Satisfaction with nation’s direction at highest level in a decade as most say the worst of the pandemic is behind us

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand the financial and personal impact of the coronavirus pandemic on the nation’s Hispanic population, one year after it began. The study also explores the views of Hispanics about the situation of their group in the United States today.

For this analysis we surveyed 3,375 U.S. Hispanic adults in March 2021. This includes 1,900 Hispanic adults on Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 1,475 Hispanic adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel. Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. Recruiting panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling), or in this case the whole U.S. Hispanic population.

To further ensure the survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation’s Hispanic adults, the data is weighted to match the U.S. Hispanic adult population by age, gender, education, nativity, Hispanic origin group and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for our survey of Hispanic adults, along with responses, and its methodology.

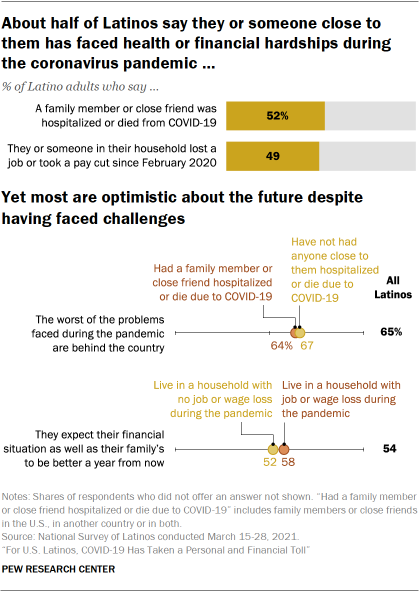

More than a year into the pandemic, Latinos in the United States say COVID-19 has harmed them and their loved ones in many ways. About half say a family member or close friend has been hospitalized or died from the coronavirus, and a similar share say they or someone in their household has lost a job or taken a pay cut during the pandemic. Yet amid these hardships, Latinos are upbeat about the future. Nearly two-thirds say the worst of the coronavirus outbreak is behind the country, and a majority say they expect their financial situation and that of their family to improve over the next year.

Job and wage losses in Latino households during the pandemic were just as likely for those born in another country as those born in the U.S., according to a bilingual, online survey of 3,375 U.S. Latino adults conducted in March 2021. However, among immigrant Latinos, some groups were harder hit than others – a relatively high share (58%) of Latino immigrants without U.S. citizenship and without a green card say they or someone in their household has lost a job or wages since February 2020, compared with 45% of naturalized U.S. citizen immigrants who say this.1

Yet Latinos see better days ahead for themselves and the country, even if they have experienced hardship due to COVID-19. Most Latinos say they think the worst of the problems the country is facing from the outbreak are behind us, with similar majorities saying so among those who have had and not had someone close to them hospitalized or die due to the coronavirus. In addition, a slight majority of Latinos (54%) say they expect their personal financial situation will be better a year from now, with only modest differences between those in households that have and have not experienced a loss of jobs or wages since the start of the pandemic.

The terms Hispanic and Latino are used interchangeably in this report.

Unless otherwise indicated, the term U.S. born refers to people who are U.S. citizens at birth, including people born in the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories, as well as those born elsewhere to at least one parent who is a U.S. citizen.

Unless otherwise indicated, the term foreign born refers to persons born outside of the United States to parents neither of whom was a U.S. citizen. The terms foreign born and immigrant are used interchangeably in this report.

Second generation refers to people born in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories with at least one first-generation, or immigrant, parent.

Third or higher generation refers to people born in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories with both parents born in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.

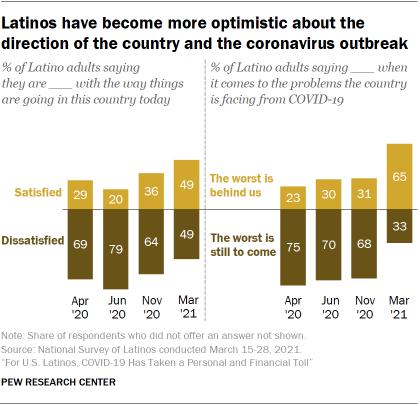

Over the course of the pandemic, Latinos have become more optimistic about the country. About half (49%) say they are satisfied with the nation’s direction, up from June 2020, when 20% said the same. This is the most satisfied Latinos have been with the nation’s direction since 2012, when 51% said so. At the same time, the share saying the worst of the pandemic is behind us as a nation is up sharply, from 23% in April 2020 to 65% in March 2021. Meanwhile, Latino adults are more likely today than before the pandemic to say the situation of U.S. Latinos has improved or stayed about the same over the past year, and they are less likely to say the situation of Latinos has worsened.

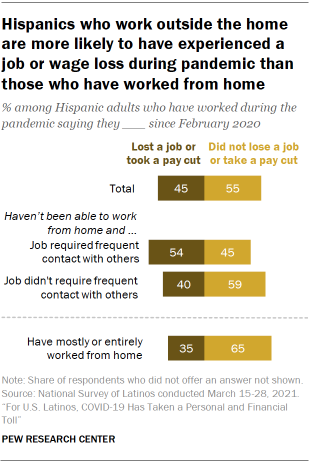

Hispanics have been at a higher risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 than some other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S., according to data compiled by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC reports this data in part because race and ethnicity can be a marker for risk factors such as lack of access to health care and exposure to the coronavirus from jobs that require frequent contact with others. According to the new Pew Research Center survey, 45% of Hispanic adults have worked at jobs that required them to work outside the home since February 2020.

At the same time, Hispanics have been more vulnerable to economic hardship during the pandemic than some other groups, again in part because of the jobs they hold. About half of Hispanics (54%) who have worked outside their home during the pandemic in a job that involves frequent contact with others say they have experienced a job or wage loss since the start of the pandemic, a higher share than among those who work mostly or entirely at home (35%).2

Latinos and financial hardships during the pandemic

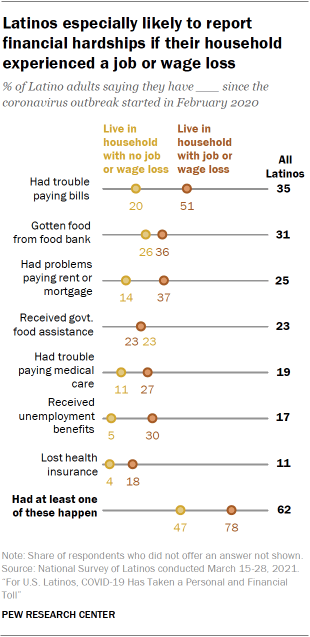

About six-in-ten (62%) say they have experienced at least one of seven financial hardships asked about in the survey, with Latinos most often saying they have had trouble paying bills (35%) and gotten food from a food bank or other charitable organization (31%).

Hispanics living in households where someone has lost a job or wages since February 2020 are more likely to say they have experienced financial challenges during the pandemic than other Hispanics. More than three-quarters (78%) of Hispanics living in these households say they experienced at least one of the seven hardships asked about in the survey. Even among households where no one has lost a job or wages during the pandemic, nearly half (47%) say they have experienced one of these hardships.

Hispanics living in households where someone has lost a job or wages are more than twice as likely to say they have had trouble paying bills than those in households without a job or wage loss (51% vs. 20%). Being able to afford housing has also proven difficult for some – 37% of Hispanics in households with a job or wage loss say they have had trouble paying their rent or mortgage since February 2020, compared with only 14% of households that have not experienced a job or wage loss.

The survey also finds that financial struggles can vary among Latino immigrants depending on their legal status. About half (48%) of Latino immigrants without a green card have had a hard time paying their bills during the pandemic, a higher share than among those with a green card (35%) or those who are naturalized U.S. citizens (26%). By comparison, about one-third (35%) of U.S.-born Latinos have had trouble paying their bills since February 2020.

A lower share of U.S. adults than Hispanics in August 2020 said they had experienced financial hardships during the pandemic. Trouble paying bills (25%), the need to get food from a food bank or charitable organization (17%) and trouble paying rent or mortgage (16%) were among the challenges reported among U.S. adults.

During the worst of COVID-19, Hispanics extended a helping hand to family and friends

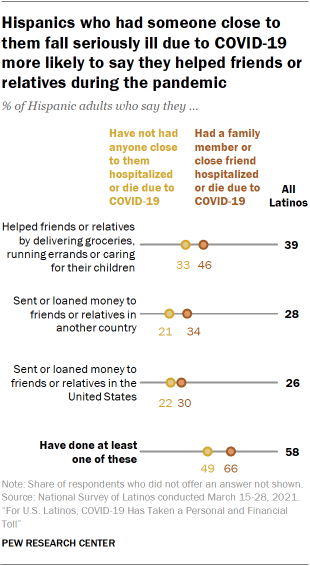

Amid these challenges, Hispanics have leaned into family ties and friendships during the pandemic. A majority (58%) say they have helped relatives or close friends in several ways – by delivering groceries, running errands or caring for their children (39%), sending or loaning money to family or friends in another country (28%), or sending or loaning money to family or friends in the U.S. (26%).3

The survey also shows a link between helping family and friends and having someone close fall ill with COVID-19. Two-thirds (66%) of Hispanics who say they have had someone close to them fall seriously ill due to COVID-19 also say they have helped a family member or close friend in one of these ways. By comparison, a lower but still substantial share (49%) of Hispanics who have not had someone close to them get seriously ill helped family or friends. Differences between these groups extend to those who have helped friends or relatives with groceries, errands or child care (46% vs. 33%), sent or loaned money to friends or relatives in another country (34% vs. 21%) and sent or loaned money to friends or relatives in the U.S. (30% vs. 22%).

Hispanic parents have struggled with child care during the pandemic

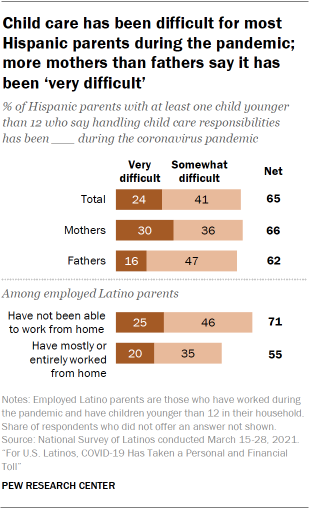

Hispanic parents report experiencing challenges of their own during the pandemic. About two-thirds (65%) of Hispanic parents with at least one child younger than 12 living in their home say handling child care responsibilities has been somewhat (41%) or very (24%) difficult during the outbreak. Among Hispanic parents, mothers are more likely than fathers to say handling child care responsibilities has been very difficult (30% vs. 16%).

Employed Hispanic parents with children younger than 12 who have not been able to work from home during the pandemic are more likely to say they have found child care very or somewhat difficult than those who have been able to work from home (71% vs. 55%). Overall, two-thirds (67%) of employed Hispanic parents who worked during the pandemic and have children younger than 12 in their home have had trouble handling child care responsibilities.

Latino parents are also concerned that the pandemic has disrupted their children’s progress in school. Three-in-four Latino parents of K-12 students (76%) say they are somewhat (33%) or very (42%) concerned that their children have fallen behind in school due to disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak. Parents have similar levels of concern whether their children have received online-only instruction or have had a mix of in-person and online instruction. About three-quarters of each say they are somewhat or very concerned their child has fallen behind.4

By comparison, about half (52%) of all U.S. working parents with children younger than 12 said it has been very or somewhat difficult to handle child care responsibilities in October 2020. In addition, about two-thirds (65%) of U.S. parents of K-12 students said they are very or somewhat concerned about their children falling behind in school due to the outbreak.