The Pew Forum’s Alan Cooperman and Greg Smith, along with Boston University professor and author Stephen Prothero and Krista Tippett of American Public Media, explore key findings from a new Pew Forum survey on how much Americans know about religion as part of a panel discussion at a national symposium on religious literacy in Washington, D.C. The symposium, which was held in conjunction with a screening of the upcoming PBS documentary series “God in America,” was coordinated by WGBH Television in Boston and the Religious Freedom Education Project at the Newseum.

Speakers:

Alan Cooperman, Associate Director for Research, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

Greg Smith, Senior Researcher, Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life

Stephen Prothero, Professor, Boston University

Krista Tippett, Host and Producer, “Being,” American Public Media

Moderator:

Ray Suarez, Senior Correspondent, PBS NewsHour

Navigate This Transcript:

Survey Questions Most Got Right

Knowledge of the Ten Commandments

Questions on Their Own Faith

Restrictions on Religion in Public Schools

Atheists and Agnostics Most Knowledgeable

Questions on World Religions

Education is the Leading Predictor

Why Religious Illiteracy Matters

Prothero: In my class, that’s a D

Looking at the South

Looking at Catholics

RAY SUAREZ, PBS NEWSHOUR: We’ll set the table for our first discussion – “U.S. Religious Knowledge” – with Alan Cooperman, the associate director for research at the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. Alan?

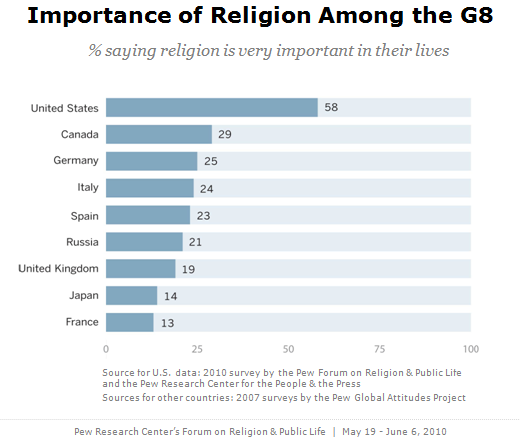

ALAN COOPERMAN, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: We know from our past surveys that the United States is a very religious country. Indeed, by some measures, it is the most religious of the world’s rich, industrial countries. Nearly six-in-ten Americans say religion is very important in their lives. That is double, roughly speaking, the percentage in any of the other G-8 countries.

But the question arises, how much do Americans actually know about religion? Three years ago, Professor Stephen Prothero, who’s here, wrote a best-selling book, in which he argued that Americans are both deeply religious and profoundly ignorant about religion. At the same time, Professor Prothero lamented that there really wasn’t much hard data available about this, and he noted that researchers – that would be us – had put a lot more effort into measuring Americans’ religious beliefs than they had into measuring Americans’ religious knowledge. So in short, three years ago, Steve threw down the gauntlet and we’re picking it up today.

Steve has been a great help in this project. We’re deeply grateful to him and to our other expert advisers – Marilyn Mellowes of WGBH and John Green of the University of Akron – as well as to our polling consultant, Mike Mokrzycki. We’ve got some very provocative, in the best sense of that word, results to discuss with you.

But before I do that, I want to acknowledge a couple of very important limitations. First of all, because this is a first-time effort – never done a survey like this before – we don’t have any historical data. So we do not try to say anything about whether Americans today are more or less knowledgeable about religion than previous generations of Americans. You can have speculation on that, but we just don’t know.

Second caveat is that we have deliberately abstained from grading the American public with an A, an F or anything in between. We feel we do not have any objective way of determining what the public should know about religion. So this survey is not like a college course that Steve or others might give, where a curriculum has been presented to the American public and now we can test how well the public has done. It’s not like that.

We cannot claim that the questions we asked are necessarily the most important things to know about religion. We do hope that they are not trivial. And we think that they are pretty good indicators of how much Americans know about religion. In total, the survey contained 32 questions designed to test Americans’ religious knowledge. I’m going to show you just a small sample.

Most of them were multiple-choice. About a third were about the Bible and Christianity. Another third or so were about world religions, including Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and religious geography. A third explored Americans’ knowledge about Mormonism, the meaning of terms such as atheist and agnostic, some historical issues in religion, and religion in public schools.

So let’s begin, just to give you an introduction to the questions, by starting with a few of the questions that most people got right. These are some of the questions most frequently answered correctly. At least two-thirds of the people surveyed – 3,412 people surveyed – at least two-thirds got these questions right. Eighty-five percent knew that an atheist is someone who does not believe in God. By the way, 7% confused that term with agnostic and said that an atheist is someone who is unsure whether God exists.

Eighty-two percent know that Mother Teresa was a Catholic. Three percent think she was Jewish. Seventy-two percent know that Moses, and not Job or Elijah or Abraham, led the Biblical exodus from Egypt. Seventy-one percent know that the Bible says Jesus was born in Bethlehem. By the way, a quarter thought he was born in Nazareth or Jerusalem.

About two-thirds of the public knows that the Constitution says that the government shall neither establish a religion nor interfere with the practice of religion. By the way, 18% think the Constitution does not say anything, one way or the other, about religion, and 3% think that the Constitution privileges Christianity. Sixty-eight percent know that most people in Pakistan are Muslim, and not Buddhist, Hindu or Christian.

Now here are some of the things that about half – roughly speaking – half the public gets right. To begin with, we asked a question where we gave four statements and we asked, which one is not among the Ten Commandments? Do not commit adultery. Do not steal. Keep the Sabbath holy. Or, do unto others as you would have them do unto you. A little more than half the public knows that the Golden Rule is not among the Ten Commandments. By the way, the most common wrong answer: Keep the Sabbath holy. More than a quarter of Americans think that “Keep the Sabbath holy” is not among the Ten Commandments and that “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” is.

Fifty-four percent correctly named the Koran when asked to name the Islamic holy book, and 52% know that Ramadan is the Islamic holy month and not the Jewish day of atonement or the Hindu festival of lights. Fifty-one percent know Joseph Smith was a Mormon. Nearly as many know that the Dalai Lama is a Buddhist. Also, almost half know the Jewish Sabbath begins on Friday. The largest single wrong answer to that question was Saturday, although a substantial number also said Sunday – 7% said Sunday; 18% said they didn’t know.

And a little less than half of the public can correctly name, in a non-multiple choice question, an open-ended question, the four Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Finally, here are some of the things that less than a third of the public gets right. Only about a quarter of Americans know that most of the people in the largest Muslim-majority country in the world – Indonesia – are Muslim.

Only about one-in-five people understand sola fide – that Protestants and not Catholics teach that salvation comes through faith alone. By the way, 38% attribute this teaching both to Catholicism and to Protestantism. So not too great an understanding of the Reformation here. Jonathan Edwards – only about one-in-ten Americans can identify Jonathan Edwards as a preacher who participated in the first Great Awakening. Twenty-eight percent named Billy Graham. Billy Graham is old, by the way, but he wasn’t around in 1740. (Laughter)

Now, I’m not sure whether what you’ve seen thus far strikes you as pretty good, pretty terrible. As I said, we abstained from giving the public an A or an F or anything else, and we feel that we have no way, really, of saying whether Americans know more or less about religion than they do about physics or history or geography or politics or sports. But I do think that it’s fair, in particular, to ask how well people do on basic questions about their own faiths.

The survey finds, not surprisingly, that on specific questions about specific faiths, members of those faiths generally do better than the rest of the public. But on the other hand, we do find that large numbers of Americans are not well-informed about some of the major tenets, practices and history of their own faith tradition. So let’s go through some of those.

For example, we asked, which of the following statements best describes the Catholic Church’s teaching about the bread and wine used for communion? Do the bread and wine actually become the body and blood of Christ or does the church teach that the bread and wine are just symbolic of the body and blood of Christ?

Now, of the general public, more than half get this question wrong; just 40% get it right. Catholics do substantially – maybe I should say trans-substantially (laughter) – better: 55% of Catholics know that their church teaches that during communion, the bread and wine actually become the real presence of the body and blood of Christ. And Catholics who go to Mass regularly do even better. But still, this question shows that almost half of Catholics do not understand, are not familiar with the church’s teaching on the Eucharist.

Judaism – my people. We also asked, would you tell me if Maimonides was Catholic, Jewish, Buddhist, Mormon or Hindu? Again, what was the faith of Maimonides? Less than one-in-ten Americans know that Maimonides was a Jew. By the way, one wonders what this would be if there weren’t 25 medical centers named for him. (Laughter.) Jews do a lot better on this question – 57% of Jews get this right. But still, more than four-in-ten Jews in America apparently do not recognize the name and faith of the most venerated rabbi and Torah sage in history.

Protestantism – we asked the name of the person whose writings and actions inspired the Protestant Reformation. Was it Thomas Aquinas, John Wesley or Martin Luther? Three possibilities on this one. Like the general public, fewer than half of Protestants said Luther. A third of Protestants, by the way, said they didn’t know, and 15% incorrectly named an 18th-century theologian, John Wesley. The Protestants who attend services weekly or more did somewhat better. Still, it’s fewer than half of Protestants in the United States who can identify Martin Luther.

This is a tough question, in some respects: Which religious group traditionally teaches that salvation comes through faith alone? About one-in-five Americans correctly answers Protestantism. Protestants themselves do a little bit better, and Protestants who are frequent churchgoers do considerably better. But still, as you see, the vast majority of American Protestants apparently do not recognize sola fide, one of the key theological distinctions between Protestantism and Catholicism.

The survey also included three questions about restrictions on religion in public schools. Of all the questions in our survey, the single question that the highest percentage of people got right was, according to Supreme Court rulings – not your own opinion – according to Supreme Court rulings, is a public school teacher allowed to lead a class in prayer?

Nearly nine out of 10 Americans correctly said no. At the same time, however, one of the questions most often answered incorrectly was whether it is permissible, according to Supreme Court rulings, for public school teachers to read from the Bible as an example of literature. Only 23% of those surveyed know that this is permitted. It’s explicitly permitted by the Supreme Court. Similarly, most people don’t realize that public school teachers can, and in fact do, offer courses comparing the world’s major religions. Only 36% get this correct.

Together, this block of questions suggests to us that many people think that the restrictions on teaching religion in the public schools are stricter than, in reality, they are. Now, I haven’t covered the entire survey by any means, but these are some of the highlights. And as I mentioned at the outset – and we do need to be humble about this – we cannot pretend that these questions necessarily reflect the most important things to know about religion.

And we know that we could have made up harder questions or easier questions, but what we can say with some confidence, and even delight, is that the questions we chose did a very good job of differentiating levels of knowledge among U.S. adults because, through a combination of good design and good luck, the overall results are an almost perfect Bell curve.

Of 3,412 people surveyed nationally, only eight people – they’re probably all here in this room – only eight people got all 32 answers right. And only six people got all 32 questions wrong. Now, the person largely responsible for that is my colleague, Greg Smith, the head of our survey data team. I’ll turn the mike over to Greg to dig more deeply into these results. (Applause.)

GREG SMITH, PEW FORUM ON RELIGION & PUBLIC LIFE: Good morning. Thank you, Alan. It’s a great pleasure to be here. It’s very exciting to be able to share the findings from this survey with all of you. I’d like to pick up where Alan left off, by considering the survey’s findings, as to the patterns in religious knowledge.

Who knows the most about religion and who knows the least? As has been alluded to, the groups that do best on our survey are atheists and agnostics, Jews and Mormons. Out of the 32 questions that we asked, atheists and agnostics answered an average of 20.9 questions correctly. Jews answered 20.5 questions correctly, on average. And Mormons got 20.3 questions right, on average.

These three top scores are followed by white evangelical Protestants, who answered an average of 17.6 of the survey’s 32 questions correctly. White Catholics and white mainline Protestants each answered about 16 – about half – of our questions right. And those who describe their religion as just “nothing in particular” got a little bit more than 15 questions right. Black Protestants answered 13.4 questions right, on average, and Hispanic Catholics – 11.6.

I think it’s fair to say that my colleagues and I, and probably many of you, have been struck by the strong performance of atheists and agnostics on this survey. What might explain their relatively high levels of religious knowledge? I have to say that our data don’t speak directly to this question, but we do know, as I’ll discuss in just a few minutes, that their strong performance is not nearly a function of their higher-than-average levels of educational attainment.

We think, though, that their relatively high levels of religious knowledge may reflect a fair amount of thought and consideration given to religion by people who describe themselves as atheist or agnostic. These are folks who have chosen to identify with a relatively small – they make up about 4% of the U.S. population – and a relatively unpopular portion of the U.S. population. We know that very few people were raised as atheists or agnostics. Indeed, our data show that about three-quarters of atheists and agnostics say that they were raised as Christians.

So the very fact that people identify themselves as atheist or agnostic may indicate that they’ve taken a side, so to speak, in the American religious discussion. Their very identification as atheist or agnostic may reflect that they’ve considered and given considerable thought to these matters, and that might be reflected in their high scores.

Another way that you can see this in our data is by comparing atheists and agnostics to those who describe their religion simply as “nothing in particular.” Atheists and agnostics are among the very top scorers on our survey, whereas those who describe their faith simply as “nothing in particular” performed below the national average. So it’s not simply the absence of a connection to a religious group that’s associated with higher knowledge; instead, it’s the presence of this self-identification as an atheist or agnostic. We think that those things might have something to do with this puzzle.

Digging into the data a little bit more deeply, we see that the realm of religious knowledge in which atheists and agnostics and Jews really excel is on the questions that we asked about world religions other than Christianity, including Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and Judaism.

Out of 11 questions in this area, Jews answered an average of 7.9 correctly, and atheists and agnostics answered 7.5 correctly, on average. You can see here that no other group really comes close in this area. Mormons, the next-highest scoring group, get an average of two fewer questions right, out of only 11, compared with atheists and agnostics. White evangelical Protestants, white mainline Protestants and white Catholics all answered fewer than half of the survey’s 11 questions about world religions correctly.

We see a very different pattern on the survey’s 12 questions about the Bible and Christianity. Here, Mormons do best, with 7.9 out of 12 questions answered correctly, on average. And they’re closely followed by white evangelical Protestants. Atheists and agnostics and Jews also get more than half of the Bible and Christianity questions right, but they’re not the very best performers in this area, as they are in so many of the other areas we looked at in the survey.

Notice, too, that Black Protestants do better on questions about the Bible and Christianity, relative to other groups, than they do on the full set of 32 religious knowledge items. Black Protestants, white mainline Protestants and white Catholics each answer about a half of the survey’s Bible and Christianity questions correctly, on average.

Now, what are the factors that help to contribute to overall levels of religious knowledge? The survey shows that the No. 1 predictor of how people did on the religious knowledge questions is educational attainment. College graduates get an average of 20.6 of the questions right – about two-thirds of our total of 32 questions. Those with post-graduate training or post-graduate degrees, who get more than 22 questions right, on average, do even better than those with bachelor’s degrees, who get an average of 19.8 questions right. Those people with some college education but no four-year degree get 17-and-a-half questions right, on average. And those with a high-school education or less get about 13 questions – about 40% of the total – right.

You can also see that those people with post-graduate training get about twice as many religious knowledge questions right, compared with those who have not completed high school. So educational attainment is a very powerful predictor. It’s, without question, the most powerful factor we examined in shaping people’s overall levels of religious knowledge.

The survey also shows that, beyond overall levels of educational attainment, specific kinds of educational experiences are linked with religious knowledge. The survey asked people who had been to college whether or not they took a religion course while they were there. Those who say they did take a religion course in college answered an average of 22.1 questions right, significantly higher than the 17.9 among people who did go to college but did not take a religion course while they were there.

The survey also asked people what kinds of schools they attended as children – public or private – and it asked those who’d been to private school whether they’d gone to a religious private school or a non-religious private school. Now, perhaps as you’d expect, those who attended private school did better on the religious knowledge questions than those who attended public schools, by more than two questions, on average. However, the survey also shows, interestingly, I think, that among those who attended private school, there is no significant difference between those who went to a religious private school and those who attended a secular private school.

Let me also point out one other thing that we really tried to do with this project. In this report, we really wanted to dig below the surface and try to answer the question of what kinds of traits are strongly associated with religious knowledge and which traits seem to be linked with religious knowledge but, in reality, are only tangentially linked, if at all.

In other words, do atheists and agnostics, Jews and Mormons outperform other groups in our survey because they’re more educated than members of most religious groups or because they have other traits that are linked with higher levels of religious knowledge? Or is it the case that atheists, agnostics, Jews and Mormons are more knowledgeable than evangelicals, mainline Protestants and Catholics, even after education and other factors are taken into account?

To try to address these kinds of questions, we used a technique called multiple regression analysis. We began with a statistical model that includes a variety of religious and demographic variables, like education, age, gender and race. And it considers the impact of each one of these one at a time, while holding all of the others constant. This produces a picture of how much each factor contributes to religious knowledge, independent of all of the other variables we looked at.

This analysis confirms that educational attainment is, far and away, the single leading predictor of higher religious knowledge, even when you take other things into account. It also shows that men score a little bit better than women, by about 1.4 questions, on average. It shows that whites score better on the religious knowledge test than Blacks and Hispanics. It shows that people who live outside the South do better on our survey than Southerners by about one question, on average. And it shows that the oldest group in the population gets about one fewer question right compared with younger age cohorts.

These analyses also show – and this is probably the most interesting finding of the survey from my perspective. These analyses also show, as I alluded to earlier, that the strong performance on these questions by atheists and agnostics, Jews and Mormons is not simply attributable to their educational background or to other of their demographic characteristics. Instead, even after all of these other factors, including education, are taken into account, atheists and agnostics, Jews and Mormons still outperform all other religious groups in our survey.

These three top performers are followed by evangelical Protestants, who, in turn, score better than mainline Protestants, Catholics and those who describe their religion simply as “nothing in particular.” I should also point out, though, that even though atheists and agnostics are among the best performers on the survey, if we look at the population overall, it turns out that people with the highest levels of religious commitment – those who say that they attend religious services regularly and that religion is very important in their lives. Those with the highest levels of religious commitment do a little bit better on the survey compared with those with medium or low levels of religious commitment.

Now, this might seem contradictory. How can atheists and agnostics be among the top performers on the survey if those with low levels of religious commitment do worse than those with the highest levels of religious commitment? What we have to remember is that atheists and agnostics make up only a small portion of people, even a small portion of people with low levels of religious commitment. There are lots of people in the low- and medium-religious-commitment categories, in other words, who are not themselves atheist or agnostic and who don’t do as well on the religious knowledge questions.

So these are some of the highlights of our survey, some of the highlights of our analysis. Atheists and agnostics, Jews and Mormons do best on religious knowledge questions overall. Large numbers of people are unfamiliar even with important aspects of their own faiths. And the public thinks that there are more restrictions on religion in the public schools than is actually the case.

Let me also point out one great new feature that accompanies this project: With this report, we are entering the world of online quizzes. You can go to our website and complete a selection of the survey’s questions for yourselves, and you can also see there how your results compare to those for the public overall, as well as to a variety of religious and demographic groups. So with that, I thank you for your attention. I look forward to discussing these findings further. And I will yield the floor.

SUAREZ: Joining Gregory Smith, whom you just heard from, and Alan Cooperman, are the rest of our panel: Stephen Prothero, author of Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know – and Doesn’t, and a professor of religion at Boston University, and Krista Tippett, host of “Being” on American Public Media, and the author of Speaking of Faith: Why Religion Matters and How to Talk About It, which is a pretty useful thing for the purposes of this morning’s conversation.

At the risk of sounding dismissive, Stephen Prothero, so what? Beyond being able to do well if “Jeopardy” is on in the room while you’re doing something else, beyond walking into a church on your travels and, even if you’re not Catholic, seeing a monstrance on the altar and knowing what it is, so what?

You had to commute. You had to put your pants on in the morning. You had to get yourself three meals. You had to worry, perhaps, about other people and whether they were getting their three meals. This, depending on how you look at the numbers, that base of knowledge or lack of knowledge means what to 306 million people’s daily lives?

STEPHEN PROTHERO, BOSTON UNIVERSITY: Well, I think the level of religious education inside these religious communities is very important to each of them. So if you talk to rabbis, they’re concerned about Jewish illiteracy. If you talk to Catholic priests and nuns, they’re concerned about Catholic illiteracy. If you talk to evangelical Christians, they’re concerned about biblical illiteracy in their ranks.

But the focus of my own writing on this question has been more about the political and civic side. And I think there are two ways in which religious illiteracy matters. One is domestic and one is international.

On the domestic side, we have, now, two religious political parties. We used to have one, until maybe six years ago, or maybe four or maybe two, depending on how you count. But we now have both parties that are trying to link their particular public policy initiatives to the Bible and to Christianity in particular, and then, more broadly, to religion.

So without an understanding of Christianity and the Bible, the American public is handicapped in terms of evaluating whether it makes sense, for example, when Hillary Clinton says that Republican initiatives about immigration violate the Good Samaritan story. That’s not a claim we can evaluate if we don’t know what the Good Samaritan story is. Similarly, we can’t evaluate claims of people who say, I’m a Christian and I’m opposed to abortion because the Bible is opposed to abortion, if we don’t know anything about the Bible or we wouldn’t know where to look in the Bible to look for the question of abortion.

The more important issue, though, to me, is international. The question is, how can Americans understand the world, act in it economically, politically and militarily, without knowing something about the world’s religions? We’re having a conversation in the United States, or trying to, about Islam. Someone’s trying to burn Korans and half the American public doesn’t know that the Koran is a scripture in Islam, according to this survey – 46 or 48%, or something like that.

We’re looking for moderate Islam. That’s been in the conversation since 9/11. Where are the moderates? Well, hundreds of millions of them are in Indonesia, but three-quarters of Americans don’t know that Indonesia is a Muslim-majority country and we wouldn’t know to look there because we don’t know that Islam is active there. So yes, there is a kind of “Jeopardy” quality to this. I think it’s very easy to look at a particular question and dismiss it and say, well, what does that really indicate?

But I think these kind of simple questions indicate the deficit that we have, as a country, in understanding the religions of the world and our own religions, and it handicaps us to act as informed citizens, as we’re supposed to in the democracy that we live in. So I think it matters a lot and I think the answers to the “so what” question are many and various, but those are at least two.

SUAREZ: Well, you used the phrase, “what it indicates,” and what if it indicates nothing but a set of habits of mind? Krista, I was not surprised at all when the survey results showed that atheists knew an awful lot about religion because, just as a practical matter, they know what they have to argue against, and they know what they’re leaving.

And when you hear that three-quarters of all atheists were once Christians, you know, good job, Sunday school teachers – (laughter) – because something obviously didn’t stick. But it may show nothing more than a way of being immersed in our common world. I mean, New Yorkers know when it’s Yom Kippur because they don’t have to pay parking meters, apart from those who have a confessional allegiance to it.

So if you are the kind of person who’s just alive to the world around you, you’re more likely to be picking up things that really have nothing to do with you on a daily basis, but it makes life more interesting. Surely, as someone who’s talking to people about how to talk – you’re talking to people about how to talk about it. Well –

KRISTA TIPPETT, AMERICAN PUBLIC MEDIA: So what you’re pointing at is that religious experience is bigger than beliefs and bigger than knowledge, right? It’s practice; it’s experience; it’s ritual; it’s community. And people may not be able to turn that into correct answers or incorrect answers. I guess I think you’re right, atheists and agnostics may know what they’re rejecting. I also think the breakdown – what is the breakdown? It’s a small percentage point of atheists and a larger percentage point of agnostics, right, isn’t it? More people say they’re agnostic or unaffiliated – many more.

SMITH: A few more.

TIPPETT: OK, OK.

SMITH: It’s 4% total, and then each, roughly 2%, but there are a few more – atheists, a little below 2; agnostics a little above 2. But it’s not a huge difference.

TIPPETT: I’ll just say, experientially, starting a program on public radio called “Speaking of Faith” – we recently have changed the name – but we have become aware, over these seven years, that we have a huge number of atheists and agnostics who are some of our most engaged listeners.

So I experience, I would say, atheists and agnostics to be some of the most ethically engaged people in our culture. And I would even say, although some of them might bristle at this language, to be some of the most energized spiritual seekers. So that’s a dynamic here, too. Something I’m also aware of, having grown up in the Bible Belt going to church three times a week, I would have utterly failed. I would have been one of those six people.

SUAREZ: Oh, come on!

TIPPETT: No, really! I wouldn’t have learned any of this. It was about living in a culture, OK? It wasn’t about a base of knowledge. Intellectual curiosity was not encouraged. And this gets at the question that’s raised for me so much – not the “so what” question, but, so what’s the source of the problem and how do we talk about a solution? I don’t think intellectual curiosity is encouraged inside many traditions and many religious communities.

SUAREZ: No, but I’m interested in your use of that phrase “source of the problem” because it presumes that this is a problem, when the high level of correlation with education may simply mean that people who are more likely to know the answers to these questions are more likely to know a lot of things that people who have less education are less likely to know about.

PROTHERO: Yes, but let’s not forget, though, that two-thirds of the people who go to college and are scoring high, along with the agnostics and atheists, they’re only getting 66%. And I know that you all aren’t going to grade it, but I will because I’m not an employee of Pew. (Laughter.) And that’s a D, you know?–

SUAREZ: But Americans only grade on a curve.

PROTHERO: So I mean, the atheists and the agnostics, if they’re in my class, that’s a D and the average American is getting an F. So it’s not like this is something so great to write home about. Yes, you can talk about the relative performance, but in terms of absolute performance, it’s pretty sad. I mean, we did not ask whether the Pope was Catholic. I was sort of keen to ask a question like that, just to show.

But we did ask, is the Dalai Lama Buddhist, and to me, that’s pretty close to, is the Pope Catholic? But half of Americans don’t know that the Dalai Lama is Buddhist. How do you have a conversation about Tibet if you’ve never even heard of this guy? It’s like having a conversation about Vatican City without having heard of that guy. It’s a difficult thing to do.

SUAREZ: But probably, the same –– it’s many of the same people who can’t find Iraq on a map when we’ve got 150,000 troops fighting there. So maybe the question is broader than religious knowledge but implicates religious knowledge because we’ve asked discretely about this area of our shared experience and shown that people aren’t really paying that much attention.

PROTHERO: But I think it’s important to remember, too, though, on these questions about religion in the public schools, that we have an erroneous public perception that we’re not allowed to teach about the Bible or the world’s religions in the public schools. Between three-quarters and two-thirds of Americans, on those questions, think that this is not a topic that can be broached in public schools. We don’t have that perception about geography, for example.

We know we’re allowed to teach where Iraq is on a map. We think we’re not allowed to teach what Christians believe. We think we’re not allowed to teach what the Five Pillars of Islam are. So this, to me, is the great catch-22 in the survey, that we have this religious illiteracy in the public but the illiteracy is so huge that we think we’re not allowed to remedy it in the public schools.

But it’s very, very clear, from what the Supreme Court has said about religion in public education – and there’s, I think, one quote in the report – that no, you cannot pray with your teacher; no, you cannot read the Bible devotionally; but yes, you can teach the Bible as literature and yes, you can teach the world’s religions. And the Supreme Court justices don’t just say that this is constitutionally kosher; they also say that we should do it – that you’re not an educated person unless you know something about the Bible and you’re not an educated person unless you know something about the world’s religions.

But this message is not getting out to school administrators. It’s not getting out to public school teachers. And I think that it’s different from other arenas where we have a deficit, like science and geography, in that we actually believe, wrongly, that we can’t teach it in public schools.

SUAREZ: But if the current elbows-out wrestling in the public sphere is as content-free as it tends to be, it has to do with self-representation rather than actual underpinnings of what this is all about.

When they have a fight in the Kansas City Zoo over whether you can put a statue of Ganesh at the elephant house because Christians rush in, complain to the authorities that oversee the public parks in Kansas City and say, you must have Noah’s Ark there as well or else you’re making a gesture that is biased toward Hindus in a city – and this is no knock at Kansas City – but I doubt one-in-100 people could explain what Hindus believe or their creation story or their pantheon, or very much about Hinduism at all, but Ganesh is perceived as a threat by the elephant house.

We’re in a period in our shared life here in this country where everybody’s very vehement about religion, but in a kind of content-free manner. I don’t know how you pull up your socks from that kind of posture. What’s the next thing to do, Alan? I mean, what’s the project, at this point?

COOPERMAN: Well, I am an employee of Pew. (Laughter.) We are agnostic – almost atheist – about policy prescriptions. Some of this conversation, though, has led me to think that there might be interest in how the public does on general knowledge questions. We did have a few of those in the survey. ––We don’t really have a way, again, to say whether people know more about Christianity than they know about chemistry, or vice versa. And on, essentially, a 20-minute telephone survey, we can only ask so many questions. But we did ask nine general knowledge questions for comparison purposes.

So 59% of the public knows that – who is it – Joe Biden is vice president. The same percentage – six-in-ten – know that antibiotics don’t kill viruses. Susan B. Anthony stunned us; she’s on top of the charts here. I mean, people really get the Susan B. – I don’t know whether it’s the dollar coins that no one uses, or – (laughter). Forty-two percent know that Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick. By the way, 4% believe it was Stephen King.

And in an interesting comparison, to get to Ray’s general point, yes, those who do well on the religion questions do well on the general knowledge questions, and those who do poorly on the general knowledge questions do poorly on the religion questions. They do go hand-in-hand. And maybe Greg can give more of an analysis than that.

SMITH: The one thing I would add, in terms of the elbows-out approach and whether or not it’s content-free, I mean, I think we should keep a couple things in mind. One is that the survey clearly demonstrates that when it comes to religion, there’s an awful lot of important stuff that people are unfamiliar with.

But at the same time, the survey also shows that it’s not like the public knows nothing, either. People tend to be more knowledgeable, in particular, about their own faiths, as you’d expect. Eight-in-ten Mormons get all three of our questions about Mormonism right. Most Americans – I realize that this would warrant an F in a class – but most Americans get more than half of the questions we asked about the Bible right.

Seven-in-ten people recognized Moses as the one who led the exodus from Egypt. Seven-in-ten people can tell you where Jesus was born. I mean, these are important things about people’s own faiths that they are aware of. So I wouldn’t quite describe it as content-free, in terms of knowledge.

The other thing we should keep in mind is that it’s also not content-free in terms of beliefs. Even though people –clearly are not –experts in religious studies, it doesn’t mean that they don’t have deeply held beliefs, that they aren’t deeply engaged in their faiths, that they aren’t pious practitioners of their faiths. In many ways, there probably are some parallels with politics.

We probably don’t have a lot of people who are experts in the workings of American government, but it doesn’t mean that they don’t hold their ideological beliefs or their party identification very deeply. So I think there are two kinds of content that we have to keep in mind here: knowledge, but also depth of belief and practice.

SUAREZ: Well, let me amend that and say largely content-free. During the time of some of the highest-volume conflict about the posting of the Ten Commandments in civic buildings, it was found that a distressingly high number of Americans – and I say that out of a conviction that this is part of our common, Western cultural deposit – you should know what’s in it even if you’re not a believer – a distressingly high percentage couldn’t name the Ten Commandments, even if you said, don’t worry, you can say them out of order.

So here they were, ready to go to the barricades over posting the Ten Commandments in civic spaces, insisting on their right to be there, in many cases insisting on the primacy of Christianity in our civic life, and yet were making, not a content-free assertion, but let’s say, a content-handicapped assertion because they, themselves, could not even stand up for this Decalogue that they insist is a foundation stone of the United States. And I guess that gets to your point, Stephen, about when this is important and when it’s not.

PROTHERO: I remember there was a survey done in the ’60s where people were asked about the Ten Commandments. It was one of the few places where there were knowledge surveys before. But the question was, do you know the Ten Commandments? And the answer was, yes or no. So people were able to just say, oh yeah, I know the Ten Commandments. So it was a very different kind of survey.

But I think, for me, if you want to talk about the religion that everybody wants to talk about now, which is Islam, it seems since 9/11, we’ve been struggling to have a national conversation about Islam and we’ve been failing to have the national conversation. We have people who say, Islam is a religion of peace, and we have people who say, Islam is a religion of war. And then we have a rebuttal that says, Islam is a religion of peace. And then there’s a rebuttal to that, that says, Islam is a religion of war. And then there’s a rebuttal to that, that says, Islam is a religion of peace.

And that’s basically all we’re able to say. The question is, why? The answer, I think, as this survey helps to point out,– is because we don’t know enough to have a conversation. So we are then launched into your point exactly, which is the assertion of identity, right? I’m a Christian; they’re Muslims, right? And so we can’t have a conversation about, for example, Jesus in the Koran – Jesus appearing a hundred times in the Koran. Because we don’t even know that the Koran is the holy book of Islam, or at least, only half of us do. We haven’t read it enough to know that Jesus is in there.

So what happens, in terms of interfaith conversation and civic conversation about religion, is simply the assertion of identity. I think that if we had more knowledge about the world’s religions, we could actually have conversations, whereas right now we can’t have them. I think that’s to the great detriment of our public and civic life, that we can’t have a conversation about Islam, and so we see what is happening at the Islamic community center at ground zero. It isn’t a conversation. It’s a sort of assertion of, this is me and you’re not me and therefore, go away.

TIPPETT: I know you’re not saying that knowledge alone suffices, but I also think that a larger issue is not having a better cerebral knowledge of Islam, but knowing Muslims, right? It’s that personal relationship. It’s faces. And this is where the limits of something like this come in, although it’s incredibly valuable.

One thing I think that’s gone wrong with religion in America is how we have taken on – we, journalists, media, politicians –talk about religious people as sets of beliefs, and we define religions in terms of beliefs. You know, in fact, Muslims don’t really talk about beliefs, right? It’s about when you pray. It’s about how you live. It’s daily-lived piety. Buddhists don’t really have beliefs. Hindus don’t really have beliefs. So to me, it’s a combination of knowledge and that human component.

I actually think the thing that makes me most hopeful about all of this is a generational difference. Because what I see the young doing – I hate to generalize, even about generations – is engaging in relationships, engaging in service projects and then learning through that, building their knowledge base out of that, even starting to think theologically with more rigor about their own traditions out of that kind of contact.

SUAREZ: I’m wondering whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing that religion is one of those parts of our national life where everyone’s qualified to speak. If we were doing a segment on quarks on the NewsHour, no offense, Stephen, but we wouldn’t invite you–– because we’re assuming that there are probably better guys on quarks. But everybody can have an opinion on religion, whether they know anything or not.

And so it’s one of the hallmarks of the current – I mean, I don’t want to dignify it by calling it a debate – but the debate over Islam is – it’s like confetti being thrown into the air – people just saying stuff, and whether it’s grounded in 1400 years of the history of this religion or not remains to be seen.

PROTHERO: This is where, I think, the interpersonal point that Krista’s pointing out is really important. Because if you hear from Franklin Graham, for example, that what Muslims want is to kill Christians and Jews whenever they see them and you actually have a classmate in your high school, or a neighbor in your neighborhood, who’s a Muslim, you know that there is at least one Muslim that isn’t trying to kill all the Christians and Jews.

So I mean, I think that’s important. I totally agree, by the way, about the issue that religion is not about belief, or even necessarily about faith. I make this point in my latest book, that we shouldn’t even refer to religions as faiths because that gives too much ground to the Protestants, who think that religion is about faith – although now we’re not so sure, based on the survey, whether that’s true anymore. (Laughter.)

But to be fair, in this survey there are questions about things like Ramadan, which isn’t about a belief. It’s about a practice, right? So there’s a question about whether Americans know something about other people’s practices, or when the Sabbath starts, and things like that. But I also think that story is important, and that’s another thing that we tried to get at in the survey by asking about figures in stories, like Job or like – who else was asked – Moses, right?

So anyway, I’m totally agreed that religions are not belief systems, purely, and that there’s a sort of category mistake if you go there, and that one way we really do learn about other religions is through friends and neighbors who can tell us something about them.

SUAREZ: One of the interesting developments, Alan and Greg, in polling is deliberative polling, where you try to take a pool of people and see if they modify their views over time when you tell them more about something that you’re asking them about.

I wonder if questions about religion, because of where the answers reside in our personalities, would change that much over time if we told people more about these things and then asked them again in two months, a year, two years, or whatever. As people who are in this game, do you find this a useful exercise and could it be applied to this set of ideas and questions?

COOPERMAN: Well, we don’t do much in the way of deliberative polling. That is a part of our polling ethos, is that we try not to supply information that we know is going to affect the answer because we’re just getting the answer in one sense that, in another, we’ve supplied. We actually believe in fairly clean polling. Pew is not one of the places that does long introductions.

You know that in Congress a bill that would do this and that and the other thing is now under consideration; what do you think about it? We tend not to do that. We tend to ask, do you know whether this bill is under consideration, a bill about X, and do you follow it closely or not closely? And then we ask the follow-up questions. But I would just say that on the point about whether knowledge accretes to understanding, I don’t know.

Back in a previous life, to keep up my Russian, I used to lead tours in the Soviet Union during the Cold War. And some of the people that I brought to the Soviet Union – everybody learned a great deal – some came away more adamantly anti-Soviet and some came away less. Not by any means was everybody less, at the end of the day. But we do see in our data that there is a correlation between knowledge, or more broadly, familiarity, and positive attitudes about other things.

So we have asked this question about the Koran and a question about Allah – oh yes, thank you – what is the Islamic name for God? And we also asked, do you happen to know a Muslim? And people who know Muslims, people who know the word “Allah,” and people who know that the Koran is a holy book do tend to have more positive views of Islam than those who do not.

Similarly, it’s almost a truism in polling: People who say they personally know someone who is gay/lesbian/etc. are going to have more positive attitudes. Someone who says they know a Catholic or Jew or etc. will have more positive attitudes. So that familiarity, I would say, more than knowledge is what we can directly correlate with more positive attitudes.

SUAREZ: Well, let me turn that around, then, and ask Stephen and Krista whether, in the face of more and better information, people would even take onboard more, so that they’d have a different result. I think there’s plenty of evidence to demonstrate that even when you tell people something in this sort of free-fire zone of knowledge in the United States, they won’t necessarily take it onboard. They’ll just continue to assert what they’ve been asserting all along, like, don’t confuse me with facts, kind of thing.

So I’m wondering how malleable these results are by doing better in supplying knowledge, supplying facts, or whether, if you’re predisposed to have certain views about certain other Americans, you’re going to have them, even if you supply more information and say, no, no, no, not a religion of war, not full of murderous hate for believers of other religions, that kind of thing.

TIPPETT: One thing that, again, with the younger generations – there are many religious leaders who are understandably bemoaning the fact that people are not being raised in their traditions and they’re not staying in their traditions.– Pew’s done a lot of work on that. But I think a flipside of that is that people who are 18, 19, 20 don’t have the baggage that their parents had or that their grandparents had. They’re not rejecting anything.

I hear a lot of stories – and maybe you could speak to this – about undergraduates coming to college, about classes in New Testament and Hebrew Bible filling up with this open-minded, open-hearted curiosity, just wanting to know. Is that also an experience you have?

PROTHERO: Yeah, I think so. I think especially in the last 10 years there’s been a real interest of undergrads in courses on religion. I think that one thing that does happen, though, is, there’s a real quest for, kind of, big questions that goes on, on college campuses. And I think there is a redirection sometime in these courses toward facts and things like that, and that students are sort of like, well, wait a minute, I thought I was going to figure out my purpose in life, but instead, I’m being told whether Matthew was written before Luke and how much of Luke was stolen from Mark, and that wasn’t what I was here for.

But I don’t know. I guess it’s an institutional malady of college professors that we do tend to be hopeful about – maybe it’s true if NPR hosts – we’re hopeful about young people. So I’ll continue to be hopeful as well.

SUAREZ: I was interested in the South/not-South data because the South is, by its own self-reporting, the most congregationally affiliated, the most likely to answer religion “very important” in their lives, the highest levels of people who say they believe in God, and so on. Yet, this quadrant of the country is also the place with the lowest per-capita incomes, the lowest education levels, and also, now at the front lines of this question because so many Muslim students have come out of the countries of the world that will send them to the United States to learn to be engineers and doctors and various other things.

One-third of all the doctors in the rural South were born in South Asia, which sort of troubles the waters of racial hierarchies in a nice, fundamental way when the gentleman telling you to take off your clothes and put on this paper gown is of a different race from yourself. What can you tell us about what’s going on in the South, Greg?

SMITH: It’s very interesting. As we covered in the presentation, if you look at the results overall, the South is the region that really stands out. And it stands out because people in the South don’t score as well as people in the other regions of the country. People in the East and the Midwest and the West, they all do about the same as each other, and they all do a little bit better than people in the South.

I should also point out, though, something that gets back to this dichotomy, as to knowing about one’s own faith versus other faiths. If we restrict the analysis and we look only at questions about the Bible and about Christianity, then the South doesn’t come out at the bottom. Now, people in the South don’t do better than people in other regions about the Bible and about Christianity.

Perhaps you’d hypothesize that the Bible Belt would do better on questions about the Bible. They don’t. They do about the same as people in the Northeast and about the same as people in the West. The people in the Midwest actually do slightly better than people in the South, even on questions about Bible and Christianity.

But I do think that, that’s something that’s important to keep in mind. –I think it’s very helpful to look at the overall findings. We designed the survey specifically to try to get a good read both on what people know about their own faiths, as well as what they know about other faiths.

But we should also keep in mind that if you drill down a little bit and look at different domains, then the patterns can change a little bit, and that’s one of the things you see going on with the South. They don’t necessarily know less about their own faith, but they don’t score as well on questions about world religions and other faiths.

SUAREZ: This, of all the regions in the country, has been a hotbed of state-level battles over curriculum, over content, over symbolic displays of religious symbols in civic space – a lot of these wrestling matches over the place of religion in our common life. The South has been the locus of a lot of these battles.

PROTHERO: Yeah, there are now efforts in Texas to get mentions of Islam out of school textbooks so that our kids won’t be troubled by information about Islam. I think that’s something to look at.

Something we haven’t talked about is Catholics. Are we so used to Catholics not knowing anything about Catholicism that it’s not even to be remarked here? (Laughter.) As I traveled around and talked about religious literacy a few years ago, people were pretty aware and worried – the Catholics I spoke with – about just how bad the situation was. I remember there was a sociological study done a few years ago – some of you might know it – I think it was called “Young Adult Catholics.” And there was a finding in there that basically there was no correlation between knowledge about the Catholic tradition and how many years you took CCD classes – zero correlation.

In other words, you were just as likely to know nothing about your religion from having taken all these classes as you were having never taken them at all. I think there’s a finding here that the Catholic tradition is in really big trouble, in terms of – I mean, we already know that 10%of Americans are ex-Catholics, but it seems that Catholics are doing much worse – significantly worse – than other religious groups in terms of teaching the basics of their tradition. I guess I shouldn’t be asking you all why or anything like that, because you’re not allowed to say. (Laughter.)

COOPERMAN: I asked a priest about this and the priest said, well, we don’t even get the Bible until third theologate, meaning that in the training for the priesthood, that their training in the Bible doesn’t begin until the third year. So there is something in the Catholic tradition that is more based around the magisterium – the teachings, the accreted deposit of faith over the centuries – that’s different from the Protestant weight placed on the Bible.

And so at least on the Bible questions, it’s not surprising to me that Catholics would do less well than Protestants. And you alluded, Steve, to a couple of Gallup poll questions. As I said, there’s really very little historical data, but Glock and Stark did do a survey of Northern California churchgoers in 1963.

That study is really best-known for its findings on anti-Semitism. But among the other findings in that survey were that, among Northern California churchgoers, Protestants did considerably better on knowledge questions about the Bible than Catholics did. So in the literature of sociology on this, we have known that Protestants do better on the Bible than Catholics do.

PROTHERO: And yet, Catholic students are also taking – in Catholic parochial schools, –they do have, as part of the curriculum, I think almost everywhere, a world religions course. And that’s not working for world religions knowledge, either.

SMITH: That’s a good point. One of the things that the data show are that across the domains of knowledge, Catholics perhaps don’t perform very well, but they’re certainly very consistent. No matter what kind of question you look at, they always come in just ever so slightly below the national average. So it’s not that there’s one area in which they really fall down, and there’s also no area in which they really excel. Whether we’re talking about questions about the Bible or world religions or religion in the public schools or atheism and agnosticism, Catholics are very consistently just below the national average.

SUAREZ: If you look at the coverage of religion – and we’ll talk more about this later – I think the awareness among non-Catholics and Catholics would be very low, that the church is in that kind of crisis, that the number of ex-Catholics is far greater than that of any other religious group in America, except for self-identifying Roman Catholics.

Without the new Latino immigration, the Catholic Church’s numbers would be dropping like a rock, though maybe, given the coverage of the church lately in the popular media, having an argument about what they know and what they don’t know would be better than what’s in those stories in recent months.

We have two microphones, –and if you have questions for our panelists, please tell us who you are, where you’re from and let it fly.

SUAREZ: Krista and Stephen, any particular answer or result that made you say, wow, or gee, or just think that it was either going to be much higher or much lower – that sort of stuck out for you?

TIPPETT: Not really. I would like to just say something to the “so what” question. Part of our reaction to it is, so I don’t know if it matters if people know who Jonathan Edwards is. I kind of wish they knew a little bit about Niebuhr and Heschel – but not who they were, but what their thinking was –

SUAREZ: Who? That’s a homework assignment for the rest of you.

TIPPETT: So I agree with you that to be a citizen of the 21st century, we need to be more literate. Americans need to know more. I also think our public lives, our common lives, can use all the assets we can bring to it, including theological perspective, including these practices of care for the other that religious traditions have cultivated across centuries.

And ultimately, that’s not just about knowledge, but knowledge is a part of that. As I said, maybe people start with service and go back to knowledge, but to me, there is a big “so what” here, even though I would quibble with some of the questions – whether it’s those particular things.––

Q: My name is Chris Stephenson from America’s Quilt of Faith in Northern Virginia. Let’s say that we make some progress in religious literacy. And here’s a question I’d like to ask. It is hypothetical. Are there differences between an America that does better in 10 years, say, on a similar religious survey because they were taught religion in public schools and universities and one that does better because they, collectively – we Americans had been more active in our different faiths? If so, what are these differences? And if not, why not?

PROTHERO: I’m sure Pew is not allowed to answer hypothetical questions, is that right? So can I do that one? I think that there’s a difference between learning about your own religion inside your own religious tradition, including learning about others from the perspective of your tradition, and learning about things in the public schools or in the media or in a public forum that is not religiously committed.

A lot of people have said to me, OK, it’s a religious problem; it should be solved by religious people. Don’t involve the public schools. Don’t involve the media. Let Catholics deal with it. But the reality is, churches and synagogues and mosques and Zen centers, they’re not set up to educate you about other religions. That’s not their job.

The job of the public schools is to educate our young people about the world and to prepare them to be citizens. And I think the question is, do you accept the premise that I have argued – and others, as well – that knowing about the world includes knowing about the religious traditions of the world, and that that’s something we need to do to equip for citizenship.

So I think there would be a difference in those two hypotheticals, and I think the one where we learn about religions inside our public institutions would, in some ways, be preferable because we would be getting a kind of collective, civic conversation about religions going, rather than an intra – inside a particular religious tradition.

That said, I totally welcome conversations about other religions inside particular religious perspectives. I think some of those are incendiary. I’m not sure I would want to send my kid to a class on Islam that was taught by the Rev. Franklin Graham. But some of them are informative.

SUAREZ: Krista, what do you think? Is a country that does better on this test, both inside and outside the faith, a better country down the road?

TIPPETT: One would hope so. I think that’s all I can say.

SUAREZ: Fair answer.

Q: I have two questions. Did anybody harvest data on standardized testing and whether there were religious literacy questions asked?

SMITH: Well, no. – When we looked at the questions that had been asked in the past, we tried to focus our results on things that we might be able to tap into, in terms of trend data. So we’d be most interested in questions that had been asked on nationally representative surveys of adults because our own samples don’t tend to deal with student populations or with minors.

That said, I think it would be very interesting to look and see if there have been questions about religious history, for instance, on standardized tests or college admissions exams. I think that would be something very interesting. And that might be a way to, at least for a certain segment of the population, to try and look back over time and see what kind of a trajectory these things had.

PROTHERO: I think you could keep that question in mind for the panel today that includes some religious educators and educators in public schools.

SUAREZ: In my business, that’s called forward-promoting. Very good.

Q: George Conklin from Berkeley. Several decades ago, Bob Bellah and his colleagues at UC-Berkeley did a study of faith in America, published as “Habits of the Heart.” They identified a pattern of aggregated faith with a thread of Buddhism, a thread of Catholicism, and they termed that “Sheila-ism.” Is Sheila-ism on the increase today?

COOPERMAN: Yes, and we don’t have that data from this survey, but we did a survey last year on the mixing and matching of religious faiths in the United States. Again, historical data is a problem, but we had some, and the indications in the questions that we do have trend data on are that it’s on the rise.

Where our particular contribution on this was, being able to correlate how often people go to religious services with their syncretic beliefs, if you will – not that we ever use that word in the report. But what we found, for example, is that even among Roman Catholics who tell us that they go to church every single week – once a week or more – about a quarter of them believe in reincarnation and about 20% believe in astrology.

And if I remember off the top of my head, about 20% – or maybe about 15% – believe in spiritual energy in physical objects, such as crystals and mountains. We had a wonderful set of questions about this that demonstrated all across the board, including among evangelical Protestants who go to church once a week – if you go to an evangelical Protestant church and you sit in your pew this Sunday and you look down at the 10 people in your pew, one of the 10 of you believes in reincarnation, – if your church is nationally representative.

SMITH: Can I just point out one other thing to follow up on that? In a similar vein, we’ve also done other surveys over the last few years, and one of the most interesting questions we’ve asked is about what people think it takes to attain eternal life, and who people think can attain eternal life.

Is this something that only members of your faith can achieve, or is it something that members of other faiths can achieve? And our surveys have shown that lots of people – majorities of people – think that many faiths, not just their own, can lead to eternal life. We found this so interesting that we actually went back and did follow-up surveys on this question and asked people, specifically, when they say many faiths can lead to eternal life, what do they mean?

Are they talking just about members of the Christian denomination next door? Are these Methodists who are sort of grudgingly admitting that Lutherans can get to heaven, or are these Christians who mean that, you know what, Judaism and Islam and Hinduism and even non-belief are things that can get you to eternal life? And it turns out people really mean other faiths. Christians, when they say many religions can lead to eternal life, mean religions other than Christianity.

I think that points in a similar direction. I also think it raises an interesting question, though, with respect to religious knowledge. I mean, that’s a pretty open-minded thing to say, right – that many religions can lead to eternal life. One question I have – I don’t think these data answer it directly – is, do these people realize that, that may not be what their religion teaches?

And if they did realize that, would it change their belief, would it change their perspective? I mean, we know, on the one hand, that generally speaking, knowledge of people from other faiths is associated with more tolerance, more favorable views. But this is one area where that might not be the case. If you actually were to come to learn that your religion didn’t teach that many religions can lead to eternal life, would that lead to you holding a less-inclusive view about these things? I don’t know.

SUAREZ: That set of data, over time, is given tremendous significance by Bob Putnam in his new book, American Grace, where he looks at people who are adherents of faiths that make very concrete, exclusive faith claims, and then asks the members of those faiths whether people who believe other things can still get to heaven based on being a decent person.

Very, very high percentages – and the trend is up over time, which may be an argument for knowing people. It’s hard to condemn the Jew next door if you know the Jew next door. We are out of time for this session. (Applause.)

This written transcript has been edited by Amy Stern for clarity and grammar.

Photo credit: Eric Swanson/Corbis