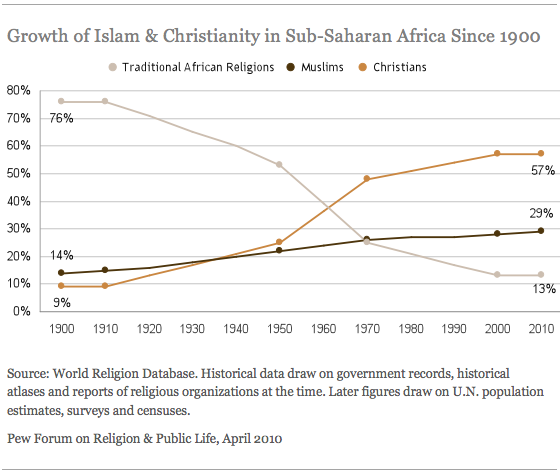

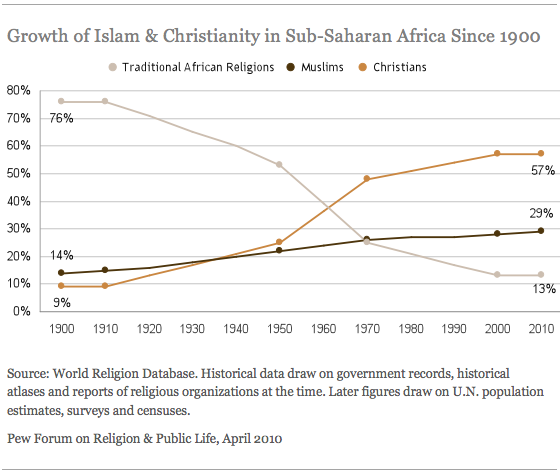

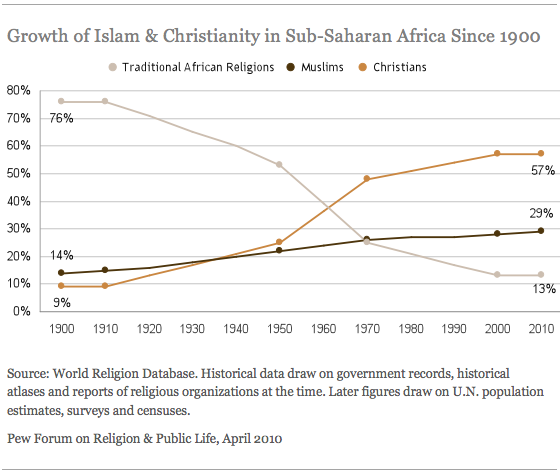

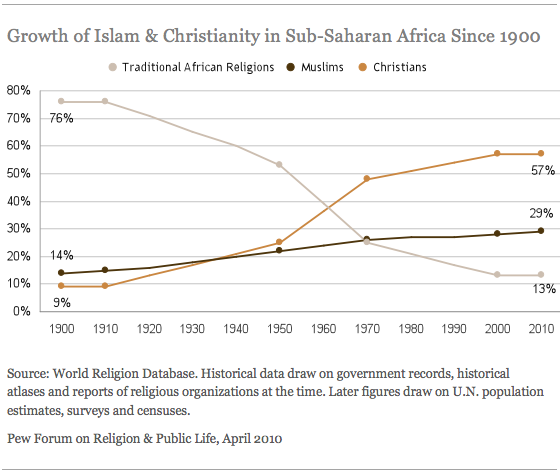

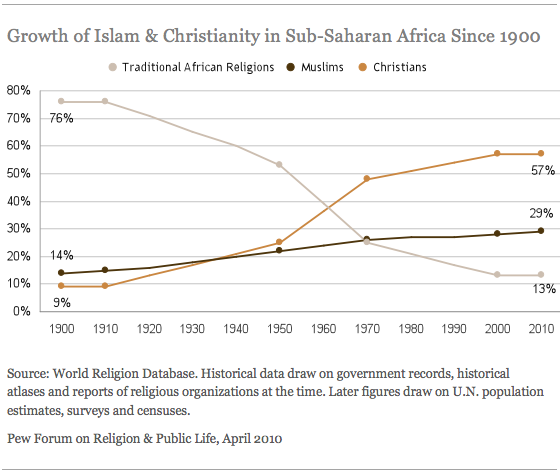

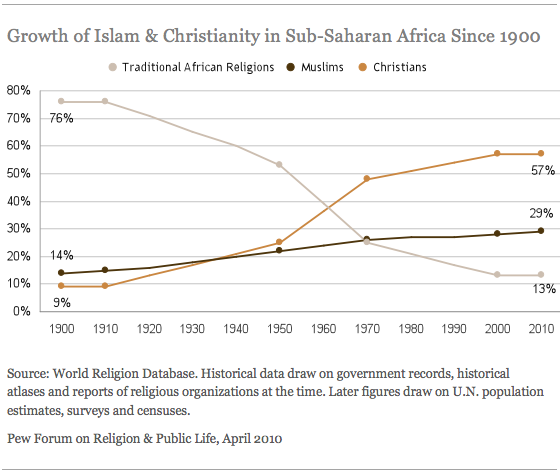

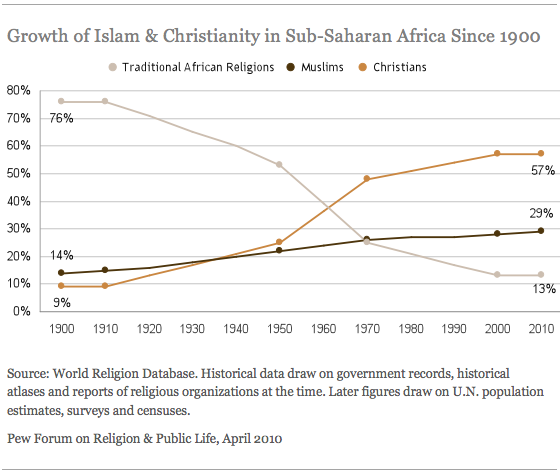

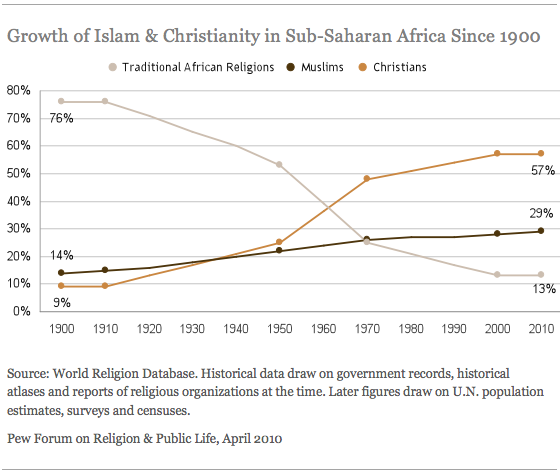

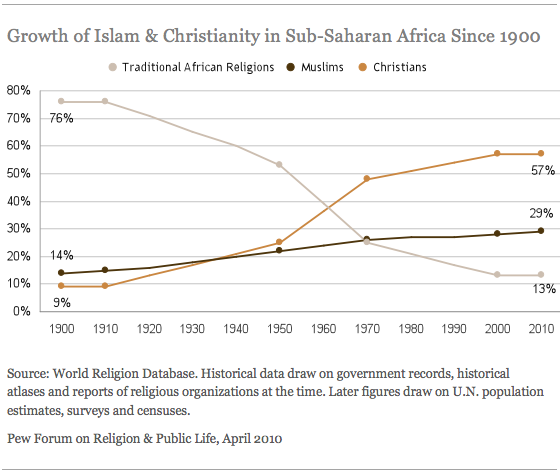

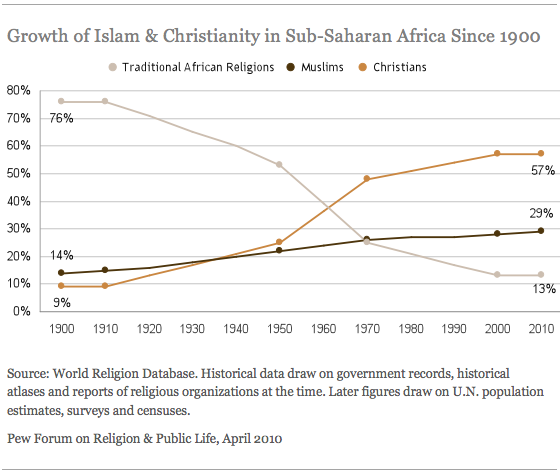

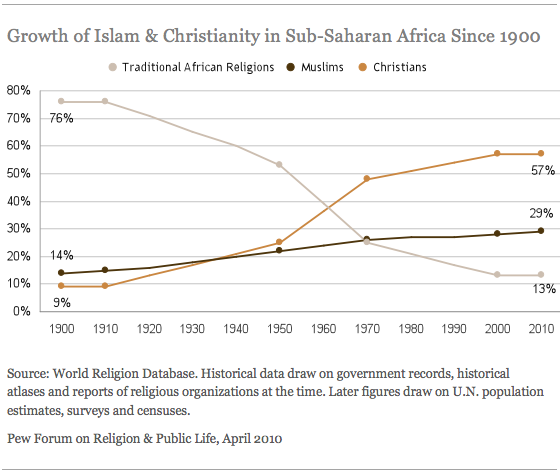

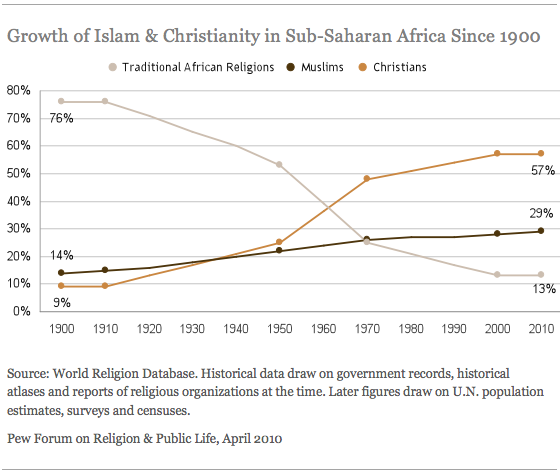

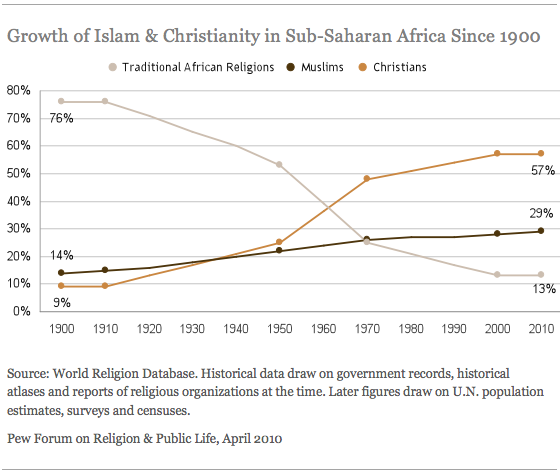

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world’s Muslims (15%).1

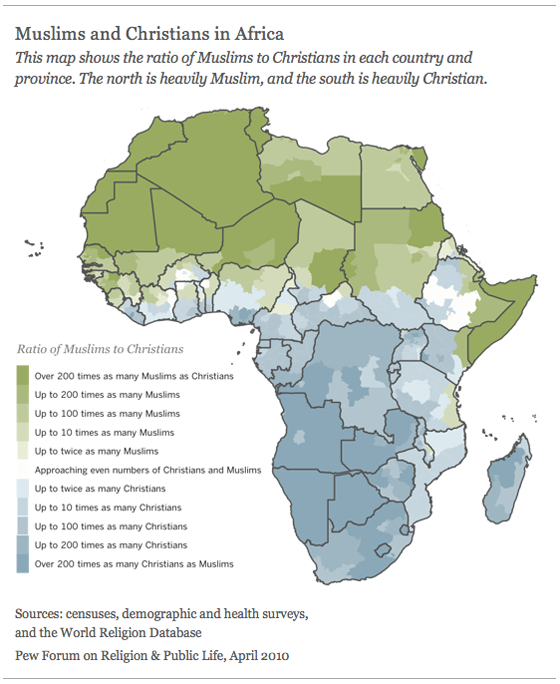

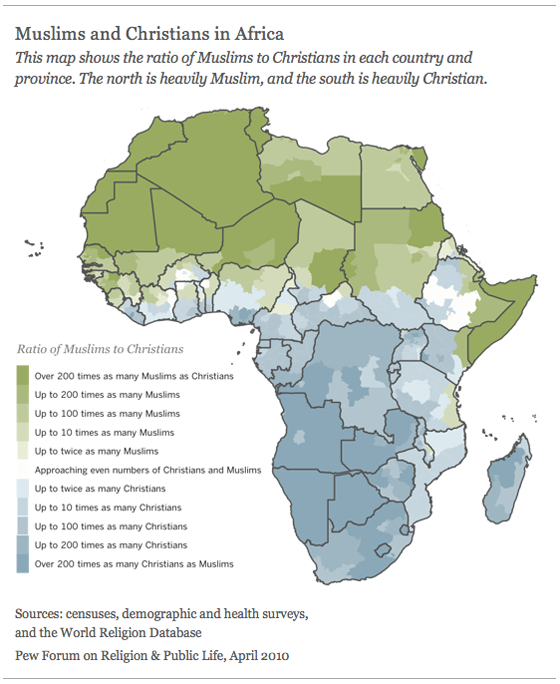

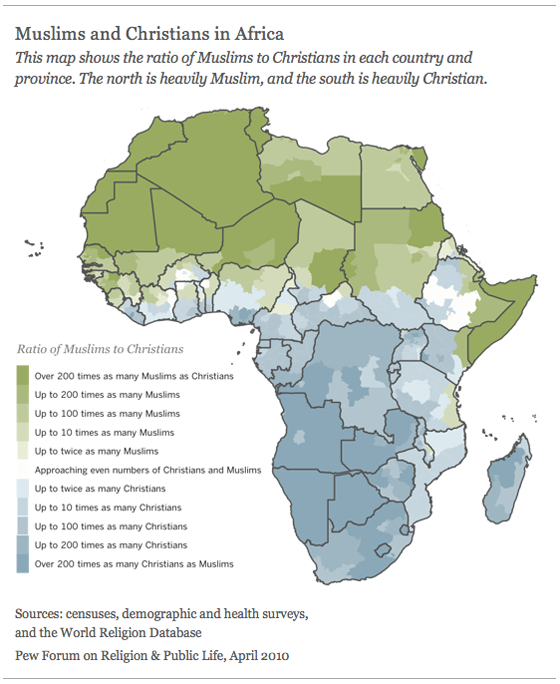

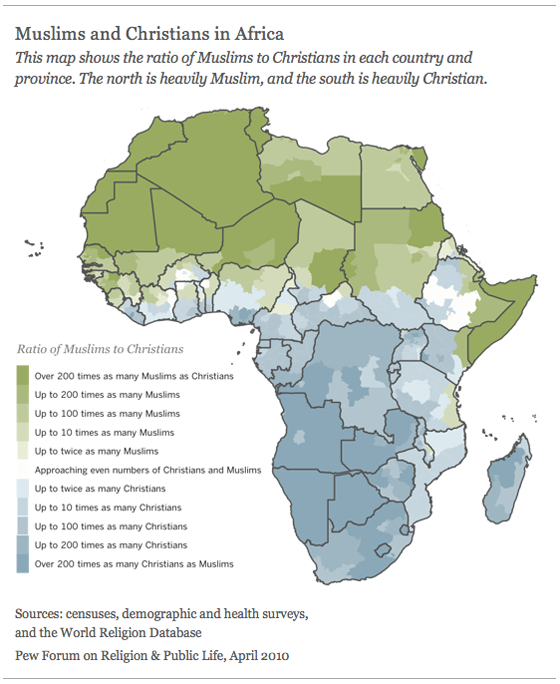

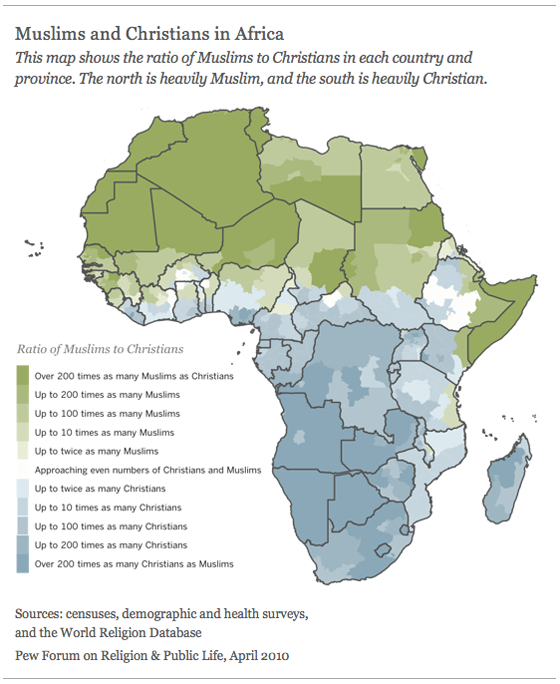

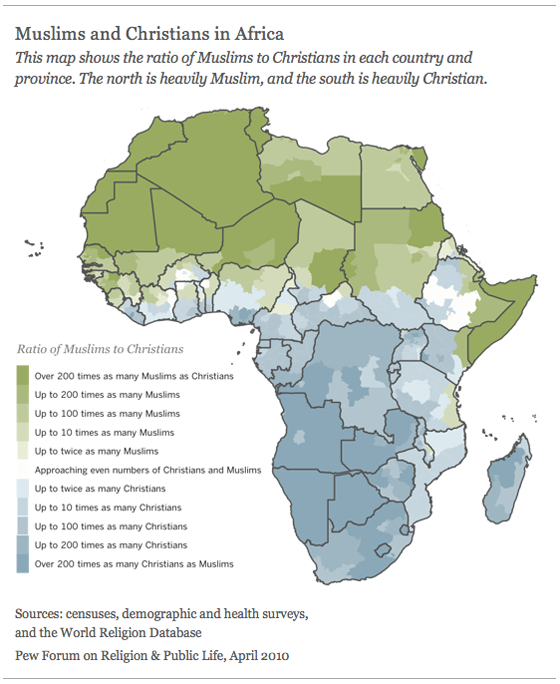

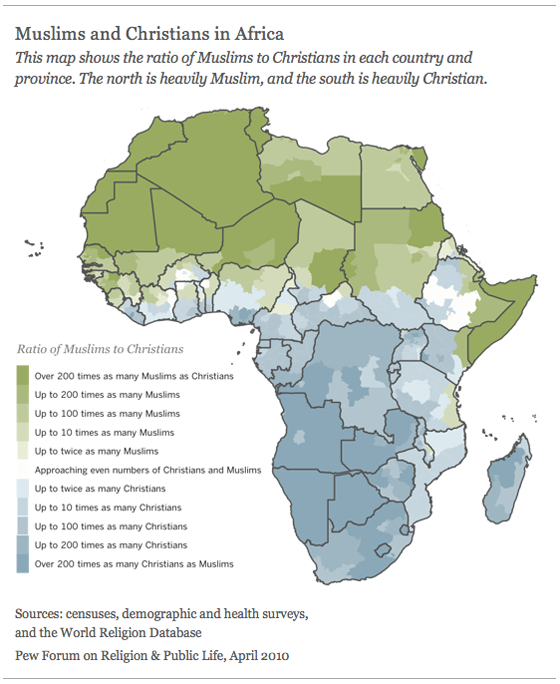

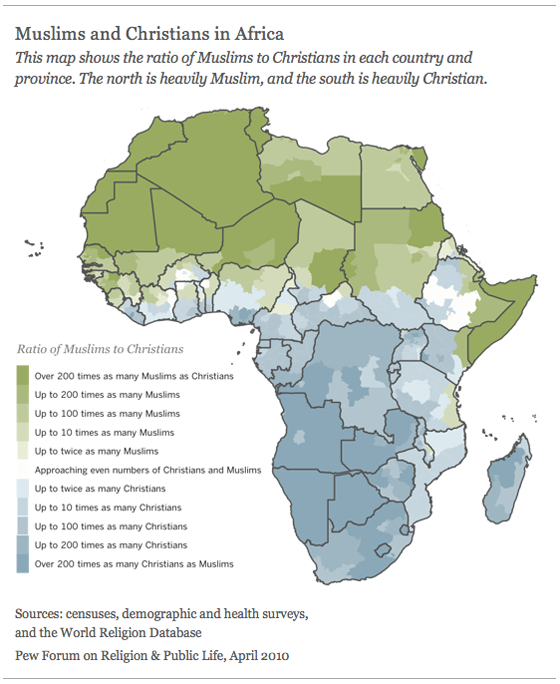

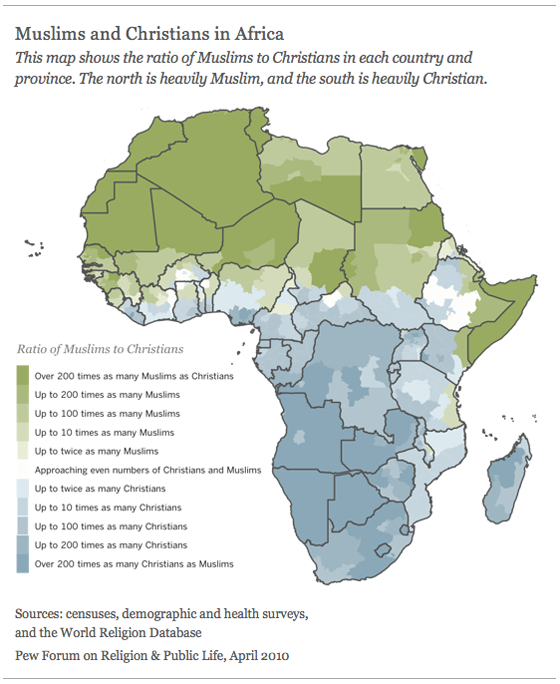

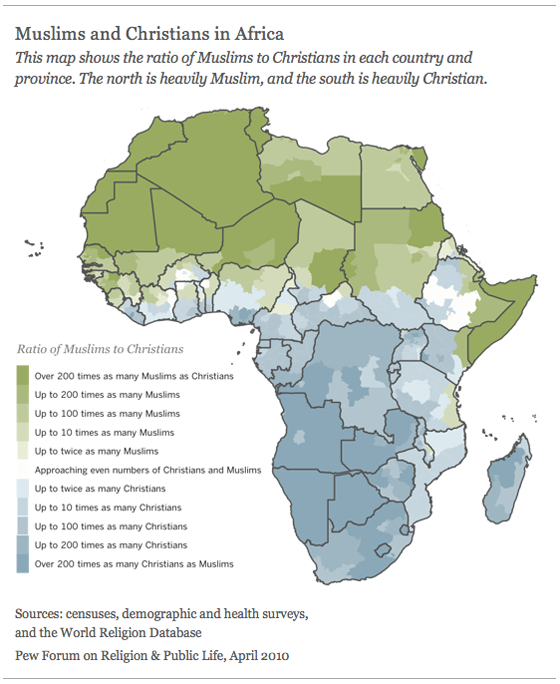

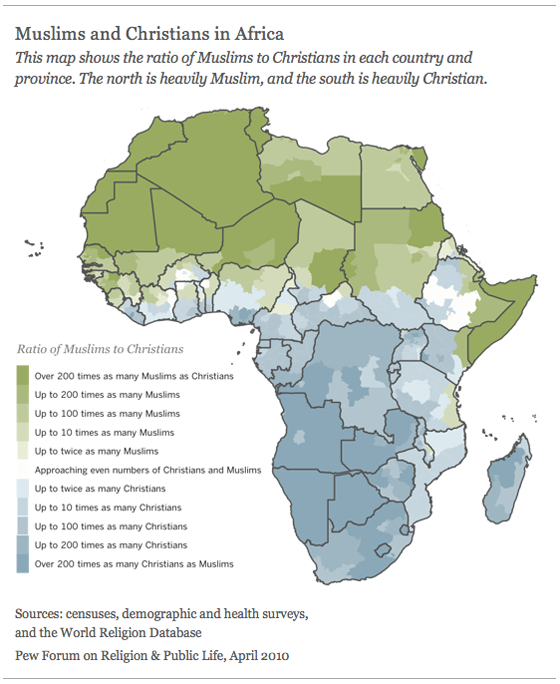

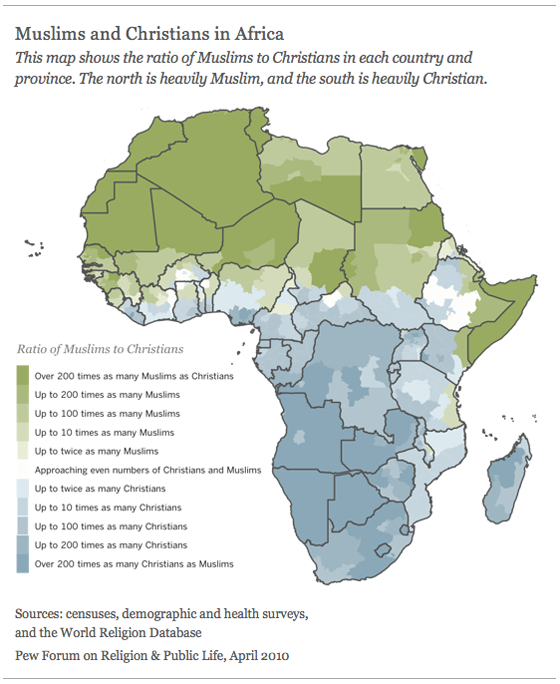

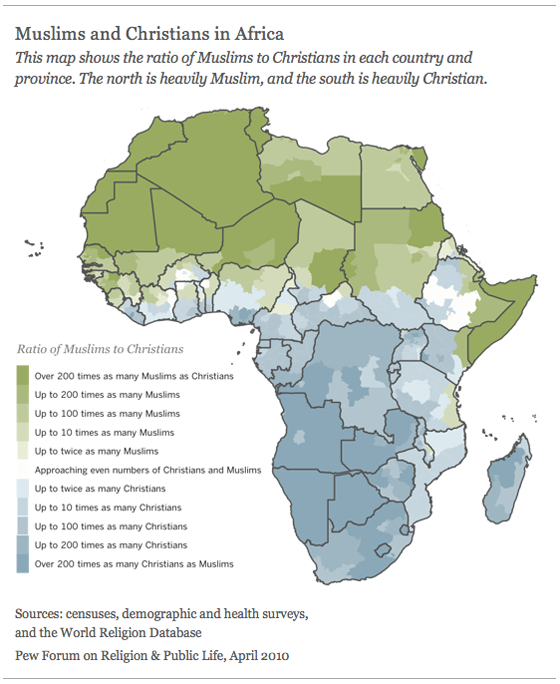

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda’s first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

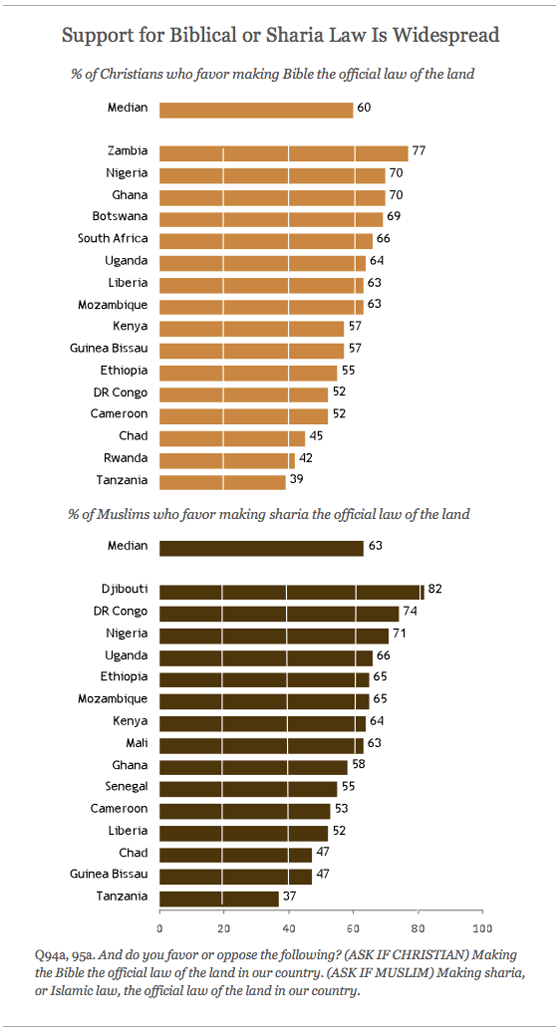

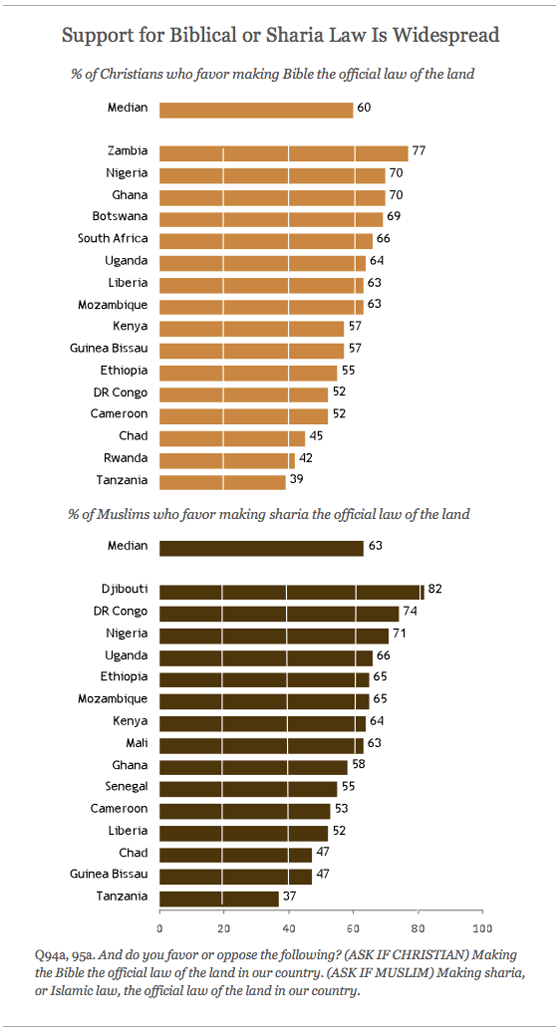

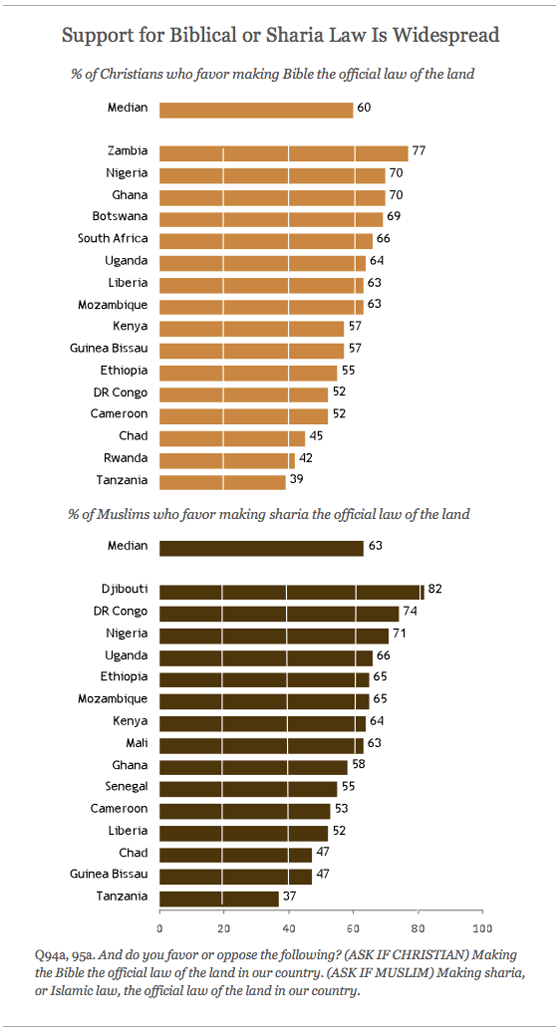

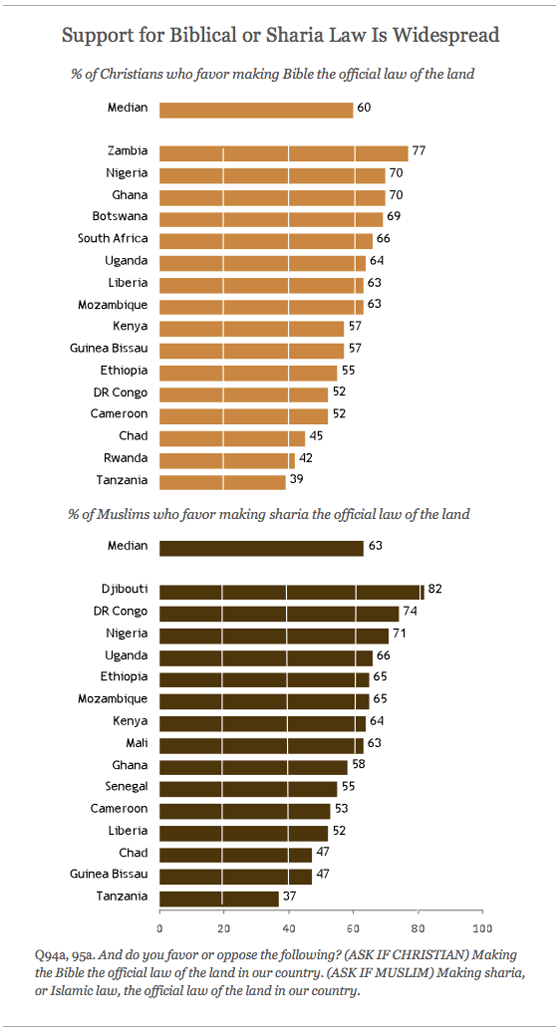

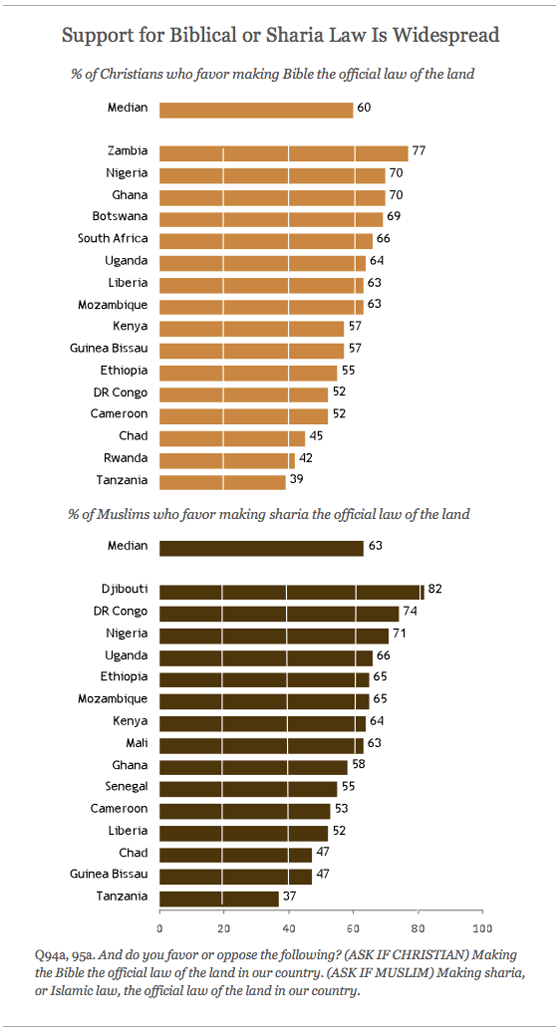

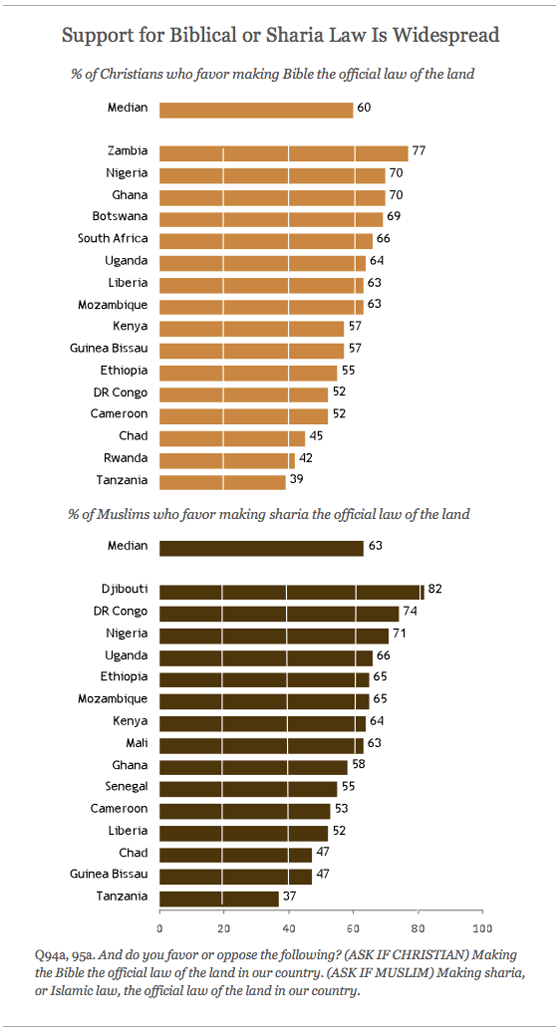

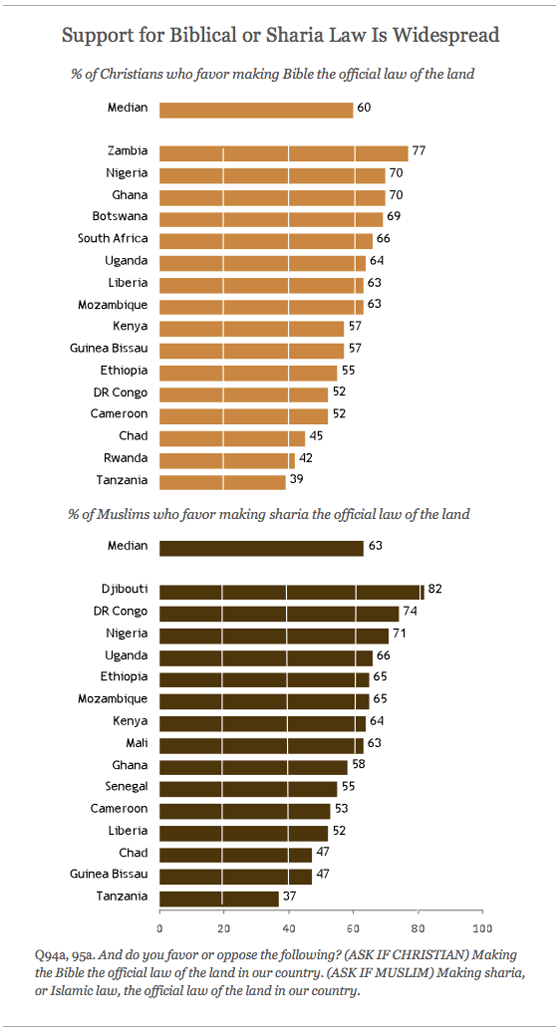

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort – the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project – that aims to increase people’s knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

Executive Summary

The vast majority of people in many sub-Saharan African nations are deeply committed to the practices and major tenets of one or the other of the world’s two largest religions, Christianity and Islam. Large majorities say they belong to one of these faiths, and, in sharp contrast with Europe and the United States, very few people are religiously unaffiliated. Despite the dominance of Christianity and Islam, traditional African religious beliefs and practices have not disappeared. Rather, they coexist with Islam and Christianity. Whether or not this entails some theological tension, it is a reality in people’s lives: Large numbers of Africans actively participate in Christianity or Islam yet also believe in witchcraft, evil spirits, sacrifices to ancestors, traditional religious healers, reincarnation and other elements of traditional African religions.2

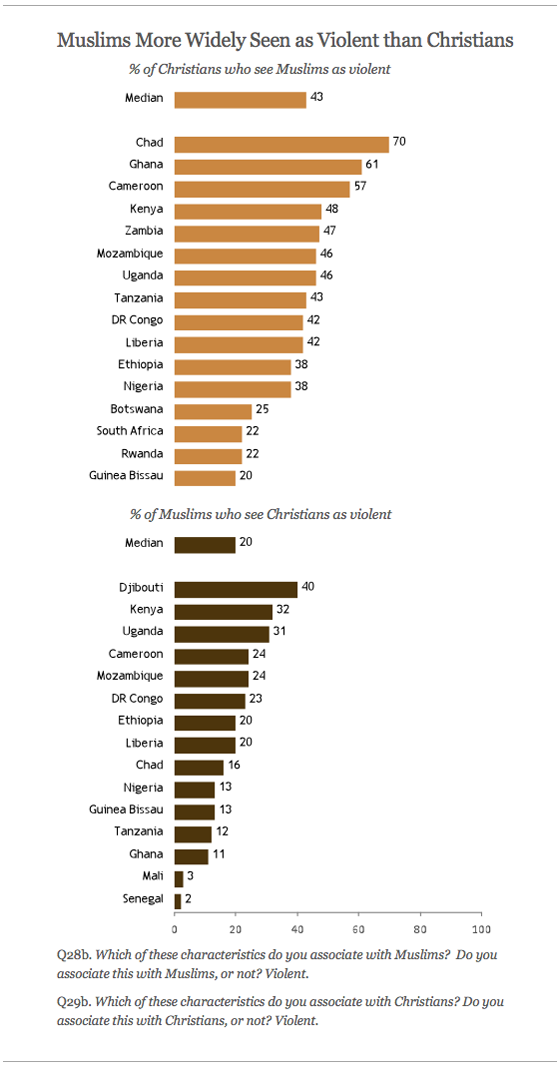

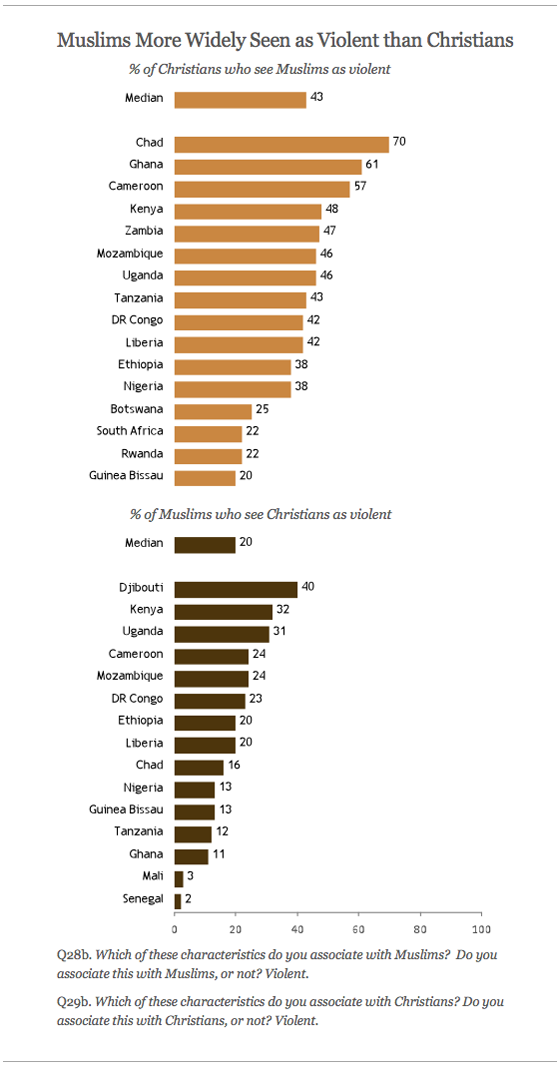

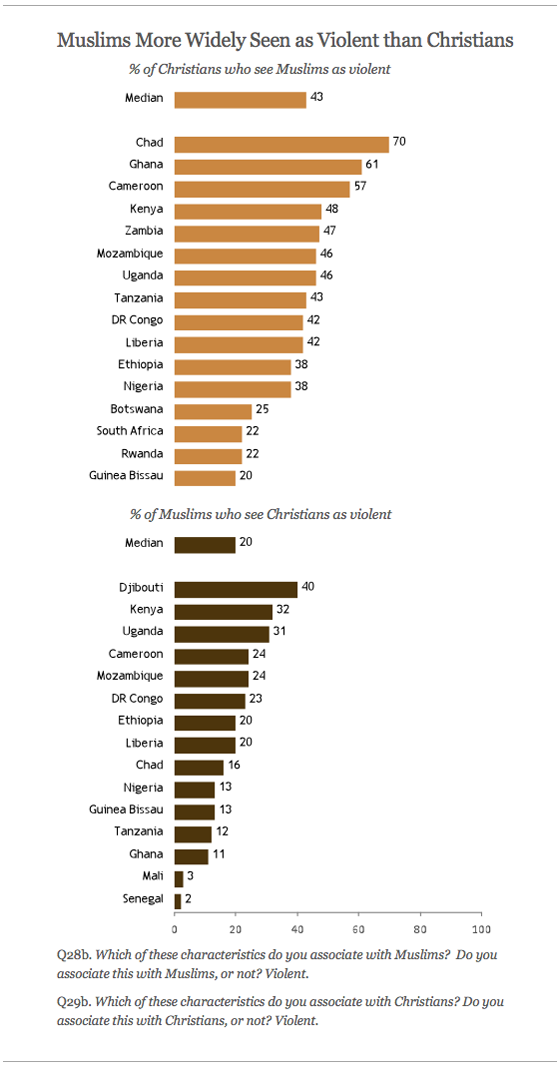

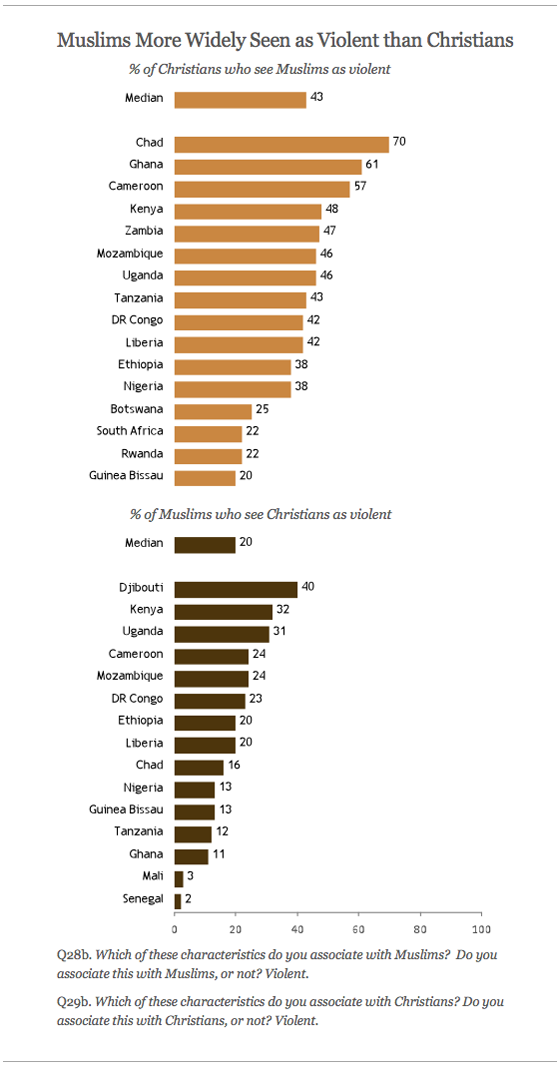

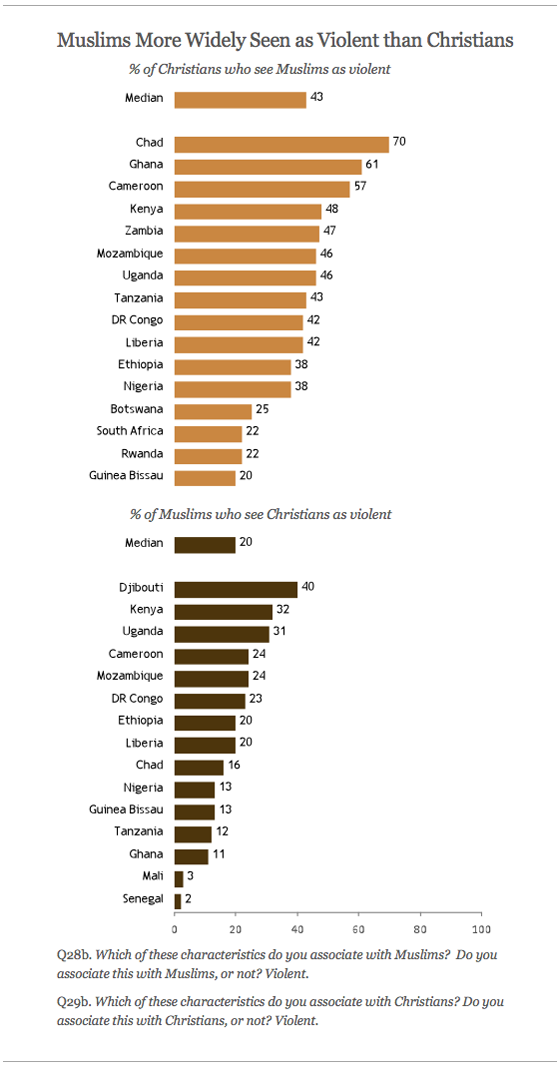

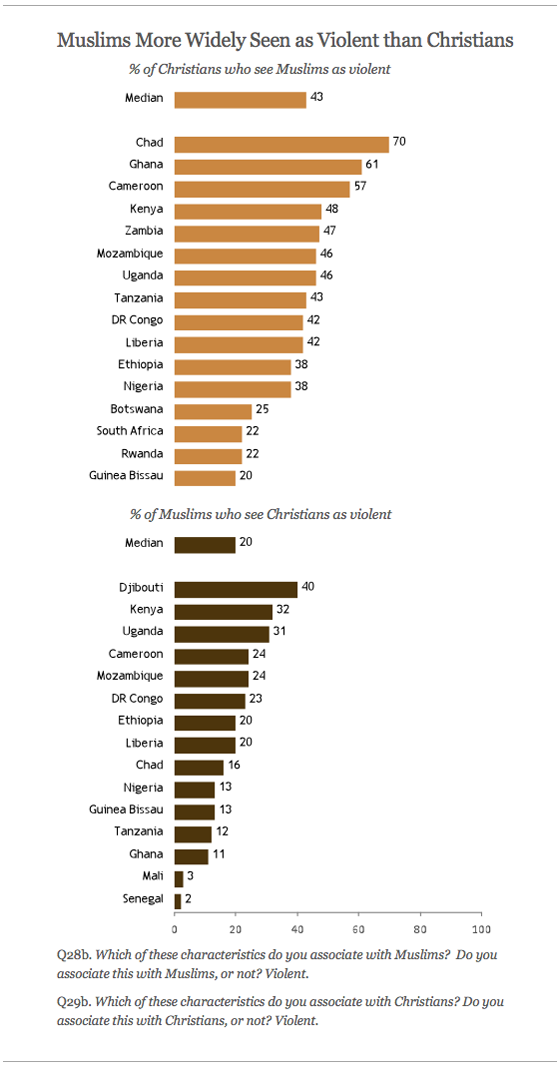

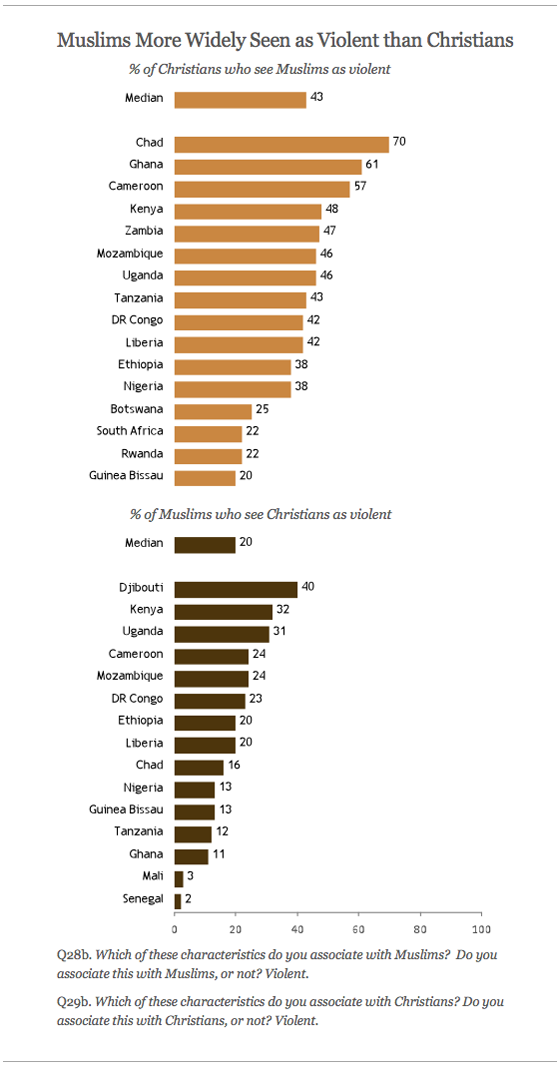

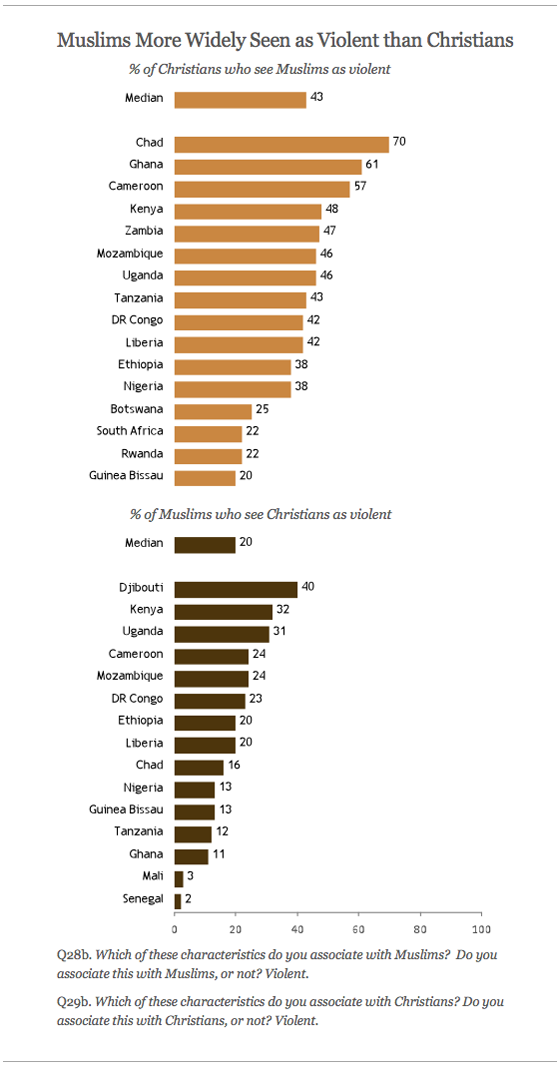

Christianity and Islam also coexist with each other. Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa describe members of the other faith as tolerant and honest. In most countries, relatively few see evidence of widespread anti-Muslim or anti-Christian hostility, and on the whole they give their governments high marks for treating both religious groups fairly. But they acknowledge that they know relatively little about each other’s faith, and substantial numbers of African Christians (roughly 40% or more in a dozen nations) say they consider Muslims to be violent. Muslims are significantly more positive in their assessment of Christians than Christians are in their assessment of Muslims.

There are few significant gaps, however, in the degree of support among Christians and Muslims for democracy. Regardless of their faith, most sub-Saharan Africans say they favor democracy and think it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, there is substantial backing among Muslims and Christians alike for government based on either the Bible or sharia law, and considerable support among Muslims for the imposition of severe punishments such as stoning people who commit adultery.

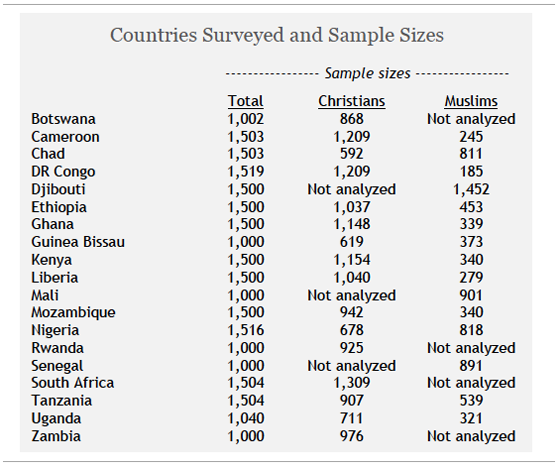

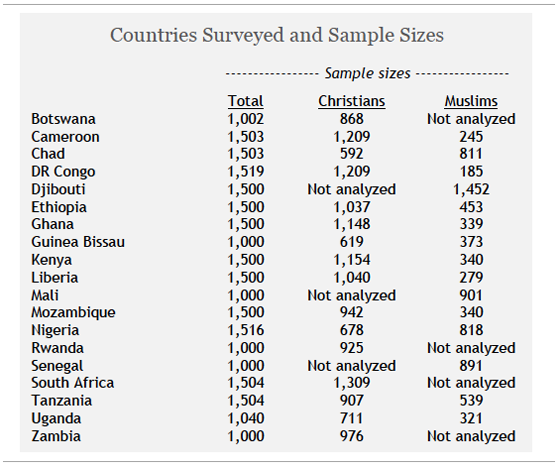

These are among the key findings from more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews conducted on behalf of the Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 sub-Saharan African nations from December 2008 to April 2009. (For additional details, see the survey methodology (PDF).) The countries were selected to span this vast geographical region and to reflect different colonial histories, linguistic backgrounds and religious compositions. In total, the countries surveyed contain three-quarters of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa.

Other Findings

In addition, the 19-nation survey finds:

-

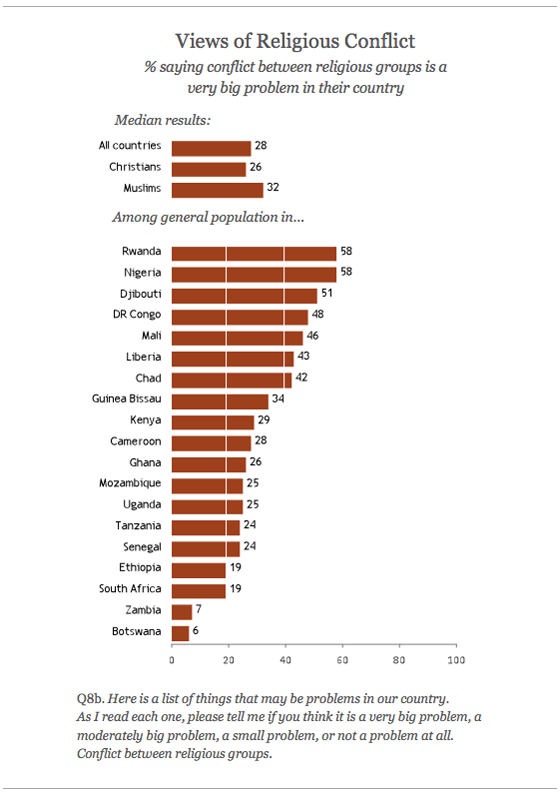

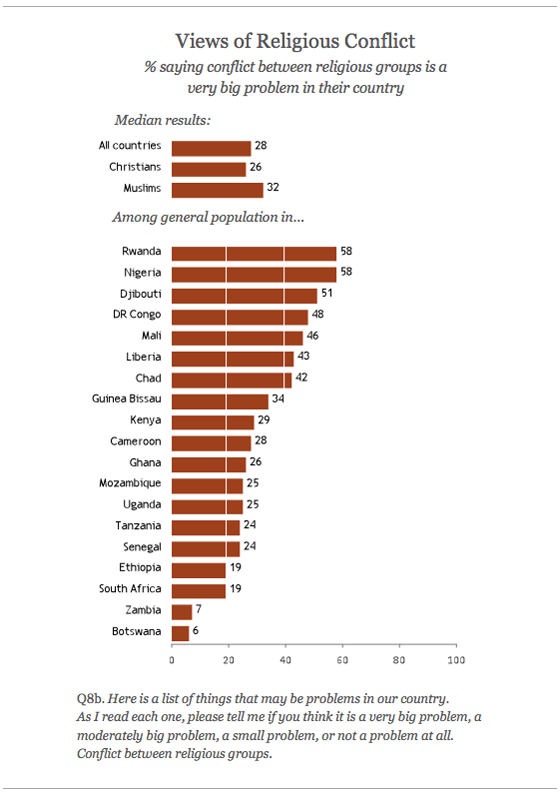

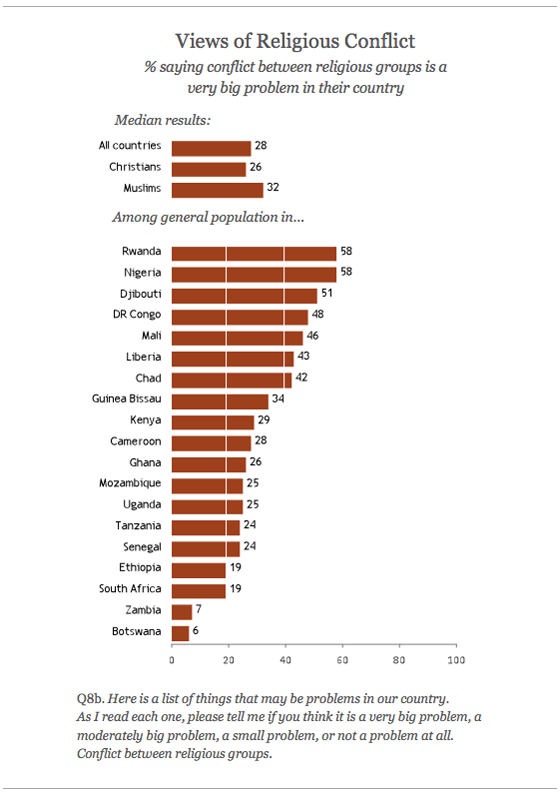

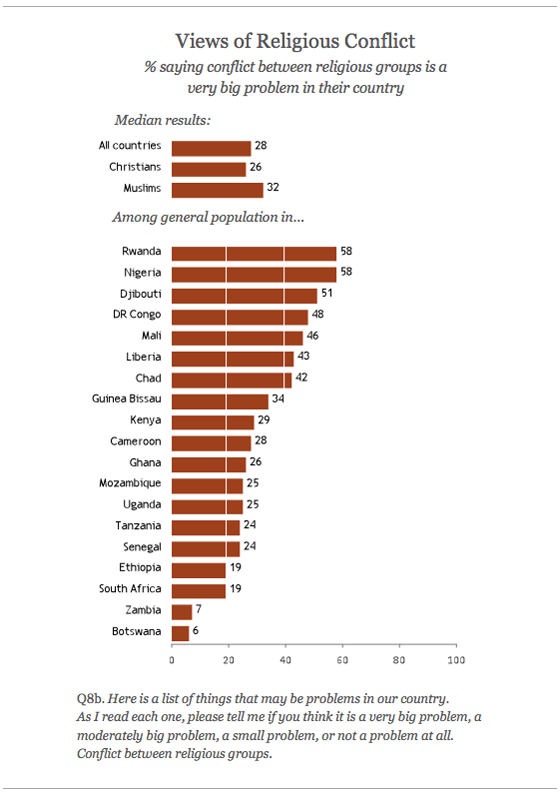

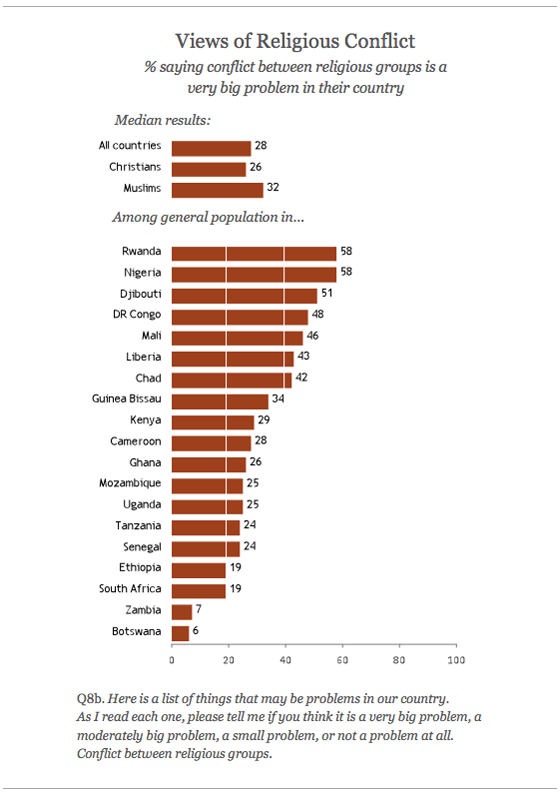

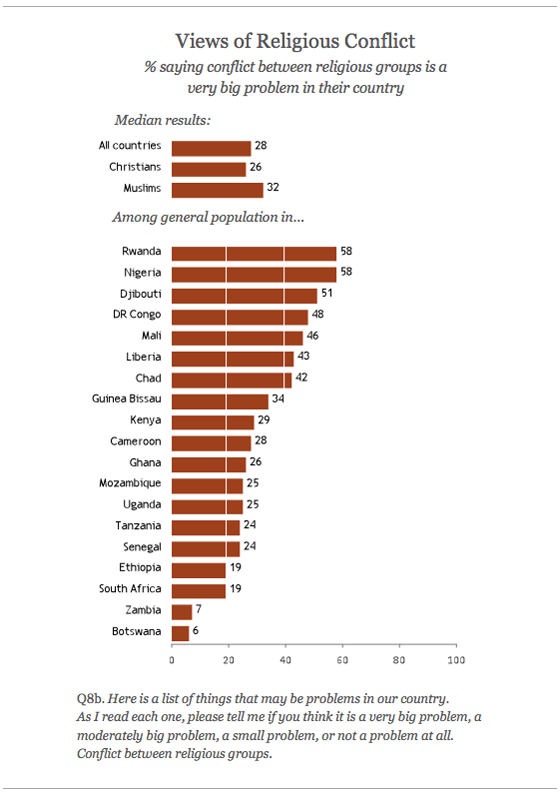

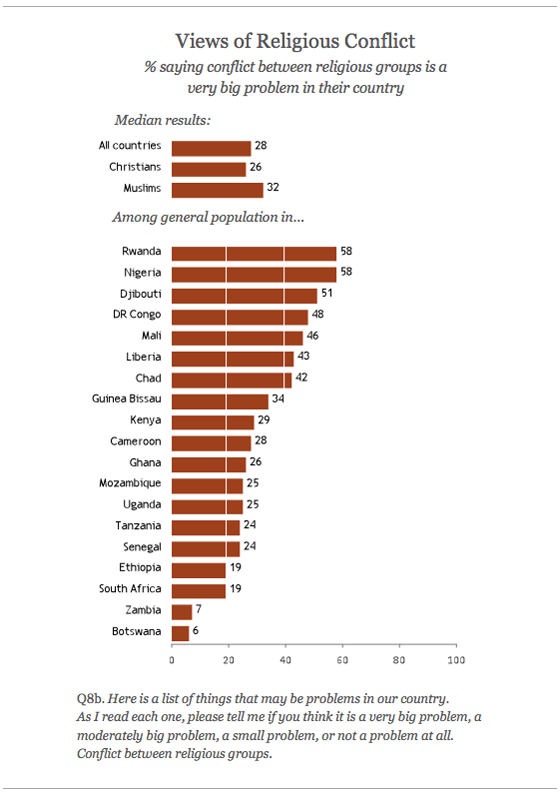

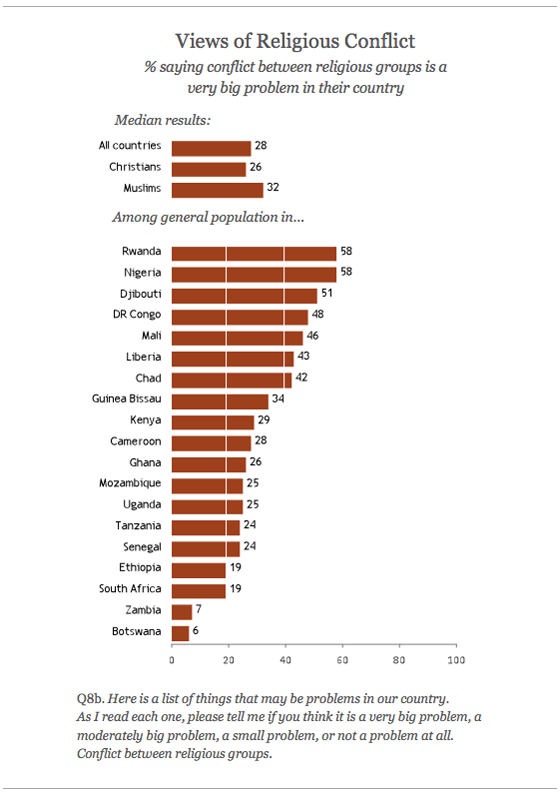

- Africans generally rank unemployment, crime and corruption as bigger problems than religious conflict. However, substantial numbers of people (including nearly six-in-ten Nigerians and Rwandans) say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country.

- The degree of concern about religious conflict varies from country to country but tracks closely with the degree of concern about ethnic conflict in many countries, suggesting that they are often related.

- Many Africans are concerned about religious extremism, including within their own faith. Indeed, many Muslims say they are more concerned about Muslim extremism than about Christian extremism, and Christians in four countries say they are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism.

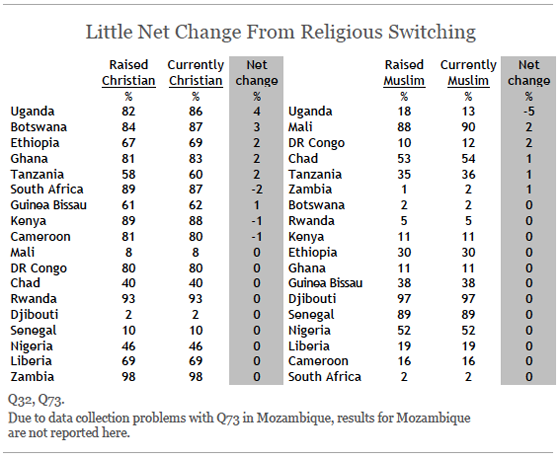

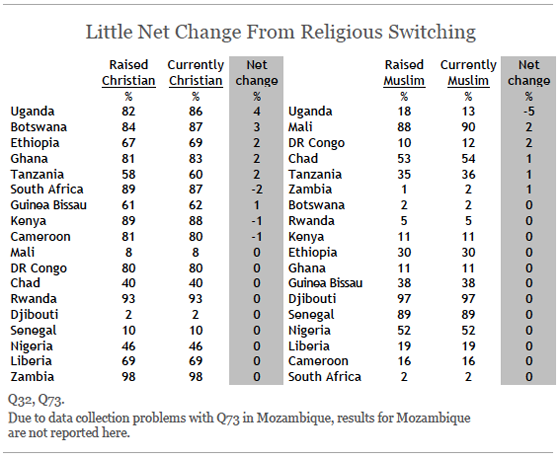

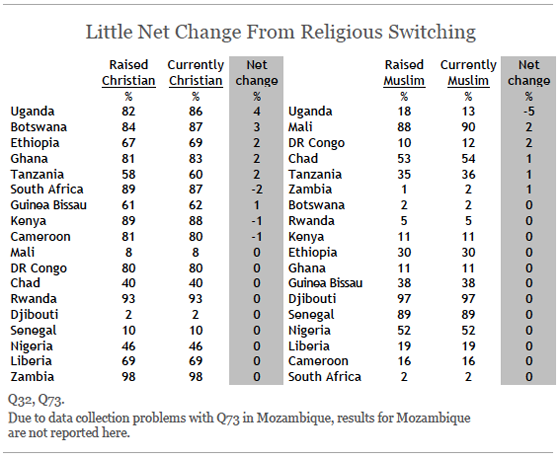

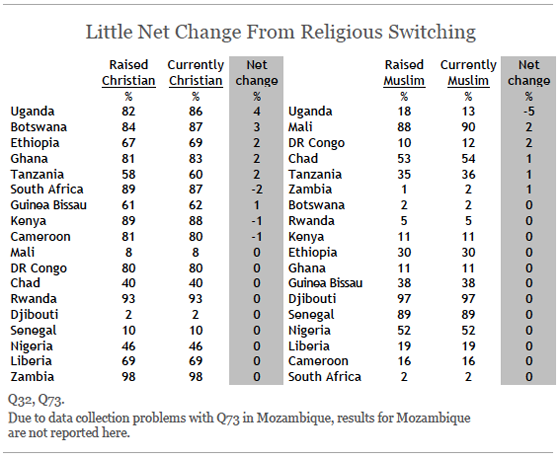

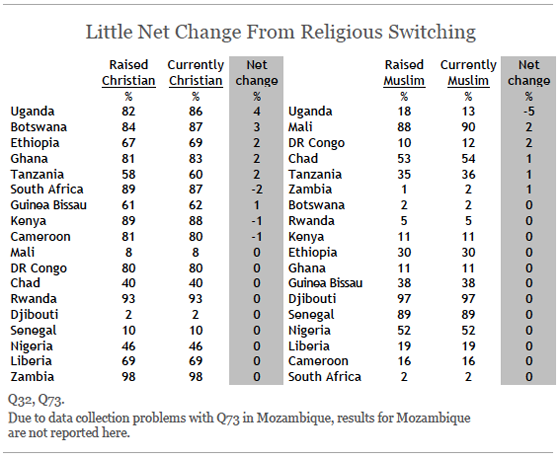

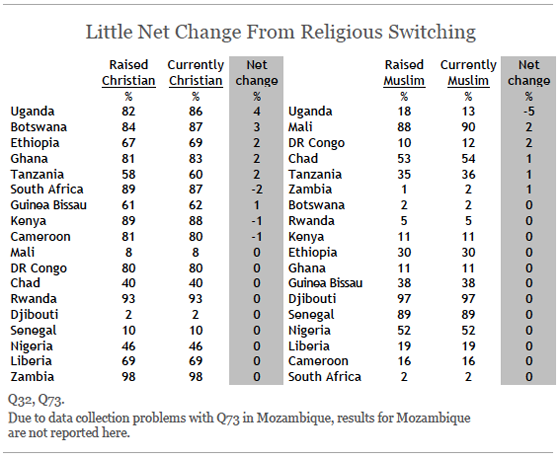

- Neither Christianity nor Islam is growing significantly in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other; there is virtually no net change in either direction through religious switching.

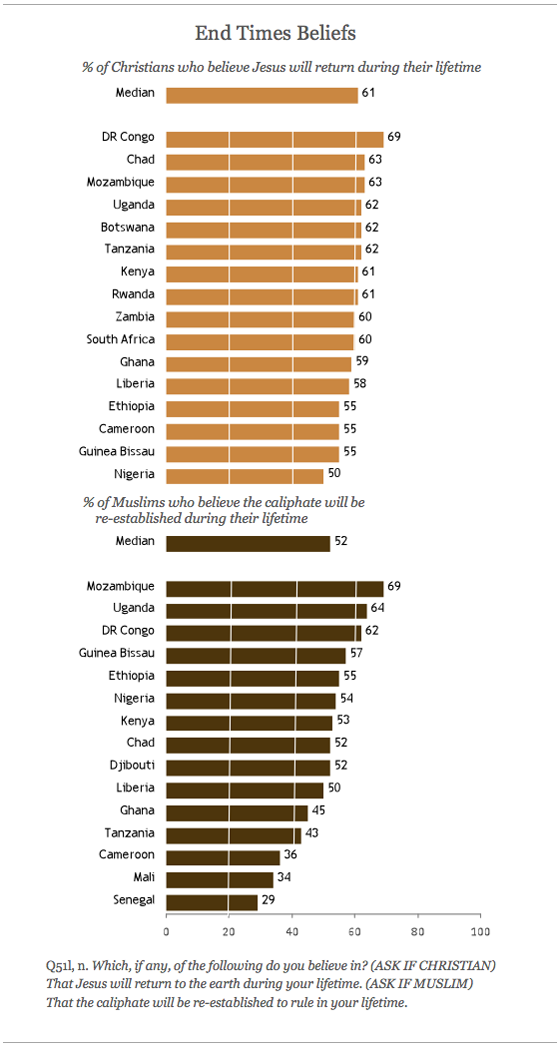

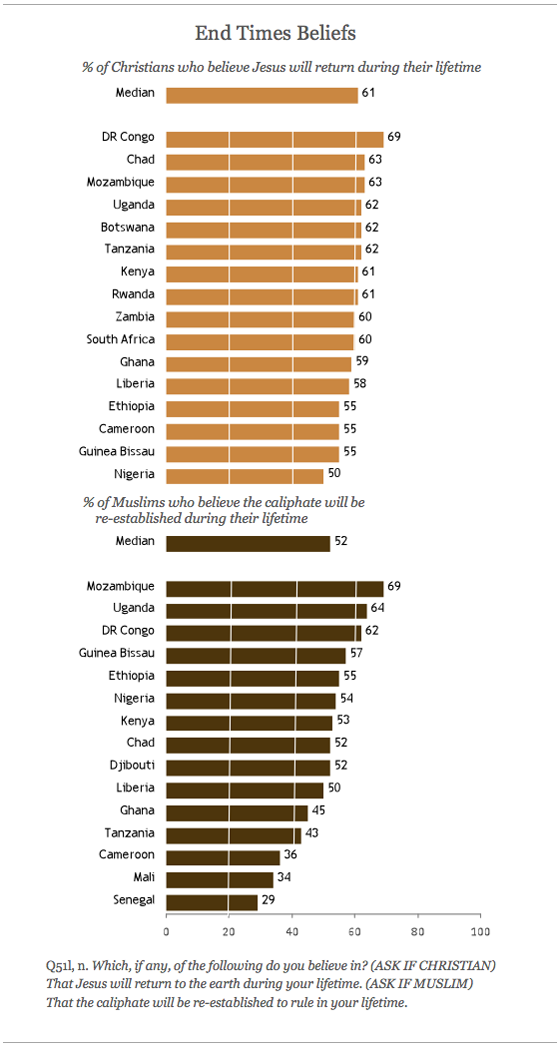

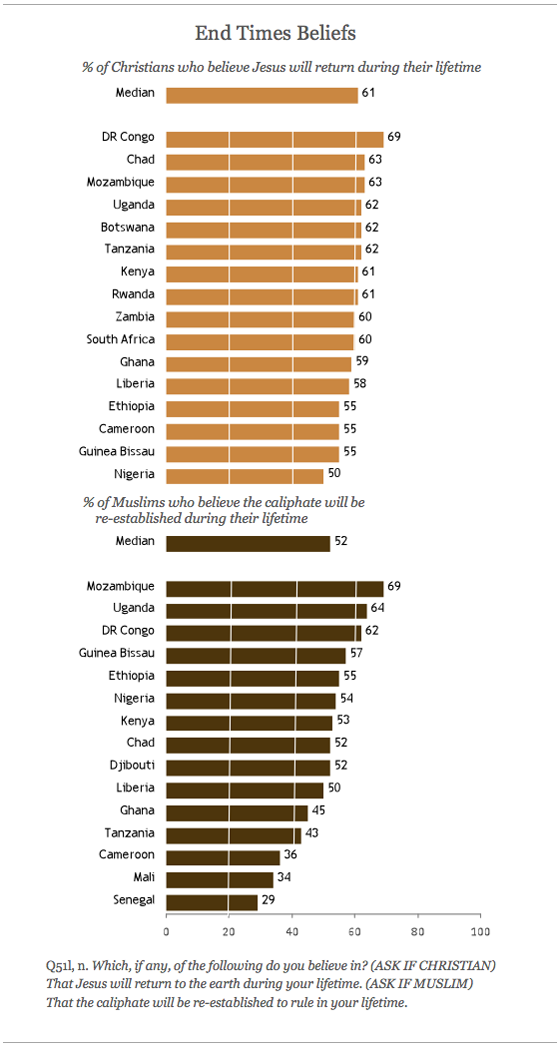

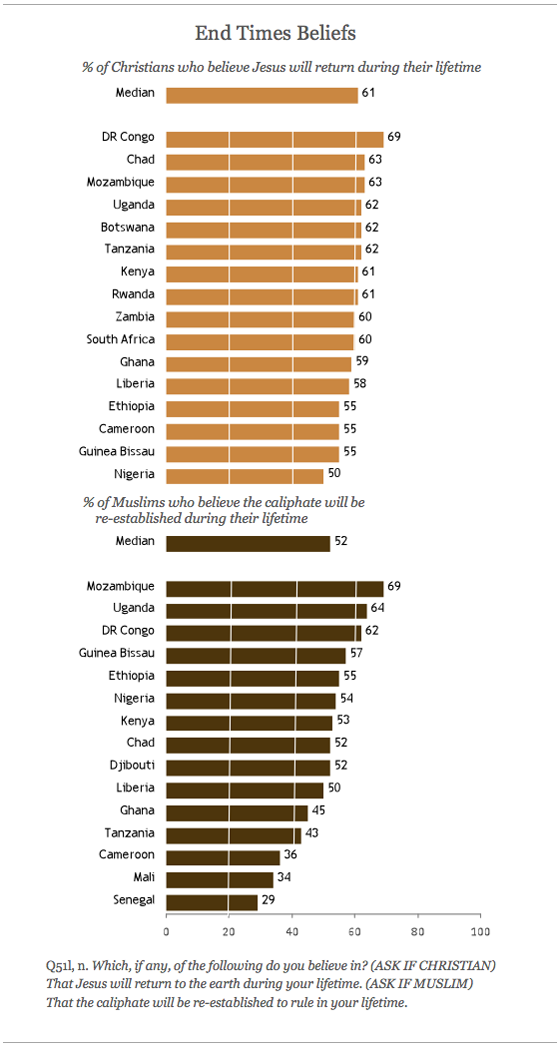

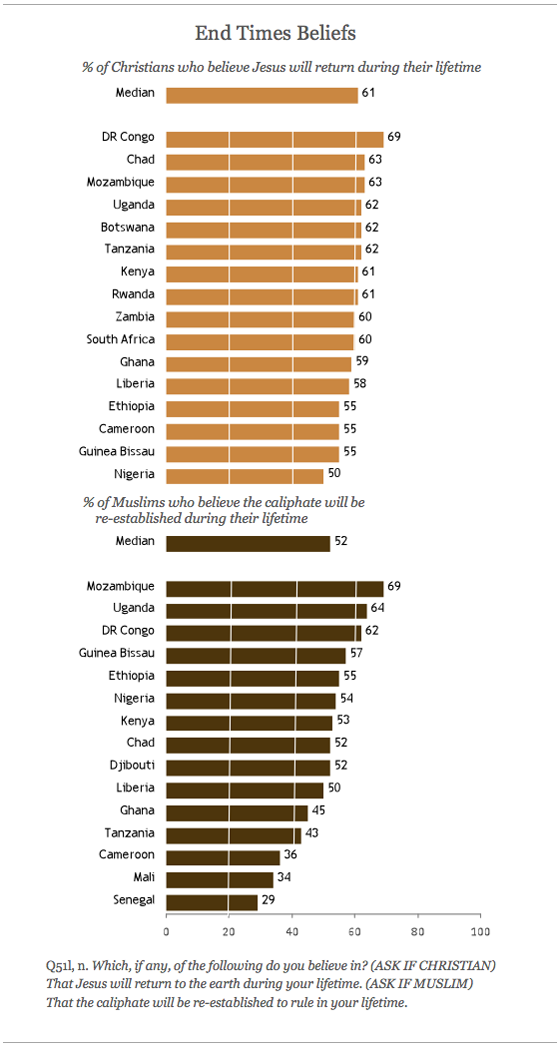

- At least half of all Christians in every country surveyed expect that Jesus will return to earth in their lifetime, while roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to live to see the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule.

- People who say violence against civilians in defense of one’s religion is rarely or never justified vastly outnumber those who say it is sometimes or often justified. But substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say violence against civilians in defense of one’s religion is sometimes or often justified.

- In most countries, at least half of Muslims say that women should not have the right to decide whether to wear a veil, saying instead that the decision should be up to society as a whole.

- Circumcision of girls (female genital cutting) is highest in the predominantly Muslim countries of Mali and Djibouti but is more common among Christians than among Muslims in Uganda.

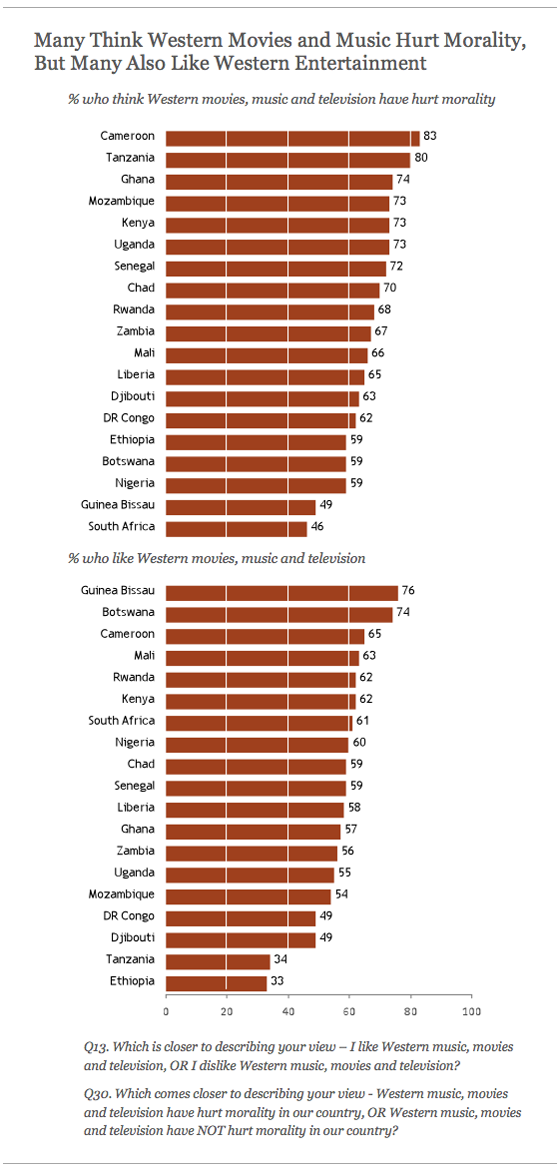

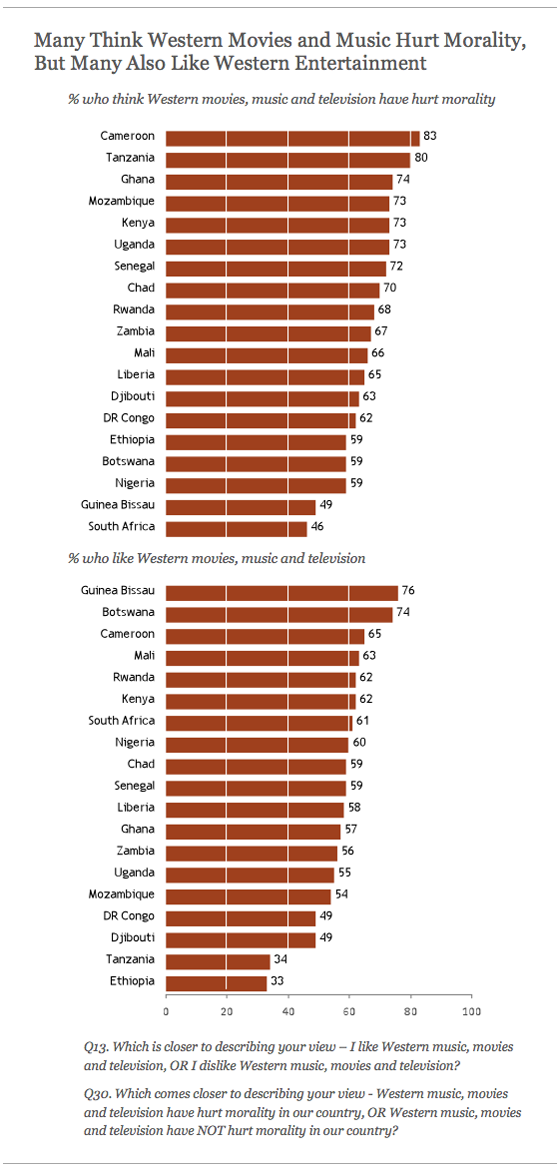

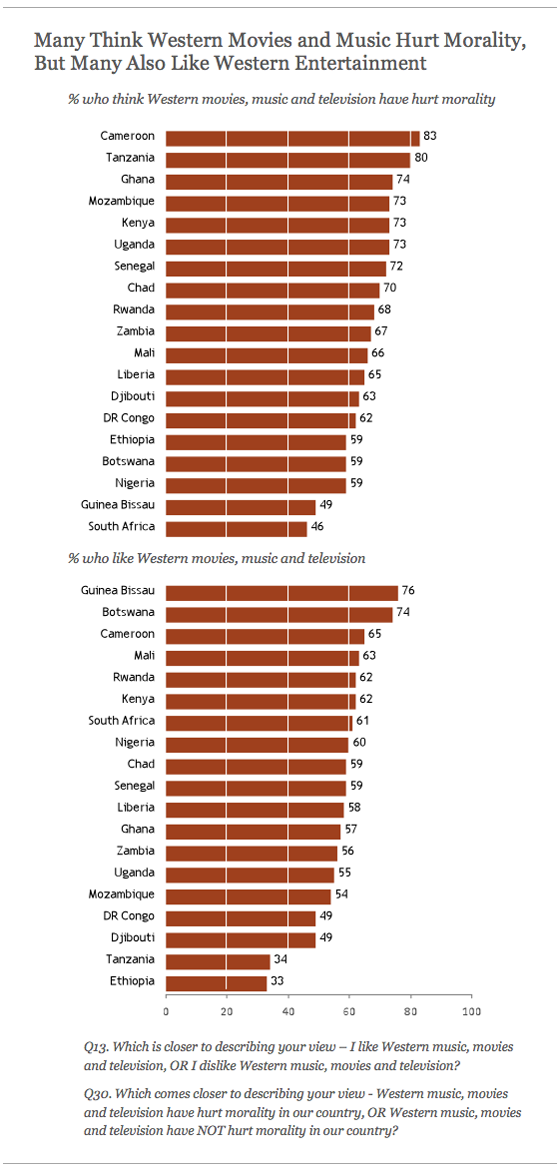

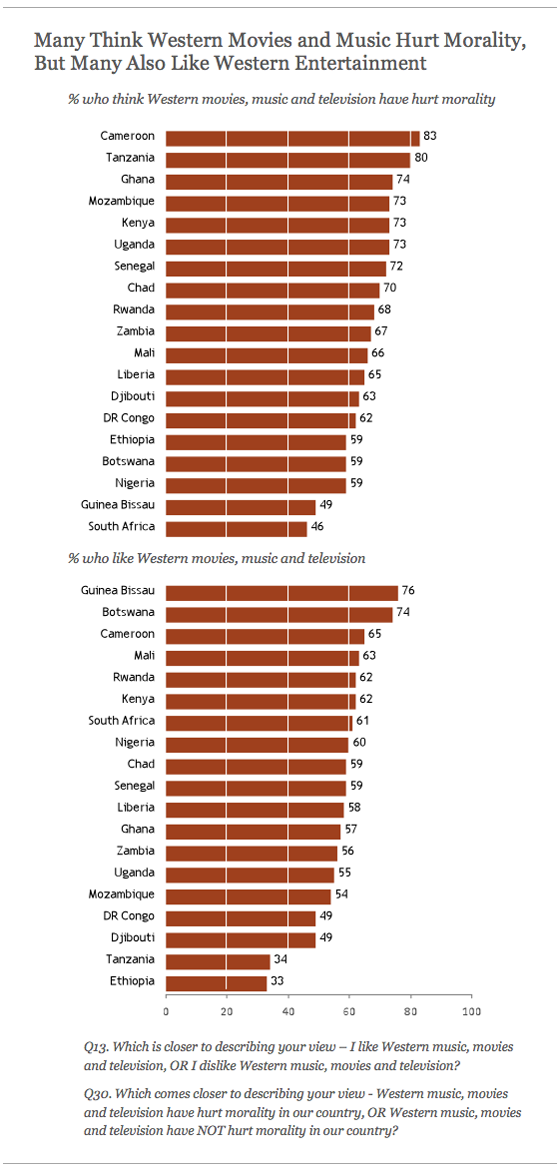

- Majorities in almost every country say that Western music, movies and television have harmed morality in their nation. Yet majorities in most countries also say they personally like Western entertainment.

- In most countries, more than half of Christians believe in the prosperity gospel – that God will grant wealth and good health to people who have enough faith.

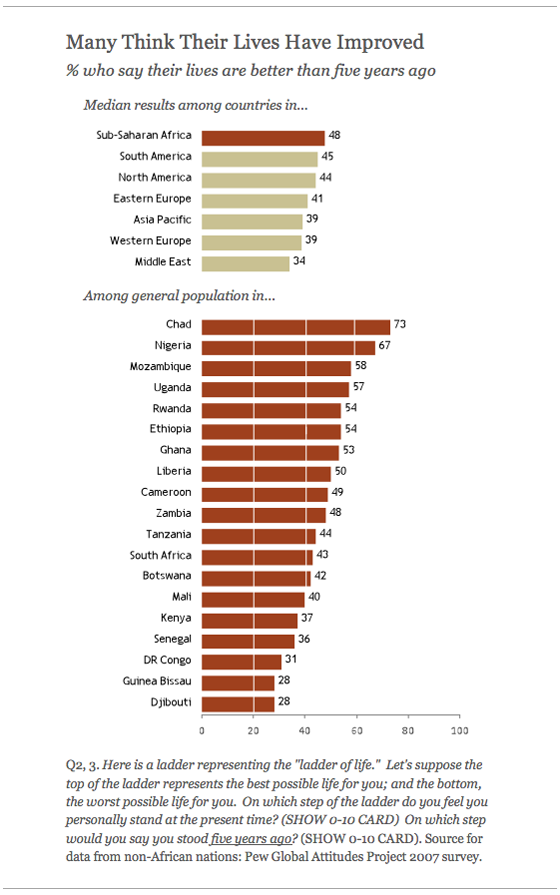

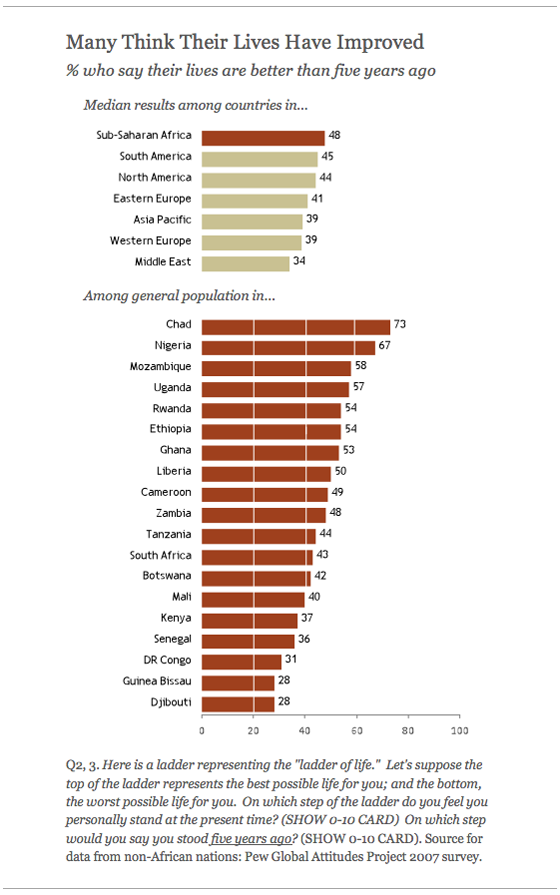

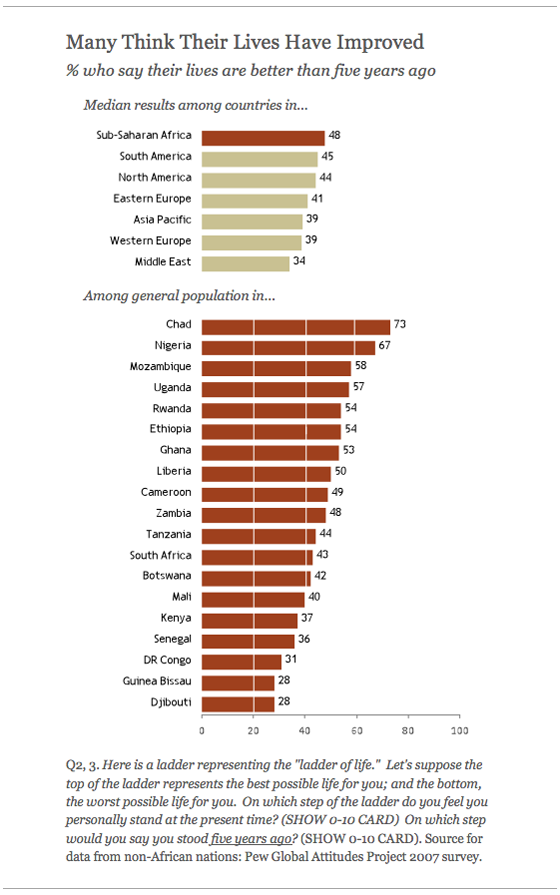

- By comparison with people in many other regions of the world, sub-Saharan Africans are much more optimistic that their lives will change for the better.

Adherence to Islam and Christianity

Large majorities in all the countries surveyed say they believe in one God and in heaven and hell, and large numbers of Christians and Muslims alike believe in the literal truth of their scriptures (either the Bible or the Koran). Most people also say they attend worship services at least once a week, pray every day (in the case of Muslims, generally five times a day), fast during the holy periods of Ramadan or Lent, and give religious alms (tithing for Christians, zakat for Muslims; see the glossary of terms for more information about tithing and zakat).

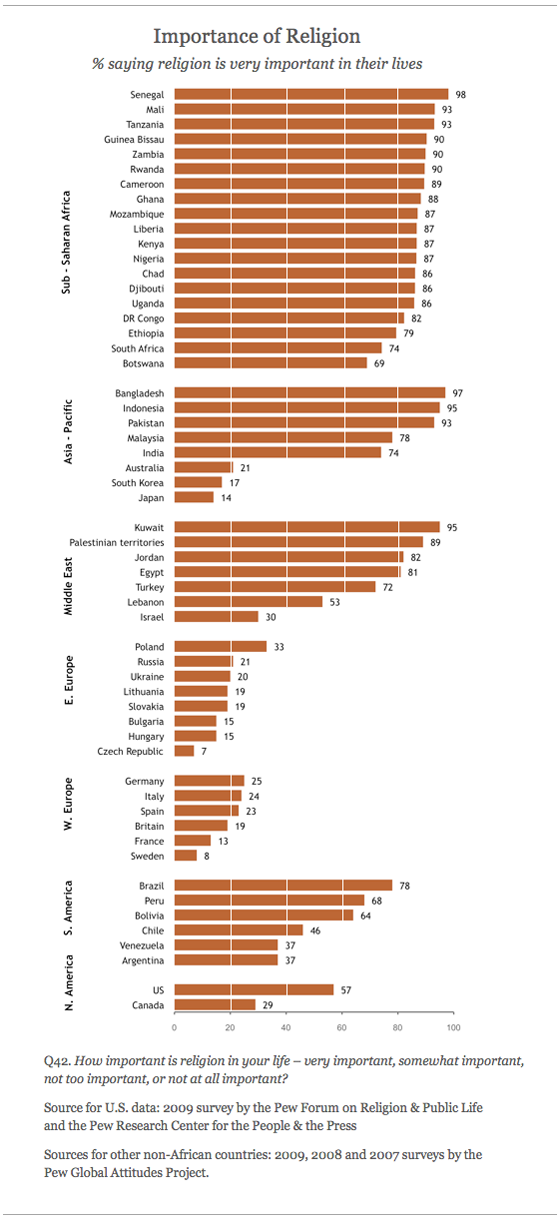

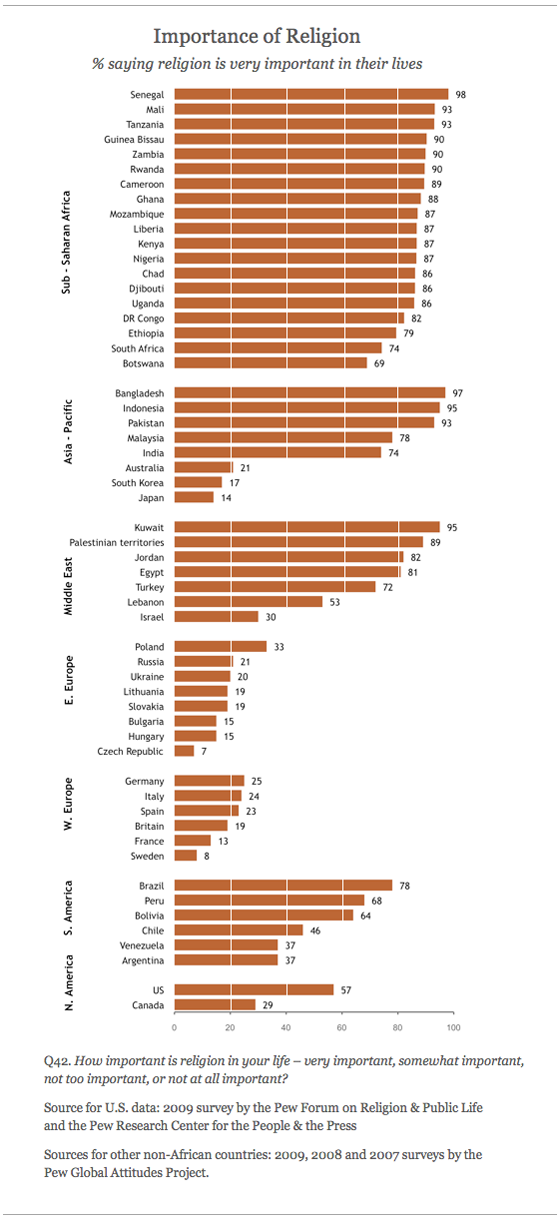

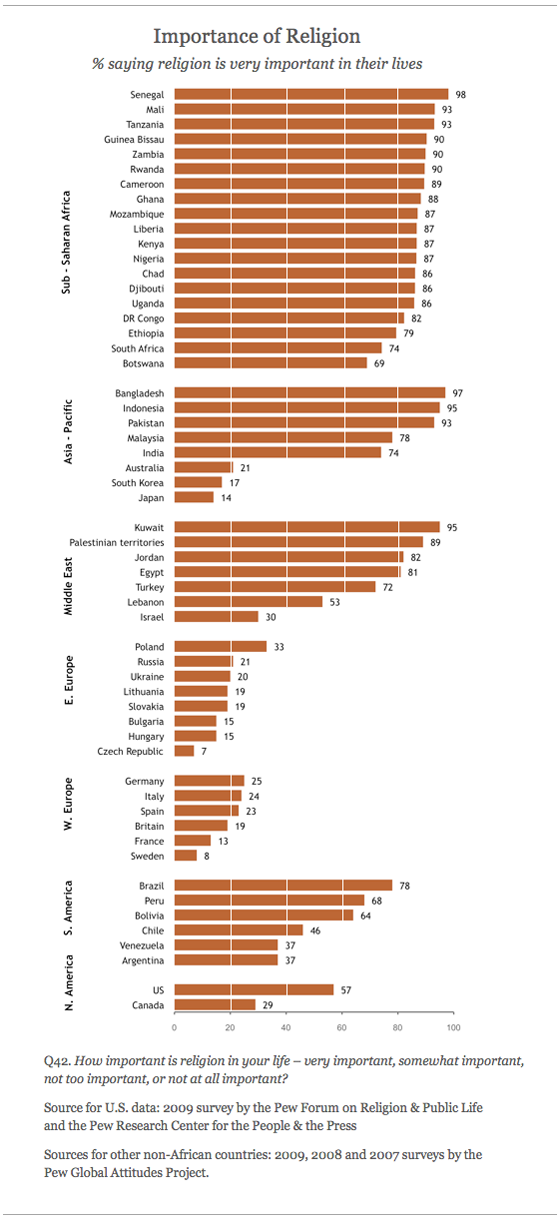

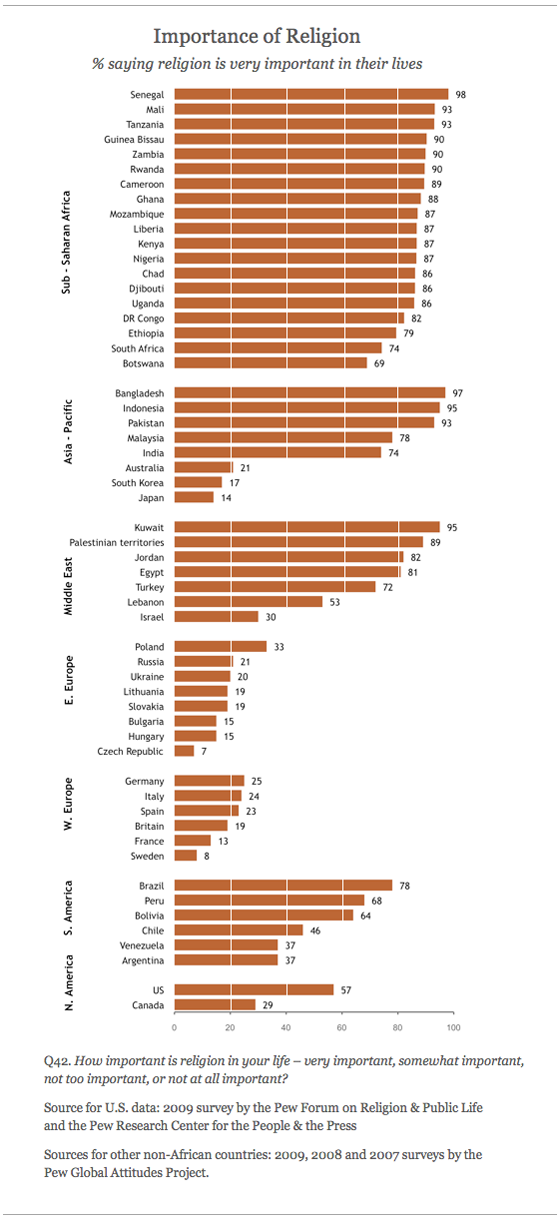

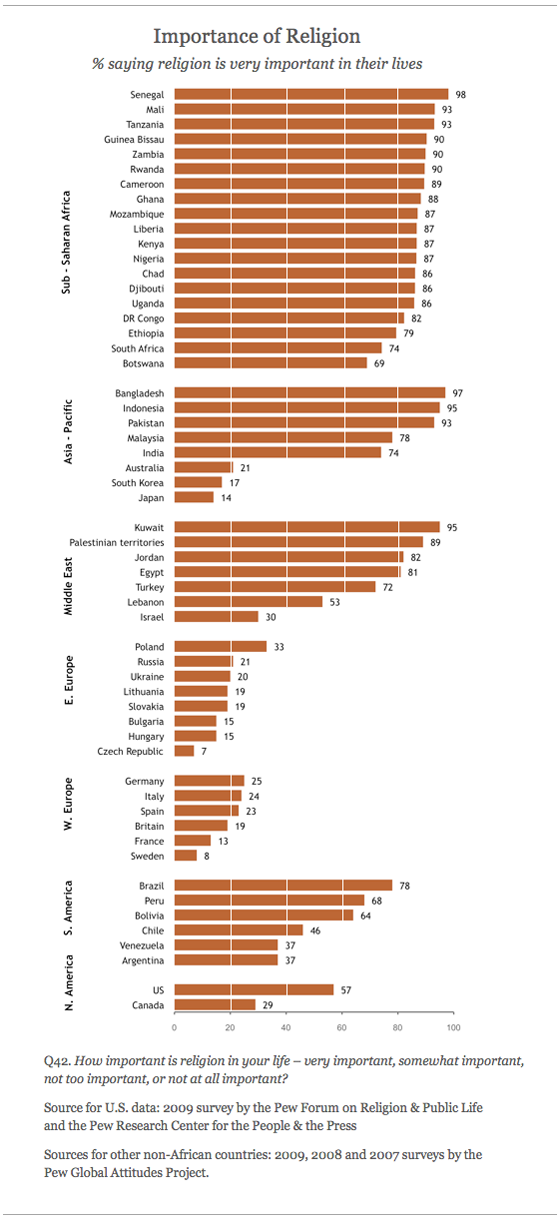

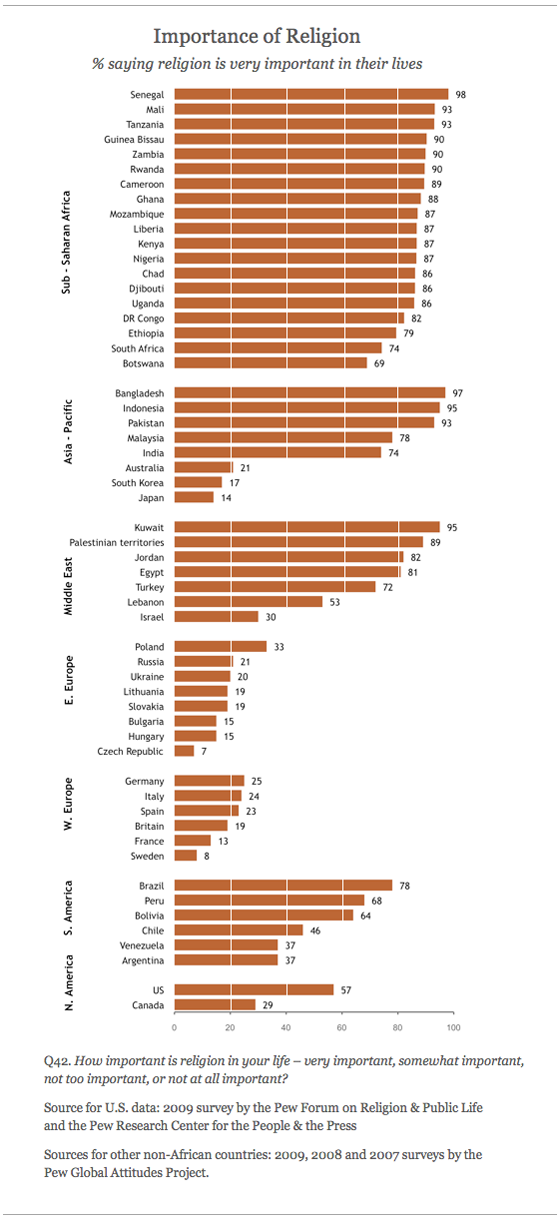

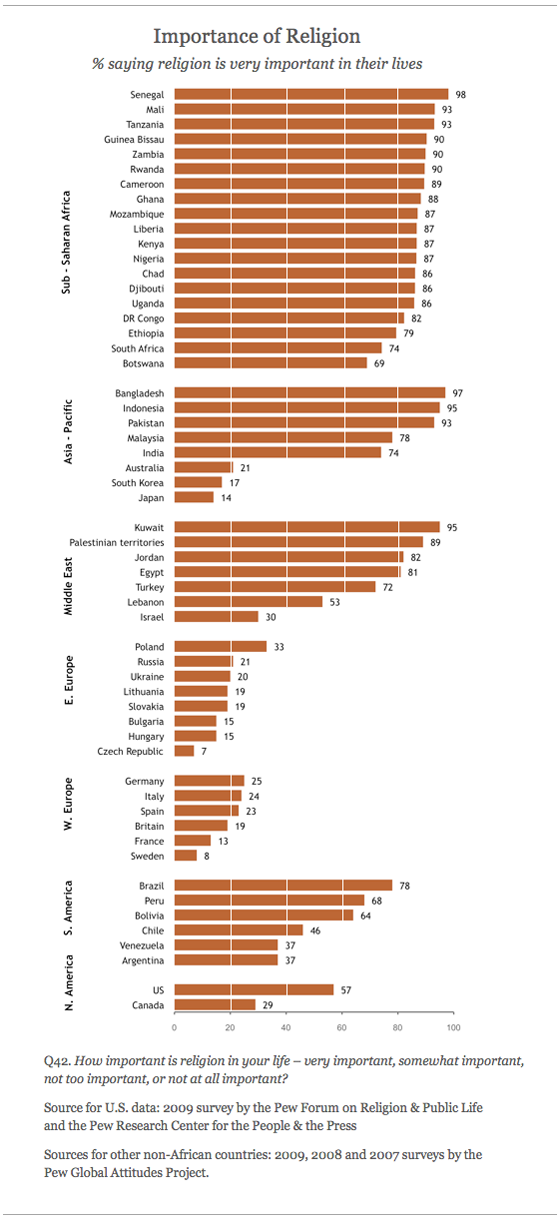

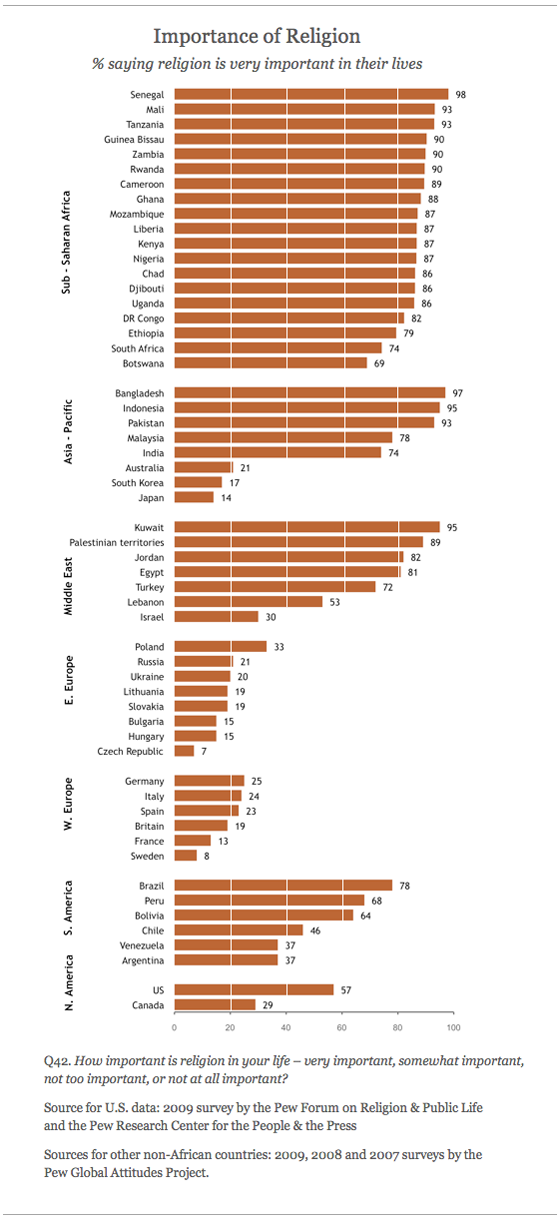

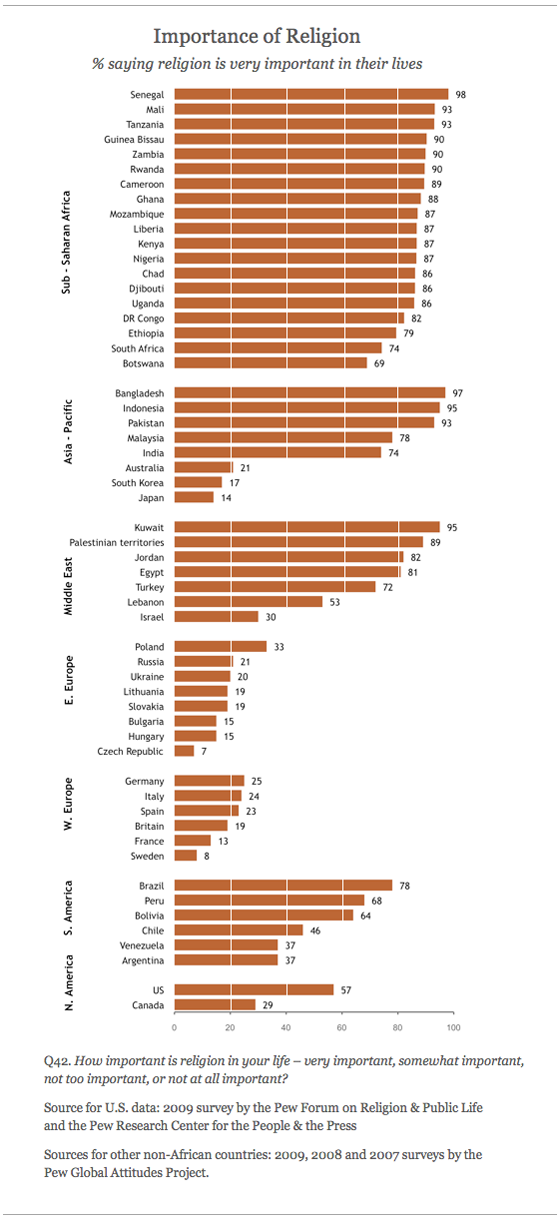

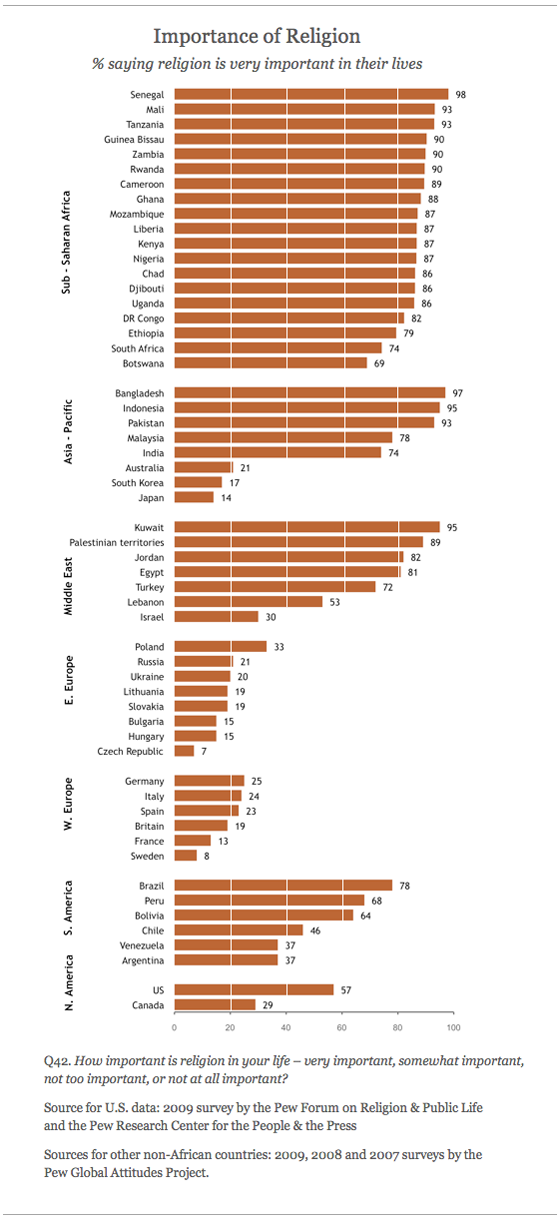

Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa is clearly among the most religious places in the world. In many countries across the continent, roughly nine-in-ten people or more say religion is very important in their lives. By this key measure, even the least religiously inclined nations in the region score higher than the United States, which is among the most religious of the advanced industrial countries.

Persistence of Traditional African Religious Practices

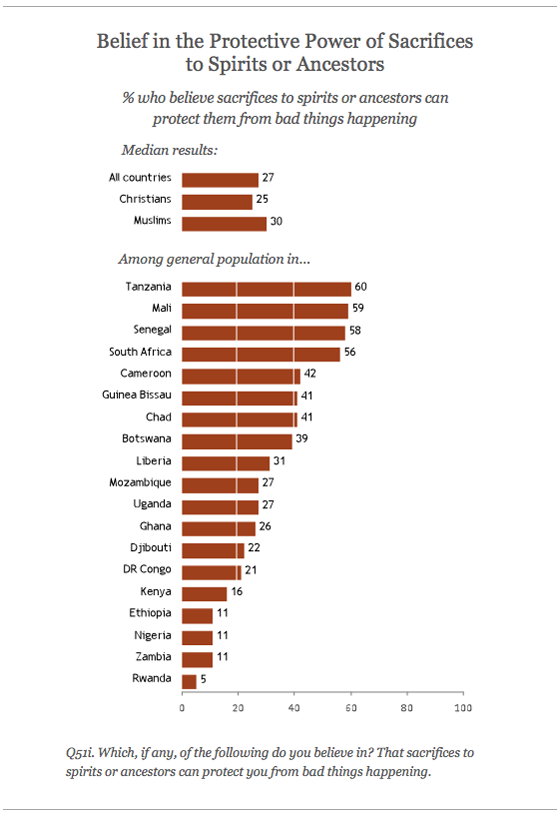

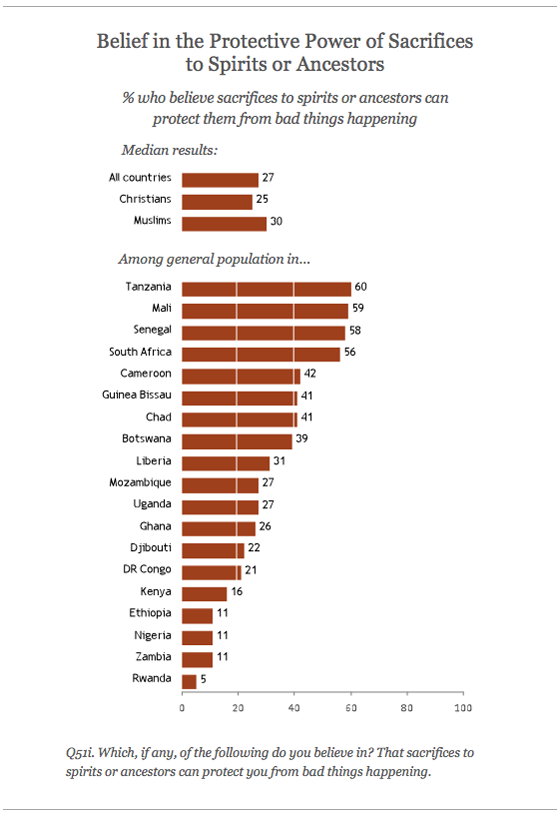

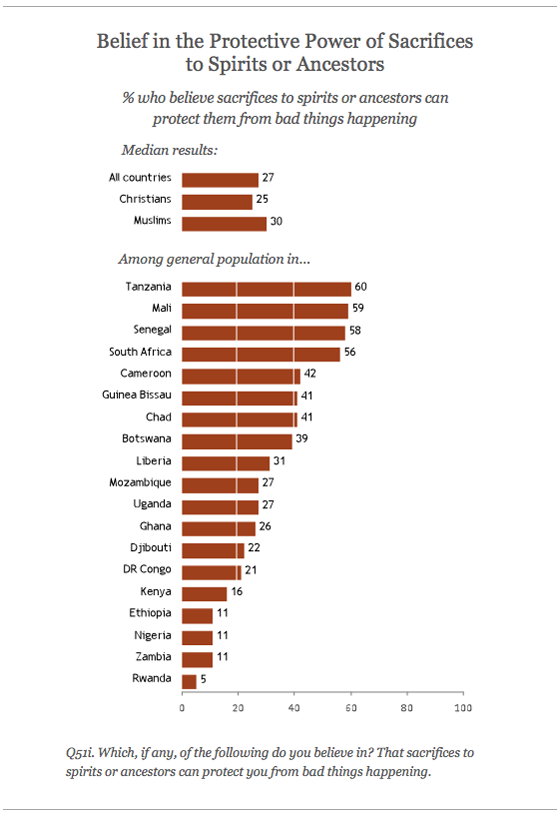

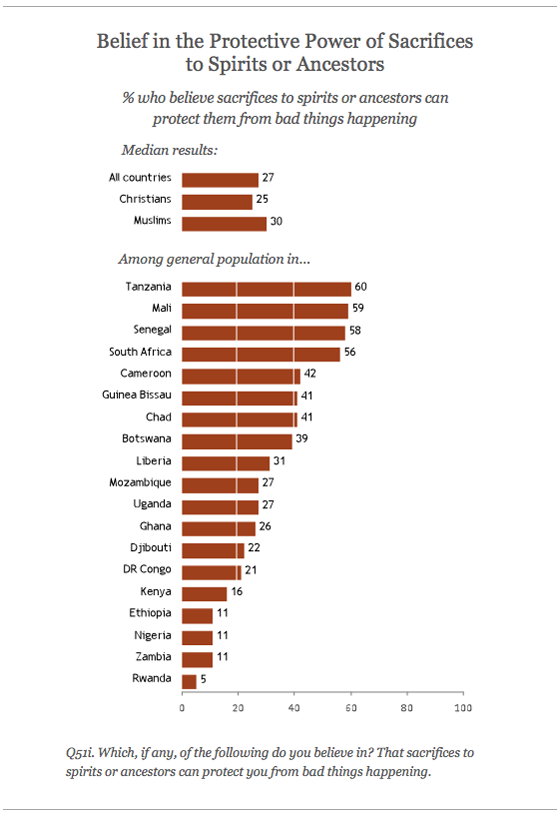

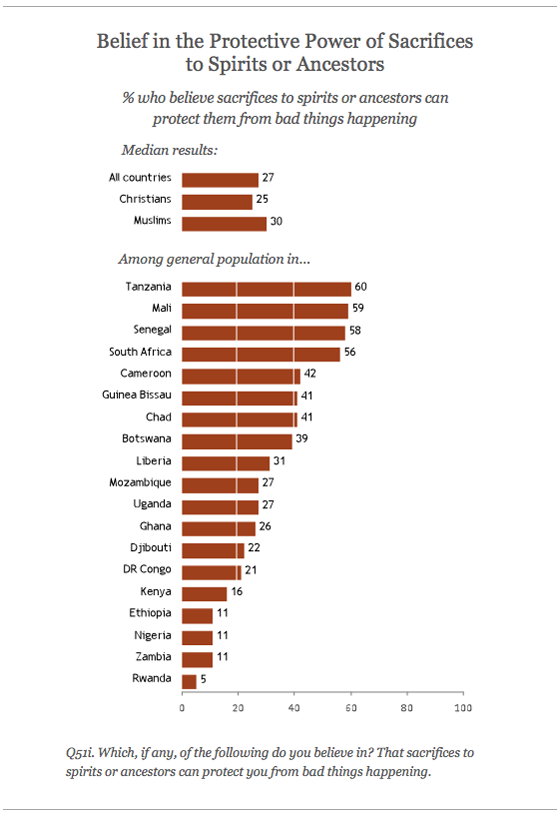

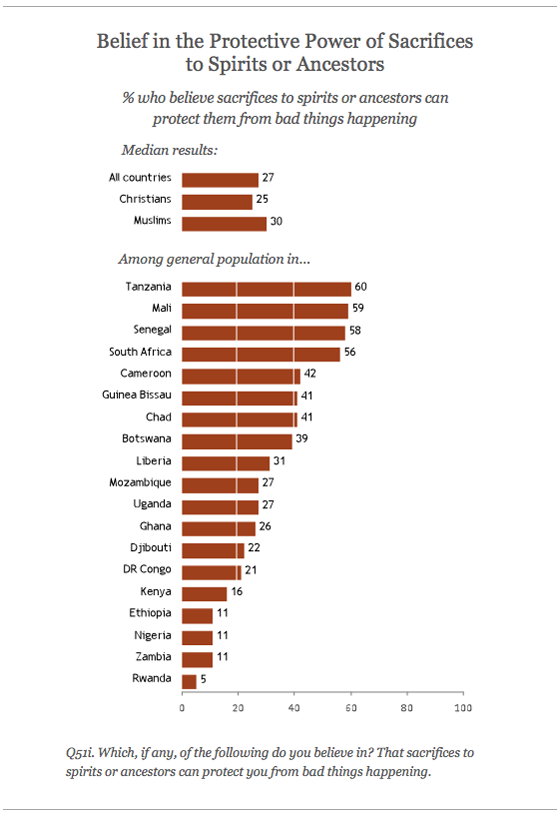

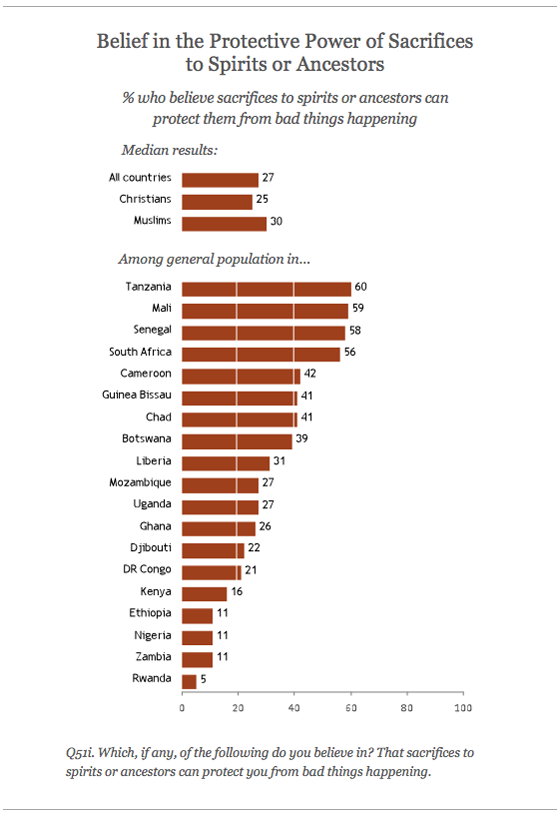

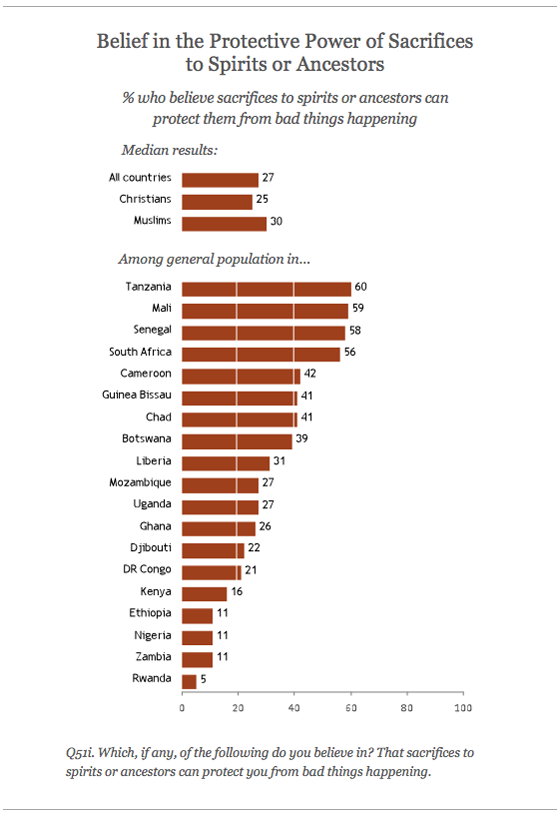

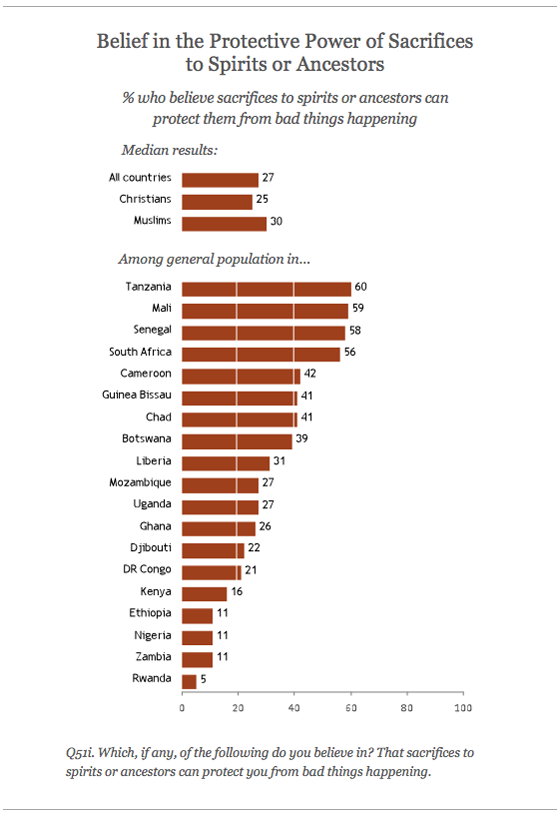

At the same time, many of those who indicate they are deeply committed to the practice of Christianity or Islam also incorporate elements of African traditional religions into their daily lives. For example, in four countries (Tanzania, Mali, Senegal and South Africa) more than half the people surveyed believe that sacrifices to ancestors or spirits can protect them from harm.

Sizable percentages of both Christians and Muslims – a quarter or more in many countries – say they believe in the protective power of juju (charms or amulets). Many people also say they consult traditional religious healers when someone in their household is sick, and sizable minorities in several countries keep sacred objects such as animal skins and skulls in their homes and participate in ceremonies to honor their ancestors. And although relatively few people today identify themselves primarily as followers of a traditional African religion, many people in several countries say they have relatives who identify with these traditional faiths.

| Quick Definition: African Traditional Religions |

Handed down over generations, indigenous African religions have no formal creeds or sacred texts comparable to the Bible or Koran. They find expression, instead, in oral traditions, myths, rituals, festivals, shrines, art and symbols. In the past, Westerners sometimes described them as animism, paganism, ancestor worship or simply superstition, but today scholars acknowledge the existence of sophisticated African traditional religions whose primary role is to provide for human well-being in the present as opposed to offering salvation in a future world.

Because beliefs and practices vary across ethnic groups and regions, some experts perceive a multitude of different traditional religions in Africa. Others point to unifying themes and, thus, prefer to think of a single faith with local differences.

In general, traditional religion in Africa is characterized by belief in a supreme being who created and ordered the world but is often experienced as distant or unavailable to humans. Lesser divinities or spirits who are more accessible are sometimes believed to act as intermediaries. A number of traditional myths explain the creation and ordering of the world and provide explanations for contemporary social relationships and norms. Lapsed social responsibilities or violations of taboos are widely believed to result in hardship, suffering and illness for individuals or communities and must be countered with ritual acts to re-establish order, harmony and well-being.

Ancestors, considered to be in the spirit world, are believed to be part of the human community. Believers hold that ancestors sometimes act as emissaries between living beings and the divine, helping to maintain social order and withdrawing their support if the living behave wrongly. Religious specialists, such as diviners and healers, are called upon to discern what infractions are at the root of misfortune and to prescribe the appropriate rituals or traditional medicines to set things right.

African traditional religions tend to personify evil. Believers often blame witches or sorcerers for attacking their life-force, causing illness or other harm. They seek to protect themselves with ritual acts, sacred objects and traditional medicines. African slaves carried these beliefs and practices to the Americas, where they have evolved into religions such as Voodoo in Haiti and Santeria in Cuba. (back to text)

Tolerance, but Also Tensions

The survey finds that on several measures, many Muslims and Christians hold favorable views of each other. Muslims generally say Christians are tolerant, honest and respectful of women, and in most countries half or more Christians say Muslims are honest, devout and respectful of women. In roughly half the countries surveyed, majorities also say they trust people who have different religious values than their own.

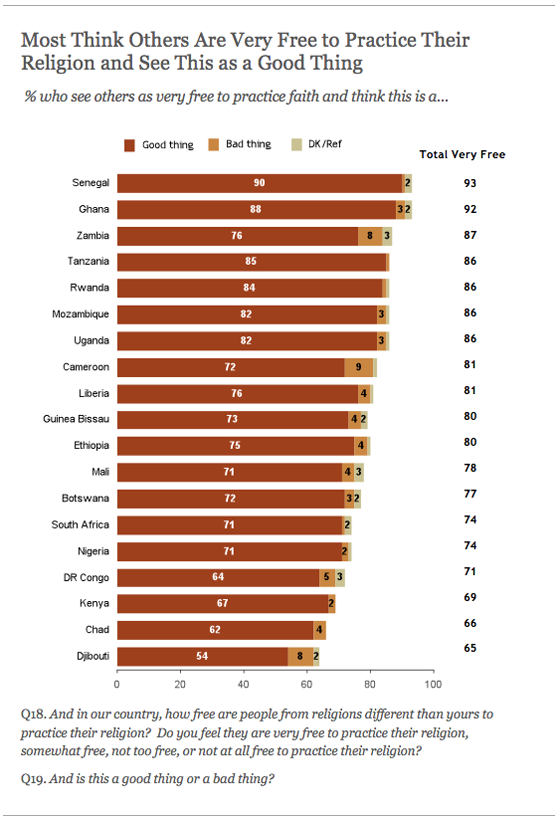

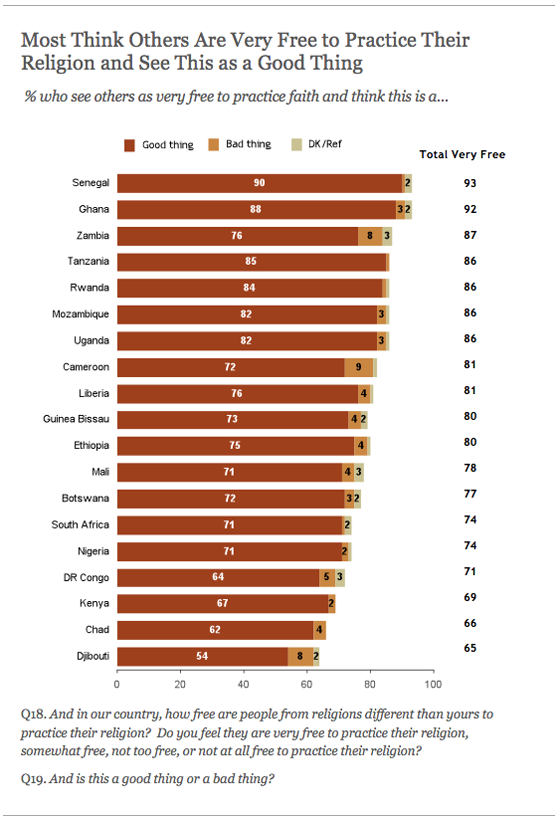

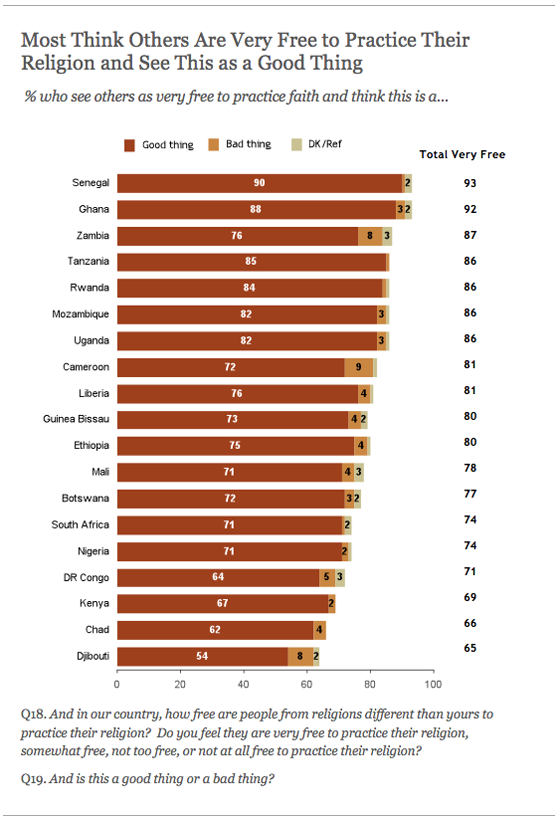

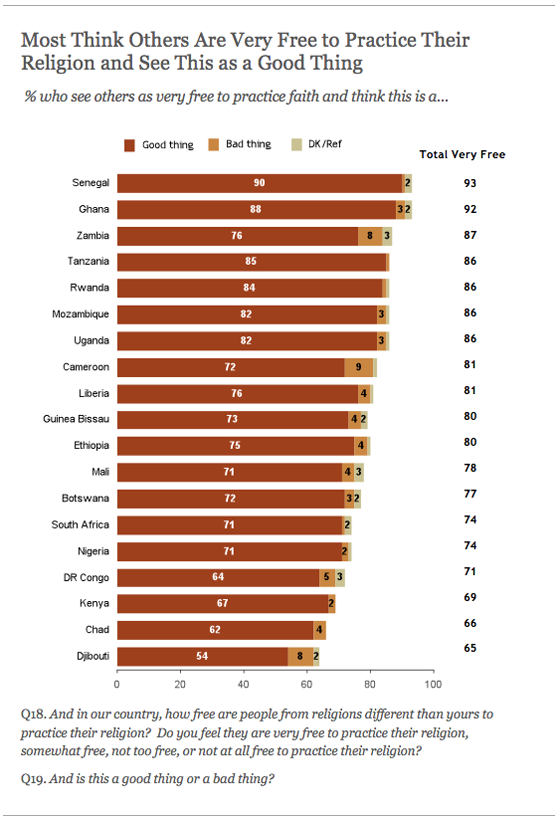

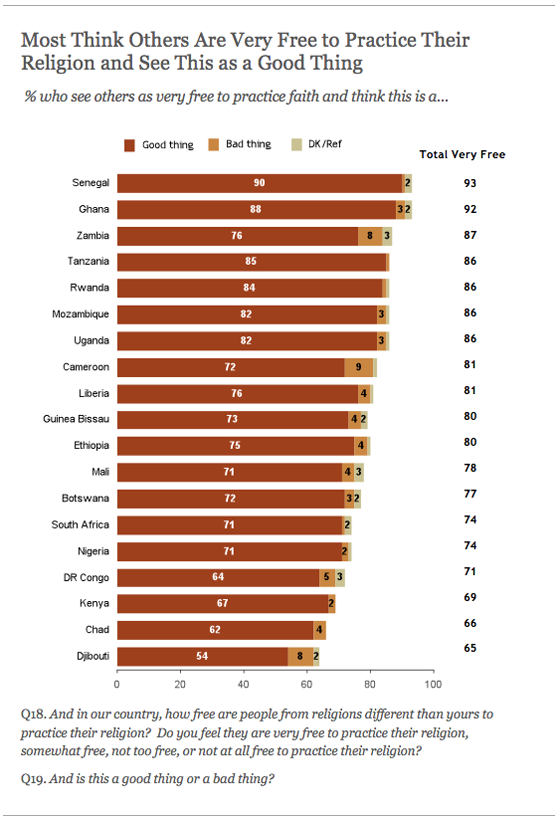

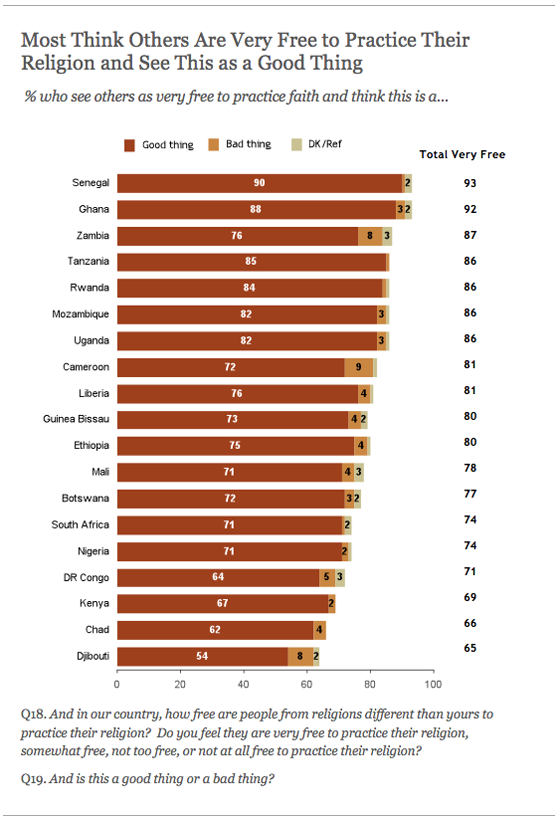

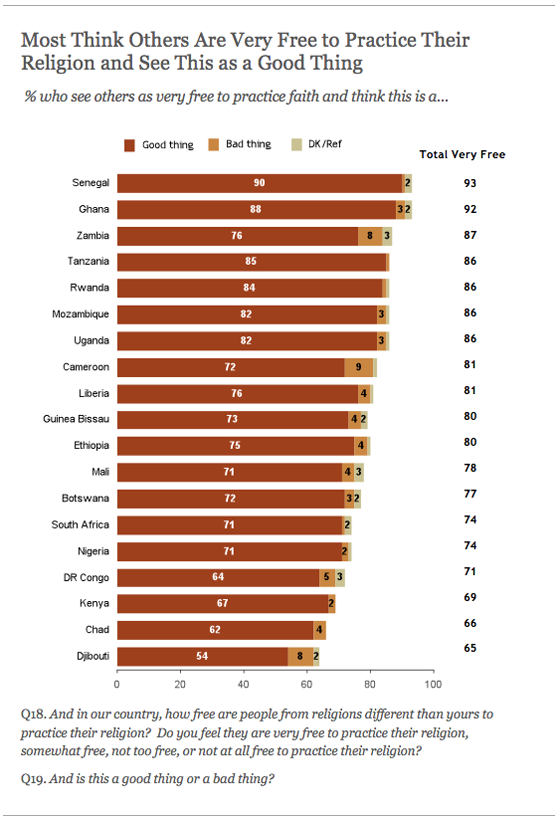

Sizable majorities in every country surveyed say that people of different faiths are very free to practice their religion, and most add that this is a good thing rather than a bad thing. In most countries, majorities say it is all right if their political leaders are of a different religion than their own. And in most countries, significant minorities (20% or more) of people who attend religious services say that their mosque or church works across religious lines to address community problems.

On the other hand, the survey also reveals clear signs of tension and division. Overall, Christians are less positive in their views of Muslims than Muslims are of Christians; substantial numbers of Christians (ranging from 20% in Guinea Bissau to 70% in Chad) say they think of Muslims as violent. In a handful of countries, a third or more of Christians say many or most Muslims are hostile toward Christians, and in a few countries a third or more of Muslims say many or most Christians are hostile toward Muslims.

The median is the middle number in a list of numbers sorted from highest to lowest. For many questions in this report, medians are shown to help readers see differences between Muslim and Christian subpopulations and general populations, or to highlight differences between sub-Saharan Africa and other parts of the world.

In charts showing results from all 19 countries on a particular question, the median for “all countries” is the 10th spot on the list. In charts where there is an even number of countries in the list and there is no country exactly in the middle, the median is computed as the average of the two countries at the middle of the list (e.g., where 16 nations are shown, the median is the average of the 8th and 9th countries on the list).

To help readers see whether Muslims and Christians differ significantly on certain questions, separate medians for Christians and Muslims also are shown. The median for Christians is based on the survey results among Christians in each of the 16 countries with a Christian population large enough to analyze. The median for Muslims is based on the survey results among Muslims in each of the 15 countries with a Muslim population large enough to analyze.

By their own reckoning, neither Christians nor Muslims in the region know very much about each other’s faith. In most countries, fewer than half of Christians say they know either some or a great deal about Islam, and fewer than half of Muslims say they know either some or a great deal about Christianity. Moreover, people in most countries surveyed, especially Christians, tend to view the two faiths as very different rather than as having a lot in common. And many people say they are not comfortable with the idea of their children marrying a spouse from outside their religion.

People throughout the region generally see conflict between religious groups as a modest problem compared with other issues such as unemployment, crime and corruption. Still, substantial numbers in all the countries surveyed except Botswana and Zambia say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country, reaching a high of 58% in Nigeria and Rwanda. In addition, substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say that violence against civilians in defense of one’s religion can sometimes or often be justified. And large numbers (more than 40%) in nearly every country express concern about extremist religious groups in their nation, including within their own religious community in some instances. Indeed, in almost all countries in which Muslims constitute at least 10% of the population, Muslims are more concerned about Muslim extremism than they are about Christian extremism, while in a few overwhelmingly Christian countries, including South Africa, Christians are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism. And in many countries, sizable numbers express concern about both Muslim and Christian extremism.

Support for Both Democracy and Religious Law

Across the sub-Saharan region, large numbers of people express strong support for democracy and say it is a good thing that people from religions different than their own are able to practice their faith freely. Asked whether democracy is preferable to any other kind of government or “in some circumstances, a nondemocratic government can be preferable,” strong majorities in every country choose democracy. In most places there is no significant difference between Muslims and Christians on this question.

At the same time, there is substantial backing from both Muslims and Christians for basing civil laws on the Bible or sharia law. This may simply reflect the importance of religion in Africa. But it is nonetheless striking that in virtually all the countries surveyed, a majority or substantial minority (a third or more) of Christians favor making the Bible the official law of the land, while similarly large numbers of Muslims say they would like to enshrine sharia, or Islamic law.

Majorities of Muslims in nearly all the countries surveyed support allowing leaders and judges to use their religious beliefs when deciding family and property disputes, as do sizable minorities (30% or more) of Christians in most countries. Similarly, the survey finds considerable support among Muslims in several countries for the application of criminal sanctions such as stoning people who commit adultery, and whipping or cutting off the hands of thieves. Support for these kinds of punishments is consistently lower among Christians than among Muslims. The survey also finds that in seven countries, roughly one-third or more of Muslims say they support the death penalty for those who leave Islam.

The End of Christian and Muslim Expansion?

While the survey finds that both Christianity and Islam are flourishing in sub-Saharan Africa, the results suggest that neither faith may expand as rapidly in this region in the years ahead as it did in the 20th century, except possibly through natural population growth. There are two main reasons for this conclusion. First, the survey shows that most people in the region have committed to Christianity or Islam, which means the pool of potential converts from outside these two faiths has decreased dramatically. In most countries surveyed, 90% or more describe themselves as either Christians or Muslims, meaning that fewer than one-in-ten identify as adherents of other faiths (including African traditional religions) or no faith.

Second, there is little evidence in the survey findings to indicate that either Christianity or Islam is growing in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other. Although a relatively small percentage of Muslims have become Christians, and a relatively small percentage of Christians have become Muslims, the survey finds no substantial shift in either direction. One exception is Uganda, where roughly one-third of respondents who were raised Muslim now describe themselves as Christian, while far fewer Ugandans who were raised Christian now describe themselves as Muslim.

Intense Religious Experiences and the Influence of Pentecostalism

Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa experience their respective faiths in a very intense, immediate, personal way. For example, three-in-ten or more of the people in many countries say they have experienced a divine healing, witnessed the devil being driven out of a person or received a direct revelation from God. Moreover, in every country surveyed that has a substantial Christian population, at least half of Christians expect that Jesus will return to earth during their lifetime. And in every country surveyed that has a substantial Muslim population, roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to personally witness the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule that followed the death of Muhammad.

Many of these intense religious experiences, including divine healings and exorcisms, are also characteristic of traditional African religions. Within Christianity, these kinds of experiences are particularly associated with Pentecostalism, which emphasizes such gifts of the Holy Spirit as speaking in tongues, giving or interpreting prophecy, receiving direct revelations from God, exorcising evil and healing through prayer. About a quarter of all Christians in four sub-Saharan countries (Ethiopia, Ghana, Liberia and Nigeria) now belong to Pentecostal denominations, as do at least one-in-ten Christians in eight other countries. But the survey finds that divine healings, exorcisms and direct revelations from God are commonly reported by African Christians who are not affiliated with Pentecostal churches.

Morality and Culture

In nearly all the countries surveyed, large majorities believe it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values. Clear majorities in almost every country believe that Western music, movies and television have hurt moral standards. South Africa and Guinea Bissau are the only exceptions to this finding, and even in those nations a plurality of the survey respondents view Western entertainment as exerting a harmful moral influence. On the other hand, majorities in most countries say they personally like Western TV, movies and music, with Christians particularly inclined to say so. And in many countries, people are more inclined to say there is not a conflict between being a devout religious person and living in modern society than to say there is a conflict.

Throughout sub-Saharan Africa, Christians and Muslims alike express strong opposition to homosexual behavior, abortion, prostitution and sex between unmarried people. There are, however, pronounced differences between the two religious groups on the question of polygamy. Muslims are much more inclined than Christians to approve of polygamy or say this is not a moral issue.

Optimism and Progress

Sub-Saharan Africans commonly cite unemployment as a major problem. In most countries, more than half of the people surveyed say they are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their country. And compared with people surveyed in 2007 in other regions of the world, somewhat fewer sub-Saharan Africans today indicate they are highly satisfied with their lives. At least 30% in every country say there have been times in the last year when they did not have enough money to buy food for their families. And yet, many sub-Saharan Africans say their lives have improved over the past five years. In fact, the percentage of sub-Saharan Africans who indicate in 2009 that their lives have improved over the preceding five years rivals or exceeds the number of people in many other regions of the world who said the same in 2007. And people in the African countries surveyed are more likely than people in many other regions to express optimism that their lives will improve in the future.

About the Report

These and other findings are discussed in more detail in the remainder of this report, which is divided into five main sections:

This report also includes a glossary of key terms, a description of the methods used for this survey, and a topline including full question wording and survey results.

The survey was conducted among at least 1,000 respondents in each of the 19 countries. In three predominantly Muslim countries (Djibouti, Mali and Senegal), there were too few interviews with Christian respondents to be able to analyze the Christian subpopulation. In four predominantly Christian countries (Botswana, Rwanda, South Africa and Zambia), there were too few interviews with Muslims to be able to analyze the Muslim subpopulation. This leaves 12 countries in which comparisons between Christians and Muslims are possible.

Readers should note that the 19 national polls on which this report is based were not designed to provide detailed demographic profiles of households in each country. Rather, the survey aims to compare the views of different religious groups and the general population of the countries on a wide variety of questions concerning religious beliefs and practices as well as religion’s role in society. In other studies, such as “Mapping the Global Muslim Population” (2009), the Pew Forum provides estimates of the religious composition of countries in Africa and elsewhere based on very large datasets (such as national censuses and demographic and health surveys) that sometimes differ from the population figures presented here. An appendix (PDF) provides comparative estimates of religious composition from some recent surveys and censuses.

Download the full executive summary (18-page PDF, 1MB)

Footnotes

1 The 15% estimate is based on data from the Pew Forum’s 2009 report, “Mapping the Global Muslim Population“; other estimates based on data from the World Religion Database. (back to text)

2 Read a 2009 Pew Forum analysis of the extent to which Americans also mix and match elements of diverse religious traditions. (back to text)

Photo credit: Sebastien Desarmaux/GODONG/Godong/Corbis

Part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world's Muslims (15%).1

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort - the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - that aims to increase people's knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world's Muslims (15%).1

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort - the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - that aims to increase people's knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

Executive Summary

The vast majority of people in many sub-Saharan African nations are deeply committed to the practices and major tenets of one or the other of the world's two largest religions, Christianity and Islam. Large majorities say they belong to one of these faiths, and, in sharp contrast with Europe and the United States, very few people are religiously unaffiliated. Despite the dominance of Christianity and Islam, traditional African religious beliefs and practices have not disappeared. Rather, they coexist with Islam and Christianity. Whether or not this entails some theological tension, it is a reality in people's lives: Large numbers of Africans actively participate in Christianity or Islam yet also believe in witchcraft, evil spirits, sacrifices to ancestors, traditional religious healers, reincarnation and other elements of traditional African religions.2

Christianity and Islam also coexist with each other. Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa describe members of the other faith as tolerant and honest. In most countries, relatively few see evidence of widespread anti-Muslim or anti-Christian hostility, and on the whole they give their governments high marks for treating both religious groups fairly. But they acknowledge that they know relatively little about each other's faith, and substantial numbers of African Christians (roughly 40% or more in a dozen nations) say they consider Muslims to be violent. Muslims are significantly more positive in their assessment of Christians than Christians are in their assessment of Muslims.

There are few significant gaps, however, in the degree of support among Christians and Muslims for democracy. Regardless of their faith, most sub-Saharan Africans say they favor democracy and think it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, there is substantial backing among Muslims and Christians alike for government based on either the Bible or sharia law, and considerable support among Muslims for the imposition of severe punishments such as stoning people who commit adultery.

These are among the key findings from more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews conducted on behalf of the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 sub-Saharan African nations from December 2008 to April 2009. (For additional details, see the survey methodology (PDF).) The countries were selected to span this vast geographical region and to reflect different colonial histories, linguistic backgrounds and religious compositions. In total, the countries surveyed contain three-quarters of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa.

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world's Muslims (15%).1

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort - the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - that aims to increase people's knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

Executive Summary

The vast majority of people in many sub-Saharan African nations are deeply committed to the practices and major tenets of one or the other of the world's two largest religions, Christianity and Islam. Large majorities say they belong to one of these faiths, and, in sharp contrast with Europe and the United States, very few people are religiously unaffiliated. Despite the dominance of Christianity and Islam, traditional African religious beliefs and practices have not disappeared. Rather, they coexist with Islam and Christianity. Whether or not this entails some theological tension, it is a reality in people's lives: Large numbers of Africans actively participate in Christianity or Islam yet also believe in witchcraft, evil spirits, sacrifices to ancestors, traditional religious healers, reincarnation and other elements of traditional African religions.2

Christianity and Islam also coexist with each other. Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa describe members of the other faith as tolerant and honest. In most countries, relatively few see evidence of widespread anti-Muslim or anti-Christian hostility, and on the whole they give their governments high marks for treating both religious groups fairly. But they acknowledge that they know relatively little about each other's faith, and substantial numbers of African Christians (roughly 40% or more in a dozen nations) say they consider Muslims to be violent. Muslims are significantly more positive in their assessment of Christians than Christians are in their assessment of Muslims.

There are few significant gaps, however, in the degree of support among Christians and Muslims for democracy. Regardless of their faith, most sub-Saharan Africans say they favor democracy and think it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, there is substantial backing among Muslims and Christians alike for government based on either the Bible or sharia law, and considerable support among Muslims for the imposition of severe punishments such as stoning people who commit adultery.

These are among the key findings from more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews conducted on behalf of the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 sub-Saharan African nations from December 2008 to April 2009. (For additional details, see the survey methodology (PDF).) The countries were selected to span this vast geographical region and to reflect different colonial histories, linguistic backgrounds and religious compositions. In total, the countries surveyed contain three-quarters of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa.

Other Findings

In addition, the 19-nation survey finds:

-

- Africans generally rank unemployment, crime and corruption as bigger problems than religious conflict. However, substantial numbers of people (including nearly six-in-ten Nigerians and Rwandans) say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country.

- The degree of concern about religious conflict varies from country to country but tracks closely with the degree of concern about ethnic conflict in many countries, suggesting that they are often related.

- Many Africans are concerned about religious extremism, including within their own faith. Indeed, many Muslims say they are more concerned about Muslim extremism than about Christian extremism, and Christians in four countries say they are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism.

- Neither Christianity nor Islam is growing significantly in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other; there is virtually no net change in either direction through religious switching.

- At least half of all Christians in every country surveyed expect that Jesus will return to earth in their lifetime, while roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to live to see the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule.

- People who say violence against civilians in defense of one's religion is rarely or never justified vastly outnumber those who say it is sometimes or often justified. But substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say violence against civilians in defense of one's religion is sometimes or often justified.

- In most countries, at least half of Muslims say that women should not have the right to decide whether to wear a veil, saying instead that the decision should be up to society as a whole.

- Circumcision of girls (female genital cutting) is highest in the predominantly Muslim countries of Mali and Djibouti but is more common among Christians than among Muslims in Uganda.

- Majorities in almost every country say that Western music, movies and television have harmed morality in their nation. Yet majorities in most countries also say they personally like Western entertainment.

- In most countries, more than half of Christians believe in the prosperity gospel - that God will grant wealth and good health to people who have enough faith.

- By comparison with people in many other regions of the world, sub-Saharan Africans are much more optimistic that their lives will change for the better.

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world's Muslims (15%).1

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort - the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - that aims to increase people's knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

Executive Summary

The vast majority of people in many sub-Saharan African nations are deeply committed to the practices and major tenets of one or the other of the world's two largest religions, Christianity and Islam. Large majorities say they belong to one of these faiths, and, in sharp contrast with Europe and the United States, very few people are religiously unaffiliated. Despite the dominance of Christianity and Islam, traditional African religious beliefs and practices have not disappeared. Rather, they coexist with Islam and Christianity. Whether or not this entails some theological tension, it is a reality in people's lives: Large numbers of Africans actively participate in Christianity or Islam yet also believe in witchcraft, evil spirits, sacrifices to ancestors, traditional religious healers, reincarnation and other elements of traditional African religions.2

Christianity and Islam also coexist with each other. Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa describe members of the other faith as tolerant and honest. In most countries, relatively few see evidence of widespread anti-Muslim or anti-Christian hostility, and on the whole they give their governments high marks for treating both religious groups fairly. But they acknowledge that they know relatively little about each other's faith, and substantial numbers of African Christians (roughly 40% or more in a dozen nations) say they consider Muslims to be violent. Muslims are significantly more positive in their assessment of Christians than Christians are in their assessment of Muslims.

There are few significant gaps, however, in the degree of support among Christians and Muslims for democracy. Regardless of their faith, most sub-Saharan Africans say they favor democracy and think it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, there is substantial backing among Muslims and Christians alike for government based on either the Bible or sharia law, and considerable support among Muslims for the imposition of severe punishments such as stoning people who commit adultery.

These are among the key findings from more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews conducted on behalf of the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 sub-Saharan African nations from December 2008 to April 2009. (For additional details, see the survey methodology (PDF).) The countries were selected to span this vast geographical region and to reflect different colonial histories, linguistic backgrounds and religious compositions. In total, the countries surveyed contain three-quarters of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa.

Other Findings

In addition, the 19-nation survey finds:

-

- Africans generally rank unemployment, crime and corruption as bigger problems than religious conflict. However, substantial numbers of people (including nearly six-in-ten Nigerians and Rwandans) say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country.

- The degree of concern about religious conflict varies from country to country but tracks closely with the degree of concern about ethnic conflict in many countries, suggesting that they are often related.

- Many Africans are concerned about religious extremism, including within their own faith. Indeed, many Muslims say they are more concerned about Muslim extremism than about Christian extremism, and Christians in four countries say they are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism.

- Neither Christianity nor Islam is growing significantly in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other; there is virtually no net change in either direction through religious switching.

- At least half of all Christians in every country surveyed expect that Jesus will return to earth in their lifetime, while roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to live to see the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule.

- People who say violence against civilians in defense of one's religion is rarely or never justified vastly outnumber those who say it is sometimes or often justified. But substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say violence against civilians in defense of one's religion is sometimes or often justified.

- In most countries, at least half of Muslims say that women should not have the right to decide whether to wear a veil, saying instead that the decision should be up to society as a whole.

- Circumcision of girls (female genital cutting) is highest in the predominantly Muslim countries of Mali and Djibouti but is more common among Christians than among Muslims in Uganda.

- Majorities in almost every country say that Western music, movies and television have harmed morality in their nation. Yet majorities in most countries also say they personally like Western entertainment.

- In most countries, more than half of Christians believe in the prosperity gospel - that God will grant wealth and good health to people who have enough faith.

- By comparison with people in many other regions of the world, sub-Saharan Africans are much more optimistic that their lives will change for the better.

Adherence to Islam and Christianity

Large majorities in all the countries surveyed say they believe in one God and in heaven and hell, and large numbers of Christians and Muslims alike believe in the literal truth of their scriptures (either the Bible or the Koran). Most people also say they attend worship services at least once a week, pray every day (in the case of Muslims, generally five times a day), fast during the holy periods of Ramadan or Lent, and give religious alms (tithing for Christians, zakat for Muslims; see the glossary of terms for more information about tithing and zakat).

Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa is clearly among the most religious places in the world. In many countries across the continent, roughly nine-in-ten people or more say religion is very important in their lives. By this key measure, even the least religiously inclined nations in the region score higher than the United States, which is among the most religious of the advanced industrial countries.

In little more than a century, the religious landscape of sub-Saharan Africa has changed dramatically. As of 1900, both Muslims and Christians were relatively small minorities in the region. The vast majority of people practiced traditional African religions, while adherents of Christianity and Islam combined made up less than a quarter of the population, according to historical estimates from the World Religion Database.

Since then, however, the number of Muslims living between the Sahara Desert and the Cape of Good Hope has increased more than 20-fold, rising from an estimated 11 million in 1900 to approximately 234 million in 2010. The number of Christians has grown even faster, soaring almost 70-fold from about 7 million to 470 million. Sub-Saharan Africa now is home to about one-in-five of all the Christians in the world (21%) and more than one-in-seven of the world's Muslims (15%).1

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

While sub-Saharan Africa has almost twice as many Christians as Muslims, on the African continent as a whole the two faiths are roughly balanced, with 400 million to 500 million followers each. Since northern Africa is heavily Muslim and southern Africa is heavily Christian, the great meeting place is in the middle, a 4,000-mile swath from Somalia in the east to Senegal in the west.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To some outside observers, this is a volatile religious fault line—the site, for example, of al-Qaeda's first major terrorist strike, the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, and more recently of ethnic and sectarian bloodshed in Nigeria, where hundreds of Muslims and Christians have been killed.

To others, religion is not so much a source of conflict as a source of hope in sub- Saharan Africa, where religious leaders and movements are a major force in civil society and a key provider of relief and development for the needy, particularly given the widespread reality of failed states and collapsing government services.

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

But how do sub-Saharan Africans themselves view the role of religion in their lives and societies? To address this question, the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life, with generous funding from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, conducted a major public opinion survey involving more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 countries, representing 75% of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa. (View a PDF map of the 19 countries surveyed.)

Our survey asked people to describe their religious beliefs and practices. We sought to gauge their knowledge of, and attitudes toward, other faiths. We tried to assess their degree of political and economic satisfaction; their concerns about crime, corruption and extremism; their positions on issues such as abortion and polygamy; and their views of democracy, religious law and the place of women in society.

The resulting report offers a detailed and in some ways surprising portrait of religion and society in a wide variety of countries, some heavily Muslim, some heavily Christian and some mixed. Africans have long been seen as devout and morally conservative, and the survey largely confirms this. But insofar as the conventional wisdom has been that Africans are lacking in tolerance for people of other faiths, it may need rethinking.

The report also may pose some apparent paradoxes, at least to Western readers. The survey findings suggest that many Africans are deeply committed to Islam or Christianity and yet continue to practice elements of traditional African religions. Many support democracy and say it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, they also favor making the Bible or sharia law the official law of the land. And while both Muslims and Christians recognize positive attributes in one another, tensions lie close to the surface.

It is our hope that the survey will contribute to a better understanding of the role religion plays in the private and public lives of the approximately 820 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. This report is part of a larger effort - the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project - that aims to increase people's knowledge of religion around the world.

—Luis Lugo and Alan Cooperman

Download the full preface (5-page PDF, <1MB)

Executive Summary

The vast majority of people in many sub-Saharan African nations are deeply committed to the practices and major tenets of one or the other of the world's two largest religions, Christianity and Islam. Large majorities say they belong to one of these faiths, and, in sharp contrast with Europe and the United States, very few people are religiously unaffiliated. Despite the dominance of Christianity and Islam, traditional African religious beliefs and practices have not disappeared. Rather, they coexist with Islam and Christianity. Whether or not this entails some theological tension, it is a reality in people's lives: Large numbers of Africans actively participate in Christianity or Islam yet also believe in witchcraft, evil spirits, sacrifices to ancestors, traditional religious healers, reincarnation and other elements of traditional African religions.2

Christianity and Islam also coexist with each other. Many Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa describe members of the other faith as tolerant and honest. In most countries, relatively few see evidence of widespread anti-Muslim or anti-Christian hostility, and on the whole they give their governments high marks for treating both religious groups fairly. But they acknowledge that they know relatively little about each other's faith, and substantial numbers of African Christians (roughly 40% or more in a dozen nations) say they consider Muslims to be violent. Muslims are significantly more positive in their assessment of Christians than Christians are in their assessment of Muslims.

There are few significant gaps, however, in the degree of support among Christians and Muslims for democracy. Regardless of their faith, most sub-Saharan Africans say they favor democracy and think it is a good thing that people from other religions are able to practice their faith freely. At the same time, there is substantial backing among Muslims and Christians alike for government based on either the Bible or sharia law, and considerable support among Muslims for the imposition of severe punishments such as stoning people who commit adultery.

These are among the key findings from more than 25,000 face-to-face interviews conducted on behalf of the Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life in more than 60 languages or dialects in 19 sub-Saharan African nations from December 2008 to April 2009. (For additional details, see the survey methodology (PDF).) The countries were selected to span this vast geographical region and to reflect different colonial histories, linguistic backgrounds and religious compositions. In total, the countries surveyed contain three-quarters of the total population of sub-Saharan Africa.

Other Findings

In addition, the 19-nation survey finds:

-

- Africans generally rank unemployment, crime and corruption as bigger problems than religious conflict. However, substantial numbers of people (including nearly six-in-ten Nigerians and Rwandans) say religious conflict is a very big problem in their country.

- The degree of concern about religious conflict varies from country to country but tracks closely with the degree of concern about ethnic conflict in many countries, suggesting that they are often related.

- Many Africans are concerned about religious extremism, including within their own faith. Indeed, many Muslims say they are more concerned about Muslim extremism than about Christian extremism, and Christians in four countries say they are more concerned about Christian extremism than about Muslim extremism.

- Neither Christianity nor Islam is growing significantly in sub-Saharan Africa at the expense of the other; there is virtually no net change in either direction through religious switching.

- At least half of all Christians in every country surveyed expect that Jesus will return to earth in their lifetime, while roughly 30% or more of Muslims expect to live to see the re-establishment of the caliphate, the golden age of Islamic rule.

- People who say violence against civilians in defense of one's religion is rarely or never justified vastly outnumber those who say it is sometimes or often justified. But substantial minorities (20% or more) in many countries say violence against civilians in defense of one's religion is sometimes or often justified.

- In most countries, at least half of Muslims say that women should not have the right to decide whether to wear a veil, saying instead that the decision should be up to society as a whole.

- Circumcision of girls (female genital cutting) is highest in the predominantly Muslim countries of Mali and Djibouti but is more common among Christians than among Muslims in Uganda.

- Majorities in almost every country say that Western music, movies and television have harmed morality in their nation. Yet majorities in most countries also say they personally like Western entertainment.

- In most countries, more than half of Christians believe in the prosperity gospel - that God will grant wealth and good health to people who have enough faith.

- By comparison with people in many other regions of the world, sub-Saharan Africans are much more optimistic that their lives will change for the better.

Adherence to Islam and Christianity

Large majorities in all the countries surveyed say they believe in one God and in heaven and hell, and large numbers of Christians and Muslims alike believe in the literal truth of their scriptures (either the Bible or the Koran). Most people also say they attend worship services at least once a week, pray every day (in the case of Muslims, generally five times a day), fast during the holy periods of Ramadan or Lent, and give religious alms (tithing for Christians, zakat for Muslims; see the glossary of terms for more information about tithing and zakat).

Indeed, sub-Saharan Africa is clearly among the most religious places in the world. In many countries across the continent, roughly nine-in-ten people or more say religion is very important in their lives. By this key measure, even the least religiously inclined nations in the region score higher than the United States, which is among the most religious of the advanced industrial countries.

Persistence of Traditional African Religious Practices

At the same time, many of those who indicate they are deeply committed to the practice of Christianity or Islam also incorporate elements of African traditional religions into their daily lives. For example, in four countries (Tanzania, Mali, Senegal and South Africa) more than half the people surveyed believe that sacrifices to ancestors or spirits can protect them from harm.

Sizable percentages of both Christians and Muslims - a quarter or more in many countries - say they believe in the protective power of juju (charms or amulets). Many people also say they consult traditional religious healers when someone in their household is sick, and sizable minorities in several countries keep sacred objects such as animal skins and skulls in their homes and participate in ceremonies to honor their ancestors. And although relatively few people today identify themselves primarily as followers of a traditional African religion, many people in several countries say they have relatives who identify with these traditional faiths.

Sizable percentages of both Christians and Muslims - a quarter or more in many countries - say they believe in the protective power of juju (charms or amulets). Many people also say they consult traditional religious healers when someone in their household is sick, and sizable minorities in several countries keep sacred objects such as animal skins and skulls in their homes and participate in ceremonies to honor their ancestors. And although relatively few people today identify themselves primarily as followers of a traditional African religion, many people in several countries say they have relatives who identify with these traditional faiths.

| Quick Definition: African Traditional Religions |

Handed down over generations, indigenous African religions have no formal creeds or sacred texts comparable to the Bible or Koran. They find expression, instead, in oral traditions, myths, rituals, festivals, shrines, art and symbols. In the past, Westerners sometimes described them as animism, paganism, ancestor worship or simply superstition, but today scholars acknowledge the existence of sophisticated African traditional religions whose primary role is to provide for human well-being in the present as opposed to offering salvation in a future world.

Because beliefs and practices vary across ethnic groups and regions, some experts perceive a multitude of different traditional religions in Africa. Others point to unifying themes and, thus, prefer to think of a single faith with local differences.