long ago. So maybe, Greg, you’d like to address that.

SMITH: Sure. The most recent research we’ve conducted on that question comes from a poll that we conducted in November. And it was really interesting. What we found there is that Romney’s Mormonism may well pose a stumbling block, or may well prove problematic, in the campaign for the Republican nomination. And what we find is that evangelicals are the group among which he faces the biggest uphill battle.

Romney, at that time, was not the favored candidate of evangelical voters in the GOP. And even though most of the people that we spoke with said that Romney’s religion wouldn’t make them any more or less likely to vote for him, the number saying that his religion would make them less likely to vote for him was a little bit higher among evangelicals in the GOP.

So there is this real evidence that Romney’s Mormonism could be a factor in the nomination campaign. However, the same survey also showed that evangelicals, the same people who might be most concerned about Mormonism and about Romney’s religion, are the same people who are most strongly opposed to Barack Obama and most strongly committed and desirous of seeing a new administration come a year from now.

What we see in the survey is that if he secures the nomination, Romney’s advantage among evangelicals over Obama is just as large as it would be for any other Republican candidate. So while it may be a stumbling block in the nomination campaign, it doesn’t look like it would have any impact on his support among core GOP constituencies in a general election.

LUGO: Yeah, and it underscores what you had said previously, Greg, namely, that there are theological differences and those are magnified when the context is a fight within the Republican Party. Once you move it to a larger context, where the fight is between Republicans and Democrats, and Barack Obama more specifically, then the political inclination and the ideology really surface. So any reservations about Mormonism are going to be trumped by their intense dislike of Barack Obama. I think it’s getting a sense of that tension within evangelicals themselves. Within the Republican Party, that’s one thing; once we get to the general election, that’s a whole different ballgame.

NAOMI RILEY, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL: I was wondering if anything in your survey would allow us to make a distinction between personal animosity that individual Mormons are experiencing from the doctrinal suspicion that we’ve been talking about. One thing that leads me to ask that question is you said the majority of Mormons — the vast majority — seemed very happy with their own communities. I don’t know whether they mean by community their own religious community or their own larger community. But if they mean their own larger community, I wonder if on a personal basis, they are not experiencing any kind of individual animosity and it’s really a broader feeling that they’re getting from the country as a whole.

LUGO: That’s a very good question, Naomi. In fact, remember in the Muslim survey we found that a much smaller percentage of Muslims told us they personally had experienced discrimination than those who said that Muslims in general are experiencing discrimination. I think this question is along those lines.

SMITH: I’ll say just a couple words, and then maybe we can see if Dave or Matt have anything to add. It’s an interesting question. We don’t have questions on this survey that ask Mormons whether or not they personally have experienced various types of discrimination. Rather, most of the questions that we have ask them about challenges that Mormons in general may or may not face.

Part of the reason for that is simply space. We were limited for time in the survey. But there’s also another reason, which is to say that unlike Muslims, Mormons tend to be more geographically concentrated. In fact — we can talk more about this; this is probably too inside baseball — that actually made this survey a little bit easier to conduct than, say, the Muslim American survey because it’s more apparent as to where to conduct interviews if you want to find Mormon respondents.

So since they tend to live in areas — which isn’t true of all Mormons — but since there’s a tendency to live in areas with more Mormons, the questions about personal experiences with discrimination seem like they might be a little bit less relevant for that community. However, the data are suggestive in this respect: The question that we asked about satisfaction with your community really was about your geographic community. How satisfied are you with your community as a place to live?

It occurred very early in the survey before it was apparent that this was a survey of Mormons. And Mormons’ level of satisfaction with their community is high. It’s higher than the public overall, but it’s especially high among Mormons in Utah who live in areas where the greatest concentrations of Mormons are. So that would suggest that there might be a link between the number of Mormons one is surrounded by and one’s perceptions of what it’s like to be a Mormon in the United States. And I’ll leave it at that. Maybe Dave and Matt have some additional detail to share.

BOWMAN: Yes, I do. It’s worth noting, I think, to this question that Mormon congregations are formed geographically, and so Mormons go to church with people who live near them. I think this may have something to do with that sense of strong community and a strong local community in particular.

CAMPBELL: I don’t know whether I’m stepping outside the bounds of this conversation, but I can speak to other data where questions have been asked of not just Mormons, but Americans in general: Have you ever heard negative comments made about your religion? Mormons actually rank at the very top. Mormons and Jews are the two groups that are the most likely to say that they’ve heard something to their face said negatively about their religion. So at least some of what we’re picking up, I think, in this Pew survey regarding the negative perception that Mormons feel from the rest of America is actually a product of their personal experience, having heard comments that they perceive as being negative or critical or even hurtful.

LUGO: Very helpful, Dave. Absolutely feel free to bring any reliable data to bear on this conversation. We share the limelight with you; delighted to do it.

MICHELLE BEARDEN, THE TAMPA TRIBUNE: Yet another question that wasn’t addressed in the survey, so you might be able to have it from other data. But I was wondering if anybody knew about the single biggest factor as to why Americans consider Mormons a cult. I mean, that’s a pretty strong word, and so to consider someone a cult, is there a particular factor that stands out? And this is also part of that question: What are the beliefs that bother non-Mormons the most about Mormons? I’ll leave that to any of you to answer.

LUGO: Let’s begin with Greg, and let’s put the cult answer in context with what people were also saying because, again, the fact that it’s the most commonly given answer doesn’t mean that everybody answered, “a cult.” So put that in context for us, Greg.

SMITH: Sure. You’re exactly right to point out that when we talk about the words that people use that come from the top of their heads to describe Mormonism, “cult” is commonly offered in response to that question, but that doesn’t mean that anything like a majority volunteer that word because people can volunteer any word that they want. So you can imagine that there’s a wide variety of responses we get. We get other negative responses. Some people cite “polygamy.” But I should also say we get a very large number, as well, of positive responses.

I hope that our comments here today shouldn’t be taken to suggest that the American public as a whole is completely negative toward Mormonism. That’s not the case. There are many people who are quite favorably disposed toward Mormons. And a lot of the common answers that we get in response to this question, what’s the one word that comes to mind to best describe Mormonism, are positive: words like “family,” words like “family values,” words like “committed,” “dedicated,” “good people.” While I think it’s important to be cognizant of the reservations that many Americans do have, it’s also important to recognize the flipside as well.

The one other thing that jumps to my mind that might speak to this question is that in previous polling that we conducted, and I’m thinking back especially to some polling we did back in 2007, we tended to find a strong link between whether or not people view Mormonism as a Christian religion and their overall views of Mormons and Mormonism. Americans who say Mormonism is a Christian religion tend to have more favorable views of it, tend to be more likely to see it as similar to their own faith and so on. Americans who say Mormonism is not a Christian religion, by contrast, tend to be more negative. So that’s the thing that jumps to my mind that we’ve seen in our data in terms of people’s concern about Mormonism.

LUGO: Obviously we can’t test this because we can only ask people about their current attitudes, but in my own mind I do the counterfactual: What if Mormons did not view themselves as Christians, as the vast majority do, and say they were such? Would that make any difference, let’s say, among evangelicals and others with respect to their attitudes towards Mormonism if they felt that, look, it’s just a different religion?

I wonder if part of it — again, this is sheer speculation — may not be involved with the claim that the Mormon church makes to being Christian and then, particularly on the part of a certain segment of the Christian community, that rubbing them the wrong way, as it were. I’m just throwing that out there. Maybe David or Matt would like to add their thoughts on that.

CAMPBELL: Sure, I’ll weigh in. One thing I should note is this survey was done not long after the word “cult” was being associated with Mormonism in the news because of the statement made by Pastor Jeffress there in Dallas at the Values Voter Summit. That’s not to say that that word wouldn’t have come up otherwise if you did the survey at a different time, but that’s probably worth noting because other surveys are finding when you ask people, what word comes to mind when they hear “Mormon,” surveys done in the last couple of weeks — “polygamy” actually seems to rise to the top rather than “cult.”

Both of those are negative terms, and they probably have a lot to do with one another. I think when people are answering a question, what comes to mind when you hear the term “Mormon,” and they say “cult,” I doubt that they have a very precise definition in their mind of what a cult is. I think what they’re saying is that this is a religion that is different than mine and has some elements of it that I find objectionable.

I like Luis’s point; I think it’s an important one to make, that when we say that the concern over Mormonism is that it’s not Christian, that isn’t actually quite the whole story. It’s that it’s not Christian and claims to be Christian. That, I think, is what concerns evangelicals. And as to why it is that other groups, particularly evangelical Christians, take issue with Mormonism, I’m sure that a spokesperson for an evangelical denomination could give you a whole long list, but it would start with the fact that the Mormon faith, or the LDS faith, does believe in scripture beyond the Bible. That’s where the nickname “Mormon” comes from, the Book of Mormon.

Another one that I think rankles a lot of evangelicals is that Mormonism actually claims to be a restored form of pure Christianity, that Joseph Smith marked the beginning of a new era in Christianity, and that prior to Joseph Smith starting the LDS Church, all other Christian faiths had been corrupted and were not a representation of what Jesus himself organized on the earth. And so you can maybe appreciate why that would rankle at least some evangelicals and perhaps those in other Christian faiths as well.

LUGO: That’s true, and in fact, there’s another religious group that’s of similar size to Mormons, and that’s Jehovah’s Witnesses, who also make restorationist kinds of claims. They’re also not held in very high esteem by evangelicals.

ALAN COOPERMAN, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: I just wanted to note that we have asked this one-word question twice. We asked it the first time in 2007, and in 2007 the most common single response was “polygamy.” As Dave notes, it’s also been coming up more recently in other polls. The second-most common response in 2007 was “family.” This time around, when we asked in 2011, the single-most common response was “cult,” but other common responses were things like, also, “family” or “family values,” “dedicated,” ”devout,” “religious,” “friendly,” that sort of thing.

So I think what jumped out when you look at this open-ended question, in fact, is that the American public as a whole has a mixture of both positive and negative and some simply neutral — because conservative and Republican are also common associations — but some very positive, but also some very negative associations.

TIM TOWNSEND, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH: Hi. You mentioned in your opening remarks, Greg, about the tension between evangelicals or that Mormons feel from evangelicals. I just wondered if there were any other questions in the survey about how Mormons feel about what other religious groups feel toward them. I know that Professor Campbell has looked at this before, about how Jews or Catholics, for instance, feel toward Mormons. But I wondered if that was a part of the survey or if there were any findings about that.

SMITH: The one other question that I think taps into this — not directly, but I think indirectly — is the open-ended question we asked: What are the most important problems facing Mormons in the United States today? I think you can see in the responses to that question a reflection of Mormons’ ideas about how they’re perceived by other groups.

For example, 12 percent of the Mormons that we spoke with said one of the most important problems Mormons face is that they’re not seen as Christian. Another 7 percent say, we’re seen as a cult or as a sect. And another 7 percent say, we’re seen as polygamists. I think what you’re seeing reflected there is this recognition of some of the perceptions that non-Mormons have toward Mormons, perhaps especially evangelicals.

LUGO: Matt, why don’t you jump in on that?

BOWMAN: I was going to say something about the word “Christian” and another reason, in addition to Dave’s, why this would be a problem. Evangelicals do not think Mormons are Christian for two reasons. One is that Mormons believe that God the Father and Jesus Christ are two separate, physical beings, and many evangelicals hear this belief and conclude that Mormons do not believe that Jesus Christ is actually God.

Secondly, many evangelicals reserve the word “Christian” for people who have been saved — people who have had a conversion experience — and to Mormons, salvation does not work this way. So that may be not in direct response to the question asked, but it is what I had to say.

LUGO: All right. That’s very helpful. Thank you.

ANDREW LAWTON, LANDMARK REPORT: Good morning. It was said at the top of the call, I believe, this is the first study of its kind to not be done by LDS, and I was wondering if there were any discrepancies or disparities in the data in this survey and any that you know of that have been done by LDS — and if you could go over those, if they do exist.

LUGO: That would be for David and Matt, I think, to respond to.

COOPERMAN: Or even more, if I could jump in — Marie Cornwall, who was one of our advisers, was involved in at least one of the unpublished LDS surveys, and maybe more than one. She might be able to answer that. But since the results of those surveys have not been published, we were not able to include comparisons with them in our report.

LUGO: Marie Cornwall, one of the advisers Alan was mentioning, and if you want her contact information, we’d be delighted to give that to you.

CAMPBELL: One thing that I’ll mention is that we know the LDS Church does some research internally, although I don’t know how much of it actually would be comparable to what this survey reflects. Over the years, we’ve seen smaller surveys done of an LDS population in one part of the United States or maybe in another part of the world, and those are not, perhaps surprisingly, often done by LDS scholars themselves.

Then, of course, another source of data on Mormons has come from large surveys, Pew being one of the leading organizations on this, but there are other sources of data as well, where we’ll do a large survey of the entire U.S. population, and if it’s big enough, it means you can actually say something about smaller groups, like Mormons or Jews or Muslims.

If you take a look at all of that data put together, I wouldn’t say that there’s anything in this study that sort of leapt off the page at me as something that seemed surprising or shocking or completely out of line with what we’ve seen in other data. I would say that this study maybe deepens our understanding of Mormonism, but I don’t think it fundamentally alters it.

LUGO: Thank you. That’s very helpful. Matt, did you want to say anything? I know David is the numbers guy, the survey guy, but just in general in terms of Mormon self-perception, as you understand it, what would they find surprising in this survey? Or would they say, you know what? We’re looking at the mirror here.

BOWMAN: Yeah. I think, as Dave says, there is not much in this survey that would surprise many Mormons. One thing that may, I think, is something that Dave noted near the beginning and Greg did as well, that this survey because it is self-identified — practicing Mormons — it was probably not a mirror of your average Mormon congregation, which has fairly high rates of people who do not go to church, high rates of people who would not answer the questions about practice and belief with the same sort of unanimity that you see in the respondents here. But generally, I think, what you have here would actually make the Mormons fairly happy.

LUGO: Thank you so much to everybody — the journalists for listening in and participating, to David Campbell and Matt Bowman. If we can be of further help to you folks in writing your stories, please do not hesitate to call. We’re here to be of service to you. Again, thank you for joining us on this call. Our time, unfortunately, is up. Thanks so much.

This written transcript has been edited by Amy Stern for clarity, grammar and accuracy.