The personal identities of Black Americans are tied to many different characteristics, some of which are more important than others in shaping how they see themselves. In the new Pew Research Center survey, Black adults were asked about the importance of their racial background, ancestry, the place where they grew up, gender and sexuality to how they think about themselves. In addition to personal identity, the survey explored Black Americans’ views of how much they have in common with Black people who are U.S. born, immigrants, wealthy, poor and LGBTQ. It also asked Black Americans about how much what happens to Black people locally, nationally and globally affects what happens in their own lives.

The importance of race, ancestry and place to personal identity

Race and personal identity

The majority of Black Americans identify as Black alone and non-Hispanic. However, 8% of Black adults identify as multiracial, that is Black and some other race, and 5% as Black Hispanic. Between 2000 and 2019, the share of Black Americans who identified as either multiracial or Black Hispanic had grown by roughly 145%. To capture this growing complexity in Black racial identity, Black adults were asked both a general question about the importance of their racial background and a more specific question about the importance of being Black.

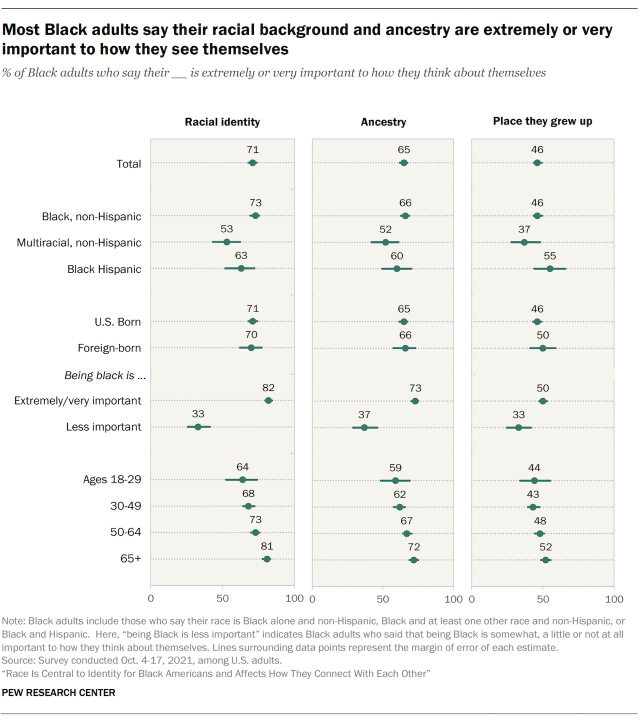

About seven-in-ten Black Americans (71%) say their racial background is very or extremely important to how they think of themselves, according to the survey. While U.S.-born (71%) and immigrant (70%) Black Americans are equally likely to hold this view, there are differences among Black adults of different racial backgrounds and ethnicities. About seven-in-ten (73%) of those who identify solely as Black say their racial background is very or extremely important to how they think of themselves. Meanwhile, smaller shares of Black adults who identify as multiracial (53%) say the same.

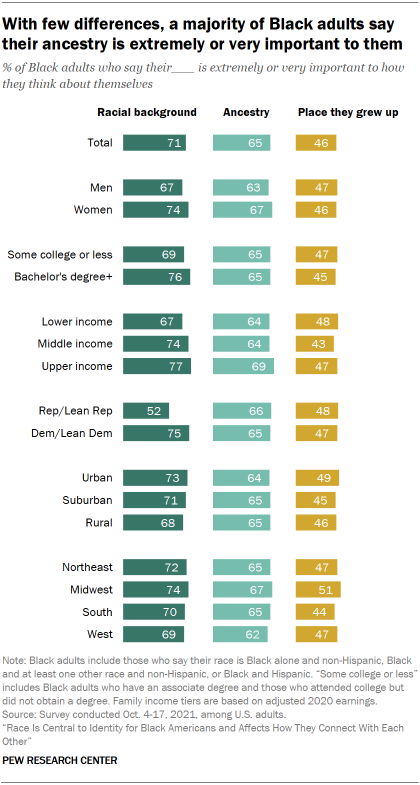

Gender, age, education, income and party are also key points of departure among Black adults when it comes to the importance of their racial backgrounds to their personal identity. Black women (74%) are more likely than Black men (67%) to say their race is an important part of how they think of themselves. When it comes to age groups, 81% of Black adults 65 and older say this, while 73% of those who are 50 to 64, 68% of those 30 to 49 and 64% of those under 30 say this.

There are also some differences by level of educational attainment. Black adults with at least a bachelor’s degree (76%) are more likely than those with lower levels of education (69%) to say that their racial identity is very or extremely important to them.

The importance of racial background to personal identity among Black Americans also differs by income.2 Black adults with middle incomes (74%) and those with upper incomes (77%) are more likely than those with lower incomes (67%) to share this view.

Black Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party (75%) are more likely than Black Republicans and Republican leaners (52%) to cite their racial identity as a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves.

The survey also finds about three-quarters (76%) of Black adults say specifically that being Black is important to how they see themselves. This is a view widely shared across most major demographic subgroups of Black Americans, as clear majorities of each say being Black is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves.

Ancestry and personal identity

Like racial identity and the importance of being Black, the majority (65%) of Black Americans say their ancestry is an important part of how they think about themselves.

While U.S.-born (65%) and foreign-born (66%) Black adults hold similar views on this question, non-Hispanic Black adults (66%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (52%) to say their ancestry is very or extremely important to their personal identity.

Black adults ages 65 and older (72%) are more likely than those who are 30 to 49 (62%) and slightly more likely than those under 30 (59%) to say that ancestry is very or extremely important to how they think about themselves. Meanwhile, the share of Black adults in the upper-income tier (69%) who hold this view is about the same as the shares of in the middle (64%) and lower tiers (64%). Looking at gender, nearly two-thirds of both Black women (67%) and Black men (63%) say that their ancestry is a very or extremely important part of their personal identity. There were no significant differences by education or by party affiliation among Black adults on this question.

The places where Black Americans grew up and personal identity

Black Americans were also asked how important the places where they grew up are to their personal identities. Nearly half of Black Americans (46%) say the location where they grew up is very or extremely important to how they think about themselves. Like racial identity and ancestry, this question differs somewhat for Black Americans of different ethnicities. Black Hispanic adults (55%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (37%) to say that where they grew up is very or extremely important to their identity. Similar shares of Black Americans who were born in (46%) or outside (50%) of the United States hold this view.

There are only slight regional differences in the share of Black adults who say where they grew up is very or extremely important to their personal identity. While 51% of Black Americans who live in the Midwest say this, 47% of those living in the Northeast or West and 44% of those who live in the South say this. Black adults who live in urban (49%), suburban (45%) or rural (46%) areas are also about as likely to say that where they grew up is very or extremely important to their personal identity.

Black Americans differ only slightly by age in views on the importance of where they grew up. Black adults who are 65 and older (52%) are more likely than those 30 to 49 (43%) to say that the location where they grew up is a very or extremely important part of how they view themselves.

The importance of gender and sexuality to personal identity

Gender and sexuality are also important components of how Black Americans think about themselves.

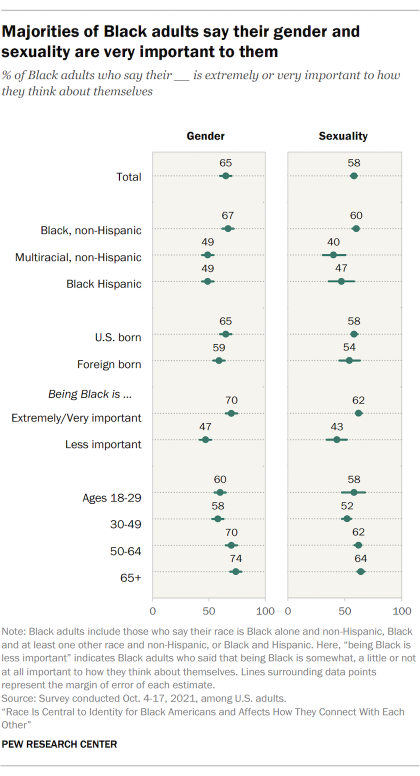

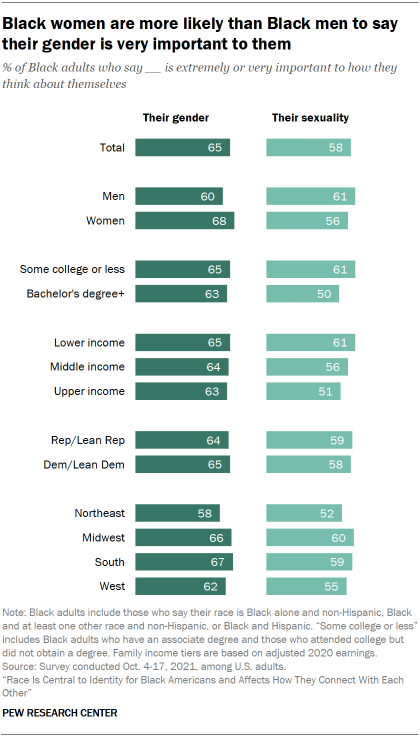

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Black adults say their gender is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves. Black women (68%) are more likely than Black men (60%) to say this, though clear majorities of each do.

Older Black Americans are more likely than younger ones to hold this view as well. Black adults who are 65 and older (74%) are more likely than those under 30 (60%) to say that their gender is a very or extremely important part of their identity.

Although there are no significant differences in the share who say this among U.S.-born (65%) or immigrant (59%) Black adults, there are differences by race and ethnicity. Non-Hispanic Black adults (67%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (49%) or Black Hispanic adults (49%) to say their gender plays a significant role in how they think about themselves.

Black adults who say that being Black is a very or extremely important part of how they think about themselves (70%) are much more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (47%) to say their gender is an important part of their personal identity.

Relatedly, nearly six-in-ten Black Americans (58%) say their sexuality is very or extremely important to them. The majority of Black men (61%) and Black women (56%) share this view. Meanwhile, Black adults 65 and older (64%) and 50 to 64 (62%) are more likely than those 30 to 49 (51%) to say their sexuality is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves.

Six-in-ten non-Hispanic Black adults say their sexuality is a very or extremely important part of how they think about themselves, while 40% of multiracial Black adults and 47% of Black Hispanic adults to say this. Much like their views on gender, Black adults who say that being Black is very or extremely important to them (62%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (43%) to say their sexuality is a significant part of their personal identity.

Black Americans who have at least a bachelor’s degree (50%) are less likely than those without one (61%) to say their sexuality is a very or extremely important part of how they think of themselves. And Black Americans with low incomes (61%) are more likely than those with higher incomes (51%) to hold this view.

Black Americans and connectedness to other Black people

Aside from questions about personal identity, Black Americans were asked about how much they have in common with different groups of Black people. They were also asked about how much what happens to other Black people in their local communities, in the United States and around the world affects what happens in their own lives.

Commonality with U.S.-born Black people

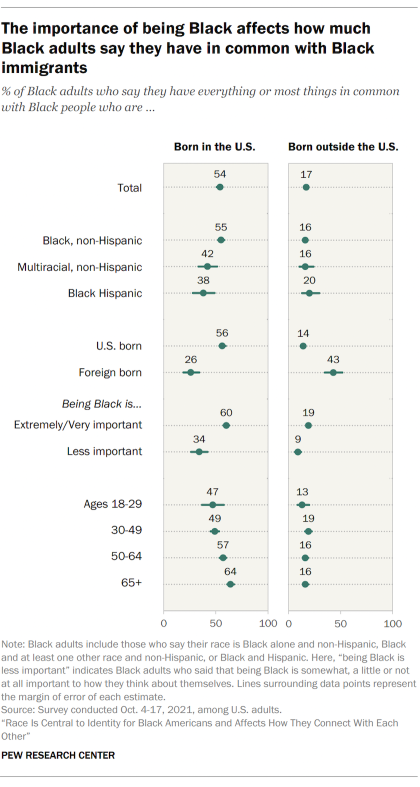

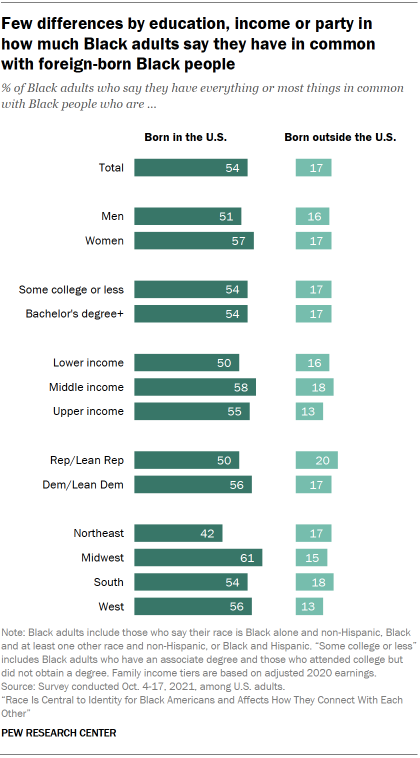

The majority of Black adults say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the United States (54%). U.S.-born Black adults are more likely than immigrant Black adults to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the U.S.3 Over half (56%) of U.S.-born Black adults say they have everything or most things in common with other Black people born in the U.S, with about a quarter (23%) saying they have everything in common.

Conversely, only about a quarter (26%) of Black adults who were born outside the U.S. say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the U.S.; 43% say they only have some things in common and 31% say they have few things or nothing in common in Black people born in the U.S.

More than half of non-Hispanic Black adults (55%) say they have all or most things in common with U.S.-born Black people, including 23% who say they have everything in common. A smaller share of multiracial Black adults (42%) say they have everything or most things in common with U.S.-born Black people.

Black adults who say being Black is very or extremely important to them (60%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (34%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people born in the United States.

Commonality with Black immigrants

Black Americans also shared how much they felt they had in common with Black people who were born outside of the United States, a group that makes up 12% of all Black Americans and is growing. The nation’s Black immigrant population is diverse, with just under half tracing their roots to the Caribbean and just under half to Africa.

Overall, just 17% of all Black adults say they have everything or most things in common with Black immigrants. Instead, a greater share said that they have some things in common with them (39%), rather than everything (5%) or most things (11%). In fact, about a quarter (24%) of all Black Americans say they have few things in common and 19% say they have nothing in common with Black immigrants.

Black immigrants (43%) are more likely than U.S.-born Black adults (14%) to say they have everything or most things in common with other Black immigrants. Meanwhile, 39% of U.S.-born Black adults say they have some things in common with Black immigrants, and nearly half (46%) say they have few things or nothing in common.

Black Americans also differ on this question along identity and ethnic lines. Black adults for whom being Black is a significant part of their identity (19%) are more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (9%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black immigrants. Meanwhile, nearly half of Black Hispanic adults (47%) say they have some things in common with Black immigrants. This is more than the shares of non-Hispanic (39%) or multiracial (32%) Black adults saying the same. In fact, non-Hispanic (43%) and multiracial (47%) Black Americans are most likely to say that they have few things or nothing in common with Black immigrants. According to the survey, Black Hispanic adults (29%) are significantly more likely than non-Hispanic (7%) and multiracial (5%) Black adults to be immigrants themselves.

Black Americans’ sense of commonality with Black immigrants differs somewhat based on region, education and income. Though there are no significant differences in the shares who say they have everything or most things in common with Black immigrants, Black adults from the Midwest (50%) are more likely than those from the Northeast (38%) or South (42%) to say they have few things or nothing in common with Black immigrants.

When it comes to education and income, nearly half of Black adults with a bachelor’s degree (46%) say they have some things in common with Black immigrants, compared with 36% of Black adults with lower levels of education. Meanwhile, the share of Black adults in the upper-income tier (50%) who hold this view is higher than those in the middle- (40%) and lower-income tiers (36%).

Commonality across social classes

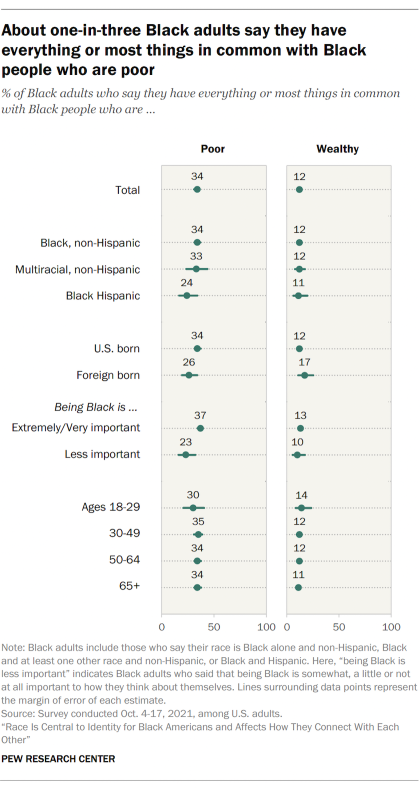

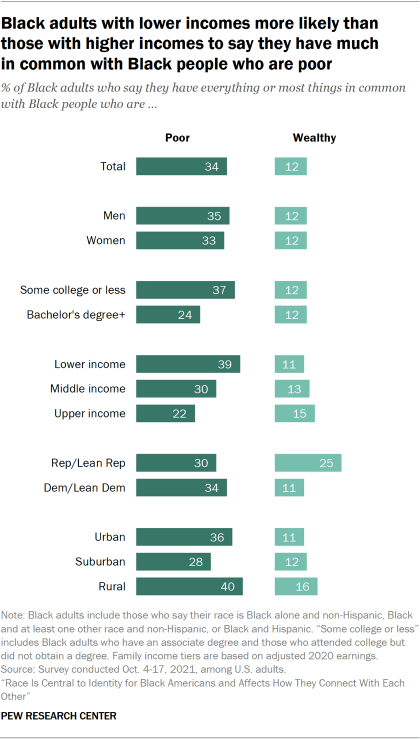

About one-in-three Black Americans say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor (34%). Another 43% of Black Americans say they have some things in common with Black people who are poor, while 22% say they have few things or nothing in common.

Nearly four-in-ten Black adults with lower incomes (39%) say that they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor, more than the share of middle (30%) or upper (22%) earners who say the same. However, about half of middle- (46%) and upper-income earners (51%) say they have at least some things in common with Black people who are poor.

Likewise, Black adults who earned a bachelor’s degree (24%) are less likely than those with lower levels of education (37%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor. But half of Black college graduates (51%) say they have some things in common.

Black Americans who live in rural (40%) and urban (36%) areas are more likely than those who live in the suburbs (28%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are poor. However, like the patterns above, about half of suburban Black people (47%) say they have some things in common.

When asked how much they have in common with Black people who are wealthy, few Black Americans say they have everything or most things in common (12%) with the group. Many more say they have some things in common (36%). However, half of Black Americans (50%) say they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy.

The shares of Black adults who say that they have few things or nothing in common with wealthy Black people vary based on education, income and community type. Only 12% of Black adults with or without a college degree say that they have much in common with Black people who are wealthy. Far more said the opposite. Black adults without a bachelor’s degree (53%) are more likely to say they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy than Black adults with at least a bachelor’s degree (42%).

Few Black Americans with lower (11%), middle (13%) or even upper (15%) incomes indicate they have everything or most things in common with Black people who are wealthy. Conversely, about six-in-ten Black lower-income earners (59%) say they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy. This makes them more likely than Black middle- (46%) and upper-income earners (32%) to say the same. Finally, Black adults who live in urban areas (54%) are more likely than those living in rural (46%) or suburban (48%) areas to say that they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who are wealthy.

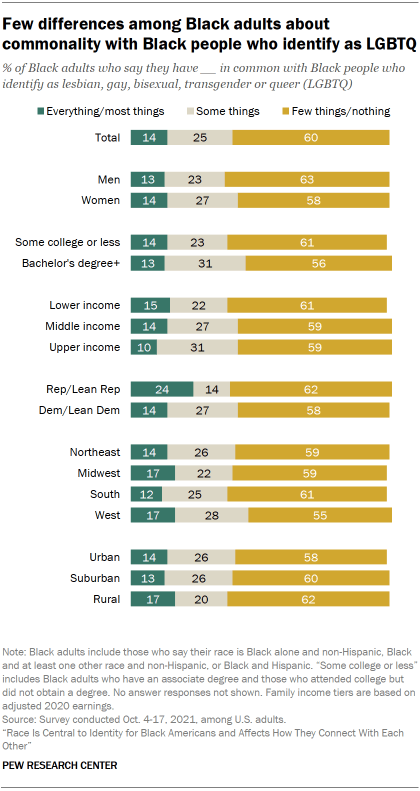

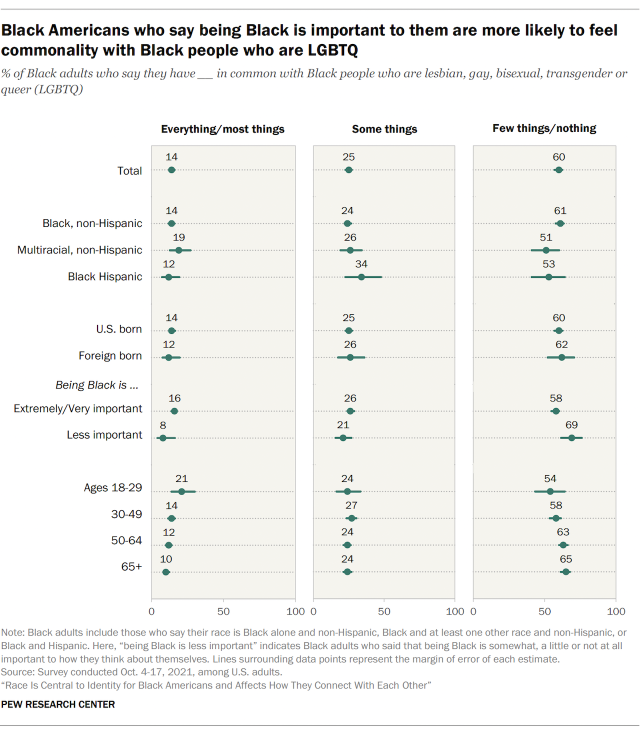

Commonality with LGBTQ Black Americans

A small share (14%) of Black Americans say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ). The majority of Black Americans say they have few things or nothing in common (60%) with LGBTQ Black people.

Black Americans’ sense of commonality with Black people who have LGBTQ identities vary by age, gender, ethnicity, education, income and party. Black adults who are under 30 (21%) and those ages 30 to 49 (14%) are more likely than those 65 and older (10%) to say they have everything or most things in common with Black people who have LGBTQ identities.

Conversely, Black adults who are 50 to 64 (63%) and 65 and older (65%) are more likely than those who are 30 to 49 (58%) to say that they have few things or nothing in common with Black people who identify as LGBTQ.

Equal shares of Black men (13%) and women (14%) say they have all or most things in common with Black people who identify as LGBTQ. However, Black men (42%) are more likely than Black women (34%) to say they have nothing in common. Small shares of non-Hispanic Black adults (14%), multiracial Black adults (19%), and Black Hispanic adults (12%) say they have all or most things in common with Black people who are LGBTQ. However, non-Hispanic Black adults (38%) are more likely than Black Hispanic adults (26%) to say that they have nothing in common.

Four-in-ten Black adults who have not attained a bachelor’s degree (40%) say that they have nothing in common with Black people who are LGBTQ, compared with 28% of Black college graduates. Similarly, Black adults in the lower-income tier (40%) are more likely than those in the upper-income tier (31%) to hold this view. Among Black Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party, 44% say they have nothing in common with Black people who have LGBTQ identities – higher than the share of Black Democrats and leaners (35%) who say the same.

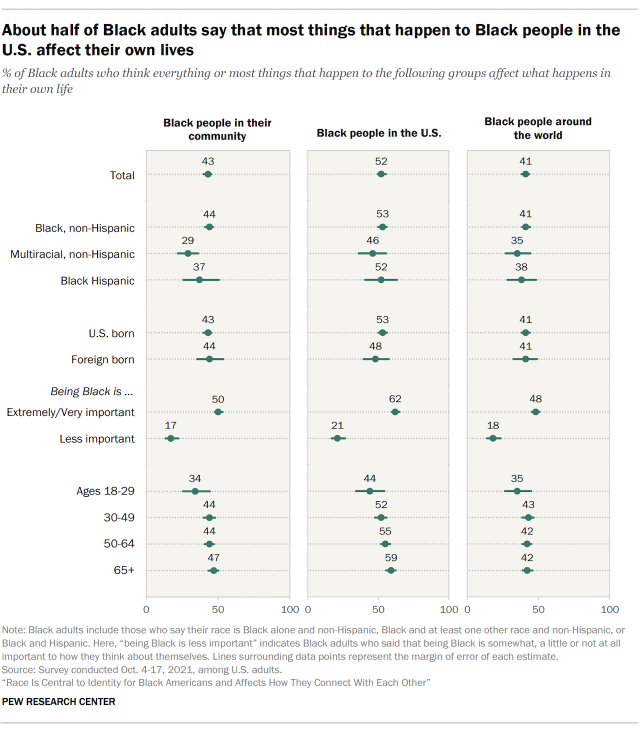

Intra-racial connections locally, nationally and globally

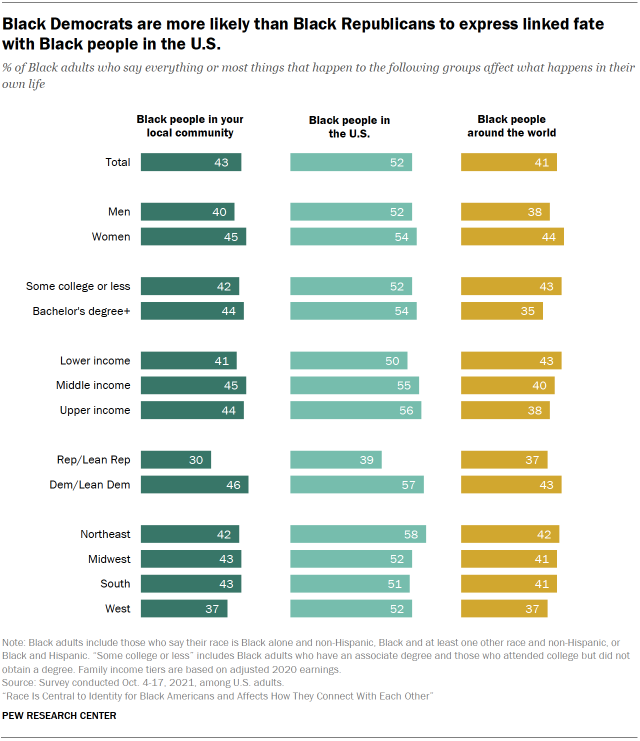

While many Black adults feel a sense of connection and common fate with other Black people, nearly as many do not. Overall, they were most likely to say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in the United States (52%), rather than those in their local communities (43%) or around the world (41%), affect what happens in their own lives.

Local intra-racial connections

Similar patterns hold when Black Americans were asked about how connected they felt to Black people in their local communities. Non-Hispanic Black adults (44%) are more likely than multiracial Black adults (29%) to say that what happens to Black people in their local communities affects what happens in their own lives. And Black adults who say that being Black is a very or extremely important part of their identity (50%) are far more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (17%) to hold this view.

U.S.-born (43%) and immigrant (44%) Black adults are about as likely to say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local areas impact their own lives. Black adults also do not differ by community type on this question. Those who live in urban (42%), suburban (41%) or rural (47%) areas are equally likely to say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local communities affect their lives.

While nearly half of Black Americans ages 30 to 49 (44%), 50 to 64 (44%) and 65 and older (47%) say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in their communities impact them, Black young adults (34%) stand apart as being less likely than those 65 and older to say this. In fact, Black adults under 30 are more likely than all other age groups to say few things or nothing that happens to Black people in their local communities impacts their own lives. When it comes to education and income, Black Americans’ views on this question are mixed. While 44% of Black college graduates say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local communities impact their own lives, a similar share (42%) say that only some things affect them. Among Black adults without a college degree, 42% say everything or most things that happen to Black people in their communities affect them, and 32% say only some things would affect them.

About four-in-ten Black Americans across income groups say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local communities affect them. However, Black people in the middle- and upper-income tiers also say that some things affect them (37% and 41%, respectively), while 31% of those with lower incomes say this.

Black Americans differ by party on this question, with Black Democrats and Democratic leaners (46%) being more likely than Black Republicans and Republican leaners (30%) to say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in their local communities affect them.

National intra-racial connections

U.S.-born Black adults (53%) are no more likely than Black immigrants (48%) to say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in the United States affect what happens in their own lives. When it comes to ethnicity, non-Hispanic Black adults (53%), Black Hispanic adults (52%) and multiracial Black adults (46% ) are all about as likely to say that everything or most things that happen to Black people in the U.S. affect them. However, Black Americans who say being Black is a very or extremely important of their personal identity (62%) are far more likely than those for whom being Black is less important (21%) to say that what happens to other Black people in the U.S. affects them. Black adults who are 50 to 64 (55%) or 65 and older (59%) are more likely to hold this view than those under 30 (44%). Black adults under 30 are also more likely than any other age group to say that a few things or nothing that happens to Black people in the U.S. affects what happens in their own lives.

Black Americans also differ on this question by party. Black Democrats (59%) are more likely than Black Republicans (39%) to say everything or most things that happen to Black people in the United States would impact their own lives.

There are few differences among Black Americans on this question by gender and education. About half of Black men (52%), Black women (54%), Black college graduates (54%) and those with lower levels of education (52%) say everything or most things that happen to Black people in the U.S. affect them personally. Likewise, there are few differences by income, with around half of Black adults who are in the low- (50%), middle- (55%) and upper-income tiers (56%) sharing this view.

Global intra-racial connections

Finally, Black Americans were asked about how connected they felt to Black people around the world. About four-in-ten (41%) say everything or most things that happen to these Black people impact their own lives. Immigrant (41%) and U.S.-born (41%) Black adults are about as likely to hold this view. So are non-Hispanic (41%), multiracial (35%) and Hispanic (38%) Black adults. However, Black adults who say that being Black is very or extremely important to them (48%) are more than twice as likely as those for whom being Black is less important (18%) to say what happens to Black people around the world affects what happens in their own lives.

Black women (44%) are slightly more likely than Black men (38%) to say what happens to Black people around the world affects their own lives. There are few significant age differences, with nearly 40% of all age groups sharing this view. However, much like their views on Black people in the U.S. and in their local communities, Black adults under 30 are more likely than older age groups to say that few things or nothing that happens to Black people around the world impacts them.

Black adults differ by education and income on this question. Those with less than a bachelor’s degree were more likely than those with a bachelor’s degree or higher level of education to say that everything or most things that happen to Black people around the world affects them (43% vs. 35%). Black adults across income tiers were about as likely to share this view, with about 40% of each group saying so. Black adults differ by party in the share who say that a few things or nothing that happens to Black people around the world affects what happens in their lives. Black Democrats and Democratic leaners (19%) were less likely to say this than Black Republicans and GOP leaners (39%).