Bonaventure Hotel, Los Angeles

California has been one of the most active battlegrounds in the same-sex marriage debate. The fight began in earnest in 2000, when the state’s voters passed Proposition 22, which defined marriage as the union between a man and a woman. Four years later, following the legalization of gay marriage in Massachusetts, San Francisco began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, a move that was quickly rebuked by the state Supreme Court. And in September 2005, the California Assembly became the first state legislature in the nation to deliberately approve same-sex marriages. Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger ultimately vetoed the bill on the basis of Proposition 22. Now, the California Supreme Court is considering whether Proposition 22 violates the state constitution’s guarantee of equal protection under the law.

The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, the American Constitution Society, the Federalist Society and the USC Annenberg Knight Program convened a distinguished panel of experts to discuss the upcoming state Supreme Court case and other legal issues, as well as the political prospects for same-sex marriage in California and around the nation.

Speakers:

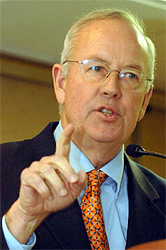

The Honorable Ken Starr, Duane and Kelly Roberts Dean and Professor of Law, Pepperdine University School of Law

Shannon Minter, Legal Director, The National Center for Lesbian Rights

John Eastman, Henry Salvatori Professor of Law & Community Service and Director of The Claremont Institute Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, Chapman University Law School

David Codell, Founding Partner, Law Office of David C. Codell

Moderator:

Dean Reuter, Director of Practice Groups, The Federalist Society

DEAN REUTER: Good afternoon, everyone. My name is Dean Reuter, and I am from the Federalist Society in Washington D.C. It’s my pleasure to welcome you all here today. Thanks for coming. It’s great to see so many folks here in the audience including Judges Waddington, Kazinsky, Smith, Ridgely, and Manny Klausner from the Reason Foundation, and I want to thank also the Libertarian Law Council for helping us to promote this event. They’ve obviously done a great job.

Before we begin, I also want to thank several organizations that have acted as our co-sponsors. In addition to the Federalist Society and its religious liberties practice group and its Los Angeles lawyers chapter, our co-sponsors are the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, the American Constitution Society and the USC Annenberg Knight Chair in Media and Religion. There are several individuals at each of those organizations who have helped put this event together, and I’d like to thank each of them individually, but I fear my remarks would begin to resemble an Academy Awards acceptance speech – (laughter) – and that music would play, and I’d be forced to leave the stage.

Our topic today is gay marriage, or same-sex marriage, or homosexual marriage sometimes with “marriage” in quotes, depending on who you talk to. In my experience, when you’re dealing with an issue on which the folks most intimately involved in it can’t agree on how to name it, you’re in for a lively debate and that’s what we expect today.

This is a topic being discussed nationally and state by state. It’s being litigated here in California, and each of our panelists is involved in some way with that litigation. We are going to focus on the California case and broaden the debate from there.

First, some background on the case for those who might not be familiar with it. It’s a little complex, and I hope I get it right. In 2004, six cases were filed in trial courts. They were coordinated, which I take it is the California term for consolidated, and hearings were held. The trial court held that the relevant part of the California Family Code, which did not allow same-sex couples to marry, violated the California Constitution’s equal protection guarantee. It held that there was no rational basis for that section of the code, and that the code discriminated based on sex, and that it violated a fundamental right to marry without serving a compelling state interest. The state appealed from that decision and the case was then heard in the Court of Appeal, First Appellate District.

In October, 2005, that court reversed and held that there was no violation of the equal protection, due process, privacy or free expression guarantees of the California constitution. A petition for rehearing in that court was denied, and subsequently a petition for review was filed in the California Supreme Court. It was granted and that’s where we are today.

Our format today will be as follows. The four panelists will make initial remarks of about eight to 10 minutes, and then we’re going to have questions from the floor. I’m going to introduce our panelists briefly, in the order they’re going to speak, and then we’ll get started.

Our first speaker is Shannon Price Minter. Shannon is the legal director for the National Center for Lesbian Rights. He’s been involved in cases in California and across the country. Our second speaker is the Honorable Kenneth W. Starr; Judge Starr is dean and professor of law at Pepperdine University School of Law, and he’s also a counsel at Kirkland and Ellis. Our third speaker is David Codell. He is an attorney focused on entertainment, commercial and constitutional litigation, and he’s been involved in several important civil rights cases in his career. Last but not least, we will conclude with Dr. John Eastman. He is a professor of law and associate dean at Chapman Law School. He’s also a director of the Claremont Institute Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence. We’re happy to have every one of them here today, and we look forward to a great debate. With that, if you could start us off, Mr. Minter.

SHANNON PRICE MINTER: Thank you so much. I want to thank the Federalist Society and the American Constitutional Society as well as our host, the Pew Forum, for this truly remarkable opportunity. My colleague, Mr. Codell, and I represent same-sex couples who are seeking the right to marry in a case that is currently before the California Supreme Court; Judge Starr and Professor Eastman have weighed in on the other side of that case. Despite appearances, however, this ultimately is not a partisan issue; it is not an issue about conservative versus liberal views. Some of the most persuasive voices supporting marriage for same-sex couples are those of conservatives such as David Brooks and Andrew Sullivan. Many of the judges who have ruled in favor of same-sex couples have been Republican appointees. And if I can speak personally just for a moment, my parents, who are arch-conservative Texas Republicans – (laughter) – have over time come to embrace full equality for lesbian and gay couples including marriage.

In short this is not an issue that lends itself to simple political or ideological labels. It is ultimately a human issue. The reality, as we know from the most recent federal census, is that more than 100,000 same-sex couples live in California. That’s more than in any other state. Those couples live in every single county in this state, and we know that more than 70,000 children in California have lesbian and gay parents. The question is: How do we deal with this reality? These are real families with real children. How should the law respond?

That’s a question we all collectively have the responsibility to answer. Very often, however, those who oppose marriage for same-sex couples ignore this human reality. We hear many arguments about promoting a certain version of the so-called optimal family and arguments about channeling heterosexual procreation into marriage, but meanwhile, the simple reality is there are hundreds of thousands of same-sex couples, and many of them are raising children. Excluding gay people from marriage will hurt those families, but it won’t cause them to disappear, and it certainly won’t change the fact that these children do have lesbian and gay parents.

In representing these families before the California courts, Mr. Codell and I have argued that the state is constitutionally required to treat these families equally. We believe this is required by the equal protection clause of our state constitution, which prohibits government discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender and any type of government discrimination that lacks a rational basis. It’s also required by the privacy clause of our state constitution that has long been held to protect the right to marry.

Unlike the federal Constitution, the California Constitution expressly identifies privacy as an inalienable right, and the voters in this state amended our state constitution in 1972 for that very purpose. Under our state privacy clause, the California Supreme Court has looked not only to history and tradition, but also to evolving laws and policies, changing social conditions and, generally, our increased appreciation for the importance of protecting human dignity for all people. For these reasons as well as others, we believe that California’s current marriage law violates the California Constitution. More importantly, we hope the California Supreme Court will see it that way as well.

In the meantime, however, there is one point on which all parties in this case agree, and that is the importance of marriage. In 1948, the California Supreme Court became the first in the country to strike down laws that bar interracial marriage, and they held in that case that marriage is a basic civil right. The U.S. Supreme Court has described marriage as a vital personal right, essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness.

Some cultures, of course, arrange marriages and laws that restrict the right to marry based on religion or cast or creed are taken for granted and accepted. In our constitutional system, however, the very essence of the right to marry as the California Supreme Court has held is, “The freedom to join in marriage with the person of one’s choice.” As Judge Kramer explained at the trial court, the court was not saying therefore anyone can marry anyone else, but rather the starting point is one can choose who to marry and that choice cannot be limited by the state unless there is a legitimate governmental reason for doing so. Judge Kramer went on to hold that there is no legitimate reason in this case.

One of the couples in the case, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon, has been together for more than 54 years. They’re now both in their 80s. Because they’re not able to marry, they’re much more vulnerable than their heterosexual counterparts. For one thing, every year they pay significantly more taxes than they would if they were married, and that’s been true now for more than 50 years. When one of them dies, the other will not be eligible for [the] Social Security benefits [of the deceased partner]. If either has to go into a nursing home or long-term care, the other will almost certainly lose their family home, which would not be the case if they were a married couple. The federal Office of General Accounting has identified more than 1,100 rights and benefits that are available only to married people. Despite their five-plus decades of devotion to one another, Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon are not entitled to any of those. While they’re registered as domestic partners in the state of California, the minute they set foot outside of this state, they’ll be treated as legal strangers. Other states don’t have any clear obligation to recognize California domestic partnerships, and most of them have absolutely no idea what that is.

For heterosexual people who are married, it’s very difficult, perhaps impossible, to imagine what it must be like to be barred by law from being able to marry your spouse of 50 years and thus have no way to ensure your relationship with your spouse or your children will be protected, honored or recognized, particularly in moments of illness or other crises. The harms inflicted on lesbian and gay couples by being excluded from marriage are very real, and there is no substitute for marriage. While domestic partnership provides some protection, it falls short of genuine equality by any reasonable measure.

In closing, I want to respond quickly to two arguments we often hear on the other side. The first is that marriage is not just an individual right, but that it also serves important social purposes. Judge Starr is fond of quoting a passage from the conservative philosopher Edmund Burke – it’s also one of my favorites, quite inspiring. Dean Starr has written: “Marriage and family are indeed the quintessential little platoon that Edmund Burke famously celebrated as the first principle of public affections, the first link in a series by which we proceed toward a love of country and to mankind.” It’s a terrible mistake, however, to think the little platoons headed by same-sex couples are any less worthy or capable of achieving those very noble purposes than any other. Society benefits when couples marry and that is true regardless of their sexual orientation.

The second argument we often hear is that studies show children benefit from being raised by married heterosexual parents, and that children are harmed by being raised in alternative families. In fact, however, every single one of these studies has looked at single parent families, divorced families and step-parent families. There is not one study showing children are harmed in any way by having lesbian or gay parents. To the contrary, as Mary Cheney recently stated in response to criticism of her [decision to] have a child with her female partner, every piece of remotely responsible research that’s been done the last 20 years on this issue has shown there’s no difference between children raised by same-sex parents and children raised by opposite-sex parents. What matters is that children are raised in a stable, loving environment. That’s also the position of the American Academy of Pediatrics and literally every single other mainstream child welfare organization.

Justice Scalia has said courts can take no better measure to assure that laws will be just than to require the laws be equal in operation. We’re all here for a very short time. Nothing we do is more important than forging human bonds, creating families and passing on love and, hopefully, wisdom to our children. A person’s sexual orientation is utterly irrelevant to being able to engage in those quintessential human activities. The government should not discriminate on that arbitrary basis, and it certainly shouldn’t use it to deny anyone the freedom to marry.

Thanks. (Applause.)

KENNETH W. STARR: Thank you, and let me join Shannon and David, and I’m sure John as well, in expressing my thanks to the organizers of [this discussion on] this very important topic, and the spirit of reasoned conversation that so characterizes the organizations that have brought us together. My thanks, too, to the judges for leaving their chambers and courtrooms to be with us for this conversation.

This is obviously not just a manifestly important issue, but also, as Shannon has just so eloquently put it, a profoundly human issue. It’s therefore not surprising that people of goodwill are going to come to contrary views on issues of law and constitutionality, and thus we find ourselves in litigation. My happy role is serving as co-counsel to a consortium of very diverse religious organizations, and let me identify them as they are identified in the amicus brief that was filed in the California Court of Appeal at the earlier phase, which is now, as Dean noted, in the California Supreme Court.

Our amicus brief was filed on behalf of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Catholic Conference of Bishops of California, the National Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America and the National Association of Evangelicals. You’ll notice that some of the organizations are national and others are Californian, such as the California Council of Bishops of the Roman Catholic Church.

My points are several. Shannon made a wonderful and powerful statement that this is not a political issue. This is a policy issue, and my fundamental submission today is that the issue should be submitted to “We, the people.” That is not simply a conservative vision, but it’s also increasingly a vision of our colleagues in the academy who would eschew the term “conservative.” I cite to the witness stand as recent examples that distinguished dean of the Stanford Law School, Larry Kramer, who has talked about the importance of popular constitutionalism who’s written eloquently about the need for the people to regain power over the Constitution. Stephen Breyer – I can refer to him as Stephen Breyer in his extrajudicial capacity – in his charming book, Active Liberty, which I commend to one and all, lifts up the vision of the judiciary, articulated brilliantly by Learned Hand, viewed as a judicial conservative, in his 1958 Holmes Lectures at the Harvard Law School, that no matter how brilliant the judges are – and we have brilliant judges here – [they must be] respectful – deeply so – of the democratic process.

Let me also make the point, as a bookmark point, that Learned Hand was not an originalist. It was not his vision that the founding generation had a particular perspective on certain issues including the kind of issues that now arrest our attention; rather it was his view that we live in a representative democracy, and we must take that seriously. We must be extraordinarily deferential to the people in community, and that is what Stephen Breyer has said in Active Liberty. Citing Learned Hand, Justice Breyer said, “We must have important issues resolved by the people themselves. It is, in fact, the very nature of our enterprise to gather to be in conversation together, but it is likewise the practical and prudential way to secure agreement by the people.” Justice Brennan lifted up the vision that that conversation would be robust, uninhibited and open-ended – [see] New York Times v. Sullivan– and two sentences later, Justice Brennan also said that conversation is frequently going to make us uncomfortable.

But what Justice Brennan and others lifted up and what Justice Breyer is lifting up – from the perspective of a centrist, moderate, or however you want to characterize him – is allowing the conversation to go on. Do not stop the conversation by suggesting that the Constitution of California, which is extraordinarily populist in its nature – If there is one overriding theme that we see in the California Constitution, and people here in this audience know it far better than I do, but as an outsider returning to California, looking at the California Constitution, [I find it to be] deeply concerned about the voice of the people. The people will be heard, and they will be heard directly, not through intermediaries and certainly not through relatively unaccountable intermediaries.

This is a vision that should unite virtually everyone of goodwill across ideological lines, and I want to place another bookmark before you. In the Progressive Era, when reform legislation, as it was viewed at the time, was coming forward – I’m going to say that 102 years ago, in his dissent in Lochner which is not admired by everyone in the room and I understand that – (laughter.) I say unabashedly I admire the Holmes dissent because it set forth a very simple view in those five paragraphs – Manny, how many paragraphs? It wasn’t that long. I just asked a non-admirer of the dissent. He said the Constitution was meant for all of us, and it doesn’t yield up answers to the vast majority of economic and social policy issues, but rather provides a framework for democratic conversation.

With respect to this specific issue of same-sex marriage, there are voices – and Dr. Eastman has spoken for these voices of social scientists – who were saying in the spirit of John Adams and Louis Brandeis: “Facts, facts, facts. Please let us study this issue.” Let us, as part of the conversation, understand family structures more, because Dean Reuter made a very interesting comment. He talked about the Family Code. Imagine, if you would, the free speech code. Imagine the free press code. We recoil at the idea of a code, but go to the California Family Code. See how elaborate it is, including who one can marry. What we do know is there are profound limitations on state power, and we should be thankful for those limitations, especially with respect to the idea of invidious discrimination and seizing and hijacking the marriage relationship in order to achieve apartheid-type values.

Now the international conversation is underway, and this is my final point. If a few years ago we’d been talking abut capital punishment for juveniles, we would have been guided by thoughtful people to the experiences of various other countries, and to the fact that very few countries allow the death penalty with respect to juveniles.

Friends, look at the list of countries that have this conversation actively underway, but have not embraced same-sex marriage. Let’s have the social science. Let’s allow the conversation. A very small minority of countries do in fact allow it. And why is that? Because thoughtful people are saying this institution, which has historically been understood to be the union of one man and one woman, is in fact part of our history and part of our tradition, part of our culture and before we change it, before we alter it, shouldn’t we know more in terms of social science, in terms of consequences?

Just to set the stage for the fireworks to come, though I’m sure they will be civil, I leave you provocatively with the very interesting study of the American College of Pediatricians, and the concern set forward by the college with respect to abandoning the institution that has served societies well across the globe.

Thank you. (Applause.)

DAVID CODELL: I’d also like thank each of the sponsoring organizations for inviting me to join you here. My colleague Shannon Minter has already set forth some of the essential arguments we have [presented] in the California litigation. I want to briefly introduce a few federal topics and then discuss the relationship of religion to our topic today.

First, I want to offer a few words about recent efforts to enact the so-called Federal Marriage Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. I think one has to hear the text of the proposed amendment to believe it: “Marriage in the United States shall consist only of the union of a man and a woman. Neither this Constitution nor the constitution of any State shall be construed to require that marriage or the legal incidence thereof be conferred upon any union other than the union of a man and a woman.” Such an amendment would be an utter affront to traditional understandings of state sovereignty and the appropriate balance of federal and state power that is the hallmark of our federal system. The amendment will prohibit states from treating their own residents as married couples.

Moreover, it is conceivable, though not definite, that such language might be construed as prohibiting states through their own republican institutions or direct democracy from choosing to recognize the marriages of couples within their states. By its terms, the proposed amendment would mandate to every state court how it is to interpret its own state constitution and laws.

There is more than a little irony in the proposed amendment’s radical disrespect of state courts. Presumably, some marriage amendment supporters are those who argue in other contexts – such as that of restricting federal court habeas jurisdiction – that the state courts should be afforded substantial respect in the conduct of their judicial proceedings, the interpretation of their state laws and the application of federal constitutional principles. The alarming intrusion into state sovereignty that the Federal Marriage Amendment would represent should be cause for vigilance, not simply by those who favor marriage equality for gays and lesbians, but also by those who believe in limited federal power.

I’ll turn now to a federal measure that did manage to become law by an overwhelming vote of Congress and with the signature of our nation’s first President Clinton. (Laughter.) I’m speaking of course of the so-called Federal Defense of Marriage Act. The Federal DOMA has two provisions: one provision purports to authorize states to ignore the official acts of other states regarding the marriages of same-sex couples. That provision goes so far as to say no state shall be required to give effect to any judicial proceeding of any other state, [or] respect any right arising from a marriage of a same-sex couple.

There is legitimate debate about what the federal Constitution’s Full Faith and Credit Clause requires of the states with respect to recognizing marriages from other jurisdictions. In my view the federal DOMA goes far beyond Congress’s authority under the Full Faith and Credit Clause. That provision begins by stating that the states shall give full faith and credit to each other’s official acts and merely gives Congress power to prescribe how the official acts, recordings and proceedings of the states shall be proved.

But even were it within Congress’s power to enact such a statute, it is unwise for a federal statute to purport to tell the states that they are free to disregard other states’ judicial rulings. A basic reason our federal system works is that the various states credit the official acts of the others. Though each state is sovereign, all the states are interdependent, and their sovereignty depends to a certain extent on each state showing basic respect for the official acts and judicial proceedings of the other states. This is so regardless of whether marriage licenses themselves fall under the Full Faith and Credit Clause. Judgments of state courts certainly do. In addition, it cannot be overemphasized how offensive it is for the federal DOMA to single out same-sex couples who are married for such disfavored treatment under the law.

The second provision of DOMA is a measure that says in federal statutes and regulations the word “marriage” means only a legal union between a man and a woman as husband and wife. The exact meaning of this portion of DOMA is not clear. But I do think it’s clear that it is both unconstitutional and imprudent. First, we should bear in mind that federal statutes have long deferred to the states’ varying definitions of marriage. Federal statutes generally accept the states’ determination that a couple was married as being determinative with respect to federal laws that bestow legal protections on married couples. DOMA is a massive exception.

The federal government, however, has no legitimate reason for refusing to recognize the marriages of same-sex couples in Massachusetts while recognizing heterosexual couples in Massachusetts. Certainly the federal government lacks any legitimate interest in trying to steer gays and lesbians, particularly those who are already in committed same-sex relationships, into heterosexual marriages instead.

The government shows marked disrespect for the institution of marriage by refusing to recognize the valid marriages of same-sex couples in Massachusetts. In addition, DOMA runs afoul of the federal Equal Protection Clause as construed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Romer v. Evans case. There are over 1,100 federal statutory protections associated with marriage. Wholesale disqualification from these protections of same-sex couples who are validly married reaches too broadly and plainly reflects impermissible animus against same-sex couples.

Briefly, I want to address the role of the federal courts and the federal Constitution with respect to which marriages the states may or must recognize. There are two salient principles here. First, as I’ve already mentioned, it is inconsistent with our highest notions of federalism for the federal government to prohibit states from bestowing marital protections on the couples the states wish to deem married.

Second, however, it is fully consistent with our federal system for the Constitution rightly to be regarded as placing restrictions on forms of discrimination in state family law or intrusions in family privacy. Some examples: the U.S. Supreme Court has told the states they are constitutionally prohibited from banning marriages between persons of different races. The U.S. Supreme Court has told the states that the inmates in their prisons must be permitted to marry. The U.S. Supreme Court has also told the states that they must permit married couples to use contraception; that is, to choose not to procreate. In other words, the federal constitution respects the states’ primary role in family law matters while recognizing that there are limits on the states’ powers and that the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses impose particular limits.

Finally, I would like to conclude with some thoughts about the role of religion in the debate regarding marriage equality. As an initial matter, it must be remembered that religion does not speak with one voice on this issue. Though some religions vocally oppose the marriages of same-sex couples, there are many religious bodies in America today that consecrate the marriage of same-sex couples including the United Church of Christ, Reformed Judaism, certain Buddhist communities, the Unitarian Universalist church and many others. To same-sex couples who practice religion within these traditions, the religious sacrament of marriage is as central to their religious and social lives as it is to heterosexual couples whose marriages are recognized by their religions.

For this reason I take exception to the assertion in a recent brief filed by my fellow panelist, Dean Starr, on behalf of certain religious organizations that “religious support for the civil institution of marriage is possible and given without reservation only because the legal definition of marriage corresponds to the definition of most religions.” I also take exception to Dean Starr’s assertion in the same legal brief that “the creation of a gender-neutral definition would fracture the centuries-old consensus as to the meaning of marriage, and in the process spawn deep tensions between civil and religious understanding of that institution.”

The fact of the matter is there is not a religious consensus on the issue of which civil marriages should be recognized, anymore than there is a religious consensus on divorce. This should be irrelevant to the state of California or any other government in this nation, whether most religions believe one thing or another. I suspect there are numerous activities that the Constitution of California protects that may be frowned upon by the religions of the majority.

One of the important lessons of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Lawrence v. Texas is that moral disapproval of a group of people, standing alone, is not sufficient to supply a rational basis for a state law. That is so whether the moral disapproval arises from religion or any other source, as the California Council of Churches recently stated in a “friend of a court” brief here in California, “commitment to religious liberty for all and equal protection under the law means that the state may not rely on the views of particular religious sects as a basis for denying civil marriage licenses to same-gender couples.”

One, nevertheless, frequently hears the objection that the state should not recognize marriages of same-sex couples because it would somehow infringe on the free exercise of religion by those whose religions disfavor same-sex relationships. The argument apparently is that even in civil life, religious people should be exempt from treating same-sex couples as married. That complaint has no validity under the law.

A few examples make plain why that is a good thing: religious objection to interracial marriages was strong just decades ago and may still be strong in some circles. In addition, some religions might find heterosexual divorce as objectionable as the marriage of a same-sex couple, but California’s laws neutrally prohibiting discrimination based on marital status apply, appropriately, across the board. If same-sex couples are permitted to marry, the First Amendment will protect every religion’s right to decide for itself whether to consecrate such marriages, but the freedom of religion protected by the First Amendment is not infringed by civil recognition of families that fall outside what some religions regard to be the ideal form of family.

In closing, I’d simply like to say that far from posing any threat to the institution of marriage, same-sex couples who are seeking the right to marry wish to partake fully in that institution and indeed to bolster it. There is no need to defend marriage against such families and their children, but there is every reason to welcome those families into marriage.

Thank you. (Applause.)

JOHN EASTMAN: It’s the first time I’ve ever been accused of writing a Brandeis Brief. (Laughs.) But I guess we did in a bit [sic].

Let me take the issue with a couple of points David made. And just for clarification, the Federal Marriage Amendment, when it says no state court shall construe or no state constitution shall be construed to require same-sex marriage, that doesn’t limit the legislatures of the states from adopting same-sex marriage if they choose. That amendment is designed to foster what Judge Starr, or Dean Starr, was talking about, that we’re going to reach this policy issue through a deliberative and collaborative process, engaging one with another to look at the implications. We don’t want the courts deciding it for us as a matter of construing state constitutional clauses that were never addressed to this particular issue.

I have a slightly different take on the Lochner point Dean Starr made because I do agree there are some issues where you cannot simply leave it to the deliberative democratic process. We do have constitutional protections against majority tyranny. You want to make sure that majorities through this deliberative process can’t trample fundamental rights, can’t seek out discreet and insular minorities – Carolene Products footnote four is full of this idea that there are protections for individual rights that the courts are supposed to be there to address even against willful majorities. The issue for us is, is this is one of those kind of rights?

I would still disagree with the Supreme Court’s opinion in Lawrence or the Massachusetts decision in Goodridge. If he’d had said this is a discrete and insular minority and subjected it to strict scrutiny or had said this is a fundamental right and therefore subject to strict scrutiny – but neither of those courts did that in either the context of homosexual sodomy in the Lawrence case or gay marriage in the Goodridge case. Instead, both purported to apply rational basis review, the lowest level of scrutiny that the courts give to legislative judgments. All I have to do to meet rational basis review is to show there’s a legitimate government purpose and that the restriction is reasonably tied to that purpose. I don’t even have to be right about that. It’s actually even more removed than that. Could the legislature reasonably have thought that its restriction might further that legitimate governmental purpose? Of course, the answer to that in both contexts is yes.

There’s an extraordinary line in Justice Marshall’s opinion in Goodridge that I think highlights this point better than anything else. She could conceive of no rational basis for a marriage law that distinguishes between heterosexual and homosexual couples even with respect to the procreation and rearing of children. Now, that’s really astounding. The equal protection clause at its core is to guarantee equal treatment for equal things, not equal treatment for unequal things or unequal treatment for equal things.

The relative question here for us is: With respect to the procreation of children, are there any differences between heterosexual and homosexual couples that the law can recognize? To say that there are not is to invoke disbelief; it’s actually a dishonest opinion. I would have much greater respect for it if it had said, “This is strict scrutiny. This is a discrete and insular minority that, because of historical traditions, because of majoritarian views, cannot ever prevail in the democratic political process” that Judge Starr set out. But that’s not what those opinions did. It’s that concern about the improper utilization of the judiciary to create a massive policy shift in this country without deliberation on the possible ramifications [that is troubling.]

I was at a conference a year and half ago at Brigham Young where another staunch advocate of gay marriage began by saying, “What difference does it make to your heterosexual marriage if I enter into a homosexual marriage?” This kind of libertarian focus on individual rights as the norm of marriage, the model that we should support – well, we all understand what difference it makes because marriage has never been understood in this country as simply a matter of fundamental individual right. The reason we have marriage laws as a foundation of society is that as members of the society, we all draw benefits from that institution, in procreation and rearing of children by the two people in the universe who are most adapt at making sure that job gets done right: the natural parents. That can only exist most readily in a heterosexual marriage by the natural parents.

The studies that David and Shannon pointed to earlier that say children do better in heterosexual couples [composed of] their natural parents; that model doesn’t work in any other context. It’s not just stepmother and stepfather, it’s not just adoptive parents, it’s anytime there are anything other than the two natural parents. There’s one exception to that, one very close to that is a single mom – not a single mom who had children out of wedlock and the father was never part of that – but a single mom whose [husband] died after the kids were born. That father remained an inspiring omnipresence in the home. “What would your father think if he were still here?” Those children end up pretty close to the par of the heterosexual norm.

They are right. The social science we have on gay couples is relatively in its infancy. There are some early studies out that, quite frankly, are politically driven, methodologically flawed and have been pretty solidly rebutted. But there is no serious study that comes out one way or another on that question, and therefore it’s an open question, whether there’s something about this particular relationship that might mirror the one history has told us is the norm through all these times. What are the consequences if we get this wrong, and why is it so important to listen? We’re living through the consequences of the similar, largely judicially imposed decision of a generation or two ago.

This professor I mentioned at the BYU conference talked about how important marriage is and how we have fundamentally changed it in our history. What he was talking about was the advent of the no-fault divorce rules in the 1960s and early 1970s, initially driven by court decisions, subsequently then adopted by legislatures. It’s hard to pinpoint in the social science exactly what the consequences of those [decisions] were, but the consequences to our society are pretty severe. The number of out-of-wedlock births, the number of children in prison or youth facilities, the teenage suicide rates, all of these things have skyrocketed – skyrocketed – since those decisions in the 1960s.

Has any study proved a direct correlation between those two yet? No. But I think we’d be foolish to think there is not some connection between that undermining of the fundamental institution of marriage that for millennia has served as the transmission of cultural norms, making those things difficult, and the loosening of those bonds and seeing those things flourish. It’s that undermining of marriage we’re talking about. This is not just the people who support the old model. What we’re talking about here is a fundamental transformation in the notion of marriage, a complete severing of the marriage idea from that old connection to procreation and the rearing of children. We’re making it an institution across the board that now means something radically different than it has ever meant before.

Now, that many not have any consequences for us as a society, but I think the no-fault divorce model demonstrates to us that in fact the consequences may be huge and profound, and we as a society absolutely must engage in a debate before we take this step. I don’t know where we’ll end up at the end of that debate. We may well end up one place and realize 50 years from now we made a grievous mistake on either side, but it is a policy debate, as Judge Starr pointed out, that absolutely requires us to utilize the democratic institutions, not the aristocratic institutions, of our government.

Let me close as [with words from] Abraham Lincoln as he dealt with an issue similar to this: whether we were going to have the courts take us out of a policy debate in response to Dred Scott. He said, “The candid citizen must confess that if the policy of the government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the people have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.” That’s what we’re opposed to here. We need to have this debate civilly on policy grounds before we make one of the most radical changes in one of the most basic foundation blocks of our society.

Thank you. (Applause.)

REUTER: Thank you one and all. We’re to that point in the program where we can take questions from the floor. Let me start off.

One of the themes that seemed to run through several of the presentations was the question of who decides this issue? At least three of our speakers talked about that and then John you went on to talk about the tyranny of the majority, I guess alluding to John Stewart Mill and Tocqueville, and also tying in the ideas of fundamental rights. I take it from your discussion that if there’s a fundamental right involved, then the courts can trump the majority. The question then is who decides who decides? When is there a fundamental right identified, and how do we get to that point? I’ll address that to you, Professor Eastman, or anyone else on the panel.

EASTMAN: It’s a great question, and it’s one that divides the two staunchest conservatives on the court, Justice Scalia and Justice Thomas. Justice Scalia would look only to define that by our history and traditions, and the short answer for him would be homosexual marriage was never part of our history and traditions, therefore it’s not a fundamental right, therefore there’s not an issue. I think Thomas’ position would reach the same conclusion, but by a much different path. He would look to the two sources of how we define fundamental rights, the same sources I think Jefferson looked to when he penned the Declaration of Independence. We set out propositions grounded in nature and nature’s God. That’s revealed religion and [the] morality that flows from it – the same kind of moral principles that flow from our rational thinking.

Nature and nature’s God, reason and revelation. Those two components have both been rejected by the courts in this discussion. The briefs filed in the Lawrence case and the opinions in the Lawrence case reject any notion that we can have a moral view about this that guides what defines fundamental rights, even though it has been defined that way for centuries, but also rejects the notion of reason. Saying that we cannot distinguish between heterosexual and homosexual couples even with respect to the rearing of children is a proposition that simply ignores basic rational thought.

CODELL: On the question of who decides, we all agree that if there’s a constitutional provision violated by a statute, then we have to review both under the federal Constitution and under the state constitution here in California. In the marriage litigation in California we are challenging the marriage statute’s exclusion of same-sex couples on equal protection grounds, privacy grounds and on a fundamental-right-to marry grounds, as well as some free expression grounds.

In California, the identification of a fundamental right to privacy in our state constitution is, as Shannon Minter’s already explained, not based simply on the history of our state, and what has always been understood to be a fundamental right, but instead takes into account changing social conditions, the real world that we live in. It’s simply not the case under the California Constitution that we are frozen in time at the enactment of the constitution.

With respect to the equal protection clause, we have powerful arguments that the marriage exclusion here in California discriminates based on sexual orientation and discriminates based on sex and so therefore [should] be subject to heightened scrutiny by the California courts. These laws cannot stand simply because there might be some rational basis for them. Rather the state must show a compelling reason and show that these laws are narrowly tailored to meet that compelling reason.

That said, even under state law in California there has been no rational basis set forth for this law that can survive even the lowest level of rational basis review. The California Supreme Court does not blindly defer to the legislature. Rational review in California has some bite. You can’t simply rely on, for example, moral disapproval of a group. In fact, the U.S. Supreme Court has made clear that’s impermissible in Lawrence v. Texas. So there are powerful arguments [as to] why the courts do have a role to play here.

That said, obviously any measure that has popular support when it goes into effect is preferable to a measure that the public may not want, but that point only goes so far. We have to remember that the ultimate expression of the public will in the state of California is the California Constitution, with its privacy guarantee and due process guarantee. Those are expressions of public will. The courts do not impose anything on the people by accurately interpreting those provisions and declaring what those provisions mean even if it means striking down a statue that has wide popular support.

MINTER: Can I very briefly tack on to that? There’s a frustrating circularity here, because everyone agrees that if there is a serious constitutional violation presented by excluding same-sex couples from marriage that it’s appropriate for the court to step in and resolve that. The disagreement really comes down to whether there is a serious constitutional violation or not. As David just set forth here, our view is that there is. I’ll relay a helpful comment I heard Chief Justice Ronald George of the California Supreme Court make recently in a public forum, that the best definition he’s heard of a judicial activist is a judge issuing a decision that one doesn’t like. I think there’s a lot of wisdom in that.

I also wanted to relate it to the Dred Scott point because we’ve heard a lot lately from certain conservative quarters trying to link critiques of substantive due process to the Dred Scott decision. I wanted to share what I think is a very persuasive passage from Justice Janice Brown, who’s no longer on the California Supreme Court. She addressed this in a case a few years ago; she noted that “the true vice of Dred Scott lies not so much in the fact that it treated prohibition of slavery as nothing less than an assault on the concept of property” – substantive due process concept – “but rather [that] a majority of the United States Supreme Court endorsed the then-prevailing societal view that African-Americans had no rights the white man was bound to respect.”

The true lesson of Dred Scott is we should be very cautious about assuming that another group of people doesn’t fully share basic human attributes such as the ability to procreate and raise children. Frankly it’s painful to hear the suggestion that it should be shocking that anyone would suggest that same-sex couples and heterosexual couples are similarly situated in that respect. Obviously we believe they are, and the California legislature also has gone on record as firmly believing in standing for the proposition that same-sex couples exist in this state and that their families ought to have equal protection.

STARR: May I briefly comment? I would simply cite the Supreme Court’s decisions 10 years ago in the end-of-life cases coming out of Washington and New York. The courts, through different interpretative methodologies embedded and embodied in the various opinions, came to the unanimous view that the Constitution simply did not yield up an answer with respect to the state’s interference with the determination to end one’s life. Talk about a fundamental liberty interest: [that case involves] pain and suffering and perhaps great expense to the family. The powerful moral case can be made, and it’s been successfully made in various countries around the world. It’s certainly been made successfully in Oregon, and it continues to be a very lively issue here in California.

But [in] the Supreme Court – and it’s essentially the same Supreme Court ideologically – the moderates and those who some might view as to the left of the moderates were all of one accord, that the Constitution should protect the marketplace of ideas so we can debate these policy issues. Of course, you have a fundamental interest in the state not laying its hands upon your body, but the state does have a profound interest in life and the sanctity of life. The courts simply said at the end of the day – when one reads Washington v. Glucksburg, again very different interpretative methodologies, but all nine justices of the court then sitting said, “Allow the democratic conversation to go on.” They were foreshadowing Justice Breyer’s vision of the active liberty of the conversation.

Now, this is more in the nature of a rebuttal. It is very valuable that we lift up, as our colleagues on the other side of the issue have, the values of federalism. This is a very good thing, concerns about DOMA and so forth treading on federalism values.

But federalism of course is simply another structural principle in favor of self government, and surely the idea that states should be able to experiment does in fact mean that Oregon should be able to go its own way, and Washington State or California or Nevada should be able to go their own ways. But the fundamental issue that I think both John and I would leave before everyone is the Constitution simply does not yield up an answer to this particular question, and that’s what our very able colleagues are very skillfully arguing to the California Supreme Court. Yes, the answer has been there all along.

Final point, the Defense of Marriage Act can be criticized on policy grounds – we’ve heard that [here] – it can criticized on constitutional grounds – the Full Faith and Credit Act – but surely that goes to the final point that was just made by John, with respect to rationality. The Congress of the United States overwhelmingly enacted the Defense of Marriage Act, section 2 of which defines marriage in the traditional way, and it was signed in the law by President William Jefferson Clinton.

REUTER: Let’s go to questions from the floor. I will give you the opportunity to identify yourself and your affiliation if you want, and we’ll start over here with Manny Klausner.

KLAUSNER: Thank you. I’m chairman of the Libertarian Law Council and the founder of the Reason Foundation. John alluded to one of his opponents at BYU giving a libertarian view on the subject, and I would say that as a libertarian it’s clear that on the policy issues, libertarians are divided. Minter said that, as I understood his remarks, civil unions don’t go far enough. I’d like to hear some elucidation from any of the panelists as to why civil unions are not a sufficient approach in terms of the policy debate.

MINTER: They don’t offer in a purely practical sense anything approaching actual equality. Civil unions don’t give same-sex couples the ability to seek any of the more than 1,100 federal rights and protections that are tied to marriage. Civil unions don’t have the kind of portability we associate with marriage. Especially nowadays when people travel and move often, it leaves people in a very vulnerable condition. Perhaps more fundamentally, there simply isn’t a rational basis to try and create out of whole cloth a new separate legal status for same-sex couples simply because they’re same-sex couples.

If we look at why marriage is a protected right – The way the California Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court has approached the question, of how to determine whether a particular claimant has a right to participate in a right that’s previously been established as fundamental – You look at the attributes of that established right and then you ask the question, “Is there something about this particular group of people that disqualifies them from being able to participate and benefit from those attributes?” When it comes to marriage, [the answer is] no. We know from a number of cases, most importantly Turner v. Safley the U.S. Supreme Court has told us what they think are the essential attributes of marriage that entitle it to be protected as a constitutional right. That has to do with an expression of commitment between two people, an acknowledgement that marriage has a spiritual significance for a lot of people and an acknowledgement that marriage is the gateway to a number of protections and benefits.

There’s just nothing about gay and lesbian people or being in a same-sex relationship that disqualifies anyone from being able to participate in and benefit from all of those attributes. We think at the end of the day it is irrational and invidious to try to create out of whole cloth a whole new separate legal status for lesbian and gay people solely in order to maintain a distinction between gay and straight people. That’s not the way our constitutional system is supposed to work.

CODELL: Could I just add that when the state of California sets up two systems of family law, marriage and domestic partnership, and says to gay couples, “you go over here” and says to heterosexual couples, “you go over here,” the state of California is saying to our friends, our neighbors, our family, our government actors, that sexual orientation is a valid basis for distinguishing between people and for distinguishing between families. In fact, sexual orientation is not a valid basis for distinguishing between families or people, and it’s actually contrary to California public policy as it has been developed by the California legislature over the last 10 years and as the courts have recognized. It is a form of invidious discrimination for the state to divide families based on a characteristic, sexual orientation, that plays no role in one’s ability to contribute to society and have strong, lasting family relationships.

WILLIAM BECKER: I’m proud to be co-council with Manny Klausner and John Eastman on a religious liberties case. My question’s for the conservative side. I wonder if you could deliver your oral argument on the equal protection argument, which I really haven’t heard from the conservatives yet, and also contrast that with the slippery slope argument.

STARR: I think John did. I heard him discuss the rational basis test. The traditional form of marriage has been embedded in our laws for literally millennia and has been ratified by the people because of concerns about the integrity of the family unit and the welfare of children. One may disagree with that, but the family codes are quite elaborate with respect to the responsibilities of spouses, one to another, and to the rearing of children and certain assumptions that flow with respect to whose child this is. This very elaborate body of law is all built upon a single edifice and that is the traditional definition of marriage. That certainly goes, it seems to me, to the rational basis that this is a traditional institution since time out of mind that has been viewed in one particular way, with the welfare of children very much in mind.

It doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have a discussion about whether children are equally or better protected in other kinds of relationships. The conversation obviously remains open. You just heard the argument that with respect to strict scrutiny, the courts simply have not been willing in any of the cases to say that sexual orientation is in fact a grounds for triggering strict scrutiny. Why is that? This has been part of the dialogue as well; various statutes, including federal civil rights laws do not reach so far. And why is that? Because there’s a history and a tradition. That history and tradition may change, but it’s difficult then to advance the view that this is a fundamental liberty interest in light of the history and tradition that informs this elaborate body of law.

EASTMAN: Let me add to that. Social science literature, just on the heterosexual side, shows, at a statistically significant level, that the children of two natural parents end up having fewer problems than the children of one natural parent and another step father or step mother. Therefore, under traditional rational basis review, it seems to me perfectly rational and legitimate for a legislature to say that the two natural parent phenomenon has something to do with the most effective rearing of children that we’ve seen in human history. It’s not irrational to think that, therefore, if I get into a relationship that by definition does not have two natural parents rearing that child that those children may be at a disadvantage. That’s not irrational under our traditional rational basis review.

The reason the courts don’t want to take it to strict scrutiny and define this as a fundamental right – Think about what flows if you define either sexual orientation as a suspect class: why limit it to two homosexual persons? Sexual orientation has lots of variations. If it’s a suspect class, all of those variations also get strict scrutiny. If you instead look at fundamental rights as the way to get to strict scrutiny – Fundamental right to marry has never been the definition for fundamental right; it’s been the fundamental right to marry as we’ve defined marriage.

As I start treating it more broadly than that, as a broader fundamental right to marry whomever I wish, then all of the laws on incest, adult consensual – let’s take other things off the table – fall by the [wayside] because they’re intrusions on fundamental rights that arguably don’t meet compelling interest with, that are narrowly tailored. The laws against plural marriages all fall because they don’t meet that same standard as well. I think it’s that reason Justice Kennedy claimed to be applying only rational basis review in Lawrence, while Justice Marshall in the Massachusetts Goodridge decision absolutely refused to take this to strict scrutiny. The ramifications of that decision are profound, but to pretend that this doesn’t meet our traditional notions of rational basis review is just dishonest.

JEFF JACOBBERGER: First, a comment. I was raised as a Christian and read all about polygamy in the Old Testament, and my last boyfriend was a Mormon, so I know something about – (laughter) – the Latter-day Saints. For you to state that for millennia we’ve understood marriage to be between one man and one woman is simply a historical lie. Actually, I appreciate your comments, Judge Starr, about representative democracy. In the state of California we had a political process that started with the very weak domestic partnership law [and] has gradually been strengthened. We got a marriage law through the General Assembly and off to the legislature, though vetoed by the governor. Perhaps California might be a place where the political process is working.

My question for you, on the conservative side of the issue, is with respect to the Federal Marriage Amendment, where there is an attempt to lock in what you hope is two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of the states in favor of the amendment – is it an effort to keep the political process from working? Because it means that those who favor gay marriage have to wait until we get two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of the states. I’d like your response to that comment.

STARR: Yes. I’m not in favor of a constitutional amendment. I tend to disfavor adjusting the Constitution, even for strongly held reasons, so I for one don’t embrace it. One of the reasons I don’t is that marriage and family issues have historically been entrusted to the states, and for pro-federalism reasons I get worried when the federal government sees fit to intrude – and I see it as an intrusion – into this traditional arena of state authority. On that I think there’s a likely to be a fair amount of agreement among all of the panelists and certainly a lot of people with whom I’ve chatted who feel strongly that this is a matter for democratic debate and resolution.

You rightly point out that the democratic conversation in California has moved very far along, including the passage through the General Assembly and the governor’s veto. One of the intriguing and, I suppose, ironic dimensions is that the issue is in the courts. (Laughter.) It shouldn’t be in the courts, in my view, it should be in Sacramento in the Assembly halls. Let’s allow the Assembly to work its will and the governor to face this issue on its merits. I am very sensitive to federalism values and the ability of the various states, including if California goes that way, to go the way the people of that state feel through the democratic conversation it should go.

EASTMAN: Let me take the other view, [and play] the devil’s advocate on this. One of the problems with the state-by-state experimenting model is that it’s not limited to a single state. Couples from 46 different states secured marriage licenses in Massachusetts shortly after the Goodridge decision. They didn’t stay in Massachusetts. They went back to their states, and there’s a panoply of litigations over will the state recognize our divorce if we split up when they didn’t recognize the marriage? What are the intestate succession rules that apply?

Massachusetts’ decision or California’s decision is going to have profound impacts in other states as people move there. It’s that challenge to the public policy decisions of those states that is undermined and is part of the driving force behind the Federal Marriage Amendment. The nature of the question becomes such that you cannot have it state by state. I think that’s part of what’s driving the people: the transportability of the California judgment. Imposing it on Tennessee, when the people of Tennessee might have had a counter judgment, that is driving part of the Federal Marriage Amendment discussion.

CODELL: Family law has varied dramatically among the states for the entire history of our nation; divorce laws used to be radically different; there were differences in adoption laws. The states have worked it out, the state courts have worked it out, the state legislatures have worked it out. There is no reason to enact a federal amendment saying that no state in this country can permit same-sex couples that live within those states from marrying. Furthermore, when a same-sex couple that lives in Mississippi marries in California and goes back to Mississippi, I’d be hard pressed to understand what kind of public policy in the state of Mississippi is really being damaged by that marriage, but I’m sure we’re going to disagree on that.

STARR: Just one footnote, and this is definitely three cheers for federalism. A number of states are in conversation with respect to different tiers called the multi-tiered marriages, covenant marriages. It began in Louisiana and was quickly adopted in Arizona and Arkansas and is now under considerations some 29 [states] – it’s a very interesting idea. Stronger entry requirements, stronger exit requirements. New York State has a very rich history of essentially delegating the question of certain marriage issues to rabbinical courts – some interesting constitutional establishment clause issues there. But through the democratic process the state – and this is true in most nations – does not seize monopolistic authority over the definition of marriage, but rather allows religious communities and other communities to speak to this issue. One thing we have not talked about at all is should we encourage the federalism experiments, the laboratory of the states, so we can experiment with the idea of multi-tiered marriages?

UNIDENTIFIED QUESTIONER: There’s been discussion of popular sovereignty, and I remember living through the Proposition 22 debates. We debated all this and the people spoke, and yet you say that popular sovereignty is not to be respected, and you challenge it in court. I wonder if the people at that time had done it right and made a constitutional amendment out of it, if you’d still be here, because I think you’re litigating constitutional amendments that were passed by other states, some 15 states now that have constitutional amendments prescribing marriages [as] the marriage of a man and a woman. You’re involving litigation there, which to me demonstrates a certain disingenuousness about this reference to popular sovereignty.

CODELL: I’m not sure there is any state litigation in states with constitutional amendments. I don’t believe there are any federal cases –

MINTER: There was the case arising out of the Nebraska amendment that has now been resolved. The Eighth Circuit rejected the challenge to the constitutionality of Nebraska’s constitutional amendment.

REUTER: Lets ask the question this way: If Proposition 22 were a constitutional amendment, would you be here today behind this case? I think that’s the gist of the question, isn’t it?

STARR: Of course you would. (Laughter.)

CODELL: Would we be in state court, purely on state constitutional grounds if there were a constitutional amendment banning it? I think it would depend on how broadly that proposition purported to go. Any kind of proposition that would try to seal out gay and lesbian couples from state protections across the board would be subject to challenge. If the measure were simply applied to marriage as a constitutional amendment, you’d have a hard time winning in the state courts on state constitutional grounds.

REUTER: Let me ask the question on this side. If things come out differently in the political process, are you going to be as sanguine about who decides?

STARR: I am. I think John has expressed concerns. (Laughter.) I’m willing to allow the conversation to unfold in the various states, and what happens happens. It’s one of the reasons I was quite distressed to see the Justice Department attack Oregon’s medical marijuana law. I felt that was a very poor use – (applause) – of judgment and a very poor interpretation. I realized some very respected justices completely disagree with me, and so I may very well be in error, but that’s the pro-federalism in a lot of us that says, “We’re willing to live with the results of the democratic conversation, but our plea is to allow that conversation to unfold.” You will end up having a much happier and healthier polity if you do it that way. So this is a plea, a cry of the heart, that we’re doing that in the end-of-life issues, we’re having that kind of conversation, but look at the rancor and acrimony that is for ever with us because of Roe v. Wade.

EASTMAN: I take the same position. I try to draw that distinction in the no-fault divorce case: I criticize those states that did that by judicial fiat, and I thought they were foolish, but defended their right to be foolish. Similarly, in the brief we filed in the Supreme Court’s medical marijuana case, I defended the ability of California to make a foolish decision. It’s not a part of the federal Commerce Clause authority. One of the things you have to recognize when you allow things to be subjected to the deliberative process in a democracy is sometimes the majority gets it wrong, but then the majority has to suffer the consequences of its own mistake, and it is also in a position to correct its mistake. When it’s imposed upon you by a court, no majority can correct that mistake and that’s the problem of doing this by judicial fiat.

CODELL: Except that we have the courts to correct mistakes. That’s part of the reason we have judicial reviews, so if the people make a mistake, the courts can correct it.

TERRY STEVENSON: I just want to thank all of you for this wonderful program. I agree with Professor Eastman that the courts are extremely disingenuous using the rational basis test when strict scrutiny should be the test. But in California under the Fair Employment and Housing Act sexual orientation is a suspect classification. Hasn’t the horse already left the barn on that one in California?

EASTMAN: The fact that it’s a suspect classification by virtue of statute does not override the other statutory provisions, including Proposition 22, which don’t treat it as such. If you were to have that suspect classification imposed as a constitutional matter, then I would agree.

CODELL: The Legislature made quite clear that the public policy of the state of California is that discrimination based on sexual orientation is improper by any branch of the government or any program that receives government funds. The Legislature has spoken clearly about what the state’s public policy is. If you apply the factors that the California Supreme Court has announced for what constitutes a suspect classification, including a history of discrimination, including irrelevance to one’s ability to contribute to society, then I think sexual orientation easily falls within the categories that the courts have to subject to heightened scrutiny. That means that the courts should presume that any law that discriminates based on sexual orientation is invalid because what valid basis is there for discriminating against people based on their sexual orientation? The Legislature has said none, and it said that with respect to almost every aspect of public life. I think the Legislature has it right, and I look forward to the day the California Supreme Court agrees.

STARR: But, with all respect, the Legislature has not said it with respect to the issue that brings us together. There is a huge transportation issue of bringing that determination with respect to one set of issues, such as housing and housing discrimination, and saying, “Here is that same principle with respect to the definition of marriage.” I don’t think fairness has been given in terms of our treatment of the California Court of Appeals, the Intermediate Court’s decision in this case, and I do commend the two opinions, [including] the very impassioned, very powerful dissenting opinion. But I want to lift up the majority’s opinion in this context, since it goes to the specific question: the majority’s opinion looked very carefully and, I think, quite respectfully to the conversation that has been underway in the General Assembly and elsewhere, seeing the march in favor of sensitivity and protection of gay and lesbian individual liberty interests and their interest in having particular kinds of protected relationships.

Our colleagues on the other sides say that’s not enough. Manny Klausner asked the question of why is that not enough. But the point that was before and persuaded a majority of the justices on the California Intermediate Court of Appeal is that one needs to look holistically at not simply the history and tradition but also at the entire march of what the legislature has done. What the legislature had come up with at this time and place in our history is essentially a balanced approach that easily passes the rational basis test.

EASTMAN: I don’t think you can look only at the subordinate legislative authority in this state, the Legislature. The ultimate legislative authority in this state, the people, actually had the legislative pronouncement about this as well and that prevails over the subordinate legislative judgments. Proposition 22 is the law of the land – unless it violates directly a provision of the state constitution, [which] they’re arguing that it does. But they have to concede that it violates those provisions only by giving them an interpretation that has never existed in our history before.

UNIDENTIFIED QUESTIONER: My question goes to the question of rational basis. We heard, Dr. Eastman, that you looked at the social science behind raising children as a [possible] rational basis for treating lesbian and gay people who want to marry differently from heterosexual people. But given that, as has been described, lesbian and gay people live in committed relationships, do have children and are raising them and that there are civil unions that are recognized by the state – and that the state recognizes the marriages of people who are step parenting and the other non-socially science validated ways of raising children. Given that those things are both the case, is there any other reason then, besides the sexual orientation of the people, that would create such rational basis? Isn’t that the argument for why leaving the discussion open to the majority when it’s just the difference between the two sexual orientations – Is there a rational basis or is there a harm to marriage from just that?

ALLISON MILLER: I am the president of the new Pepperdine Chapter of the American Constitution Society. Dean Starr, you had discussed the democratic discourse leading to a “happier” policy. I think I understand what you meant by that, but my question for you is, how do you address that in terms of Massachusetts, where, I believe, public sentiment towards gay marriage actually increased after they allowed gay marriage not by the democratic process.

The second question relates to children. Given the number of children being raised in gay and lesbian relationships, what would your comments, Professor Eastman, be about protecting that family and those children while still arguing that it would not be a protection of the family and the children to allow gay marriage?

DIANE GOODMAN: I’m president of the Academy of California Adoption Lawyers. Judge Starr, you talked a lot about the Family Code and its provisions relating to the conduct [in] the heterosexual family unit. But the Uniform Parentage Act, which is in the Family Code, talks specifically about finding other types of parents. The California Supreme Court in at least four decisions in the last few years has ruled that you can have two parents of the same gender or two different-gender parents who aren’t married. Why is the issue of parentage even relevant to the discussion of who should be allowed to be married?

MICHAEL TANENBAUM: I’m a lawyer here in California and a law professor in Europe. I have an empirical question, and I guess it goes more to the gay marriage advocates. I heard it said a couple of times that there are 1,100 benefits to marriage under the law. I’m a single guy, not yet married yet. I didn’t know it was such a good deal. (Laughter.) I’m wondering if you could help me understand what some of those us are, or how I get a catalogues of those, and also which of those are unavailable to people who would otherwise just arrange their affairs by private contract?

STARR: Let me just say to my wonderful Pepperdine colleague – and I call my students colleagues because we’re studying all this together – that, yes, I think it is happier. What I mean by that term is it’s healthier in a democratic society, regardless of the opinion polls, which may wax and may wane. I just cited, again, the nation’s excruciating and continuing experience with the abortion controversy, and the sad and poignant call by the plurality in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, now 15 years ago, to stop the debate. The court has spoken, so there are certain issues that the court should just take off the table, and we’ve now taken abortion off the table.

[But] no, they haven’t. They haven’t even taken it off the table with the Congress of the United States, with duly elected presidents of the United States. Especially for the students here who have grown up in a culture that looks to the courts for succor or constitutional interpretation, Marbury v. Madison and so forth, I would say take a page again from Holmes and the tradition Holmes began articulating, [which was then] carried on through Brandeis, through Cardozo, through John Harlan the second – Harlan the first as well – Frankfurter, Byron White, Learned Hand, Henry Friendly, I could go on. These are numerous judges, appointed by presidents of different parties, who have lifted up the vision that we have a fundamental right in this country and that’s the right to govern ourselves.Of course there are limits, and Dr. Eastman rightly pointed to those limits. But let’s have that discussion, let’s have that debate and if the polls in Massachusetts are running in favor of same-sex marriage, that’s fine but look what happened: by virtue of the Goodridge decision, many states rose up in righteous indignation and amended their constitutions. I have heard some pundits from the Democratic Party [say] that if it weren’t for Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Goodridge, John Kerry would have been elected. It was that serious a political issue. Many people went to the polls in 2000 feeling very strongly – rightly or wrongly – about this issue. Why? They wanted to be heard, and they insisted on being heard.

EASTMAN: Let me take up the 1,100 [benefits]. I know a lot of people in marriages who will say on some days, every one of those 1,100 benefits is barely enough. (Laughter.) Let me take up the serious question. The Uniform Parentage Act is the way I’ll tee off the two questions. The fact that California policy has recognized that it’s better for kids to be reared in any committed relationship, rather than being raised in a foster home or in an orphanage, is a compassionate response to a serious problem we have in this country. That doesn’t mean that as a matter of policy California has said there is no difference between any of those secondary options or backup options and the primary option that Proposition 22 recognizes.